A thread about hinges.

Or, Sutton Hoo, Problem-Solving, and Syncretic Workshop Practice.

If you can suggest good examples of hinges from the Early Medieval, Late Iron Age, or Late Roman periods, please post them in the replies.

(Images from the British Museum, mostly).

Or, Sutton Hoo, Problem-Solving, and Syncretic Workshop Practice.

If you can suggest good examples of hinges from the Early Medieval, Late Iron Age, or Late Roman periods, please post them in the replies.

(Images from the British Museum, mostly).

The Sutton Hoo ship burial is famous for several reasons - the quality of the metalwork, the apparent wealth of the person buried there, and their connections to an international network of influence and precious materials.

But really, we should be getting excited about hinges.

But really, we should be getting excited about hinges.

A hinge is a type of articulation. Lots of objects have articulation, eg. a chain is articulated at every link, but they move freely in any direction.

Hinges provide controlled articulation, restricting the direction of movement, and sometimes the distance of movement.

Hinges provide controlled articulation, restricting the direction of movement, and sometimes the distance of movement.

The chain above is from one of the shoulder clasps. The chain is flexible, but its purpose is security - it connects the pin or bolt to the body of a clasp. It is a very posh version of the safety chain on a modern item of jewellery.

Those bolts pass through a hinge-like assemblage. I say hinge-like, because the purpose is to collect, rather than articulate.

Nonetheless, this is an excellent example of hinge design. The shoulder of the wearer limits movement in one direction....

Nonetheless, this is an excellent example of hinge design. The shoulder of the wearer limits movement in one direction....

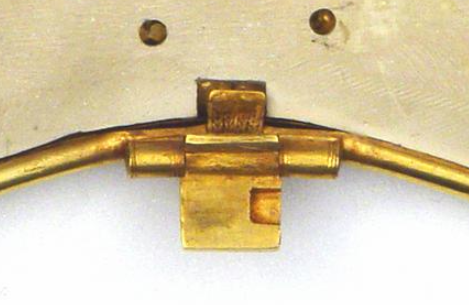

...and the off-set placement of the hinge leaves a lip to limit movement in the other direction. The hinge tubes appear to be soldered onto a & #39;saddle& #39; the runs the length of the hinge, and is a further sign of the excellent quality of the metalwork (as if you need more evidence).

Sutton Hoo doesn& #39;t have just one hinge, of course. It has several. While I haven& #39;t undertaken a thorough study of hinges across Europe, I don& #39;t recall seeing anything else that matches the range and the ingenuity of the Sutton Hoo examples.

So, where do we find hinges? Perhaps most obviously, looking around the room you are in right now, are doors, and lids. The Early Medieval was no different. However, these are usually large, simple hinges, and each hinge is made of two components.

Hinges are primarily functional, and ergonomic - they link two objects together, and if they are worn on the body, they must be comfortable, and conform to the needs of the wearer.

For example, buckles, which must hold a strap or belt securely, while allowing easy removal.

For example, buckles, which must hold a strap or belt securely, while allowing easy removal.

Helmets are another example - cheek flaps & neck guards are typically separate pieces, joined to the helm such a way that they provide protection while conforming to the body.

However, the Sutton Hoo helmet has a rather boring hinge, thought to be pieces of leather, riveted on.

However, the Sutton Hoo helmet has a rather boring hinge, thought to be pieces of leather, riveted on.

Few Early Medieval helmets have been found, but those that have display considerable diversity of design and decoration, and - because it& #39;s the most exciting topic in the world - use of hinges. The Coppergate and Wollaston helmets have metal hinges, but of different types.

This suggests that while there are similarities in the form and decoration of helmets, each one is an exercise in problem-solving, rather than copying an existing model.

In that sense, the Sutton Hoo helmet displays a surprising lack of ingenuity - but it does the job.

In that sense, the Sutton Hoo helmet displays a surprising lack of ingenuity - but it does the job.

More to follow, but I need to do some housework!

I want to take a brief interlude to talk about the Staffordshire Hoard (images from the monograph), which is not very hinge-y.

Here, the cheek pieces are thought to allow very limited articulation, being riveted onto the helmet. Hinge-like, but not really a hinge.

Here, the cheek pieces are thought to allow very limited articulation, being riveted onto the helmet. Hinge-like, but not really a hinge.

In addition, there are 3 buckles (maybe possible fragments of a 4th), one of which has a similar form to the great gold buckle from Sutton Hoo, but in silver, while the others are gold, but of a simple form with minimal decoration - the buckle plate is bent to form the hinge.

When you consider the huge size of the hoard, that is a small number. That could be for several reasons - eg. that few hinged items were made in precious metals, and therefore not deposited, or perhaps the depositor was focused on particular types of object, like pommels.

What is clear is that despite the amazing metalwork in the @staffshoard, comparable and maybe even connected to examples from Sutton Hoo, we don& #39;t have much evidence for hinge designs that come close to the Sutton Hoo corpus.

This is partly deposition bias. A royal ship burial with all the trimmings, so plenty of metalwork to be worn on the body (compared to sword fittings, shield mounts, and suchlike) & even pragmatic objects are decorated, & made in gold, which tends to survive in the ground

Let& #39;s look at some of these in detail. First up is the purse lid, decorated with awe-inspiring cloisonné designs that hint at a complex mythology stretching beyond the borders of the British Isles.

But who cares about that?!? We& #39;re here to talk hinges.

But who cares about that?!? We& #39;re here to talk hinges.

There are 4 hinges, with 3 layouts. The top centre hinge is the largest, consisting of 5 sections of tube, 3 soldered directly onto the frame of the purse lid, while the other 2 are attached to a composite hinge plate (it looks like a solid piece, but it isn& #39;t,).

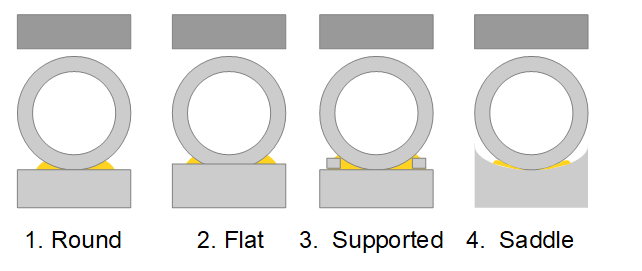

In cross-section, soldered hinges will look like one of these. The shoulder clasps, mentioned earlier, have distinct saddles (4.). On the top of the purse lid, they are either type 1. or 2, and all three hinges here have the same basic design.

Curiously, the 4th hinge is somewhat different. Perhaps we shouldn& #39;t be described, because this one seems to be a fastener. The soldering here appears to be type 3 - supported, and the supports are just slivers of gold on both sides of the tube.

That could represent a repair due to breakage, or a precaution against breakage. Unlike the top hinges, this one would be manipulated with the fingers &(excitement!) it appears to be a sprung hinge - the hinge plate is L-shaped & would push against the strip of filigree behind it

Not only that, but the hinge plate has an indentation, presumably to keep the purse shut. This is a multi-functional hinge, and I think it displays some excellent problem-solving; the slivers of gold might be a response to an unexpected problem of flexibility.

More hinges. Next up is the great gold buckle. It weighs over 400g, and is made from a mix of cast and fabricated components. This is very difficult to assess from photographs, compared to the rest, and that might be more than just coincidence!

While it should impress anyone by weight alone, this is kind of a & #39;puzzle buckle& #39;. @SueBrunningBM explains the object better than I can, in this recent lecture. https://youtu.be/hTthNTttsVY ">https://youtu.be/hTthNTtts...

First, it is decorated with interlaced creatures. In the photo above, see how many you can spot! There are lots of them, and it rewards time spent & #39;solving& #39; it.

Second, despite the weight, it is not a solid buckle - it is a box, which can only be seen from the back.

Second, despite the weight, it is not a solid buckle - it is a box, which can only be seen from the back.

There are 2 separate hinges - one for the buckle loop and tongue, and another for the box. The latter is a slim, neat hinge, reminiscent of the shoulder clasp assemblage. It is difficult to assess from the photographs, but it doesn& #39;t seem to have a saddle.

It has been suggested that something might have been kept in the box. Certainly a lot of effort was put into giving it a lid that can be opened, but on the other hand, there is a gap indicating that the belt was attached inside.

Third, the buckle hinge, which is difficult to see because it covered by the unusually large circular tongue plate (remember, there is a similar example in the Staffordshire Hoard).

Tongue plates are not that unusual, but they are rarely as large and thick as this one.

Tongue plates are not that unusual, but they are rarely as large and thick as this one.

So far, the hinges I& #39;ve discussed have been fabricated from tubes, but here, some of the components must have been cast with perforations for the pin to pass through - the wall thickness is significant, compared to the diameter of the pin.

The pin appears to be riveted into a countersunk hole; I suspect that it was originally flush, but movement of buckle loop has caused it to stretch.

The loop has a complex saddle arrangement, which blends perfectly w/ the overall form of the buckle, but puts stress on the pin.

The loop has a complex saddle arrangement, which blends perfectly w/ the overall form of the buckle, but puts stress on the pin.

There are objects with a similar form, but the great gold buckle is particularly well made, as you can see from this less impressive example (perhaps a poor copy?) from France: https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1891-1019-1">https://www.britishmuseum.org/collectio...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter