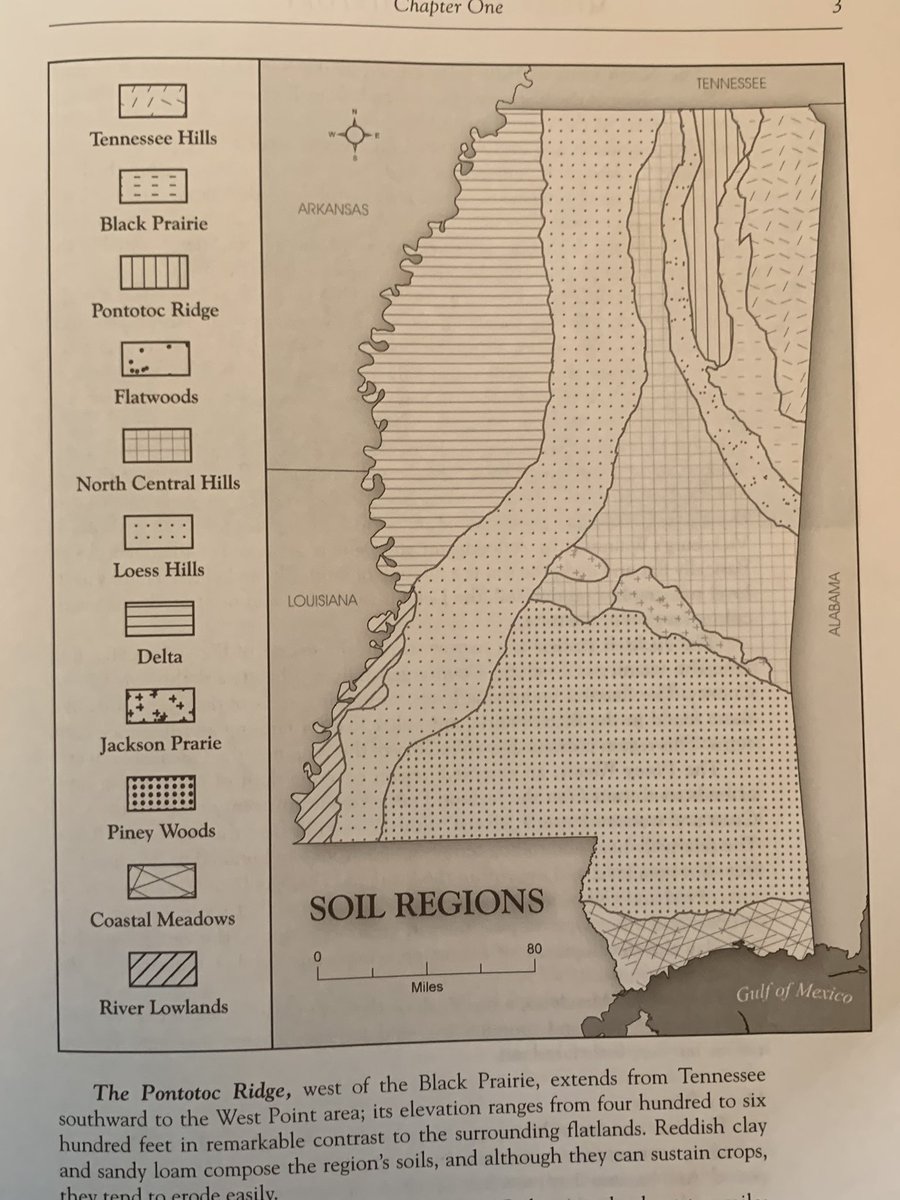

What I love about maps like these is how much the social history of a state like Mississippi is influenced by soil differences that most people today barely recognize. Sure, everybody knows the Yazoo Delta and Piney Woods. Or maybe that the “Black Prairie” goes into Alabama.

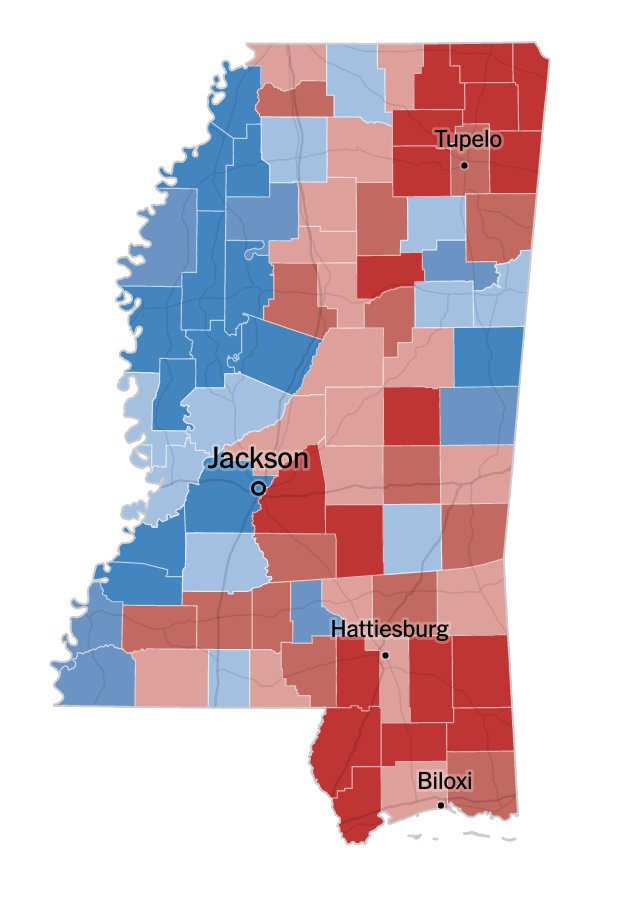

But when you dial in to the more subtle soil differences between, say, the Jackson Prairie, North Central Hills, and Loess Hills, you can start to see some of the local level agricultural and social history at work. And demographic history too.

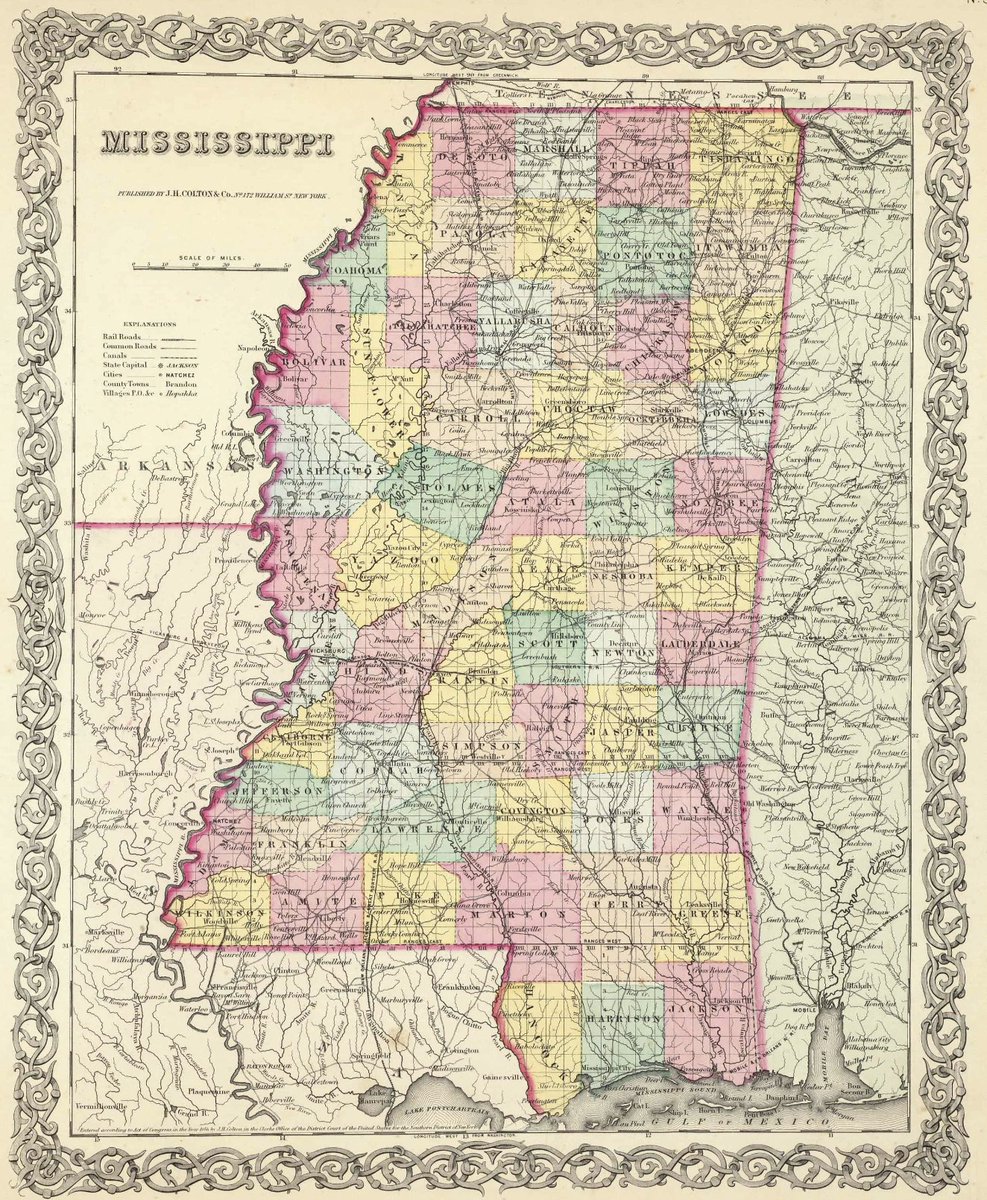

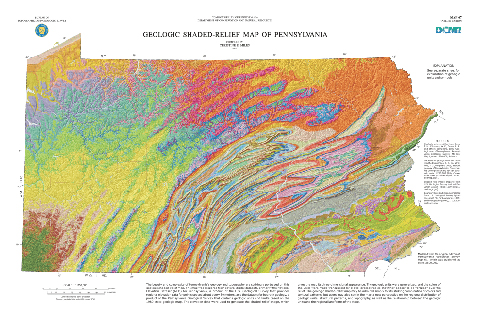

Here& #39;s an 1856 map of Mississippi. The various hills in the state are so low that transportation barriers were quite low. Unlike Pennsylvania or Virginia where the challenge of crossing multiple ridges showed up in early turnpike and railroad maps.

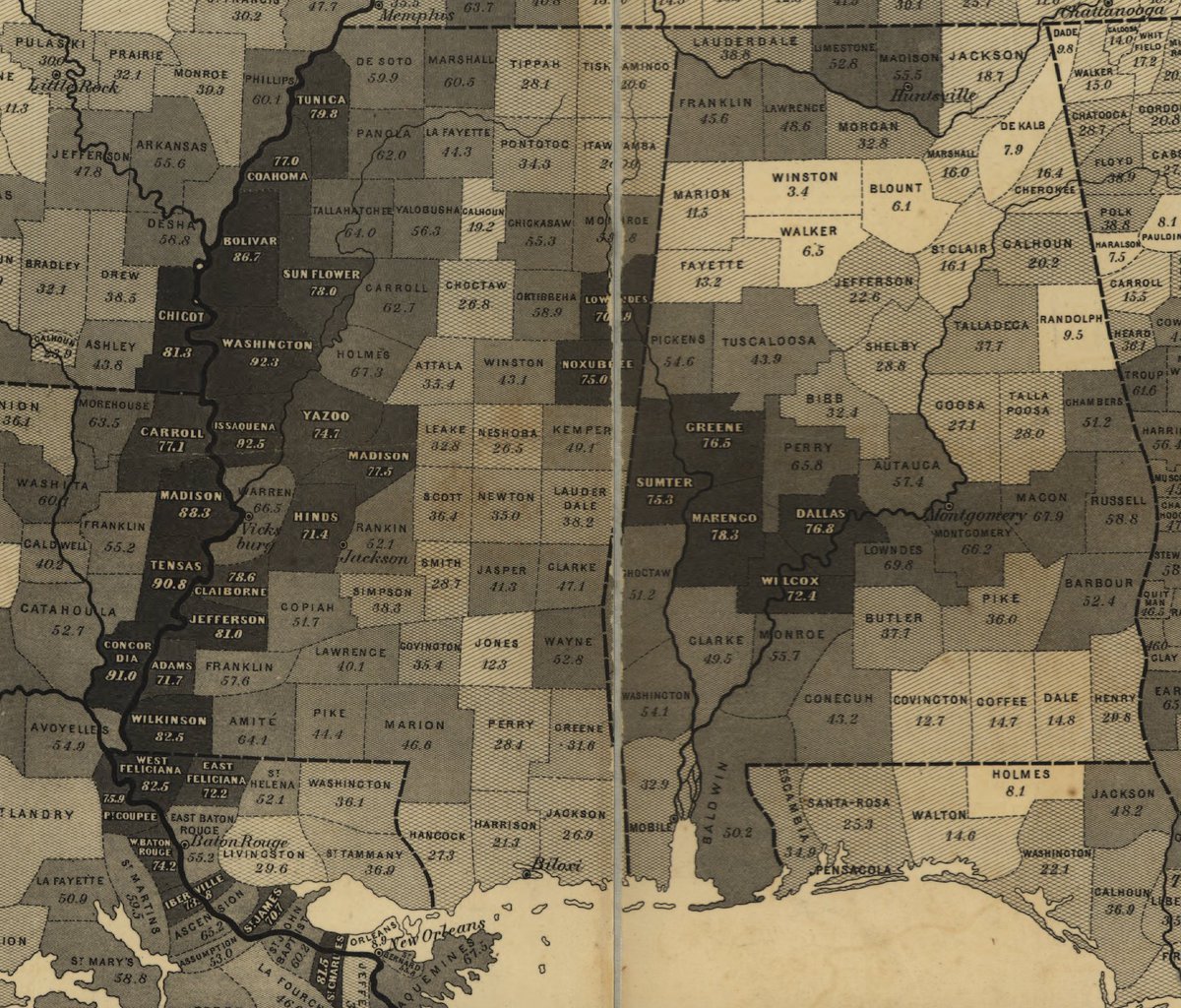

This map of slavery from 1860 shows the importance of soil differences better than the 1856 political/transportation map. The "Black Prairie" in eastern Mississippi clearly dips down into central Alabama. Also see differences between Madison and Leake or Attala Counties.

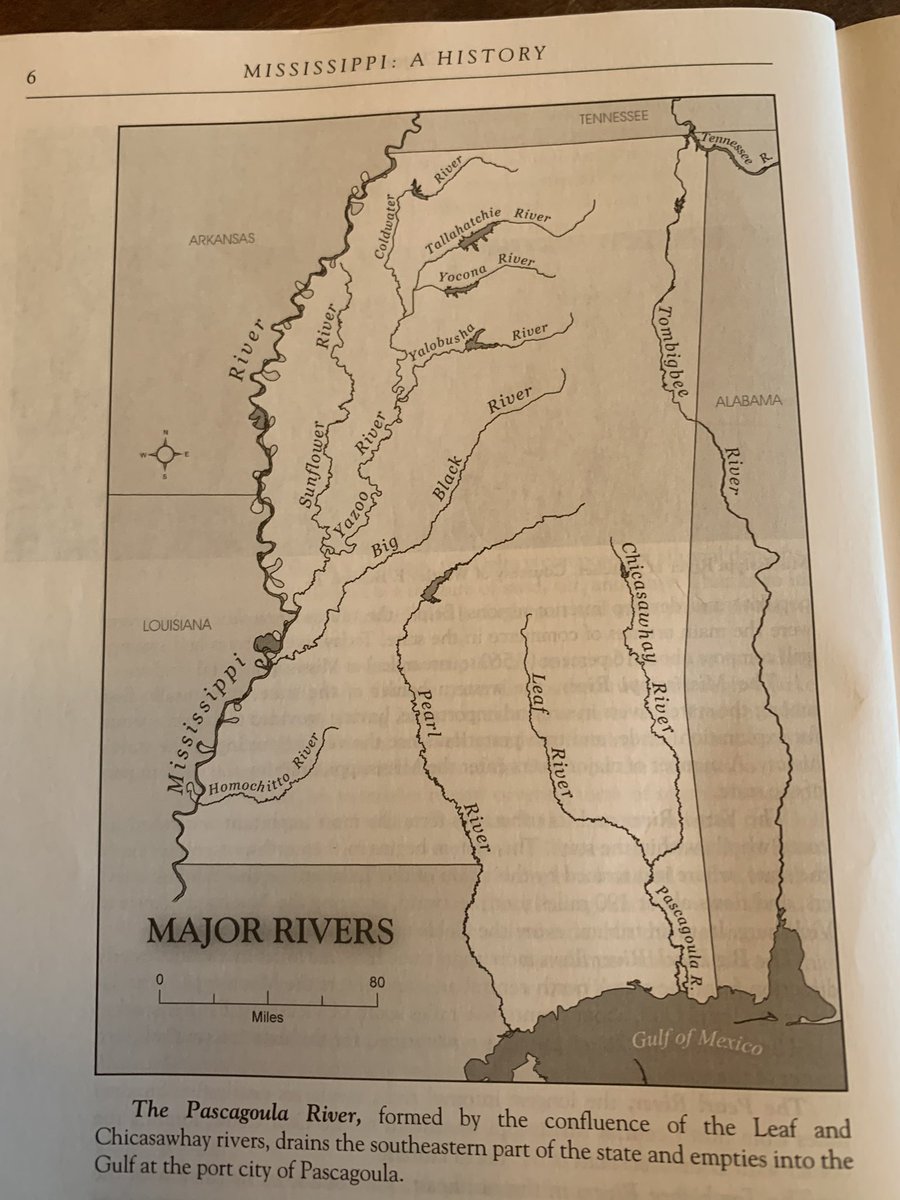

River maps also help explain agricultural development, as well the location of market towns and cities. There was no faster way to travel in the early 19th century than by water. Note where the Pearl and Black Rivers nearly join together. Madison County is between them.

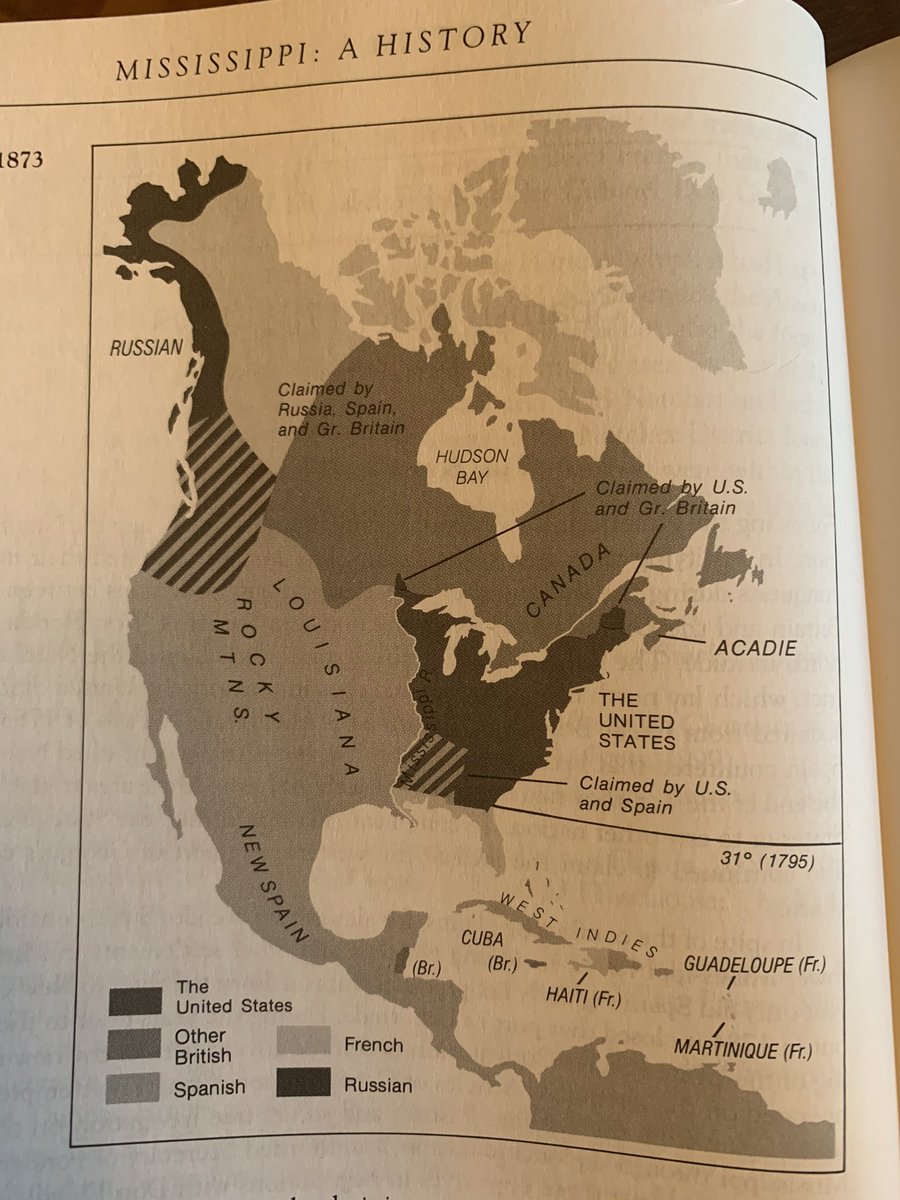

But the land doesn’t determine everything. Geopolitics turned places like late 18th/early 19th c Mississippi into zones of competing and often overlapping colonial zones, giving us oddities like “West Florida.”

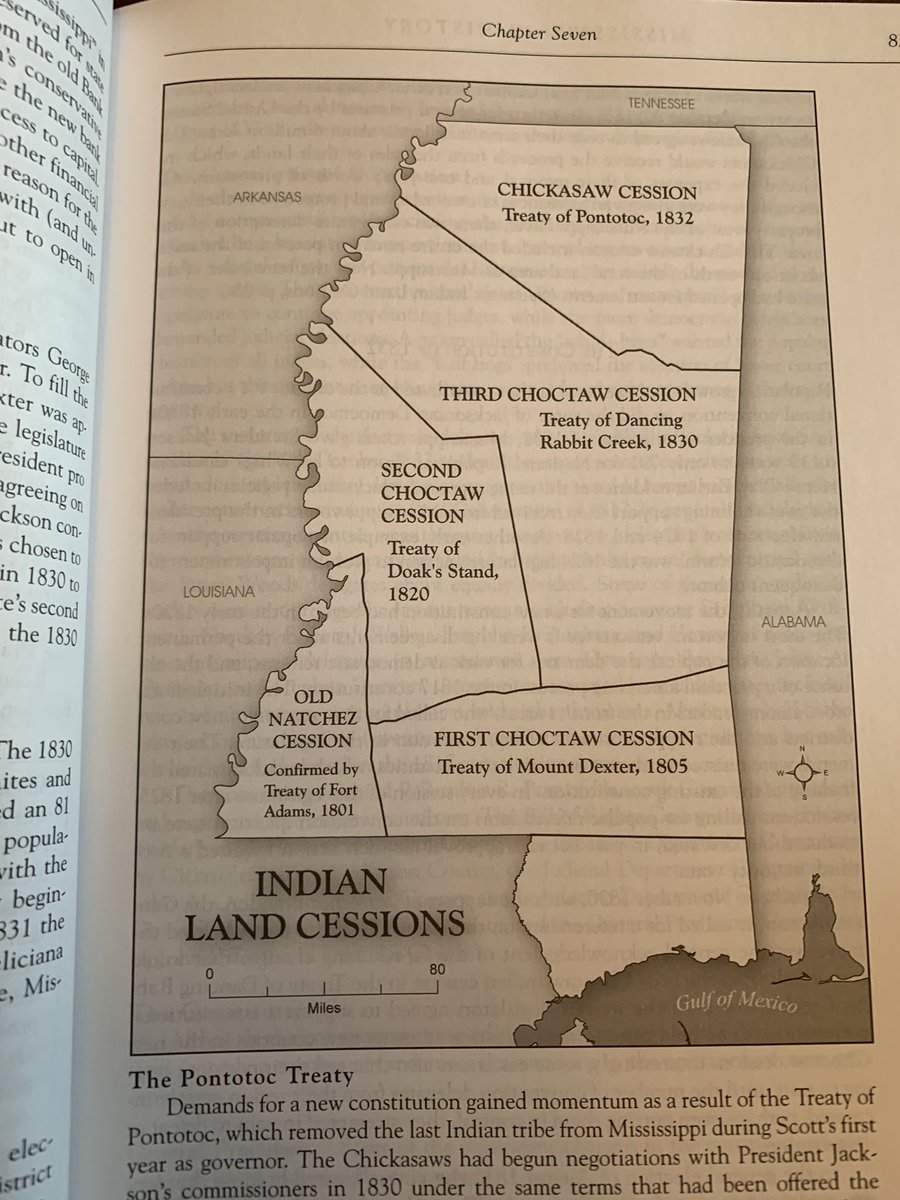

The Jacksonian-era politics of “Indian Removal” contributed to the timing of some sub-regions’ agricultural development. The 10-year difference between the Doak’s Stand and Dancing Rabbit Creek treaties affected the politics of central Mississippi quite a bit.

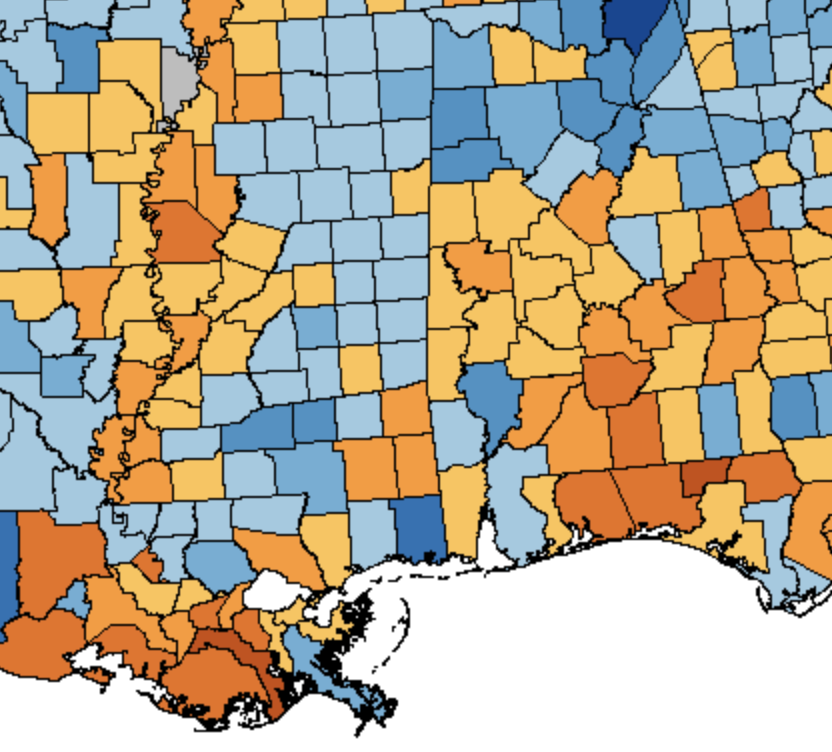

The Second Party System (Democrats v. Whigs, 1830s to 1850s) also reflected some of this timing. In the 1848 election, the orange (Whig) counties were general some of the "older" counties from the first Choctaw cessions. Blue (Democratic) counties the "newer" ones.

But the soil map helps explain southern Mississippi politics better than the "Indian Cessions" map. Jacksonian Democrats were strongest not just in the "newer" east but also in the more hardscrabble Piney Woods of the south/southeast part of the state.

We rarely think about this stuff today except in brief grade school "state history" classes. But the enduring power of these soil/agricultural patterns - and the demographic result - is profound. This is a map of the 2018 special election between Espy and Hyde-Smith.

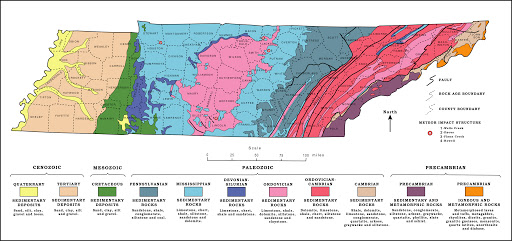

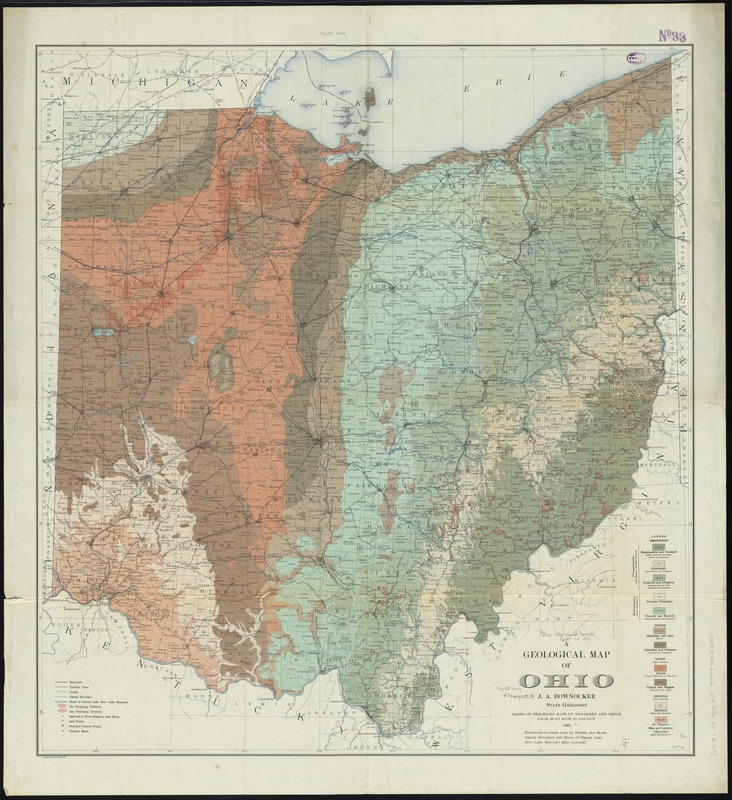

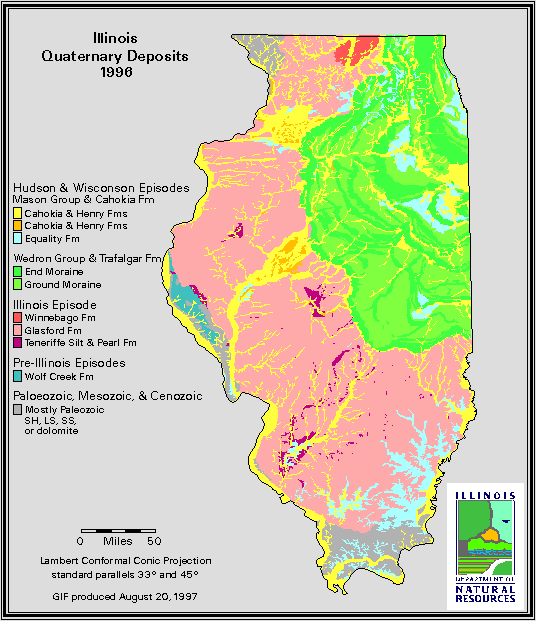

You can see the effect of geology and soil more starkly in states with variegated terrain like PA, TN or OH (esp. SE OH). But also in topographically homogenous states like Illinois.

Few of us live off the land anymore, or make a living from timber, mining or agricultural trade. We "see" these land differences on car trips from city to city. But the natural sub-strata of 21st century social and political life is still there if we look for it.

It& #39;s also true, as William Cronon points in "Nature& #39;s Metropolis" (about Chicago and the Midwest) that much of today& #39;s rural landscape is every bit as "man-made" as the urban. The forests and prairies gave way to cultivated corn, cotton and soybean fields.

These agricultural/rural changes had profound effect on growth of nearby market cities in neighboring states (Memphis and New Orleans for Mississippi). The urban and rural have always been economically co-dependent, even if often culturally antagonistic.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter