Since my talk only covered a small part of the answer to the question "What was the city of Rome built with in antiquity?"—let& #39;s see how much of a thread I can get through...

First thing to note: variation through time! Different materials and techniques were used at different times; sometimes the same materials but in different forms.

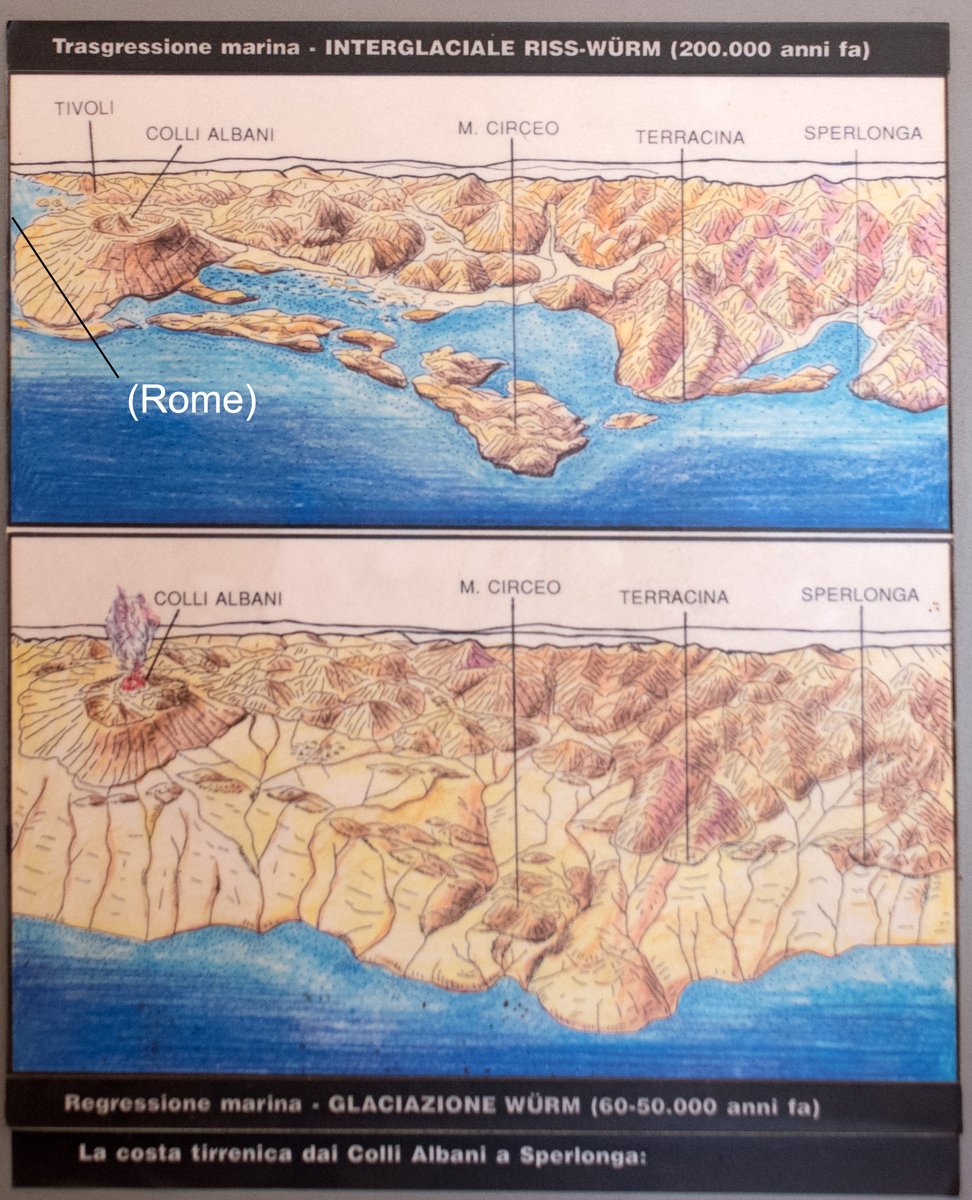

When human species first arrived in the Italian peninsula, the area around Rome didn& #39;t look anything like it does today; in fact, it was underwater. The first Homo sapiens arrived in the region during the Upper Paleolithic about 20,000 years ago, probably using animal hide tents.

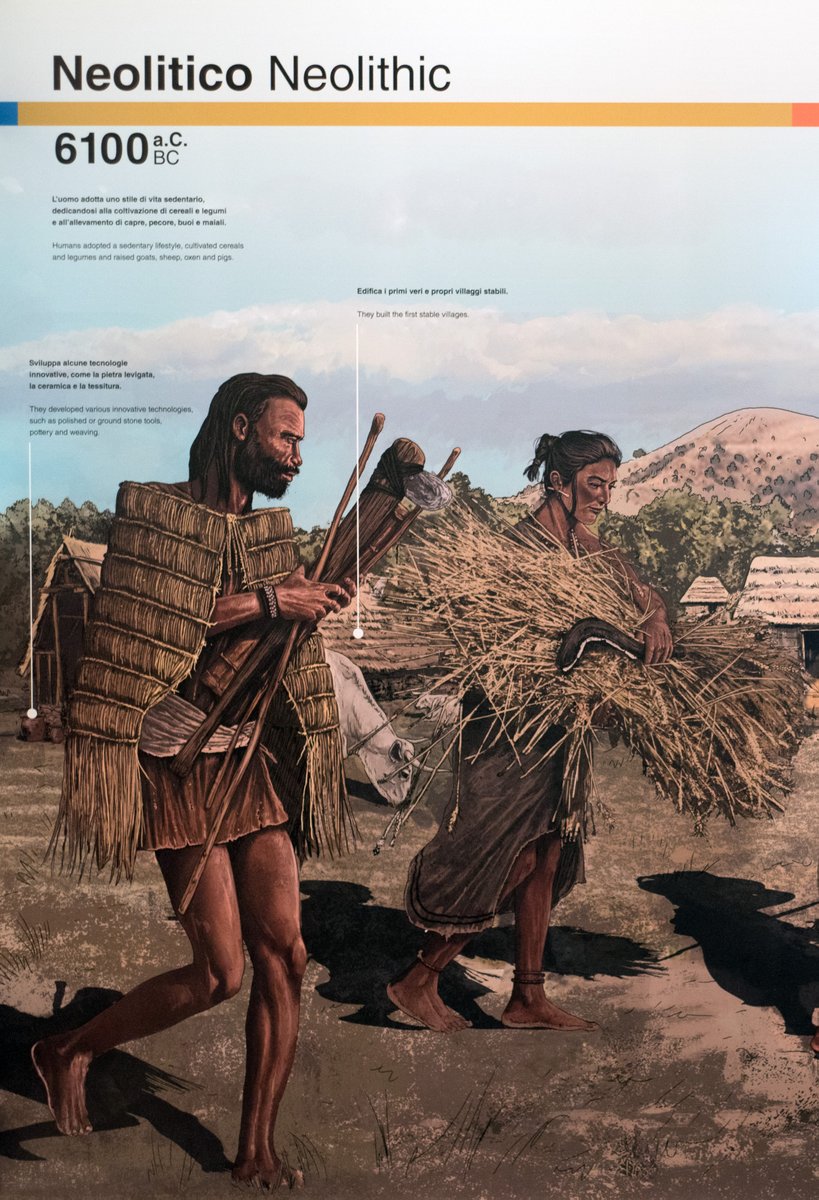

The beginning of the Neolithic period in Italy, during the 6th millennium BCE, witnessed the introduction of more durable structures: huts with timber posts, thatch roofs, and mud walls—though there is as yet no evidence at Rome itself this early. (image @MANNapoli)

Similar hut technology continued through Bronze (ca 2300-1000) & Iron (1000-700 BCE) Ages; terracotta hut urns from near Rome give an idea of what these looked like, while postholes and cuts on Rome& #39;s Palatine Hill (&elsewhere) show their shape & size. (3rd image @ParcoColosseo)

Side note: Romulus didn& #39;t exist (sorry!) but later Romans thought he did, and preserved and repeatedly rebuilt an Iron Age hut on the Palatine that they thought belonged to him.

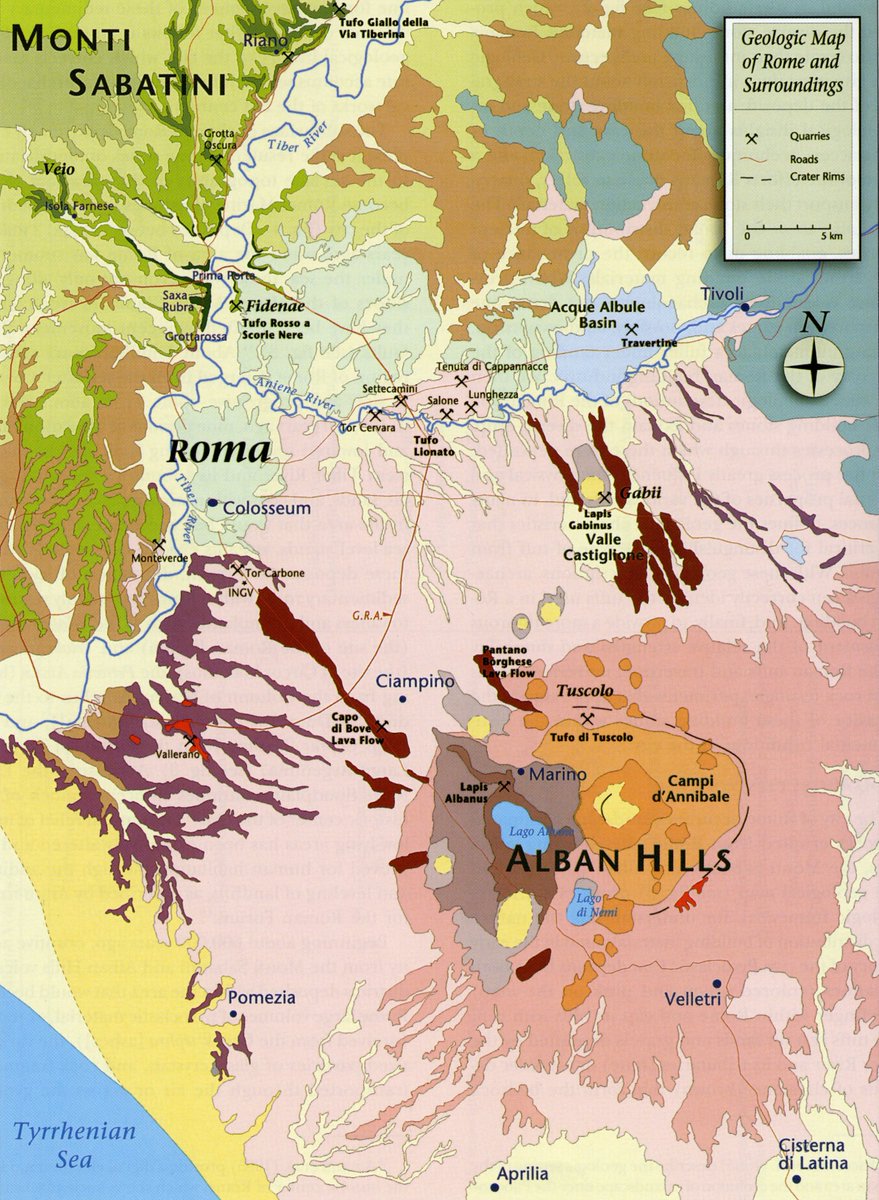

Beginning in the late 8th-7th c. BCE, Romans started using small, unshaped pieces of stone to build foundations; this came from their local bedrock: a series of pyroclastic flows from the nearby Monti Sabatini and Alban Hills volcanoes that became varieties of stone called "tuff"

(first image in previous tweet from Jackson & Marra, "Roman Stone Masonry: Volcanic Foundations of the Ancient City," American Journal of Archaeology 110 (2006), pp. 403-436; second image my photo, samples of Tufo Lionato tuff)

(Another side note: there are a lot of different volcanic tuffs near Rome, around Italy, and around the world; some of the Moai  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🗿" title="Moai" aria-label="Emoji: Moai">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🗿" title="Moai" aria-label="Emoji: Moai"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🗿" title="Moai" aria-label="Emoji: Moai"> of Rapa Nui were carved out of the tuff found on that island. Also the British Museum should return the two Moai that it holds)

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🗿" title="Moai" aria-label="Emoji: Moai"> of Rapa Nui were carved out of the tuff found on that island. Also the British Museum should return the two Moai that it holds)

Over the course of the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, builders in Rome adopted a package of new technologies including fired terracotta rooftiles, rectangular building plans, and squared stone masonry. Clay for the tiles was dug near the Tiber river, and the stone used was local tuff

but not always *very* local; the earliest known temple building in Rome, at the site of Sant& #39;Omobono (early 6th c. BCE) was built with tuff that probably came from a quarry along the Anio river, 6-7 km northeast of the building site, according to research I& #39;ve co-directed

(there was going to be a map showing the distance between Sant& #39;Omobono and the Anio quarries, but it& #39;s been holding up the thread for too long)

Why did the builders of the Archaic temple at S.Omobono go so far afield for stone? We don& #39;t know for sure, but maybe because podium was meant to lift the low-lying temple& #39;s mudbrick superstructure above the reach of the Tiber& #39;s annual flood, and... [out of date image by Ioppolo]

...they quarried the stone from a position along the river, where they could already see that it was resistant to the action of flowing water. Very hypothetical! Maybe closer sources of stone weren& #39;t accessible; maybe the builders owned the area where the quarries were.

The massive foundations of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill, built during the 6th c. BCE, were made with squared blocks of a different kind of tuff, "Tufo del Palatino" (the geological name, though probably not quarried from the Palatine itself).

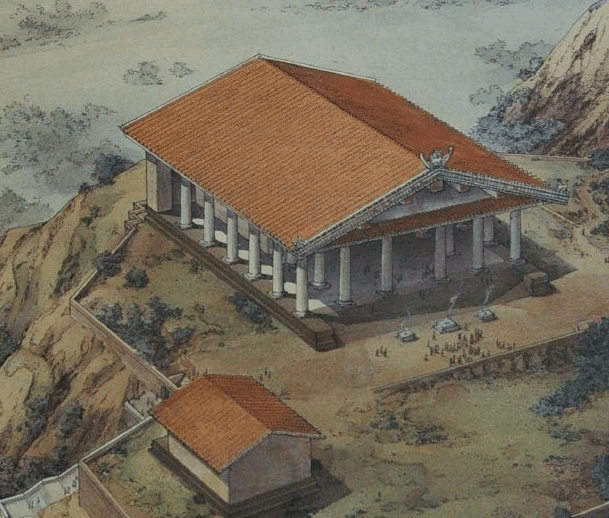

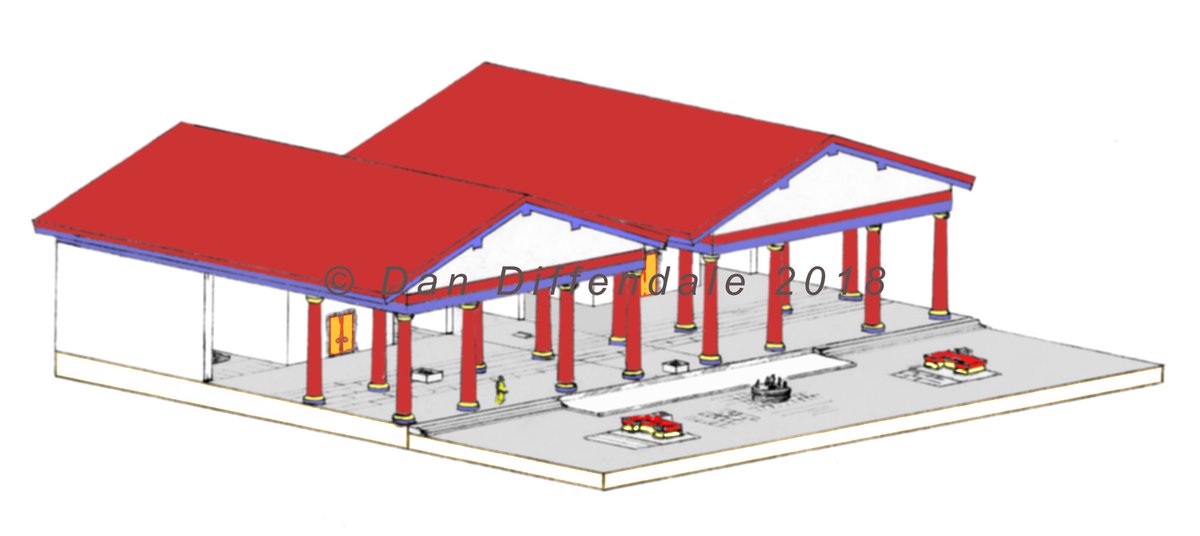

The superstructure of the temple is lost, but was prob. also in tuff; it supported a timber framework to carry the terracotta roof tiles & other decorative elements, which protected both the wood from the weather & the temple from supernatural harms. (recon image Studio Inklink)

Because they don& #39;t survive, it& #39;s easy to miss just how impressive the roof timbers must have been, a feat of structural engineering equal to the foundations, & requiring extremely tall and high quality timber; think of the roof of Notre Dame, roughly the same order of magnitude.

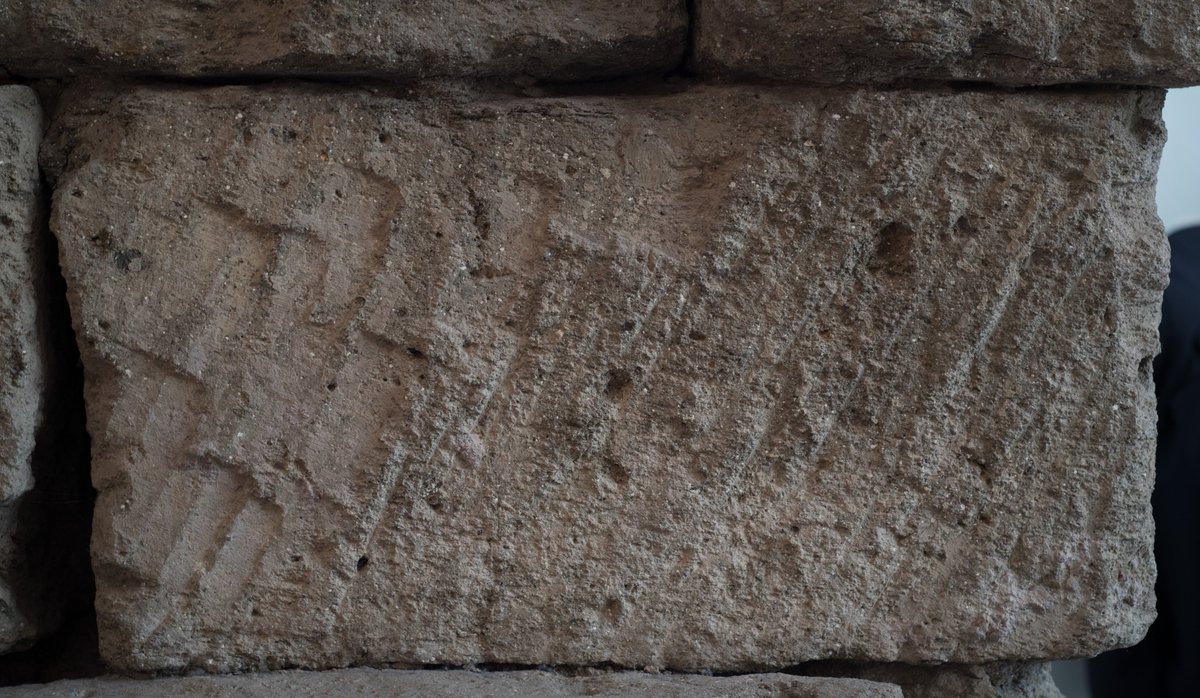

Let& #39;s also pause to consider the vast amount of human labor that went into creating the Temple of Jupiter, and other (smaller) buildings. This block preserves traces of the individual swings of the stonecutter& #39;s hammer as they dressed its surface; each block with six faces...

and on the order of something like 100,000 similar blocks just in the temple& #39;s foundations alone... each block had to be quarried, roughed out, transported to site, dressed, and placed (illustration Studio InkLink)

More tomorrow. I think there& #39;s more to Roman architecture, maybe.

Getting some more of the thread together; in the meantime, if you& #39;re interested in learning more about the Temple of Jupiter and other Archaic Roman monuments, check out @profhopkins & #39;s excellent book _The Genesis of Roman Architecture_!

This basic technology—foundations & walls in squared stone blocks, wooden framework supporting terracotta rooftiles and decorative elements—continued to be used for temples and other public buildings in Rome for many centuries (~6th-1st c. BCE), adding new tuffs and travertine.

[first image in previous tweet: a quick sketch of the later temples at Sant& #39;Omobono in the mid 3rd c. BCE I did a few years ago, with gaudy paint just to give a sense of it; second image, remains of two of the Roman Republican temples at Largo Argentina]

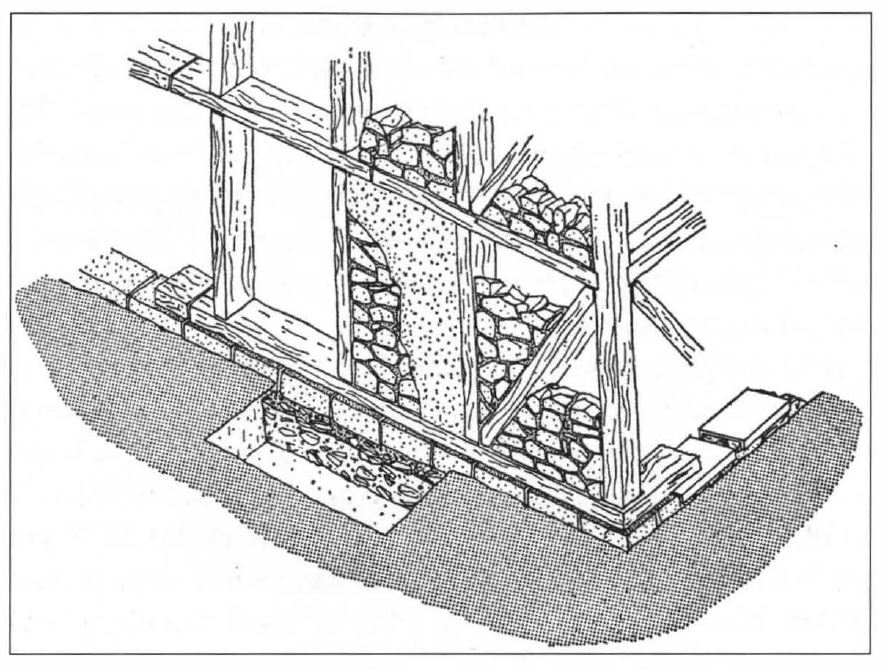

What about houses and other non-public buildings at Rome in this period (ca 6th-2nd c. BCE)? Some had foundations of cut or unshaped tuff, supporting walls of mudbrick or stones set in clay with timber framing, and again wooden roofs with terracotta tiles.

[First image in previous tweet: wooden model of 1st phase of the "Auditorium" site in Rome, a small farmhouse from the later 6th c. BCE; second image, a small modern mudbrick farmhouse in Elis, Greece; third image, Roman timber-frame walls w stone infill, drawing by M. Guaitoli]

Sidenote: you may be familiar with the boast that the Roman historian Suetonius attributes to the emperor Augustus, that he "found Rome a city of brick, but left it of marble"; he wasn& #39;t talking about fired brick, which had scarcely appeared in Rome during his reign, but mudbrick

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

![Why did the builders of the Archaic temple at S.Omobono go so far afield for stone? We don& #39;t know for sure, but maybe because podium was meant to lift the low-lying temple& #39;s mudbrick superstructure above the reach of the Tiber& #39;s annual flood, and... [out of date image by Ioppolo] Why did the builders of the Archaic temple at S.Omobono go so far afield for stone? We don& #39;t know for sure, but maybe because podium was meant to lift the low-lying temple& #39;s mudbrick superstructure above the reach of the Tiber& #39;s annual flood, and... [out of date image by Ioppolo]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/E0KBE2GXsAIuXvu.jpg)