Beekeeping or apiculture has left a small but charming legacy in European agricultural architecture, from the early 12th century to roughly the mid 19th, when the modern Langstroth hives made special buildings for apiculture unnecessary. Let& #39;s start with the bee boles!

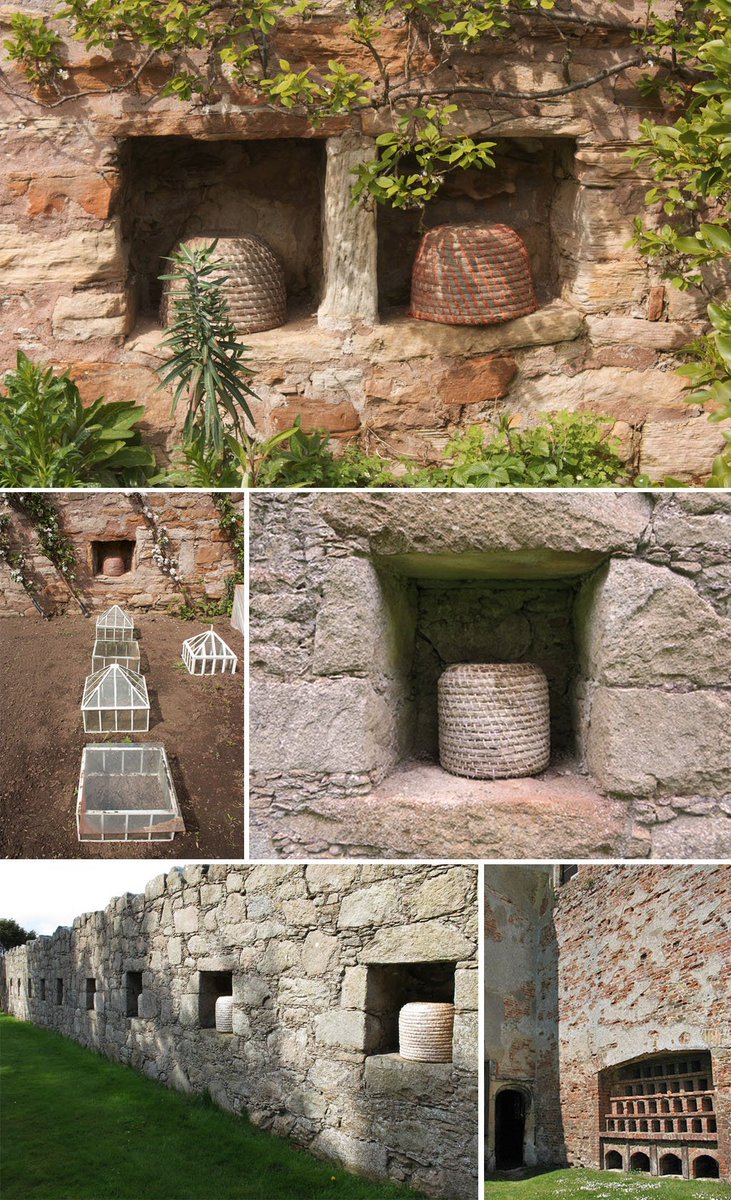

Traditionally bees were kept for their honey and wax (important in an era before sugar and indoor electric lights) in skeps, woven of straw and usually protected by a layer of dried cow dung. These skeps were vulnerable to rain and cold winds so they were usually kept under roof.

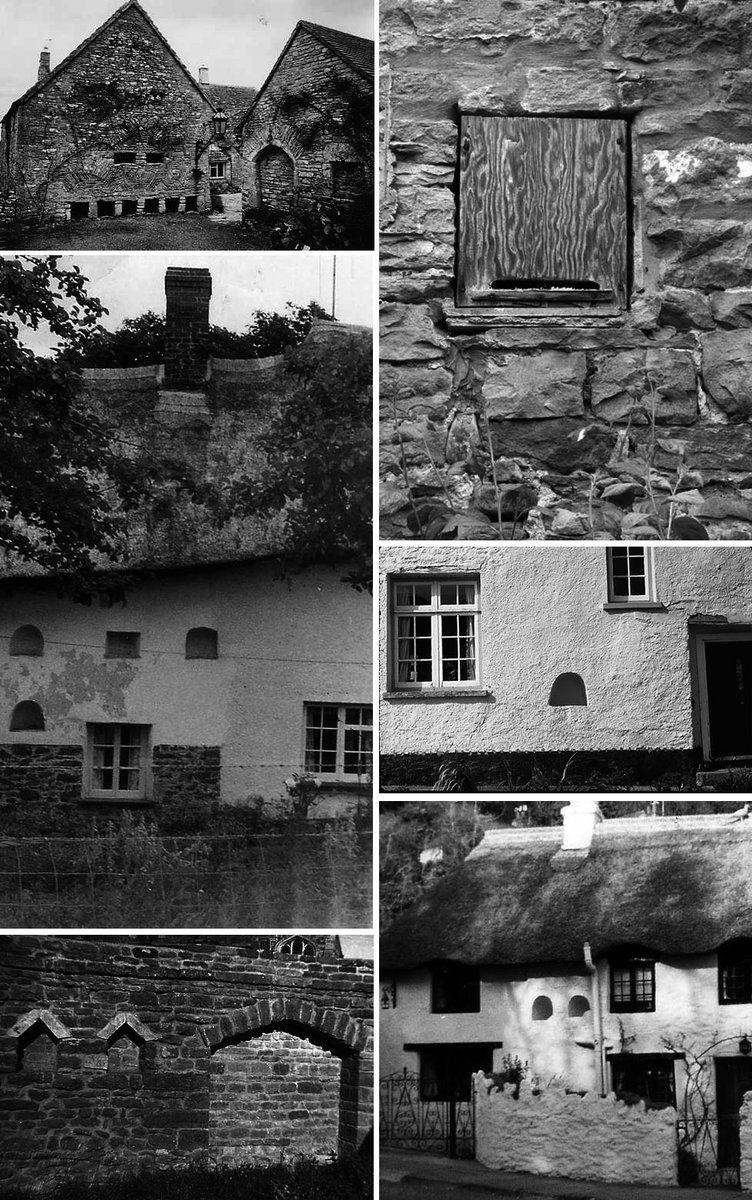

In England, after the norman conquest, as stone buildings grew more and more common in the 11th and 12th centuries, someone had the clever idea to make room for skeps in their stone walls, one niche for each skep. These were known as bee boles (that is not a typo!).

Bee boles kept the skeps out of rain and wind, and the stored heat of the sun warmed stone would help create a beneficial microclimate for the bees. Boles would always be aligned to the east or south, to make the most of the sun. They were common in brick walled gardens.

The thick walls of cob or stone cottages made it easy to put in (or carve out) a bee bole for anyone, from rich to poor. There are records of serfs and freemen alike paying their rent, taxes and tithes only in wax and honey.

Today there are about 1500 true boles in Europe (but almost all in England and Scotland), and the number is actually increasing as they are valued for their charm as well as the increasing number of skep enthusiasts.

Even with modern beekeeping, I think bee boles (or in this case bee alcoves) would be a good idea especially on the extremes of the honey bee range (Canada, Scandinavia, Greenland, Iceland, Falklands, etc.), or if you have flowers that bloom before bees are active.

Before I forget: if you are in England or Scotland and want to see bee boles, use the IBRA searchable database to find a (public) bee bole near you. http://ibra.beeboles.org.uk/search_choose.php">https://ibra.beeboles.org.uk/search_ch...

Although not strictly related to bee architecture, I just can& #39;t move on without mentioning the elegant hackle: a straw cone used to protect skeps and beelogs kept in the open from wind and rain. Simplicity itself and a common sight everywhere in Europe until the mid 19th century.

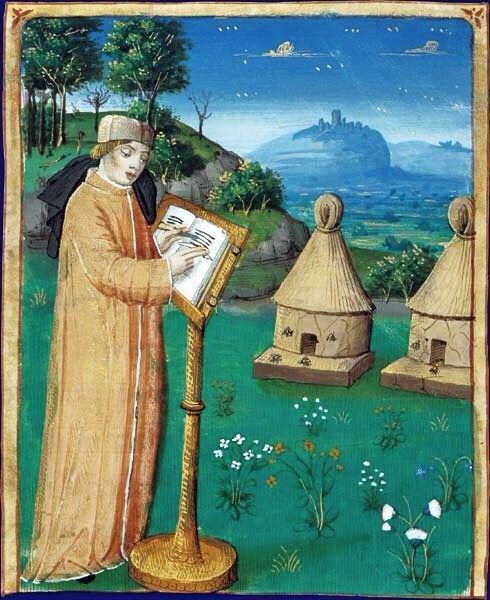

Let& #39;s talk about the humble bee house, the apiarium. While bee boles were holes or niches in walls, bee houses are the structures built with the purpose to protect bee hives from the elements, and sometimes to make work easier for the beekeeper. Here is a German "bienenhaus".

In England the most famous bee house is stone mason Paul Tuffle& #39;s 1850s Cotswold stone shelter which was moved to Hartpury from its original home in Nailsworth in the 1960. Probably the only one of its kind in the world, in a gothic-revival style. Proper architecture!

Most bee houses were purely agricultural structures, and were often located in the orchards of farms or estates, or scattered around agricultural land to help primarily in pollination. They would have been built in the local vernacular style with the cheapest possible material.

The great estates would of course built their bee houses in their own style, to match. The one at Attingham in England is a beautiful example, early 19th century and originally placed in the estate orchard, one of only two remaining Regency bee houses in the country.

Here is another rather fancy bee house, from Switzerland and located in the middle of a freshly laid orchard, late 19th century. Indoors the beekeeper would have worked in comfort, all his equipment close at hand.

Surviving bee houses can be found all over Europe, here is a selection of beautiful one from Slovenia, Germany, and Switzerland. Modern bee houses are usually wheeled, to allow for strategic placement during pollination. Renting bee hives is more profitable than honey or wax!

Maybe the grandest bee house ever constructed is found in the baroque Reggia di Caserta in Italy, the largest Royal Castle in the world. Even converted to a theatre, it is easy to imagine how absolutely charming it must have been for both royal visitors and the working men.

Probably the oldest surviving bee house in Europe is a ancient Roman cave construction in Malta, the fronts would have been covered with tiles. One theory of the origin of the name Malta itself is from the Greek word for honey, meli. The roman beekeeper was called "mellarius".

For sheer beauty, the bee houses of Carinthia and Slovenia are unbeatable. Starting in the 18th c. peasants would decorate the front end boards of the hives with colorful, often biblical, paintings, the famous "panjska končnica".

These hives were used mostly for pollination, so the breed that developed in these regions, the Carniolan honey bee, were famously quick to expand, good at defending against other insects and tame with humans. Exporting whole hives became an important side business for farmers.

The tradition of the painted hives almost died out in the late 19th century, but has recently seen a complete revival. A few hundred original boards have survived, but artists and craftsmen have picked up the tradition and they are now popular with locals and tourists alike.

The reason these boards survived outdoors for centuries is due to the material of the paint itself: locally produced linseed oil and earth pigments varnish and protects the wood itself. Sustainable art at its best. The oldest board surviving is from 1758.

Last but not least, even "wild bees" and solitary bees have had houses built for them by humans eager to help the bees in their work of pollinating fields and orchards. Here is one from Germany.

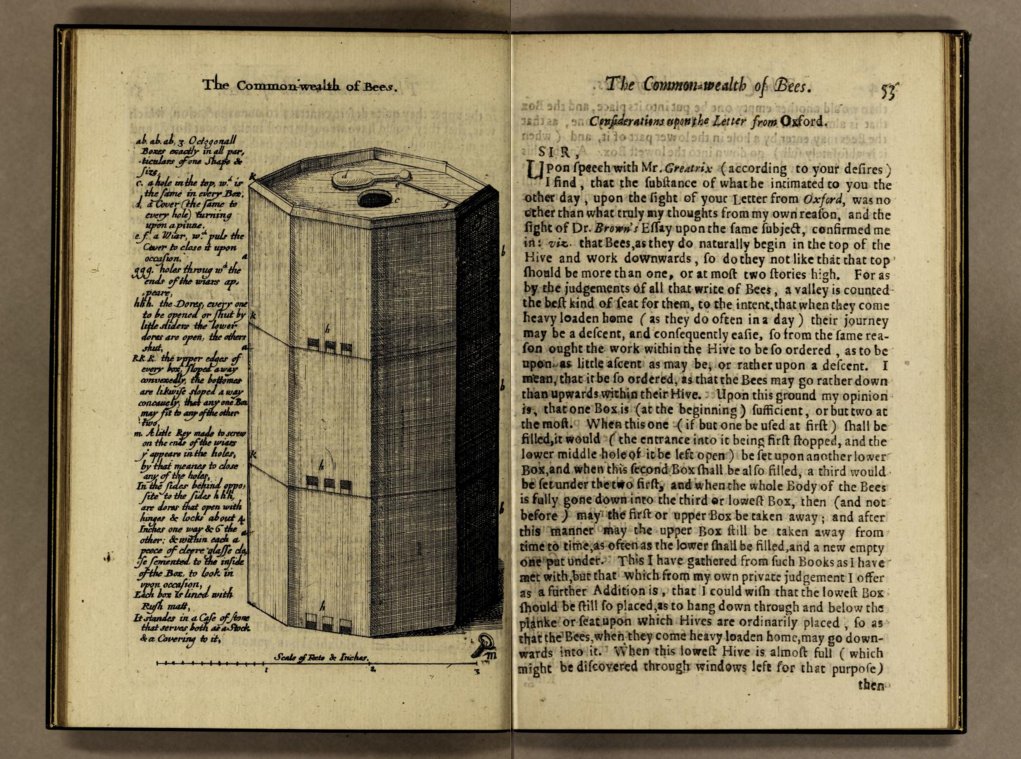

One the greatest architects and scientific minds England, Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723) created a three part octagonal hive with glass panels. Still no frames, and not being a beekeeper himself, it did not work too well (too large etc.). Here a similar idea, Hartlib, 1655.

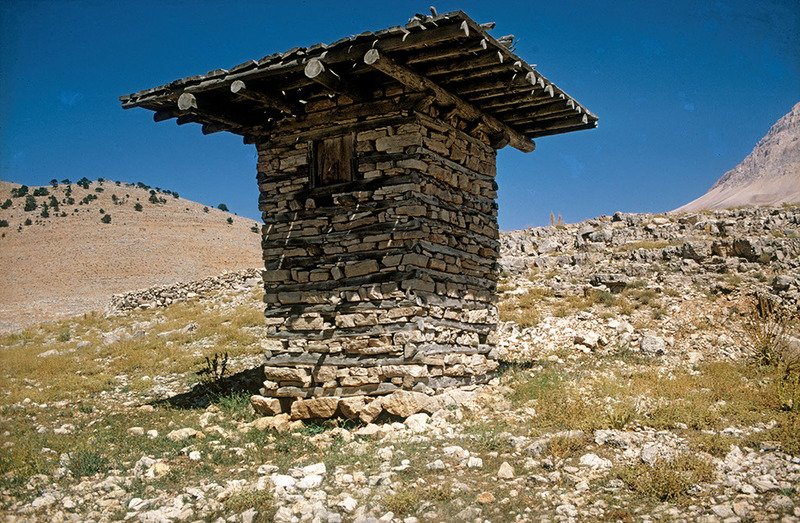

Historically, a major concern for beekeepers was how to keep wild animals from getting to the honey and destroying the hives. One way of doing it was by building towers and putting the hives on top, like these in Asia Minor (now Turkey), of which very few remain today.

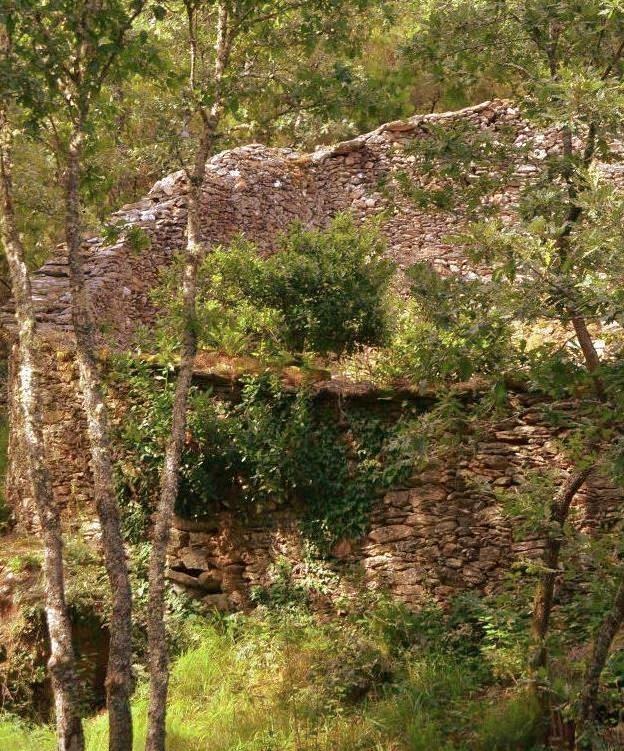

The kings of bee fortifications however, are the circular or oval walled "cities" of hives, the Albariza (or Alveriza), Oseiras or Cortín of Spain: stone drywalls up to three meters tall and built by farmers to protect their hives from bears, wolves, and bandits.

There are few wolves and bandits left in Spain, but bears have a long history of attacking apiaries. As bear populations increase, so might many old enclosures be brought back to use.

They were always built on south facing slopes in forested hills or mountains, in order to make it easier for bees to orient themselves and to have a steady supply of flowers to feed on. The forest foraging bees were often considered to produce superior honey.

The walls also protected against wind toppling the hives, and the sun heated stones helped to create a good micro climate, radiating the stored heat during the nights, prolonging the season, just like the walled gardens famously built in England.

Where they had no doors ladders were used enter the enclosure. Most commonly they housed about 40 hives. These enclosures were once common from Portugal to Greece, as far north as France.

The walled hives of France were square and called Enclos-apier, Arbinié or Naijou, and are most common in the Maritime Alps, Provence. They often came with a hut or shed to store tools or provide a place to sleep for the beekeeper during harvest time, today most are abandoned.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter