Ulysses S. Grant, May 6, 1864, in the Wilderness, Virginia, upon hearing an excited officer declare that he knew what Lee would do next after the Confederates launched an attack at dusk:

It had been a rough two days for the general-in-chief. One of his West Point classmates, Alexander Hays, had been killed on May 5. Grant was shaken when he heard the news.

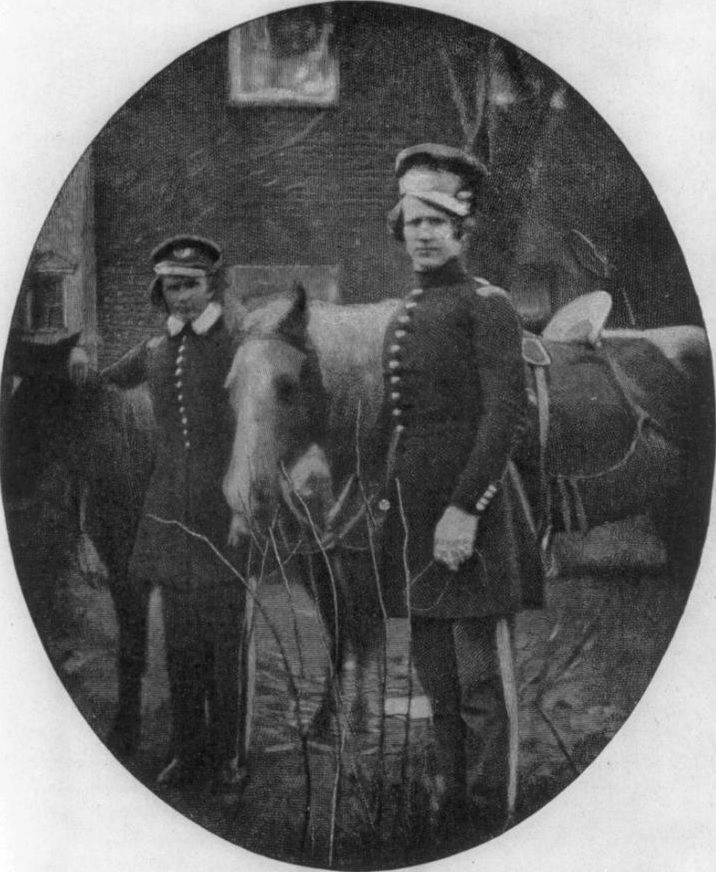

Hays had graduated a year after Grant. Here is an image of the two men (Hays is in the foreground):

Hays had graduated a year after Grant. Here is an image of the two men (Hays is in the foreground):

Hays& #39;s death meant that there was one less friendly face for Grant in the Army of the Potomac, and there were not many (although he knew Winfield Scott Hancock, among others).

Hancock had opened the fighting on May 6 by attacking Lee& #39;s right. The attack was initially successful.

Hancock had opened the fighting on May 6 by attacking Lee& #39;s right. The attack was initially successful.

Lee rode out to rally his men. Meanwhile, another of Grant& #39;s prewar comrades, James Longstreet, counterattacked, and drove Hancock back to where he started.

Longstreet fell, a victim of friendly fire, just like Stonewall Jackson did just over a year before.

Longstreet fell, a victim of friendly fire, just like Stonewall Jackson did just over a year before.

As dusk approached, another Confederate attack against the extreme Union right created quite a stir, resulting in Grant snapping at the officer.

Grant began the day with two dozen cigars. When Hancock visited him that evening, Grant dug in his pocket to find only one remained.

Grant began the day with two dozen cigars. When Hancock visited him that evening, Grant dug in his pocket to find only one remained.

After matters had settled down, Grant went into his tent. Charles F. Adams, Jr. noted that "I never saw a man so agitated in my life." Some reports claimed that he broke down. Others made no such claim. In any case, he soon emerged, calm, composed, collected.

In years to come the story of Grant breaking down became a major point of debate in accounts of the battle and biographies. Did he break down? Why? What should we make of it?

Implicit in the discussion was a notion that "breaking down" was somehow "unmanly." Real men don& #39;t cry, I guess. Grant& #39;s detractors liked to believe he broke down, while his defenders usually dismissed the story.

I have always thought the Adams description valuable, because the accounts of Horace Porter (Grant defender who was present) and James Wilson (Grant detractor who wasn& #39;t present) are part of a larger portrait both men wanted to paint. Adams had no skin in this game.

As to why Grant became agitated I think the answer& #39;s an easy one. It wasn& #39;t Lee. It was the Army of the Potomac& #39;s officer corps.

Lee lived rent-free in their heads too often.

Lee lived rent-free in their heads too often.

In the weeks to come Grant would call upon his generals, officers, and men to be aggressive, to take the fight to the foe, to attack whenever there was an opportunity.

Sometimes he was wrong. Sometimes he was too aggressive. Sometimes he should have considered what Lee might do.

Sometimes he was wrong. Sometimes he was too aggressive. Sometimes he should have considered what Lee might do.

But Grant achieved one thing, and that was everything: Robert E. Lee never again held the upper hand.

Watching the parade of Union generals come and go, Lee once remarked to Longstreet that he dreaded that one day the Yankees would find a general he did not understand.

Watching the parade of Union generals come and go, Lee once remarked to Longstreet that he dreaded that one day the Yankees would find a general he did not understand.

He met that general on April 9, 1865.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter