It& #39;s been far too long since my last #EuropeanBios thread, but getting married is very distracting! Entry #73 is Ada Lovelace, regarded as the first computer programmer, and I am here to enthusiastically back up that story: she talked like a coder, before there was any code.

As we so often must do we have to correct her name, first: she was born Augusta Ada Byron. Oh yes, *that* Byron, he of the fabulous lifestyle and sexual scandals. She became Augusta Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, by marriage, later. https://twitter.com/seldo/status/1488315862570340352">https://twitter.com/seldo/sta...

Ada& #39;s mother was Annabelle Byron, very briefly wife to Lord Byron. Annabelle was an accomplished mathematician in her own right and also somewhat of a drama queen. Instead of putting her divorce from Byron behind her she made her whole life about it and never let anyone forget.

Annabelle was extremely determined that her daughter should not be sucked into her father& #39;s famously debauched lifestyle, to the extent that for a long time she would give Ada no information whatsoever about who her father was.

But Annabelle was all about the drama, so instead of simply not mentioning Ada& #39;s father she made him into a huge mystery. An enormous portrait of Byron hung in their house, but hidden behind a green curtain, with the servants given strict instructions not to let Ada peek.

This had the extremely predictable effect of making Ada immensely curious about who her father was, and when she eventually discovered it was the famous poet and absolute vortex of nineteenth-century scandal that was Byron she was far from disappointed.

Ada& #39;s mother was, it is safe to say, not a naturally mothering type. Neurotic, hypochondriac, and a control freak, she delegated Ada& #39;s upbringing to a series of nannies and tutors but was constantly undermining them and firing them in favor of new ones.

Ada responded to the trauma of having this kind of a parent as many children do, desperately trying to please her, attempting to imitate everything about her from a young age. This is what gave her her start in mathematics, already her mother& #39;s field.

Identified as brilliant by everyone from a very young age, Ada set out to deliberately out-do her famous father& #39;s accomplishments. She aimed to be to mathematics what he was to poetry: breaking new ground, cementing a legacy. And credit to her: she was 100% successful at this.

The Victorian age was full of advancements in science and pseudo-science and Ada enthusiastically absorbed all of it, from experiments in electricity and magnetism and the design of steam engines to "mesmerism" (an imaginary medical theory) and phrenology.

She learned shorthand (a very useful skill in her later work transcribing complex theoretical conversations) and as a young child tried to invent a way for humans to fly, confidently describing her theories and experiments in letters to her mother.

Her primary barrier to accomplishment was poor health. As a child a case of measles left her bedridden for years. Later in life she suffered from a variety of ailments for which she was prescribed the Victorian cure-all of Laudanum, aka morphine: https://twitter.com/seldo/status/1487932426751905795">https://twitter.com/seldo/sta...

She was evidently extremely dependent on laudanum for most of her short life; it seems likely that many of her ailments were in fact the effects of prolonged drug abuse, but she also completed astonishing work while on drug-fueled benders.

Aged 20, she married William King, becoming Lady King. He was rich as hell and madly in love with her and she sort of vaguely tolerated him. In response to one of his hot-under-the-collar love letters she replied thanking him for it and describing herself as "calm".

To my surprise I learned that she had three children, and indeed up until at least 1957 she had living descendants (after that the family tree gets fuzzy). She was a better parent than her mother, but that was a very low bar indeed. She described them as "irksome duties".

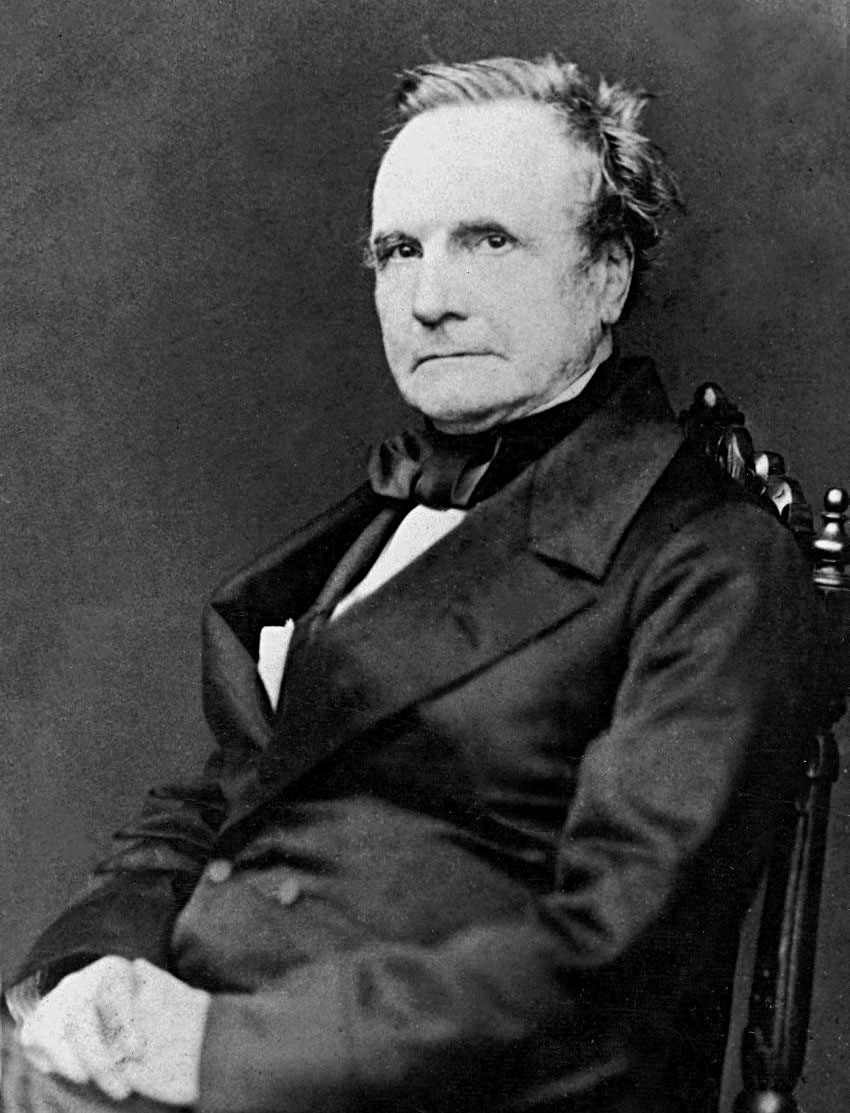

The real center of her life was Charles Babbage, one of the parents of modern computing. He designed a series of increasingly complicated mathematical calculating machines, most of which were too complex and expensive to ever be built.

She and Babbage first met when she was 18 and were immediately captivated by each other& #39;s mind and insights. They began a lifelong collaboration, in person and by letter, that laid the foundation of modern computing. It is an awe-inspiring body of work.

Ada made a theoretical leap past Babbage: she realized that the symbols his still-theoretical machines could process didn& #39;t need to be numbers. They could be music, concepts, letters, anything. She was the one to realize that Babbage& #39;s device could compute *anything*.

She predicted programming concepts that were decades away from even theoretical existence, among them loops and if-else statements. In their correspondence Babbage, no minor mind himself, gave her full credit for these insights and lamented not meeting her sooner.

All of this is all very impressive, but it was not until I heard how she talked about her work that I realized: oh, she& #39;s a *programmer* programmer. Not some proto-programmer, squint-and-you-see-it approximation. She talked about code exactly like I do: cursing it.

You can hear her debugging, in particular, an algorithm for calculating Bernoulli numbers: "I am in much dismay at having got into so amazing a quagmire & botheration with these Numbers, that I cannot possibly get the thing done today ... I am now going out on horseback."

Later she returns triumphantly: "I have worked incessantly, & most successfully, all day. You will admire the Table & Diagram extremely. They have been made out with extreme care, & all the indices most minutely & scrupulously attended to." It& #39;s all VERY familiar to a coder.

But the mind-blowing part is that not only was she holding the algorithm in her head: she was holding the *whole computer* in her head. The analytical engine, the hardware her software would run on, was never successfully built. She was *running a whole computer in her mind*.

On hardware that never existed she flawlessly executed her software, so flawlessly following the hardware that her imperfect algorithm would spit out the wrong numbers. Then she debugged the theoretical algorithm on the imaginary computer until she got it right. Incredible.

Her short, brilliant life ended at age 36 after she developed uterine cancer, which killed her in a few months. On her deathbed, she confessed something to William that made him abandon her bedside, though it& #39;s never been revealed what; potentially an affair with one John Crosse.

But there is no honorary, pseudo-, or proto- qualification about it: Ada was definitely the first programmer, as anybody who& #39;s ever programmed will attest after reading her furious accounts of attempting to debug. And she did it all on a computer that never existed.

P.S. There are only two known photographs of Ada. The first starts this thread and this is apparently the other, taken when she was a girl:

P.P.S. If you& #39;re enjoying #EuropeanBios, you can find the index to all the threads at http://EuropeanBios.com"> http://EuropeanBios.com . Also, if you are so inclined, you can now "Super follow" me on Twitter if that feature is enabled for you.

Update: thanks to @notaname I now know that Ada Lovelace has a currently living descendant, John Lytton, the 5th Earl of Lytton: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Lytton,_5th_Earl_of_Lytton">https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/John...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter