1/ Our new pre-print produces county-level estimates of excess mortality in 2020 for over 3100 counties across the United States – for use in local health policy and planning.

Thread.

Thread.

2/ Prior work reveals that many excess deaths in 2020 were not directly assigned to COVID-19 on death certificates. The percent of unassigned deaths also varies across US states. For example, see Woolf et al. and earlier work by @WeinbergerDan et al. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2778361">https://jamanetwork.com/journals/...

3/ However, few studies to date provide information on patterns of excess mortality and excess deaths not assigned to COVID-19 at the county-level.

Our new study attempts to fill this gap:

Link: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.23.21255564v2">https://www.medrxiv.org/content/1...

Our new study attempts to fill this gap:

Link: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.04.23.21255564v2">https://www.medrxiv.org/content/1...

4/ In an earlier paper, we examined sociodemographic factors associated with excess deaths not assigned to COVID-19 for groups of counties. We did not report estimates for individual counties or conduct a detailed examination of geographic variation. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.31.20184036v5">https://www.medrxiv.org/content/1...

5/ Areas in dark red represent areas where less than 75% of excess deaths were assigned to COVID-19, highlighting areas (i.e. South East Central Division, Appalachia, Mountain states) where under-reporting of COVID-19 deaths or a significant number of indirect deaths occurred.

6/ Overall, among counties with significant increases in excess deaths, we found that 18% of excess deaths were not assigned to COVID-19. More excess deaths were not assigned to COVID-19 in the South and West regions and in nonmetro vs. metro areas.

7/ New England was the only Census Division where directly assigned COVID-19 deaths exceeded excess deaths. This finding was limited to metro areas. The figure below shows Middlesex County, MA. Nonmetro areas in New England had a substantial number of unassigned excess deaths.

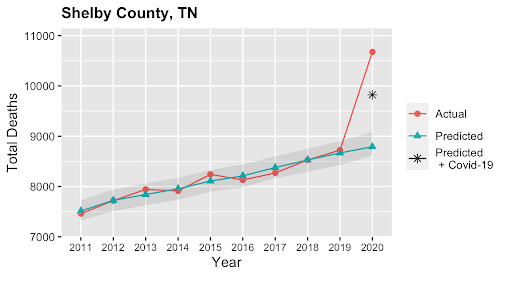

8/ Importantly, we also found many counties where the excess death rate greatly exceeded the directly assigned COVID-19 death rate, suggesting that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been effectively hidden in these areas. This figure below shows Shelby County, TN.

9/ Excess deaths not assigned to COVID-19 may reflect under-reporting of COVID-19 due to limitations in testing and unfamiliar manifestations of COVID-19, especially early in the pandemic, as well as various social, political, and health care factors.

10/ Coroners are elected officials who typically lack medical training and as a result may underreport COVID-19 deaths. Partisan differences may also affect the likelihood that an individual or family pursues testing while alive or a certifier pursues post-mortem testing.

11/ Excess deaths not assigned to COVID-19 may also reflect indirect deaths related to reductions in health care or the social and economic consequences of the pandemic (e.g. see recent paper by @AriBFriedman https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/emp2.12349)">https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.10...

12/ Regardless of the cause, our paper makes clear that measures of direct COVID-19 mortality were not an accurate measure of excess mortality in many counties across the United States.

13/ A more complete accounting of COVID-19 deaths in local communities using excess deaths could lead to increased public awareness and vaccine uptake, particularly in areas where the official death counts suggested the pandemic had a limited impact.

14/ Furthermore, FEMA is now providing funeral assistance for those whose death certificate includes COVID-19. The families of decedents who died from COVID-19 but whose death certificate went unassigned will be unable to benefit from this policy.

https://www.fema.gov/disasters/coronavirus/economic/funeral-assistance">https://www.fema.gov/disasters...

https://www.fema.gov/disasters/coronavirus/economic/funeral-assistance">https://www.fema.gov/disasters...

15/ Finally, some counties may have experienced reductions in mortality from other causes of death during the pandemic. This prompts an important question for future research: did these reductions occur uniformly, or were there differences by age, race/ethnicity, and education?

16/ @KBibbinsDomingo @ch272n @MariaGlymour @raycatalano and colleagues at @UCSF have done important work in this area using data from CA. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2774273">https://jamanetwork.com/journals/...

17/ @ewrigleyfield and colleagues at the University of Minnesota have also leveraged excess mortality data from Minnesota to reveal that racial/ethnic inequities in excess mortality greatly exceed those reported by direct COVID-19 mortality. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2378023120980918">https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/...

18/ These findings highlight what @DrIbram of @AntiracismCtr wrote in @TheAtlantic: “We still have only partial visibility into precisely who coronavirus patients really are. Data inequality, and all its shadows, is the norm.” https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/05/we-still-dont-know-who-the-coronaviruss-victims-were/618776/">https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/arc...

19/ This work is preliminary and has not been peer-reviewed. Feedback would be welcome and much appreciated.

20/ Limitations of our study include: (1) use of provisional data from 2020, which was last updated as of April 21, 2021, (2) lack of disaggregated data by cause of death, age, race/ethnicity, and education, and (3) use of cumulative data rather than weekly or monthly trends.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter