Jewish views of God that aren& #39;t the "Old Man in the Sky." A LOOONG  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="collectie" aria-label="Emoji: collectie">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="collectie" aria-label="Emoji: collectie">

Lots of people say to me "I don& #39;t believe in God." And they are surprised to hear that I, a rabbi, also don& #39;t believe in the God they don& #39;t believe in. And NEITHER do many of Judaism& #39;s greatest thinkers. 1/30

Lots of people say to me "I don& #39;t believe in God." And they are surprised to hear that I, a rabbi, also don& #39;t believe in the God they don& #39;t believe in. And NEITHER do many of Judaism& #39;s greatest thinkers. 1/30

The prayerbook makes a lot of claims: God created the world, wrote the Torah, parted Red Sea, lifts the fallen & heals the sick. What if you don& #39;t believe those things, but you care abt Judaism? What if you believe in something - but not THAT God? You& #39;re in good company. 2/

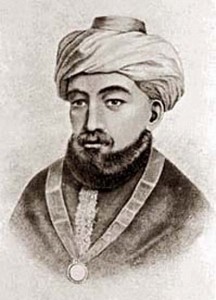

Maimonides (Rambam) is a 12 cent. rabbi, philosopher & doctor. He studied Aristotle and tried to reconcile Jewish belief w/ Aristotelian philosophy. He identified God with Aristotle& #39;s "First Cause" and believed that human reason was the way to begin to access/conceptualize God 3/

Maimonides rejected Biblical literalism, especially when Torah speaks about God in a bodily way. Anytime the Torah says God spoke/saw/formed/got angry or any other verb, he says it must be allegory. God just doesn& #39;t DO the things we do. God is entirely separate from the world. 4/

In fact, God is so separate our words can& #39;t describe God. We can& #39;t say God is "great" or "wise" bc our words don& #39;t suffice to describe an entity that has nothing in common w our world. All we can say it what God ISN& #39;T. (Not evil. Not dumb.) This is called Negative Theology 5/

17th century philosopher/"bad boy" Baruch Spinoza had an opposite take. Maimonides said God had nothing in common w the world; Spinoza said God had EVERYTHING in common with the world. He believes God is synonymous with the universe: God is everything & everything is God. 6/

That means that for Spinoza, God is not a supernatural being at all. God is the totality of what is - the stars and planets, the grass and trees, the laws of nature themselves. Even human beings are part of God. God didn& #39;t create the world - God IS the world. 7/

This raises some radical religious dilemmas. Why bother praying to a God who is simply the universe? (Spinoza says God isn& #39;t really listening.) Also, he suggests there is no such thing as free will - everything is preordained by nature (i.e. God). 8/

Then there& #39;s the issue of morality. Can there really be right and wrong if there& #39;s no commanding God?? (Maybe. We& #39;ll talk about it when we get to Hermann Cohen in the 19th century.) 9/

Either way, Spinoza& #39;s ideas got him excommunicated from the Jewish community at age 23. He lived a lonely life (though he corresponded w his idol, Descartes). He died largely penniless but his ideas went on to influence the Enlightenment & serve as the VERY BASIS OF MODERNITY 10/

Moving into modernity, Hermann Cohen (d. 1918) was a German Jewish philosopher who influenced liberal Judaism. He was out to prove that Judaism was rational. Among other things, that meant for him that God was not supernatural. 11/

For Cohen, like Spinoza, God is not a being or a person. BUT Cohen rejected Spinoza& #39;s idea that God is the world and embraced Maimonides& #39; idea that God is totally separate from the world. In fact, for Cohen, God IS the one that doesn& #39;t really exist in the world, per se: 12/

That thing is: ethics. God IS morality, he said. God IS the existence of right and wrong. Humans can access that ethical ideal through their faculty of reason: we know right from wrong (even if we don& #39;t always follow it). That& #39;s the way God "talks" to us. 13/

Cohen created a bunch of other ideas that matter Jewishly today. For example, he taught that there may not be a Messiah but a Messianic Age, and that Jews should join with non-Jews in working to repair the world. (But that& #39;s a subject for another thread.) 14/

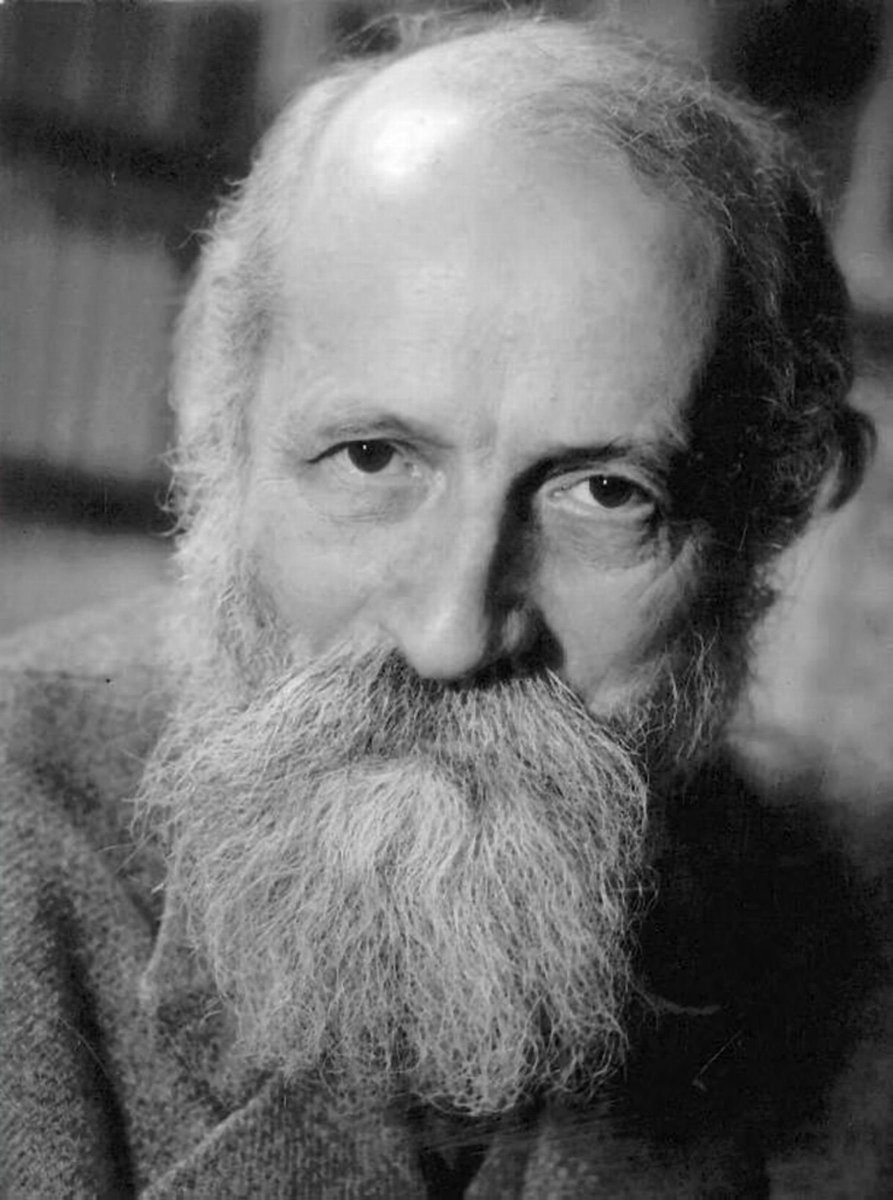

Cohen& #39;s cross-town rival was this guy: Martin Buber. In addition to having an awesome beard, he also had an awesome theology. Buber believed that God is found in relationships. His most important work is called "I and Thou." 15/

In "I and Thou" Buber teaches that there are two kinds of relationships: "I-It" relationships are the ones where we see the other as an object. (Someone bags your groceries; someone teaches you something. We learn about someone.) That& #39;s how most of our lives are spent. 16/

But once in a while we enter into "I-You" relationship. That& #39;s where we see them for who they are. For just a moment we connect one a real level where we truly see each other. For Buber, God is what makes that possible. God is the "Eternal You" we encounter in every You. 17/

In other words, God is the engine behind our capacity to connect and relate to others. In this, he was deeply influenced by Hasidic Judaism. Though he did not believe in supernatural God like the Hasidic masters, he learned from them that God exists in the space between us. 18/

(Rabbi Harold Shulweis, who lived 50 years later, said something similar but different when he said that God matters less than Godliness, and Godliness is found in human actions toward each other.) 19/

Maybe the most famous radical Jewish theologian is Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the mid-20 century founder of Reconstructionist Judaism. Kaplan was so committed to Judaism without supernaturalism that he wrote an important book called "Judaism Without Supernaturalism." 20/

Kaplan brazenly rejected many of traditional Jewish ideas, such as Chosenness, and miracles. And he asserted that God is not a being but rather the sum of the processes in the natural world that make for salvation (meaning) in life. 21/

That probably sounds a little dry. But the idea is that God is found in the places where we make meaning: forming relationships, accomplishing goals, helping others, building legacy, repairing society. God is the "sum of everything in the world that renders life significant." 22/

These things don& #39;t have to be supernatural to be significant. In fact, they are all the more significant because our lives are fleeting. Because our "salvation" (a favorite word of his) is here and now - not beyond the heavens. 23/

That means that religion, prayer, ritual, and Jewish community still matter - even if God isn& #39;t supernatural. Because those things are all human institutions, ways to find meaning/salvation in the world. 24/

So far, all of our theologians have been male. And much of their imagery and language has also been masculine. Thankfully, this began to be questioned in the second half of the 20th century. 25/

Judith Plaskow suggested in "Standing Again at Sinai" that we need to think again about our God-language. She wrote, "Only deliberately disruptive - that is, female - metaphors can break the imaginative hold of male metaphors that have been used for millennia." 26/

She suggested reaching into the sources to find images for God that are feminine and that match our experience of the Divine. Some will be anthropomorphic: Lover. Companion. Friend. Cocreator. Some will evoke God& #39;s creative & sustaining power: Wellspring. Source. Foundation. 27/

These kinds of images have begun to make their way into some liberal prayerbooks. Perhaps they better describe modern people& #39;s relationship with God than older words like "King" and "Ruler." 28/

Wow, this is the longest thread ever! Thanks for sticking with it. I& #39;m curious: which images/conceptions of God resonate with you? Do you find God in nature? In ethics? In relationships? In creative power? Somewhere else? 29/

Personally, I love that Jews are always reinventing (dare I say "reconstructing") our conceptions of and relationship with God. We read our traditional texts through modern eyes, and we find new ways to resonate with ancient ideas. 30/30

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter