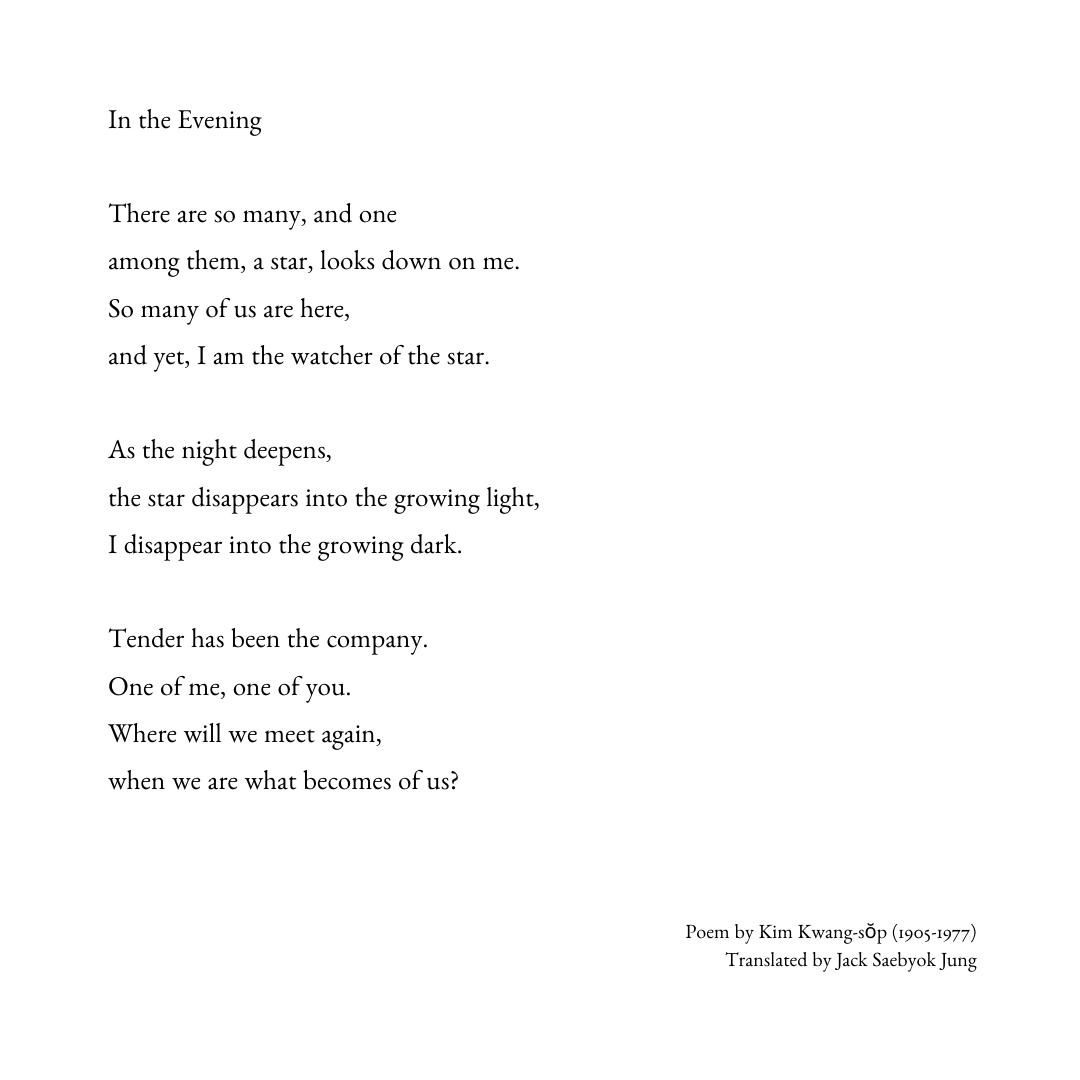

Thank you @freeicecream for this question! I will try to answer in this thread by talking about my translation process for this poem.

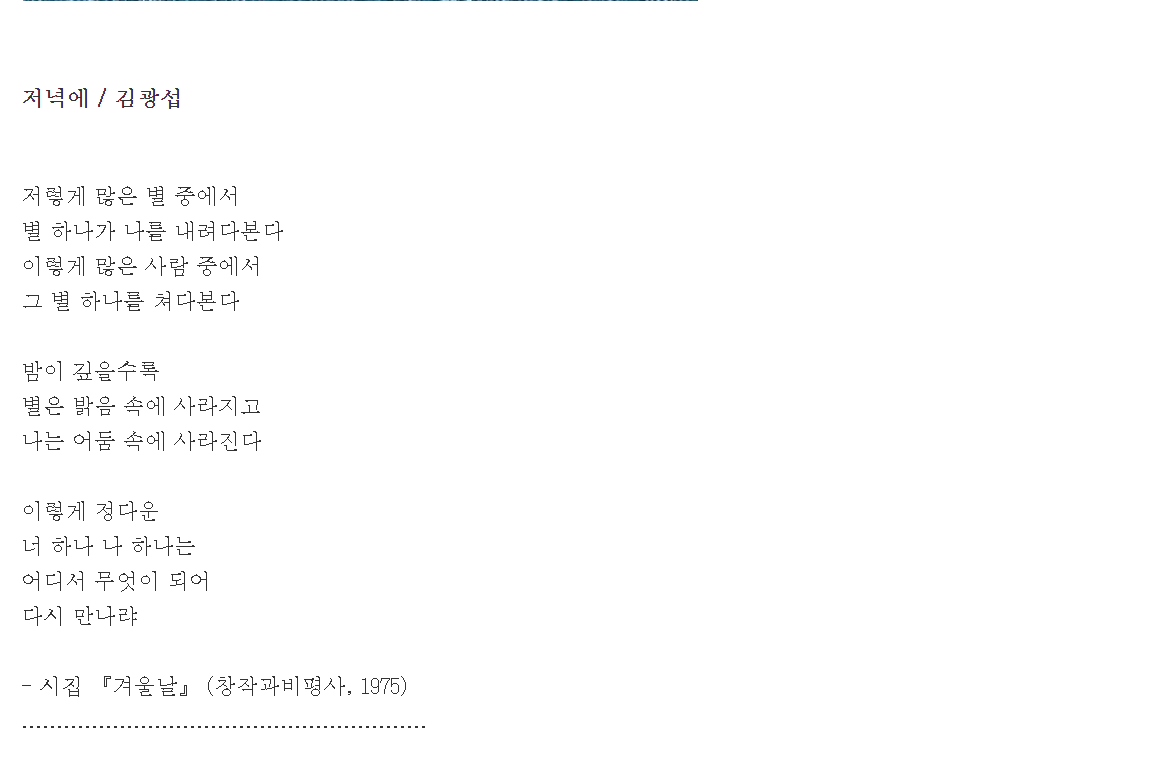

So here is the last stanza in question from "In the Evening" in Korean:

이렇게 정다운

너 하나 나 하나는

어디서 무엇이 되어

다시 만나랴

(1/22) https://twitter.com/freeicecream/status/1387261460926144512">https://twitter.com/freeicecr...

So here is the last stanza in question from "In the Evening" in Korean:

이렇게 정다운

너 하나 나 하나는

어디서 무엇이 되어

다시 만나랴

(1/22) https://twitter.com/freeicecream/status/1387261460926144512">https://twitter.com/freeicecr...

One way to translate these lines would be some like this:

So affectionate

You one I one

Where what will we be

And meet again

And we can also translate it as prose:

We are affectionate, you and I; when we meet again, where will it be and what will we be like?

(2/22)

So affectionate

You one I one

Where what will we be

And meet again

And we can also translate it as prose:

We are affectionate, you and I; when we meet again, where will it be and what will we be like?

(2/22)

The first issue for me to deal with was 정다운 (jeongdawoon). Dictionaries usually translate it as "affectionate, loving, love, close, warm, friendly." These are all wonderful words, but I think most Korean speakers would agree that 정 (jeong) is a special word.

(3/22)

(3/22)

"Affectionate" and "friendly" describe a certain state of being or relationship. "They are affectionate" or "they are friendly" for instance. But these words do not tell us how or in what way such people are to earn the right to be described so.

(4/22)

(4/22)

So "affectionate" and "friendly" to me creates an unnecessary middleman between the reader and the immediate experience. Certain Korean word like "정다운" (jeongdawoon), to me, feel very much like the thing itself, the experience itself.

(5/22)

(5/22)

There are other choices like "love" and "close" and "warm," but "love" implied romance too strongly; "close" felt oddly physical to use between star and its watcher; "warm" seemingly betrayed the gentle coldness of this poem& #39;s beautifully rendered evening sky.

(6/22)

(6/22)

What, then, is the experience itself I mentioned? In Kim Kwang-sop& #39;s poem, there is a soft modulation between thinking of intimacy between two beings (star and its watcher) as part of larger and perhaps indifferent world (starry night sky).

(7/22)

(7/22)

The way this modulation occurs, and you probably already noticed in the original, is how the original poem& #39;s music (some would say its sonic quality) becomes more and more formally intricate in each stanza.

(8/22)

(8/22)

The first stanza reads like a prose in Korean. Of course, two sentences that form this stanza mirror each other in structure and image, but that fact is almost obscured by how matter-of-fact its tone is. Kind of like, "this and that"

(9/22)

(9/22)

The second stanza clearly foregrounds that mirroring with its syllabic meter. 2-4, 2-4-4, 2-4-4. The second are same sentences with key words switched. "별" (star) to "나" (I) and "밝음" (light) to "어둠" (dark). Their pairing is also typographically striking.

(10/22)

(10/22)

Still, having pointed out all these technical brilliance, I would say that the lines of the poem up until this point does not deviate so much from gently rhythmic prose writing that you would see in essays and fiction. Or kind of like blank verse, so to speak.

(11/22)

(11/22)

Suddenly, the last stanza sings. The syllabic meter is 3-3, 3-4, 3-3-2, 2-3. Constant 3 syllabic beats are comparable to English& #39;s trochaic tetrameter. Rapid and very close to song lyrics in their musicality. The poem has moved from prose observation to lyric excess.

(12/22)

(12/22)

While all this musical pyrotechnics is happening, the poem& #39;s sequence of imagery continues from recognition of the star and its watcher (1st stanza), to their disappearance into the night (2nd stanza), finally to an longing for future (3rd stanza).

(13/22)

(13/22)

In fact, the third stanza does not have an image in it. It is a statement of longing. At the same time, the stanza is the most musical out of the three. The sublime beauty of the stars and the night sky and its watcher have turned into a song by the end of this poem.

(14/22)

(14/22)

So, I think we have two important things that we need to work out in the translation of the last stanza: the key word of 정다운 (jeongdawoon) and the music of these last four lines. For 정다운, I remembered the sound of Keats& #39; famous line, "Tender is the night."

(15/22)

(15/22)

I didn& #39;t choose "Tender" to make the allusion to Keats, though I think this poem and "Ode to Nightingale" share a similar spirit. Also, "tender" may have similar issues as choices of "love" and "affectionate" I have mentioned. But I chose it because of its music.

(16/22)

(16/22)

I wanted the line start with a stressed syllable (TENder), then let the line& #39;s rhythm fall off softly through "has been the" until it pick up again in "COMpany." I wanted to prioritize imitating the music by using what& #39;s possible in English.

(17/22)

(17/22)

I also made a choice of interpreting the disappearance of the star and its watcher as now something that has happened in the past when the third stanza begins (has been). This was to clearly show that the last stanza is pointing toward the future.

(18/22)

(18/22)

I choose "tender" also because it implies both abstract intimacy and some aspect of physical bodies. I added "company" to amplify that action of the poem between two beings and also between the world and those two beings.

(19/22)

(19/22)

The rest of these final lines followed similar thought process. And in some of them I tried to imitate 3-3, 3-4 beat syllabic feet from the original rather directly.

(20/22)

(20/22)

For the last two lines, I put "Where" first because that is how it is in the original and that emphasis on location I think is important. I changed the word order in the following lines to accommodate this choice while making sure they sang their music like the original.

(21/22)

(21/22)

So, well, ah, whoo, boy, that is a long answer to your question. I hope this didn& #39;t make the poetry translation process more obscure! In short, I wanted the English version of the poem to slip into lyrical ecstasy of its music in imitation of the original piece.

(22/22)

(22/22)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter