2/ In post-independence Sri Lanka there were enormous changes in education. The Sinhala Only Act of 1956 and the Tamil Language (Special Provisions) Act of 1958 changed the medium of instruction in secondary schools from English to Sinhala and Tamil.

3/ This more than tripled secondary school enrolment, as a huge number of students from non-elite backgrounds who didn’t speak English were now able to study at secondary schools in their first language.

4/ But this led to problems for universities, as the number of students seeking university admission multiplied nearly sixfold from 5,200~ in 1960 to 30,400~ in 1969/70. By contrast, the number of places available only doubled, from 1,800~ in 1960 to 3,450~ in 1969/70.

5/ The increase in places was also largely in the arts faculties, which led to increasing numbers of unemployed arts graduates through the 1960s. This in turn increased competition for entry into the science-based faculties (engineering, medicine, physical sciences etc.)

6/ But not many schools offered science up to grade 12, & nearly half these concentrated in the Western & Northern provinces, largely populated by SL Tamils and Low-Country Sinhalese. Those two provinces provided over half the total admissions to science-based faculties in 1969.

7/ Admission to science-based courses in 1970 comprised of 39.8% SL+Upcountry Tamils (who were 20%~ of the population) compared to 57.7% Low-Country+Kandyan Sinhalese (72%~ of the population).

8/ The medium of instruction at universities had also changed from English to Sinhala & Tamil by 1969. All university entrance exams now had two scripts, marked by two sets of examiners. Complaints of favouritism which weren’t as common under English exams increased.

9/ All of this set the stage for the series of policies that were put in place by the United Front govt elected in 1970. These policies came in four consecutive schemes:

10/ Scheme 1: minimum marks adjustment. Based on unsubstantiated rumours that 60% of engineering admissions were Tamil medium candidates due to over-marking by Tamil examiners, the govt set lower qualifying marks for Sinhala medium candidates into all courses except arts.

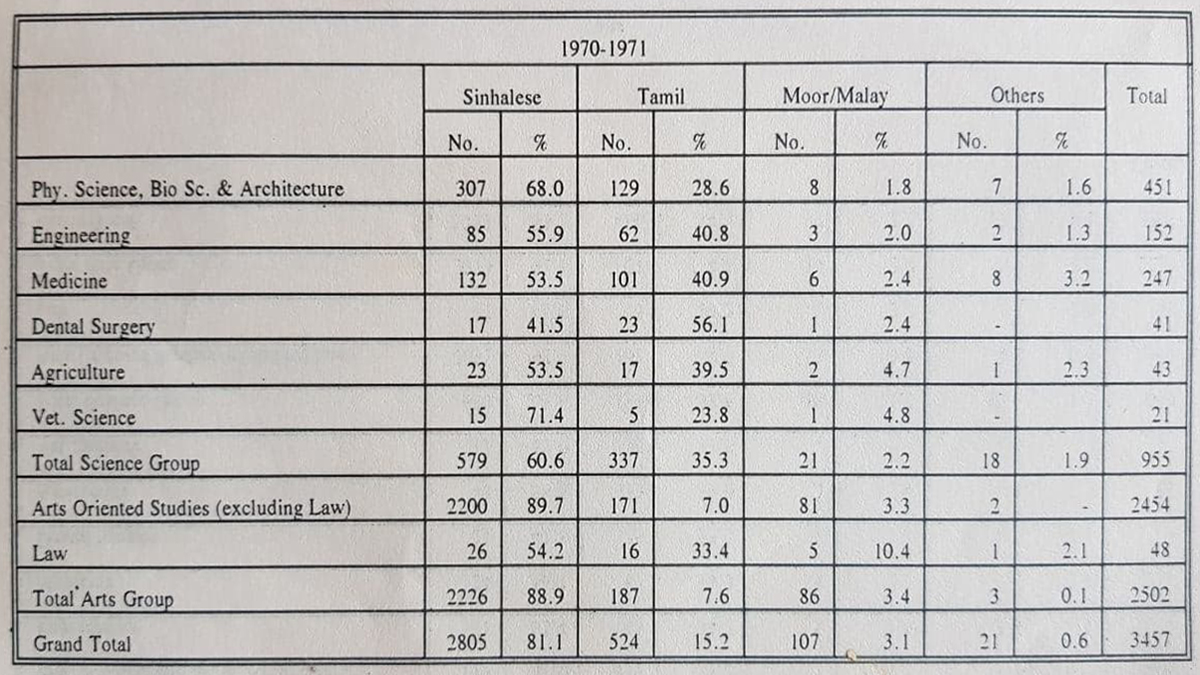

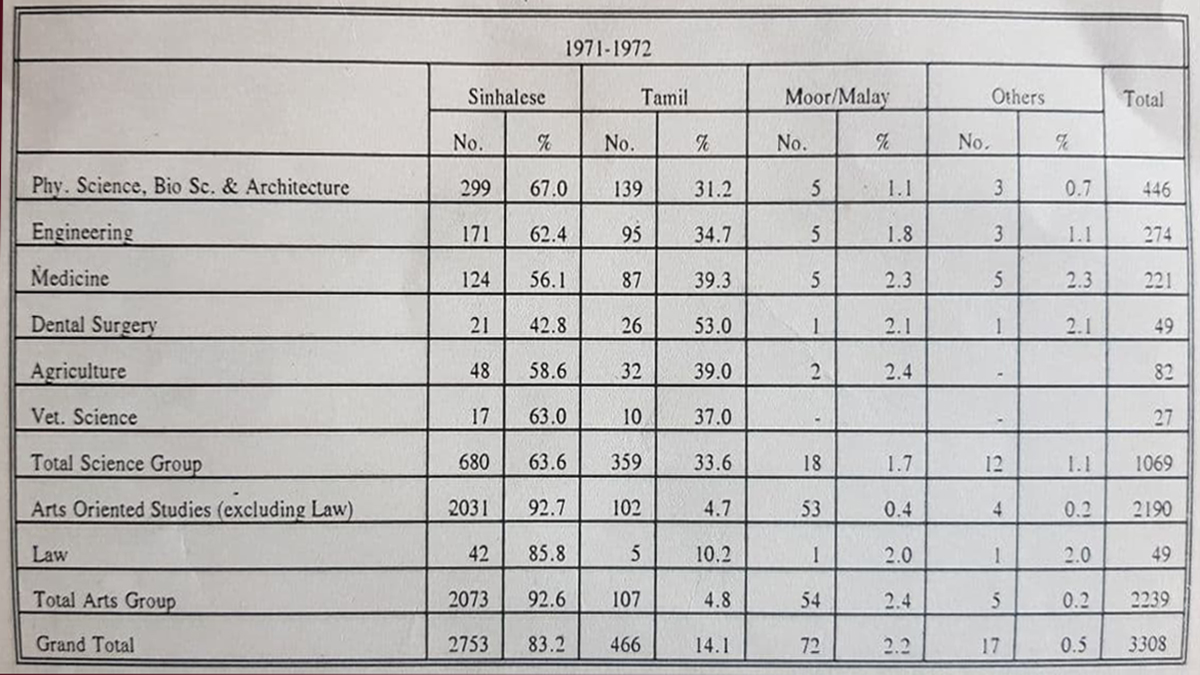

11/ This achieved the goal of increasing the number of Sinhala students gaining admission to science courses, but only somewhat. The Sinhala share of science course admissions from 1970 to 1971 rose 60.6%>63.6%, compared to a corresponding 35.3%>33.6% drop in Tamils.

12/ But this did not satisfy some Sinhala extremists within and outside the govt. It was seen as not providing enough spaces for students from Sinhalese schools in rural areas which continued to lag behind urban areas in enabling entrance to the science-based faculties.

13/ Scheme 2: media-wise standardisation. In 1973, the govt reduced marks in all mediums to a uniform scale so that the final number of qualifying candidates from each medium was proportionate to the number of candidates sitting the exams in that medium.

14/ The justification for this was that the over-performance of Tamil candidates in science (and Sinhala candidates in arts) was attributable to differences in facilities and teaching quality, so ‘standardising’ the marks would correct the imbalances between the two mediums.

15/ This caused far more drastic changes. From 1972 to 1973, the Sinhala share of engineering admissions for e.g. rose 62.4%>73.1% while dropping 34.7%>24.4% for Tamils; the absolute number of Tamils entering science courses fell 359>347 despite total intake rising 1,069>1,177.

16/ But not everyone was content. Kandyan Sinhalese, concentrated in provinces accounting for 47% of the population, made up only 19% of science admissions in 1973, even with standardisation. Moors/Malays also saw themselves as comparatively poorly represented at universities.

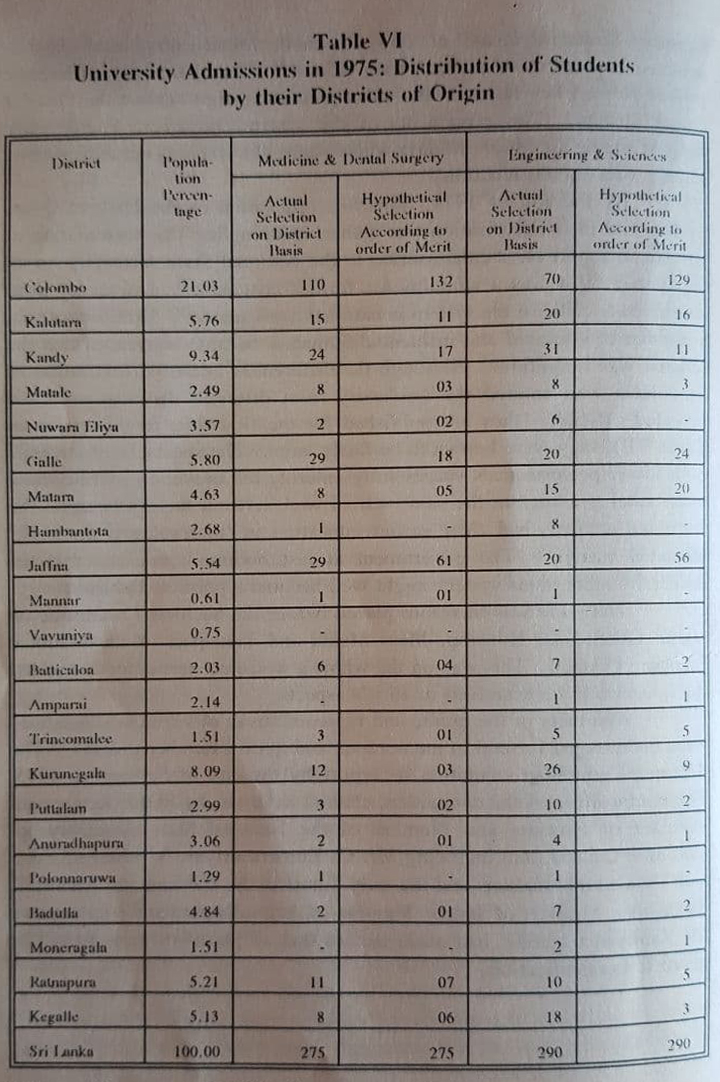

17/ Scheme 3: standardisation + district quotas. To address geographical disparities, the govt in 1974 fixed quotas of places for each district according to population to be filled by qualified candidates. Any remaining places were proportionally distributed among other districts

18/ Standardisation + district quotas severely impacted SL Tamils, who were mostly concentrated in the Jaffna District, entitled to only 5.54% of places. From 1970 to 1974, Tamil admissions to engineering fell 48.3%>16.3%; to medicine 48%>26.2%; & to science overall 35.5%>20.9%.

19/ By this point, opposition to the admissions scheme was widespread. Because district quotas were determined by birth, not residence, students with lower performances were entering university over higher-performing students, sometimes from the same school.

20/ A Sectoral Committee in Parliament recommended ending media-wise standardisation and modifying the district quota system to take into account marks again. The govt undertook to implement only the latter.

21/ Scheme 4: standardisation + modified district quotas. Under the revised scheme in 1976, 70% of admissions were based on ‘raw marks’ and 30% on the district basis, of which half or 15% was reserved for ‘educationally backward areas’.

22/ The new scheme reversed some disadvantages to Tamils, with science admissions rising by 35% from 1975 to 1976 & total university admissions rising to 25% (though this was far from pre-1970 levels). But this satisfied neither Tamil political groups nor Sinhala extremists.

23/ Eventually, the UNP govt elected in 1977 abolished standardisation, though it retained the district quota system through a series of complicated formulae from 1978-1981 to correct for removing standardisation then to further adjust for ‘underprivileged’ districts.

24/ But the changes came too late. An entire generation of Tamil youth had been denied fair opportunity to access university. This worsened the effects of the Sinhala Only Act which had already drastically reduced the number of public service jobs available to Tamils.

25/ Tamil political mobilisation in the 1970s, both electorally and in the nascent militancy, became strongly organised around standardisation. It was one of the major causes of the escalation of conflict.

26/ In the 1980s, the start of the war, the second JVP insurrection and the open economy would all gut the public university system. Sri Lanka is still living its effects.

27/ Finally, standardisation showed the tendency of the #lka govt to A) be guided by Sinhala extremism in areas of public policy, & B) implement quick fixes (standardisation) for structural problems (regional disparities in schooling) with lasting consequences (ethnic conflict).

28/ Even where the policies had good motives & micro-outcomes, the overall effects were disastrous e.g. the district quota’s birth requirement increased admissions of Muslim students from Eastern/North-Western districts, but this provoked anti-Muslim riots in the mid-1970s.

29/29 Note: the ethnic categories used here are those used in the Census of Ceylon 1963 and 1971. But they also show how the categories of ‘Sinhala’, ‘Tamil’ and ‘Muslim’ have never been as fixed as they seem today.

Sources:

–C.R. de Silva. (1979). ‘The Impact of Nationalism on Education: The Schools Take-over (1961) and the University Admissions Crisis, 1970-1975” in Collective Identities, Nationalisms and Protest in Modern Sri Lanka, Marga Institute. [esp. tables.]

–C.R. de Silva. (1979). ‘The Impact of Nationalism on Education: The Schools Take-over (1961) and the University Admissions Crisis, 1970-1975” in Collective Identities, Nationalisms and Protest in Modern Sri Lanka, Marga Institute. [esp. tables.]

–Chelvadurai Manogaran. (1987). Ethnic conflict and reconciliation in Sri Lanka, University of Hawaii Press.

–Nira Wickramasinghe. (2012). “Democracy and entitlements in Sri Lanka: The 1970s crisis over university admission.” South Asian History and Culture, 3(1), pp. 81–96.

–Nira Wickramasinghe. (2012). “Democracy and entitlements in Sri Lanka: The 1970s crisis over university admission.” South Asian History and Culture, 3(1), pp. 81–96.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter