I’m thinking a lot about human remains coverage & what care for the dead can look like in the pursuit of accountability. When I read the news about the MOVE victims, I was horrified. As the shock wore off, I was struck by an element in the coverage: the images.

As an anthropologist, I’ve worked with human remains and surviving communities in post-conflict settings. Ethical considerations there meant following their lead, stepping back, and being transparent with my readers about these encounters.

Now as I study the history of the Morton Crania Collection’s display in Philadelphia history, I’m struck by the relationship between images of the dead and media coverage. The way the dead are presented engages ethics and intent - issues we must apply to MOVE coverage.

In 1985, Philadelphia police dropped a bomb on a house hosting members of MOVE. The ensuing blaze destroyed a city block, left hundreds homeless, and killed eleven people (six adults and five children). Remains of two victims have resurfaced in Penn Museum collections last week.

https://amp.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/apr/22/move-bombing-black-children-bones-philadelphia-princeton-pennsylvania?__twitter_impression=true">https://amp.theguardian.com/us-news/2...

Some publications have elected to share screenshots of the course where the remains in question were handled by Janet Monge. In the images, Monge and her student stand in front of the Morton Crania collection, hands on bones, in some moments laughing or looking at the camera.

The remains from the MOVE bombing were undoubtedly fetishized and objectified in their mishandling by Janet Monge, Alan Mann, and their respective institutions: Penn and Princeton. Are these images not propagating this objectification?

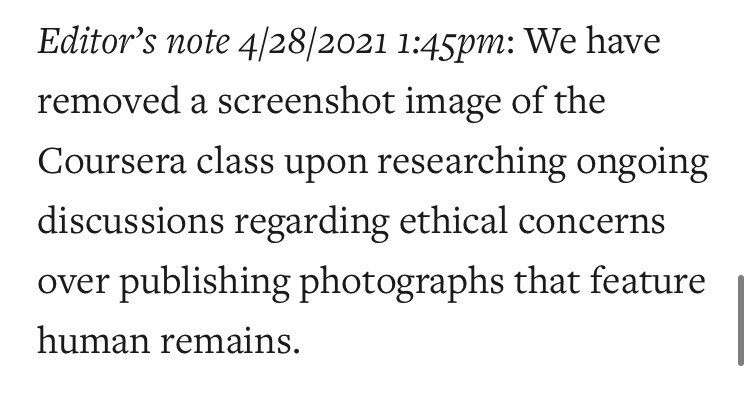

Coursera and Princeton has taken the video down, an acknowledgement of the seriousness of the issue and the nature of the images. Yet despite this, images on Hyperallergic and DemocracyNow! remain up.

There are issues with this, beyond the imperative to share shocking images that have a potential to (re)traumatize readers. There are ethical reasons to avoid sharing images of the dead, particularly those that are being sought after for burial and community care.

Anthropology has had this conversation - has journalism? Working with human remains is an aspect of anthro and while the field is also at the heart of this most recent scandal, there are ethical guidelines that inform many who work with remains.

Sapiens, an anthropological outlet, positions themselves here. Editors cannot move forward with publication without family consent and then go on to consider the age of remains and their context. https://www.sapiens.org/culture/photographing-human-remains/">https://www.sapiens.org/culture/p...

Context is also important. What is the purpose of the course video? What is the purpose of screenshotting and sharing? What does Monge’s hands on the bones say about the remains in that frame? What message does that carry?

These are the questions anthropologists ask themselves in how we write and portray the dead - and these are questions journalists should be engaging.

Journalists can follow NAGPRA’s lead, avoiding the publication of Indigenous remains out of respect for repatriation. University of Tennessee recently created a policy directly addressing images associated with repatriation claims. https://research.utk.edu/ut-unveils-new-nagpra-policy-on-image-use/">https://research.utk.edu/ut-unveil...

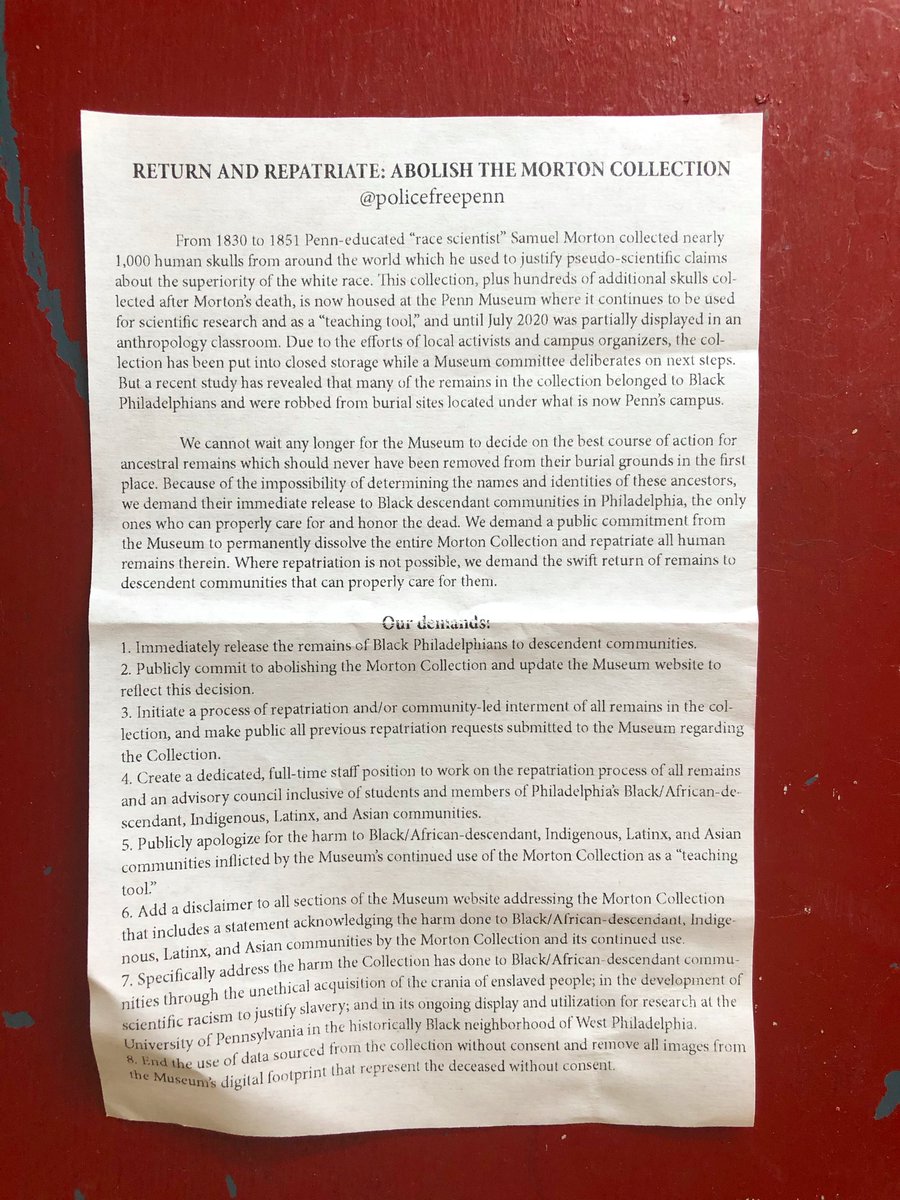

While not in relation to the MOVE remains, Police Free Penn has called for the removal of images of the Morton Collection, highlighting the significance of images and the violence they represent.

The MOVE remains occupy a similar space of tenuous repatriation, meaning their images should be removed out of respect. If it is really necessary to show images of these (or any) remains, journalists should transparently obtain consent from the family.

Happy to see some publications have taken down the image (thanks @billy_penn) or have forgone its use entirely. Can @hyperallergic @democracynow confirm familial consent in the circulation of images showing human remains?

Thank you @hyperallergic ! https://buff.ly/3nkoGn5 ">https://buff.ly/3nkoGn5&q...  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙌🏻" title="Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙌🏻" title="Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)">

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

" title="Thank you @hyperallergic ! https://buff.ly/3nkoGn5&q... https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙌🏻" title="Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="Thank you @hyperallergic ! https://buff.ly/3nkoGn5&q... https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🙌🏻" title="Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)" aria-label="Emoji: Erhobene Hände (heller Hautton)">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>