I promised an #Enceladus thread yesterday; it starts here! Let& #39;s take a look at this tiny, but all the more interesting icy moon of Saturn!  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪐" title="Planet mit Ringen" aria-label="Emoji: Planet mit Ringen"> https://twitter.com/People_Of_Space/status/1391834523294437384">https://twitter.com/People_Of...

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪐" title="Planet mit Ringen" aria-label="Emoji: Planet mit Ringen"> https://twitter.com/People_Of_Space/status/1391834523294437384">https://twitter.com/People_Of...

Though discovered already in the late 18th century by William Herschel, we had long known extremely little about it.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔭" title="Teleskop" aria-label="Emoji: Teleskop">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔭" title="Teleskop" aria-label="Emoji: Teleskop">

That changed with the Voyager flybys! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🛰️" title="Satellit" aria-label="Emoji: Satellit">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🛰️" title="Satellit" aria-label="Emoji: Satellit">

That changed with the Voyager flybys!

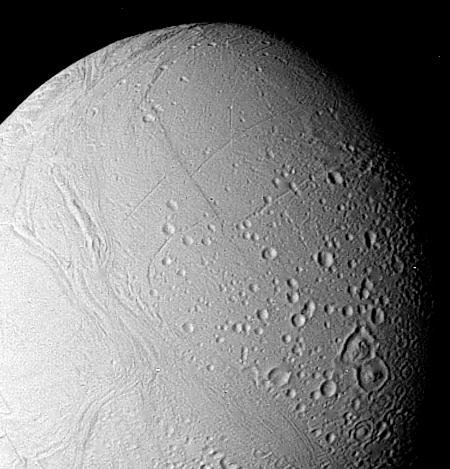

This image was taken by Voyager 2 on August 25, 1981, from about 110,000 km away. It shows cratering, but also bright ice, grooves, some crater-poor areas. That suggested parts of the surface were very young - the tiny moon was active!

Here& #39;s a mosaic from Voyager 2 images showing the marked difference between the cratered northern hemisphere and the crevassed young terrain of the southern one. Something was going on!

I keep saying "tiny" moon. How tiny exactly?

It& #39;s about 500 km across (our Moon is nearly 3,500 km across) - about the length of the Czech Republic, where I live, from west to east!

In the comparison, Enceladus is in near the lower left corner.

It& #39;s about 500 km across (our Moon is nearly 3,500 km across) - about the length of the Czech Republic, where I live, from west to east!

In the comparison, Enceladus is in near the lower left corner.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter https://twitter.com/People_Of..." title="I promised an #Enceladus thread yesterday; it starts here! Let& #39;s take a look at this tiny, but all the more interesting icy moon of Saturn! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪐" title="Planet mit Ringen" aria-label="Emoji: Planet mit Ringen"> https://twitter.com/People_Of..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

https://twitter.com/People_Of..." title="I promised an #Enceladus thread yesterday; it starts here! Let& #39;s take a look at this tiny, but all the more interesting icy moon of Saturn! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🪐" title="Planet mit Ringen" aria-label="Emoji: Planet mit Ringen"> https://twitter.com/People_Of..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

That changed with the Voyager flybys! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🛰️" title="Satellit" aria-label="Emoji: Satellit">" title="Though discovered already in the late 18th century by William Herschel, we had long known extremely little about it. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔭" title="Teleskop" aria-label="Emoji: Teleskop">That changed with the Voyager flybys! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🛰️" title="Satellit" aria-label="Emoji: Satellit">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

That changed with the Voyager flybys! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🛰️" title="Satellit" aria-label="Emoji: Satellit">" title="Though discovered already in the late 18th century by William Herschel, we had long known extremely little about it. https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔭" title="Teleskop" aria-label="Emoji: Teleskop">That changed with the Voyager flybys! https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🛰️" title="Satellit" aria-label="Emoji: Satellit">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>