It is a great tragedy that movies like #SixMinutesToMidnight still get made, mainly because there are many more worthwhile, important and fascinating stories to be told about WWII, set in the dark forests and deep valleys of a terrible world far from The Little Island Kingdom.

Thirteen hours later and I’m still seething at the way this cardboard-cut-out, shitely-scripted rush job not only jeopardised my love for Eddie Izzard and Judi Dench, but also took a potentially powerful story and reduced it to a panto version of Murder at Hollycock Manor.

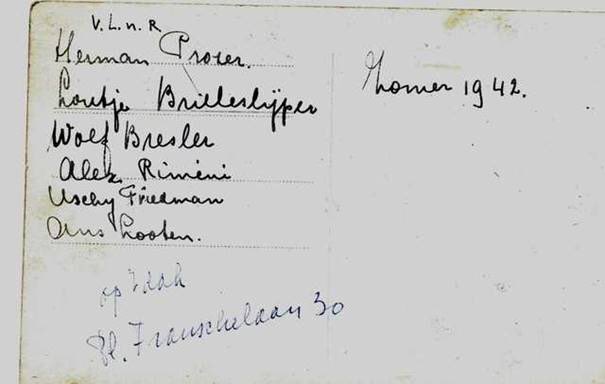

Here’s a story set in the summer of 1942. The fact that you’re looking at this intimate snapshot of six teenagers, basking on a flat roof in Amsterdam, means at least one of them survived the war and saved the picture.

Their names are listed on the back of the photo, as is the address. The house still exists. Amsterdam’s architecture survived the war relatively unscathed, in contrast to its Jewish community. Perhaps the current residents are unaware that history lives on their roof.

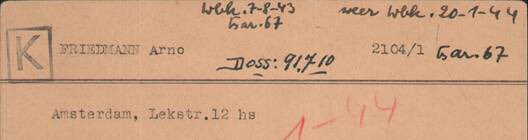

The Restless Hatter | Lekstraat 12 – ground floor | #Unforgotten

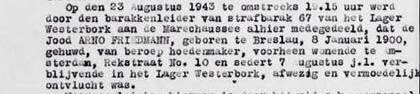

This story might have gone untold were it not that the report of Arno Friedmann’s escape from Westerbork stated that he resided in the “Rekstraat” in Amsterdam, prompting a deeper dive into the archives.

This story might have gone untold were it not that the report of Arno Friedmann’s escape from Westerbork stated that he resided in the “Rekstraat” in Amsterdam, prompting a deeper dive into the archives.

It is unclear how long Arno Friedmann lived at Lekstraat 12, but it was his last official address in Amsterdam, as registered in April 1941. He subsequently went into hiding, which is why he ended up in Penal Barrack No. 67 at Westerbork in August 1943.

Arno Friedmann was always on the move. Born in Breslau in 1900, he was divorced in Dresden in 1937, moving to Paris soon thereafter, before ending up in Amsterdam, where he changed addresses four times and was eventually reunited with his only daughter, Ursula.

The city of Breslau (currently Wroclaw) changed nationality several times as the tides of history pushed the German-Polish border back and forth across Silesia. A member of the Hanseatic League, Breslau was Germany’s third-largest city in 1871, after Berlin and Hamburg.

Even in the middle ages, Breslau had a large Jewish community, which maintained strong ties with Jewish communities elsewhere in Eastern Europe. Tumultuous industrialisation caused the city’s population to grow fivefold to half a million citizens in the 19th century.

Arno Friedmann married Käthe Warczawski in Breslau in the spring of 1924. Their only daughter, Ursula (Uschy), was born in Breslau on January 1925. The family subsequently moved further and further west, possibly after Hitler’s Nazi party rose to power in 1933.

Arno and Käthe were divorced in Dresden on 30 July 1937. It is likely that Arno was by then already travelling back and forth between Dresden, Paris and Amsterdam, registering as a tenant at Reguliersgracht 17 in Amsterdam on 24 February 1937.

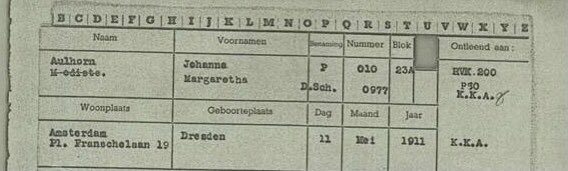

On that same date, Margarete Johanna Aulhorn, registered at the very same address, She too arrived from Paris and she too was a hat designer. Born in Dresden in May 1911, Margarete was eleven years younger than Arno. The couple weren’t married, but were evidently partners.

Ursula Friedmann (then 14) moved in with her father and his partner on 9 August 1939, shortly before German forces invaded Poland from the west and Soviet forces rolled in from the east, dividing the country between them as stipulated in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Soon after Uschy arrived in Amsterdam, they moved to Plantage Franschelaan 19, opening a boutique for ladies’ hats on the ground floor and registering as tenants of the second-floor apartment on 13 September 1939. The war caught up with them soon thereafter.

Records show that Arno moved to Nieuwe Spiegelstraat 37 in July 1940, shortly after German forces rolled into Amsterdam. Uschy remained registered with Margarete Aulhorn on the Plantage Franschelaan, possibly because she was attending a nearby school.

Uschy evidently made friends in the neighbourhood, with whom she is captured in a hauntingly intimate group photo taken by her friend Lyia Landau, who lived across the road at Plantage Franschelaan 30, which had a flat roof where the teenagers could sit out in the sun.

Lyia wrote the names of her friends on the back of the photo. The four lads all have bronzed faces. Were they hiding in the attic rooms in the background? Are they clustered close together to stay out of sight? And had the girls put on their bathing suits downstairs?

The four lads all have bronzed faces and there are four deckchairs. Were they hiding in the attic rooms that are visible in the background? Had they huddled together for the photo or did they want to stay out of sight? And why had the girls put on their bathing suits?

What brought the kids together? They look like friends. Did they all live nearby? Were they the cool kids from a single school class? Were there family ties? The archives answered some of these questions, as we unravelled the story of this unique and intimate photo.

An initial search suggested that the kids were all born in 1925 or 1926. Had they all ended up in one class at the Jewish Lyceum, which the Jewish Council had hastily opened in Amsterdam when the Nazis banned Jewish children from attending public schools in the summer of 1941?

Because Jewish schools weren’t always available outside Amsterdam, parents had to make arrangements for their school-going children. Most of the kids in the photo came from outside Amsterdam and even the Netherlands, but was this what had forged a bond between them?

Let’s start with Herman Prozer, on the left, who was apparently already working as a furniture maker at the age of 16. His father was born in Russia and had come to Amsterdam from Frankfurt-am-Main in Germany in 1920, possibly fleeing persecution in the east.

Lajzer Prozer met his future wife Sara Soesan in Amsterdam. They were married in January 1925 and in October of that year they welcomed their only child, Herman. During the war, Lajzer Prozer worked for the Jewish Council’s food supply department in the city centre.

This job may have sealed Herman’s fate, because his father will have paid heed to the Jewish Council’s instruction to follow the Nazi decree of 26 June 1942 that all Jewish men between the ages of 16 and 40 should report for deportation to Jewish “labour camps” in Germany.

Herman’s pensive expression in the photo suggests that he may already have been aware of his imminent deportation. Records show that Herman arrived in Westerbork on 27 July 1942 and was deported to Auschwitz four days later, perishing at the camp on 30 September 1942.

It is unknown whether Herman’s parents were aware of their son’s fate, but police records show that his father was robbed at gunpoint in their home on 7 February 1943 by a drunken, German-speaking man, who claimed to work for the German security police in The Hague.

By that time, Herman’s mother had already been deported to Westerbork, where she was registered on 28 November 1942. She was reunited with her husband at Westerbork on 26 May 1943 and they were deported to the Sobibor extermination camp together on 1 June 1943.

Second from left in the photo is Louis (Loutje) Brilleslijper, who had moved back to Amsterdam with his parents from Zaandam in May 1942, briefly staying with his grandparents before moving in at Plantage Franschelaan 15, across the road from the Landaus at No. 30.

The Brilleslijpers rented space from the widow Aleida Sajet-Hamburger and her son Jaap, who was actively involved in the resistance group Vrije Groep Amsterdam (Free Group Amsterdam), which provided Jewish people in hiding with food stamps and fake identity documents.

It is unclear whether the Brilleslijpers were also involved in resistance, but Loutje’s father Lion, a tailor, was well aware of the threat he face, as expressed in a piece he wrote to mark the 75th anniversary of the synagogue on the Gedempte Gracht in Zaandam in January 1940.

“This is a deeply tragic age, particularly for Judaism. […] But one of the few oases in this desert of enmity is our beloved Netherlands. May you celebrate the 100th anniversary of this synagogue under better circumstances than those currently prevailing the world.”

Records show that Loutje Brilleslijper arrived in Westerbork on 27 May 1943. He was deported to Sobibor with his parents on 8 June 1943, together with more than 3000 other people, including 1750 mothers with toddlers and other “non-productive” prisoners from Camp Vught.

Touched by the plight of these vulnerable people, some prisoners at Westerbork volunteered to accompany them on the long journey east to Sobibor, where Loutje (17), his mother Lea (48) and father Lion (44) were murdered in the gas chambers almost immediately on arrival.

It is likely that the Brilleslijpers were deported via the nearby Hollandsche Schouwburg theatre on Plantage Middenlaan, which became a gathering point for Jewish deportees. Young children were kept at the crèche across the road, which was the site of acts of great heroism.

Lyia Landau, who took the photo on the roof, was among the nurses who helped sneak children out of the crèche to foster families. She herself survived the war, escaping arrest by sneaking across the flat roof to a neighbour’s attic and rolling herself in a carpet.

But let’s first tell the story of Wolf Bresler, third from left in the photo and looking rather cool in his sunglasses. It is possible that the kids had gathered for his birthday. He turned 17 on 14 July 1942 and is the only person in the photo whose birthday was in summer.

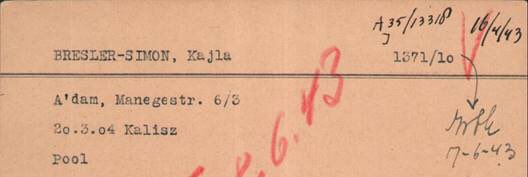

Wolf also came from outside Amsterdam. He was born in Kalisz, Poland, but his family emigrated to the Netherlands in 1930, settling in Didam near Arnhem. The family’s first registered address in Amsterdam was Plantage Franschelaan 30, where the photo was taken.

It is likely that the Breslers spent some time with the Landaus, before moving into their own place on Manegestraat. Evidently, Wolf spent enough time on Plantage Franschestraat to make friends, with whom he may later have attended shared a class at the Jewish Lyceum.

Westerbork records show that Wolf arrived at the transit camp aboard a so-called “S-transport”, where S stands for straf, which means it was a penal transport. He also ended up in Penal Barrack No. 67 at the camp, which means he was probably arrested while in hiding.

This is confirmed by the fact that Wolf’s mother and younger brother also spent time in Camp Vught, which had a stricter security regime than Westerbork, because its inmates included resistance operatives and black market profiteers, as well as Jews captured in hiding.

On 5 June 1943, Vught’s commander Karl Chmielewski ordered all Jewish children out of the camp. He said they would be taken to a special “children’s camp” nearby, but the next day all children aged 0-3, as well as their parents, were deported to Westerbork.

The next day, children aged between 4 and 15 were also deported to Westerbork. Among them were Wolf’s younger brother Fishel (11) and mother Kajla, who arrived at Westerbork on 7 June 1943 and were deported to the Sobibór extermination camp the next day.

Wolf arrived in Westerbork shortly thereafter on 12 June 1943. His father had already been in the transit camp since April, producing rucksacks for prisoners assigned to labour teams. Wolf was placed in Penal Barrack No. 67, but wasn’t immediately deported.

As an apprentice metalworker, Wolf may have been assigned to one of the workshops, perhaps with his father’s assistance. Wolf was deported to Sobibór on 29 June 1943. His father followed three months later on 21 September 1943. Both were murdered on arrival.

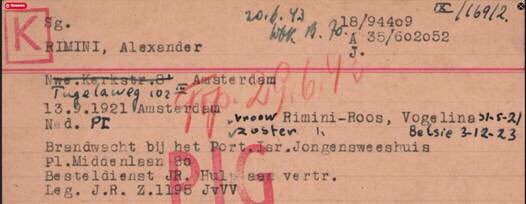

Which brings us to Alex Rimini, on is haunches behind the two deckchairs, who caused some confusion, partly because there were two Alexander Riminis in Amsterdam in 1942, both of whom were in the running to play the role of Alex in roof photo.

To complicate matters, the two Alex Riminis were cousins (born in 1921 and 1926), which meant they might look similar, because their fathers were brothers. There were also two photos of Alex. But is this the same lad at 11 and 16? Or are these two different Alexes?

Alex is the only person in the photo wearing a long-sleeved shirt and tie. Had he dropped in to see his friends after work? Had the onset of puberty and two years of war transformed him from a bashful boy into a slender, young man looking confidently into the camera?

Initially, the younger Alex (born in 1926) seemed to have a clearer link with the kids on the roof, because he was the same age and may have gone to school with them. However, the fact that Alex is wearing a shirt and tie in the photo suggests he was older than the others.

Oddly, the younger Alex also had an elderly look about him, recounts classmate Henry Schogt, who describes him as follows, when they first met at age 13 or 14: “When he entered the classroom, he was very obese and shuffled as if he were wearing slippers…”

“His clothes looked faded and wintry, much too warm for September. But strangest of all was his hair, which gave him the appearance of an old man, although he was only a year older than me. The hair he had left seemed on the verge of breaking off or falling out.”

The fact that Henry Schogt devoted an entire chapter to this friendship with the younger Alex Rimini made it tempting to cast him as the Alex on the roof, because such detailed stories are scarce. But our nagging doubts were amplified as our quest continued.

The elder Alex – who would have been 20 in the roof photo – had much clearer connection with the kids on the roof. He had grown up at Jewish orphanage for boys, across the road from zoo and around the corner from Plantage Franschelaan, where the photo was taken.

In fact, the elder Alex was listed as “fire warden” at the orphanage on his registration card for the Jewish Council, where he worked at the delivery service of the Department of Assistance to Deportees, possibly bringing hampers to Jews ordered to report for deportation.

The Jewish Council published a packing list in September 1942, which included articles such as a water bottle, cup, plate, cutlery, gloves, pyjamas, two blankets, two sets of warm underwear and other warm clothing, preferably packed in a good rucksack, rather than a suitcase.

It is likely that the elder Alex had cause to be in the neighbourhood often, because the Jewish Council also had a “youth hostel” at Plantage Franschelaan 13, which housed young pioneers, mainly Jewish immigrants, who had been preparing for life in Palestine.

The elder Alex would probably also have been active at the Hollandse Schouwburg theatre and at the crèche across the road, where Lyia Landau may already have been working when she took the photo on the roof. Was Alex also involved in finding hiding places for the kids?

Alex lived with his family on Nieuwe Kerkstraat, which is where Lyia Landau’s father and uncle first had their confectionery factory. Alex’s municipal card describes him as a “warehouse employee”. Had he previously been employed at the Landaus’ factory?

Alex’s municipal card also states that he married Vogelina Roos on 31 July 1942. Had Alex been among the young Jewish people who attempted to avoid deportation to labour camps by getting married? Had Alex come to the house to share the news with his friends?

Records show that Alex and his younger brother Hartog Rimini (1924) lived at the same orphanage at Plantage Middenlaan 80. The brothers were 10 and 7 years old when they were placed in the care of the Portuguese-Israelite Boys Orphanage Aby Jetomim (Father of Orphans).

It is likely that the brothers ended up in the orphanage because their mother was unable to take care of them. Jetta Cohen’s first husband Levie Rimini died in March 1929, leaving his wife with three children: Alexander (8), Betsie (6) and Hartog (4).

From the age of 7, Betsie Rimini lived at Nieuwe Prinsengraght 17, which was the Portuguese-Israelite Girls Orphanage Mazon Habanot. It is highly likely that Betsie (then 10 or 11) posed for this photo, which dates from 1934 and mark the 200th anniversary of the orphanage.

Their mother, Jetta Cohen, moved into the first-floor apartment at Nieuwe Kerkstraat 8 in October 1939. A month later, Alex Rimini (then 18) moved in with his mother at the same address. When Betsie Rimini turned 18 in December 1941, she also moved in with them.

Their younger brother, Hartog, was one of just five boys still living at the Aby Jentomim Orphanage in 1941. One of the other orphans, Leo Jacob Nassy, who was the same age as Hartog and probably a close friend, later married Betsie Rimini in Camp Westerbork in 1943.

Alex Rimini married Vogelina Roos in July 1942, around about the time that the photo on the roof was taken. Had Alex come to the house to ask one of the Landau brother’s to be a witness at his wedding? Or perhaps to invite the girls to be bridesmaids or simply to attend?

To answer these questions and others, we went in search of Lyia Landau’s son Tjitte de Vries, who posted the roof photo online. In a recent interview, Tjitte recounted that his grandfather came to Amsterdam from Lübeck in early 1932, when the Nazis rose to power in Germany.

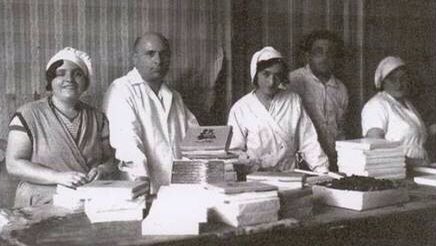

“My grandfather and his brother set up a chocolate and confectionary factory, supplying marzipan figurines, Easter eggs and chocolate truffles to some the city’s biggest retailers. Their business was very successful until it was liquidated by the Germans in 1942.”

“The letters that my grandfather Pinchas sent to his family and neighbours in Amsterdam from Westerbork in 1943, confirm that he loved life and greatly valued friendship. He and my grandmother, Sara, were very hospitable. Their house was always open to all.”

Tjitte’s mother found it difficult to talk about the war. “But she did talk about her youth in Amsterdam: playing football out in the street with the boys or going to the swimming club and playing volleyball. She’d often take her schoolmates to the sugar factory for a treat.”

This immediately suggests that sport was the bonding factor between the friends on the roof. They played football out in the street together. Alex Rimini and the boys from the hostel across the road joined in. The girls were swimmers and felt comfortable wearing bathing suits.

As early as May 1941, Jewish people had already been banned from visiting beaches and swimming pools, but from 12 June 1942 Jews were forbidden to take part in any sporting activities at all. Had the street footballers gone up to the roof after their last game out in the street?

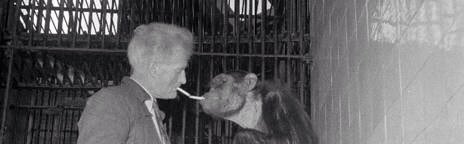

Which brings us to the solidarity of Ansje Looten, on the far right, who is the only non-Jewish person in the photo. Her father was concierge at the nearby zoo, which remained open during the war, but also offered refuge to Jews and others, who hid behind the animal enclosures.

“On most nights, there were dozens of people hiding on the Artis grounds,” writes the zoo’s former director Maarten Frankenhuis. “It’s estimated that around 200 to 300 people stayed here for several days or even weeks and years. No one knew exactly how many.”

“For safety reasons, no one ever openly discussed these things, which is why no one was ever arrested at the zoo. Some people who had hidden at the zoo were amazed to discover, after the war, that a good friend or acquaintance has been camping out in a nearby enclosure.”

Zookeeper J. van Schalkwijk, who served Artis for 52 years, was in charge of the Apenrots enclosure near the entrance, where even today Japanese macaque monkeys live on a large, rock-like structure, which is hollow on the inside and surrounded by a moat.

“During one raid, I let some lads in via the back door. It took them straight to the Monkey Rock, where I laid a plank over the moat, so that they could hide inside the rock. The Germans had no idea there were Jewish people hiding there, because there was water all around.”

Van Schalkwijk also tells of the zoo’s best known refugee, Duif van de Brink, a Jewish woman who stayed at the zoo for four years. “During the day, she mostly sat out on bench by the apes and monkeys, but at night she slept in the service area behind the wolf enclosure.”

“In the mornings, she’d come to the monkey house kitchen to get some breakfast. Then she’d sit out on the bench all day chatting to people, even Germans, who were never aware that she was Jewish. She eventually stayed with us until the end of the war,” recounted Van Schalkwijk.

There is no record of Ansje Looten’s friends ever having sought refuge at the zoo, but it would have provided a perfect hiding place. It is unclear whether her father Gerrit, the zoo’s concierge, was involved in assisting refugees, but most staff were aware of their presence.

After the war, Ansje married Frederik Spangenberg, who regularly spent time in Bagdad, Iraq, in the 1950s and ‘60s. The family’s records are restricted, which suggests that Spangenberg worked in a governmental or corporate sector that required confidentiality.

Which brings us back to Uschy Friedmann, who was 14 when she arrived in Amsterdam in August 1939, moving in with her father Arno and his non-Jewish partner Margarete Aulhorn, who was imprisoned at Camp Vught, suggesting an involvement in resistance activities.

Arno Friedmann’s movements suggest he was well aware of the fate that awaited deported Jews. It is likely that he left Uschy with his Margarete when he went into hiding. Uschy’s presence on the roof suggests she may have been hiding across the road.

Not long after the roof photo was taken, Ursula Friedmann ended up in Camp Westerbork. Her registration card bears the bleak descriptors “unemployed, stateless, unmarried” along with the deportation date scrawled diagonally in red pencil: 15 July 1942.

This date suggests that Uschy had the grotesque misfortune of being part of the first mass deportation out of Westerbork, boarding the train to Auschwitz with 1134 other deportees. Records show that she survived for some time, perishing on 30 September 1942 at the age of 17.

(To be continued...)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter