The eighth and final thread on the life of Hafsa bint Sirin. Here I offer my final thoughts and readings demonstrating that this woman so carefully depicted as a recluse, in reality, lived a full social life.

I’ve been showing that the reporters goals were not objective history, but rather to produce teaching stories and the teaching was to depict women’s piety and authority as silent and reclusive. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1388875713697157120?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

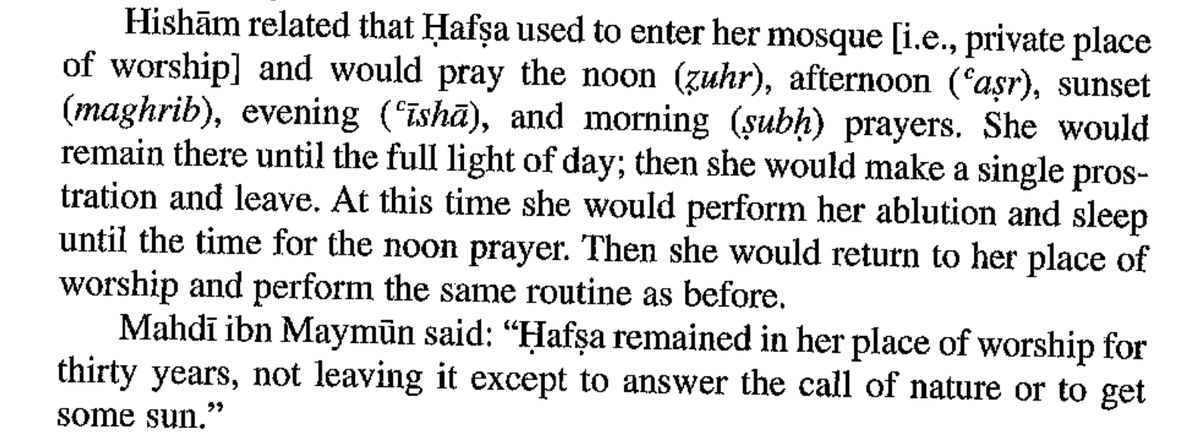

So let’s take our final look at these accounts. Hafsa basically never leaves her room except to get some sun and use the washroom. Read the account in this image. Really. Read it. Uh. Hrm. Huh? Is that so?

What do we know: Women raised their children as part of a community of other women, members of their extended families, and neighbours in which the shared experience of the cycles of life create ineluctable social bonds. So why not mention them? https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1388875721238532097?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

Just because these relationships are not documented in the texts does not mean that they did not exist. There is other evidence of women’s social world that allows us to be safe assuming that pious and mystic women had lives beyond the solitude that the sources ascribe to them.

This is why, in my Sufi Mysteries, I explore the complex lives of the women surrounding Junayd’s Sufi order. All of what I write is possible based on wide-ranging evidence that supports the notion these women led full, loving, contentious, and pious lives. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1378004836629745667?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

To do history and write historical novels, I close my eyes and imagine the place, circumstances, actions, and words based on research. I find I consider details I wouldn& #39;t have noticed otherwise. The story of her brother& #39;s death from plague is an example. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1386310380821966848?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

So: Given the structure of homes at the time in Basra and the common practice of extended families living in related quarters, Hafsa, her son, and his family probably lived in a grouping of rooms with a shared courtyard.

Her son visited with her regularly. Given the social roles of family members during that time, it is likely that her daughter-in-law helped out with cleaning and cooking. But after al-Hudhayl died, his wife probably returned to her own family.

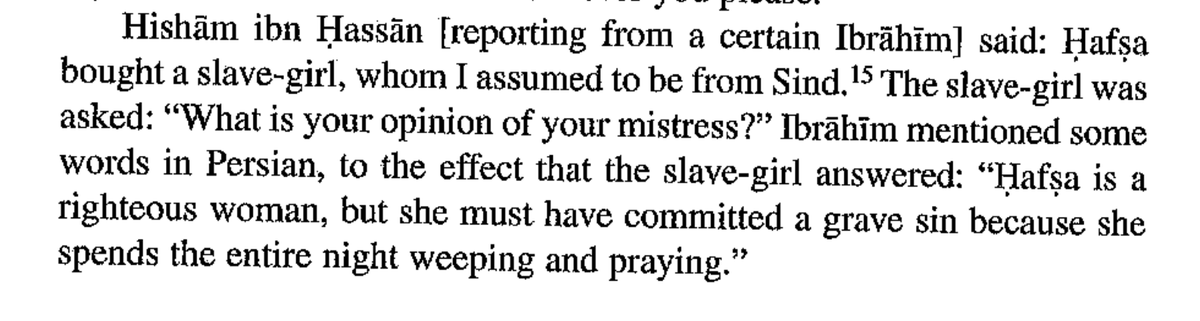

After his death, Hafsa is reported to have purchased a girl from Sind to do the household chores. This girl was asked about her opinion of Hafsa. Portrayed as a young innocent, she says her owner was righteous, but says she must have sinned gravely to weep so much in prayer.

Let’s pause for a moment before returning to Hafsa’s story: Imagine what it would be like for this unwilling companion to be asked to offer her assessment of her owner by eager men. How might she have felt? Imagining that might make us uncomfortable.

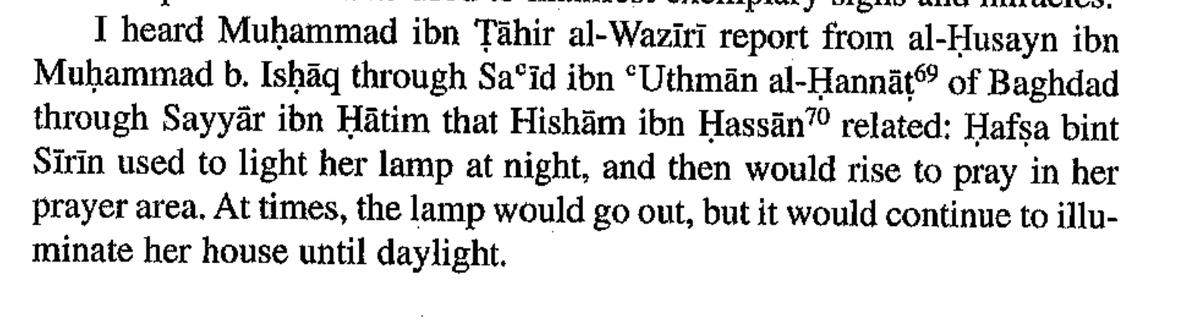

Recall that her son stayed awake at night feeding her fire. The girl from Sind may have too, yet would also have had to work the next day while Hafsa slept. But perhaps Hafsa finally bought that lamp mentioned in Sulami’s story? If she can afford a person, she can afford a lamp.

We don’t know. But I feel it is important to allow ourselves to be uncomfortable as we imagine all the possibilities of the lives of enslaved people. Sitting with discomfort is at the heart of cultivating ethics. Not deflecting or reaching for easy answers deepens understanding.

Back to Hafsa& #39;s story: Despite supposedly never leaving her room and prayer except to answer the call of nature, a sister is said to have visited her often. So what happened? Did her sister just sit outside waiting for a quick wave as Hafsa went to relieve herself? Not likely.

We also don& #39;t have any stories about another sister, Karima, who was a devoted worshipper. Did they never visit each other (both maybe never left their rooms)? Or did they visit each other and pray together? The latter is more likely.

Her brother Muhammad’s wife is said to have been almost continuously pregnant and to have lost nearly all her children. These were hard times in Basra and Muhammad ibn Sirin had little interest in business.

His work as an itinerant cloth salesman seems to have been more of an opportunity for him to sit with other scholars and pious folk than sell cloth and his wife and children seem to have lived in dire poverty.

Given Hafsa’s close relationship with her brother and love of her own child for whom she would grieve so deeply, it is hard for me to imagine that she never came to the aid of her sister-in-law.

No doubt her sister-in-law’s own family would be there for her, too, as well as other members of Hafsa& #39;s family. In this cultural context, it would be expected that all the members of extended families would care for one another.

Perhaps more telling for the silence in the texts, we never hear of any grandchildren or her siblings’ children visiting her. She had twenty-two full or half brothers and sisters and valued her family. A number of her siblings were also scholars and pious worshippers.

It seems impossible that any of their children, not to mention Muhammad ibn Sirin’s surviving son who would become a scholar himself, never sat with her to learn Qur’an and Hadith as a child.

I mean, wait, didn& #39;t Muhammad ibn Sirin sent his own companions to study with his sister? But he chose not to send his son who would himself become a pietist and transmitter of hadith? Not likely. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1386310365353418756?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

And let’s return to the enslaved girl from Sind purchased by Hafsa to do her housework. She was portrayed as a youthful innocent, not understanding Hafsa’s weeping in prayer. Hafsa never taught her what that was all about?

Hafsa was the child of enslaved parents who had the chance to better themselves and she became a scholar as result of their relations while enslaved. Did Hafsa deny her the same? More likely, her ignorance an assumption of the men who demanded her opinion. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1383801015938342923?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

Just because these relationships are not documented in the texts, does not mean we cannot logically infer the possibility of them given all the other evidence to hand. Recall how much she grieved over the death of her brother, Yahya. She had feelings for these people.

So despite almost no mention of these social relations in the reports, I feel comfortable assuming that Hafsa would have spent a good amount of time with her beloved sisters, sister-in-law, daughter-in-law, their children, not to mention the girl from Sind.

In past threads, I’ve shown she had a loving, bustling childhood, in later life she was busy with students, taught women how to prepare bodies for the grave, made a successful legal argument in the home of the governor of Basra, was close with Anas ibn Malik, and more.

If my understanding of her later life as filled with peers, family, friends and her students is correct, then it is impossible, as the sources report, that she only left her place of prayer long enough to relieve herself and get some sun.

This claim becomes even more implausible when we consider that the very reports attesting to her extraordinary solitude are transmitted by people who so often spent time in her company: the young men who studied Qur’an with her on a regular basis.

In particular, Hisham visited with her socially in her old age, learning from her, taking advice from this wise old woman, and listening to her as she shared stories about her relationship with her son.

Most likely, then, Hafsa stayed awake in worship from the evening prayer to the morning prayer, slept until the midday prayer, then received visitors, students, or visited others during the afternoon hours, performing the afternoon and sunset prayers at their appointed times.

This schedule would leave her ample time to take part in the social life of her home as well as teach her classes on the Qur’an and Hadith and stay up all night in prayer.

We know, too, that she traveled for Hajj several times in the company of others and visited the homes of elites in Basra.

Finally, consider that at least on cold nights, her son, and then perhaps the enslaved girl from Sind, kept her company through the long nights in prayerful solitude to feed the fire.

All of which begs the question, when was this recluse ever alone?

And so we come to the end of my blogs on Hafsa. If you missed any, I have them linked in order on my master thread. They& #39;re cool, really! Lots of goodies showing that the story you& #39;ve been told about good women being silent is not historically accurate! https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1378004836629745667?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

As always, if you like the way I think about history you might be interested in exploring the world of my historical mysteries: The Sufi Mystery Quartet. My website gives a lot of background, reviews, and I read the first two chapters of The Lover! http://www.llsilvers.com"> http://www.llsilvers.com

Next week, I’ll turn to a different matter....discussing why I do not use Joseph Campbell’s much hailed and used (almost required) “Hero’s Journey” in my novels and the classical Muslim journey of human transformation instead. Thank you!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter