As Irish Americans, we can’t celebrate our heritage without first coming to terms with the fact that our identity is constructed on a foundation of anti-Blackness. A thread about that history for #StPatricksDay:

In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Irish immigration to the US was reaching its peak with nearly two million Irish arriving between 1820 and 1860.

In the Northern states, Irish immigrants and an increasing number of free Blacks found themselves competing for the same low rung on the social ladder, and for the same jobs.

Irish Catholics were the undesirable immigrant group of that era. And in a system where assigned racial identities had as much to do with national origin as skin color, the Irish occupied a social category closer to Black than White.

In order to improve their status in their adopted homeland, the Irish had to work to achieve Whiteness and its attendant privileges.

Historian Noel Ignatiev shows how the Irish established this desired Whiteness by deliberately differentiating themselves from Black people by — at times violently — forcing them into an even lower ranking in the American social order.

This played out across many social spheres, including competition in the labor sector: In the antebellum period, Irish often found themselves competing with free Blacks for the same jobs in the Northern states.

Under the direction of Irish Catholic clergy they began systematically offering to work for less than Black laborers.

In 1860 a Catholic priest in Philadelphia told his congregants, “you must do everything that [Black workers] do, no matter how degrading, and do it for less than they can afford to do it for.”

Thanks to this strategy, factories and artisanal trades become predominantly fueled by Irish labor. The Irish then used their numbers to threaten strikes and riots if even a single Black worker was brought on to the job.

If they worked better jobs for better pay, the logic went, they would prove themselves worthy of a higher racial and social class.

In 1853 Frederick Douglass wrote that “every hour sees us elbowed out of some employment to make room for some newly-arrived emigrant from the Emerald Isle, whose hunger and color entitle him to special favor.”

Douglass went on to say: “If they cannot rise to the dignity of white men, they show that they can fall to the degradation of Black men. In assuming our avocation the Irishman has also assumed our degradation.”

Even the burgeoning worker rights movement failed to see slavery as a labor issue. On the contrary, Irish American workers compared their condition unfavorably to slavery.

Self-identifying as “wage slaves,” they claimed they had it far worse than actual slaves because they weren’t entitled to “benefits” like the material comfort and assurance of work they perceived slaves as enjoying.

As a Congressman at the time claimed, the only difference between slaves in the South and wage slaves in the North was that “The one is the slave of an individual; the other is the slave of an inexorable class.”

Frederick Douglass famously reminded such detractors that his former job on the plantation was still vacant, should any dare to test the veracity of this false equivalency.

And believing that the end of slavery would ultimately lead to more competition for jobs and depressed wages, Irish Americans took a strong stance against the abolition movement.

They also protested violently against the Civil War draft. In the aftermath of the war, Irish American anti-Blackness was pervasive, as illustrated by cartoons like this: http://content.mpl.org/cdm/ref/collection/MHTCC/id/44">https://content.mpl.org/cdm/ref/c...

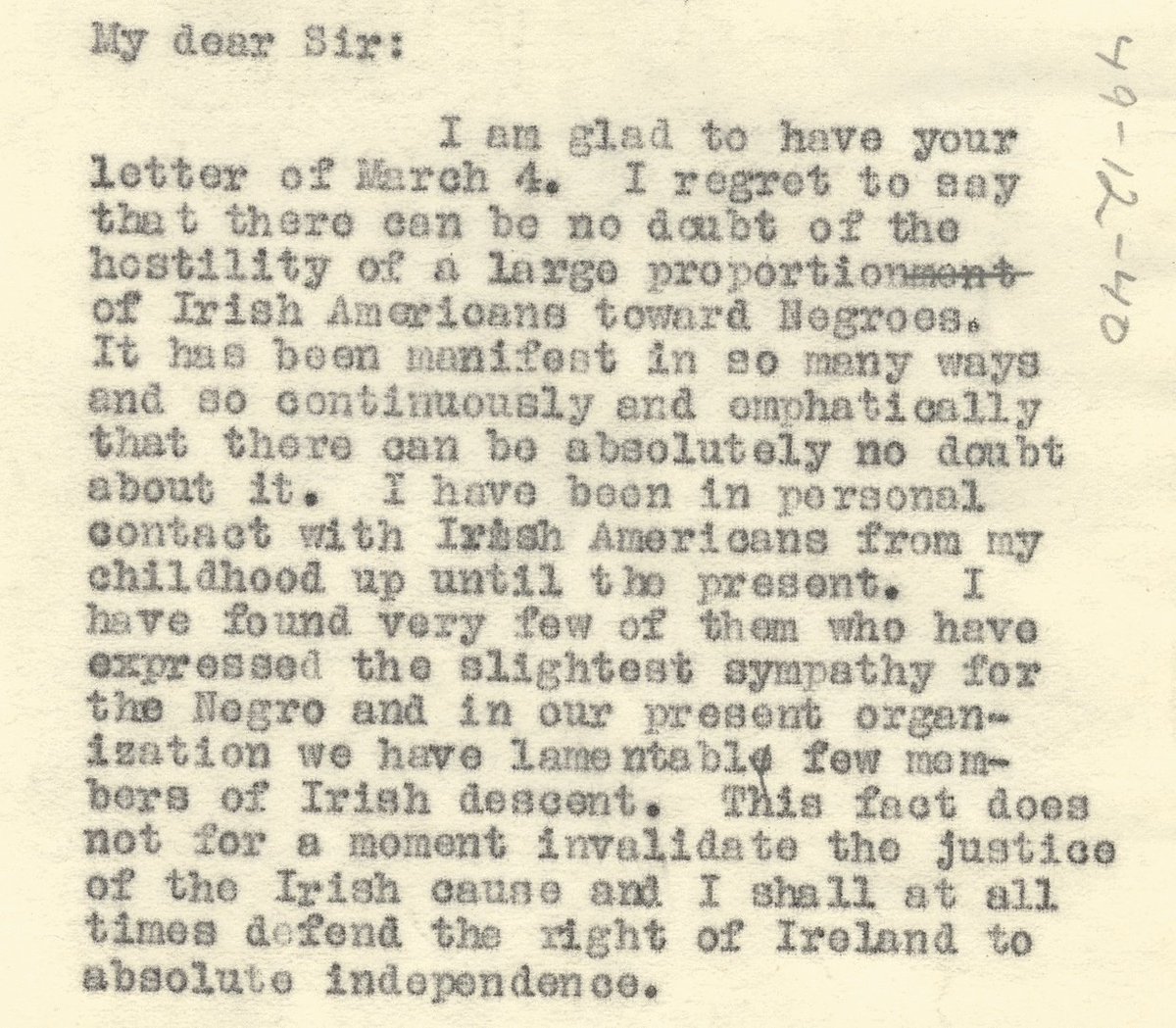

In 1919 W.E.B. DuBois wrote, “I must say frankly that there are some sinister anti-Negro influence in the American Church largely among Irishmen, who oppose the just treatment of Negroes.” http://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b015-i208">https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full...

Later, DuBois wrote that Irish American anti-Blackness has “been manifest in so many ways and so continuously and emphatically that there can be absolutely no doubt about it.” http://bit.ly/2FYuaAV ">https://bit.ly/2FYuaAV&q...

Today, Irish Americans invoke a bootstrap narrative that celebrates the fact that we pulled ourselves up from destitution and made it in America. But if there is any truth that narrative we have to acknowledge that those boots rest on a foundation of anti-Blackness.

Instead, the bootstrap narrative is used as “evidence” to further racist notions of Irish American/white superiority. This facebook comment illustrates exactly how this twisted logic is often employed:

The current “Irish slave” myth, which has been thoroughly debunked by historian Liam Hogan @Limerick1914 and others is just the latest iteration in this long history of anti-Blackness. I wrote about it here for @PRI @globalnation: https://www.pri.org/stories/2017-03-17/curious-origins-irish-slaves-myth">https://www.pri.org/stories/2...

Liam Hogan now estimates that "tens of millions of people have been exposed to ‘Irish slaves’ disinformation in one form or another on social media.” https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Society/2018/0316/No-the-Irish-were-not-slaves-in-the-Americas">https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Socie...

This #StPatricksDay let’s celebrate by committing to learn this history. Read Noel Ignatiev’s “How the Irish Became White,” from which I drew some of the content and arguments in this thread: https://www.amazon.com/Irish-Became-White-Routledge-Classics/dp/0415963095">https://www.amazon.com/Irish-Bec...

Talk to your families about the “Irish slave” myth and why it’s wrong, follow @LiamHogan, read his work: https://medium.com/@Limerick1914/the-imagery-of-the-irish-slaves-myth-dissected-143e70aa6e74#.xhxaucbu2">https://medium.com/@Limerick...

Finally, let’s talk frankly and honestly about the debt we owe African Americans given this history. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/06/magazine/white-debt.html">https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/0...

I can& #39;t respond to all the comments here, but I will say this: if your first reaction is to get defensive, imagine what could be accomplished if you spent your energy working towards equity rather than contorting to absolve yourself and your family of wrongdoings, past or present

And to those saying "the past is the past, leave it there"...when do you think the laws, systems, and social orders that structure are lives today were created? If we don& #39;t look at the past we have really no hope of achieving justice and equity today.

See also: intergenerational wealth accumulation (and, no, just because you yourself might not be wealthy doesn& #39;t mean this isn& #39;t a thing) http://prospect.org/article/race-wealth-and-intergenerational-poverty">https://prospect.org/article/r...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter