Okay so at the request of @LumberTrading, we& #39;re going to talk about why mortgage-backed securities are a rate product, and what that means. Apologies, this will be long. https://twitter.com/LumberTrading/status/1387488620865413121">https://twitter.com/LumberTra...

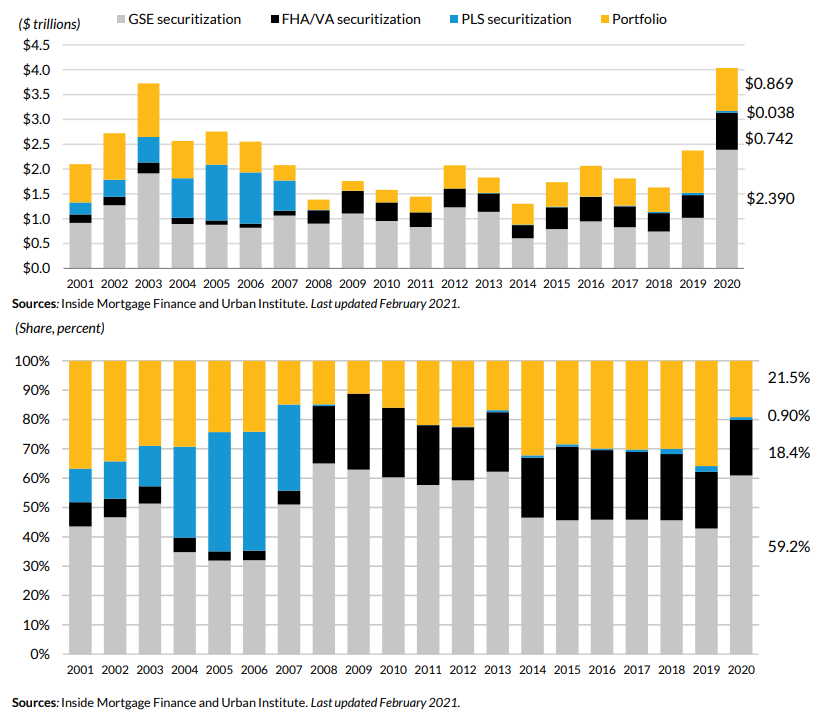

When you borrow to purchase a home, the lender has basically two options: hold the mortgage ("portfolio") or sell it. If selling, there are two further options: sell to one of the government-sponsored entities or gov& #39;t (GSE & FHA/VA securitizations), or someone else (PLS).

As shown, the majority of loans get sold either to the government or the GSEs (Fannie/Freddie) these days. When that happens, the GSEs/government then sell the rights to their cashflows to investors. These are "agency mortgage-backed securities".

Agency MBS have no credit risk. Ultimately the federal government (sometimes directly, sometimes via GSEs) guarantees that if a mortgage borrower stops paying, they& #39;ll pay off the loan. Private securitizations or portfolio loans have credit risk; gov& #39;t-backed MBS don& #39;t.

That& #39;s not to say that they don& #39;t carry risk, but importantly that risk is *only* about changes in interest rates. In general, for the simplest and largest share of MBS, lower rates mean more refinancing, higher rates mean less refinancing.

When you& #39;re holding a pool of mortgages and rates drop, the discounted present value of cashflows rises (just like a normal bond; rates down, price up). BUT because of the prepayment option on a mortgage, you don& #39;t get that benefit, because principal starts getting repaid.

That repayment means you don& #39;t get the interest cashflow from that principal in the future. Oops! The opposite happens when rates go up; discounted present value of cashflow down, and fewer prepays, so you get hit on both ends.

This feature is called "negative convexity" and is a straightforward function of consumers having the option to prepay; bond buyers are selling that option to consumers. As a result, investors generally get an above-Treasuries spread in return for taking the prepayment risk.

Obviously, since prepayments are largely a function of interest rate risk, investors can hedge. For instance, as rates drop, MBS investors can buy increasing volumes of Treasuries, offsetting some of the increase in prepayments. And vice-versa.

I& #39;ve discussed this in the past here: https://www.businessinsider.com/mortgage-housing-market-effect-yield-curve-interest-rates-opinion-2019-8

and">https://www.businessinsider.com/mortgage-... you can see a real bond example and walk-through from @NewRiverInvest here: https://twitter.com/NewRiverInvest/status/1388078213654589441">https://twitter.com/NewRiverI...

and">https://www.businessinsider.com/mortgage-... you can see a real bond example and walk-through from @NewRiverInvest here: https://twitter.com/NewRiverInvest/status/1388078213654589441">https://twitter.com/NewRiverI...

So the key takeaway here is that because of government guarantees, we& #39;ve divorced credit risk from rates risk, and created a pure rates product, but that product has large hedging needs for some end users.

So when the Fed goes out to buy mortgage backed securities guaranteed by the federal government ($40bn per month right now), they are effectively buying Treasuries, but also removing hedging needs from the overall interest rate complex.

The Fed *does not care* if people prepay or don& #39;t, they swallow all that risk and leave it unhedged. Many other investors in agency MBS do as well. But at the margin, they are removing some hedging need by selling an option.

The Fed could have an absolutely equivalent impact on aggregate supply of duration (interest rate risk) and hedging needs if they simply sold options on interest rate futures or swaps. But buying MBS is more convenient and eliminates the need to face a private sector entity.

As far as policy goes, it& #39;s important to keep in mind that buying MBS instead of UST does not directly subsidize mortgage credit provision; it subsidizes aggregate interest rate hedging requirements by removing volatility from the private sector.

That has a positive impact on housing, but only because housing is so interest rate sensitive, NOT because the Fed is directly subsidizing mortgage credit provision.

TLDR: Fed buying MBS reduces risk premiums via removing duration and hedging requirements from private sector balance sheets, but isn& #39;t a direct driver of higher mortgage credit provision and therefore home prices.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter