I will teach Zhuangzi& #39;s views on death. Drawing for ch 24 "Zhuangzi was accompanying a funeral when he passed by the grave of Huizi... he said, "Since you died, Master Hui, I have had no material to work on. There& #39;s no one I can talk to any more." 1/

If we take the text at face value, bracketing for a moment whether Zhuangzi was a historical figure, we see Zhuangzi survives his best friend (Huizi) and his wife. At the end of the Zhuangzi he discusses his own death and funeral with his disciples 2/

And throughout the Zhuangzi are several passages on death that together constitute a coherent vision on death. This vision of death coheres with his ideas on friendship, oneness and suffering. 3/

I saw a standup comedian yesterday who asked "How do you know if you& #39;re middle aged?" - and then answered "You multiply your age by two. If you die at that age, and it& #39;s not a tragedy, then you are middle aged."

This raises the question: is dying old a tragedy? Is dying at all?4/

This raises the question: is dying old a tragedy? Is dying at all?4/

If we bracket questions on the historicity of Zhuangzi and take the text at face value, then the character of Zhuangzi emerges as someone who survived both his best friend (Huizi) and his wife. He also discussed his own impending death with his disciples. We& #39;ll consider these 5/

Zhuangzi has a concern for "living out your years." E.g., ch 3 he discusses a disabled man, Shu, who is "still able to look after himself and finish out the years Heaven gave him".

He speaks in positive terms about Shu& #39;s good life that he lives with his disability 6/

He speaks in positive terms about Shu& #39;s good life that he lives with his disability 6/

Also, Zhuangzi was not particularly concerned with the problem of suffering. He took it for granted that our lives will know some joys and some sorrows. Bodily suffering is just one form of transformation that human and other bodies go through in the course of their existence 7/

It& #39;s part of the dao and should be accepted as such.

E.g.,(ch 6) Master Yu is disabled and "Yet he seemed calm at heart and unconcerned. Dragging himself haltingly to the well, he looked at his reflection and said, "My, my! So the Creator is making me all crookedy like this!" 8/

E.g.,(ch 6) Master Yu is disabled and "Yet he seemed calm at heart and unconcerned. Dragging himself haltingly to the well, he looked at his reflection and said, "My, my! So the Creator is making me all crookedy like this!" 8/

He& #39;s asked if he resents his disability. Master Yu answers

"Why no, what would I resent? If the process continues, perhaps in time he& #39;ll transform my left arm into a rooster. In that case I& #39;ll keep watch on the night. 9/

"Why no, what would I resent? If the process continues, perhaps in time he& #39;ll transform my left arm into a rooster. In that case I& #39;ll keep watch on the night. 9/

Is death then, just one of these transformations of the dao? At several instances, Zhuangzi points out that death is a transformation that we mistake as the end, but that really is just a new phase in the existence of the matter that makes up human and other bodies. 10/

E.g., ch 6

"Suddenly Master Lai grew ill. Gasping and wheezing, he lay at the point of death. His wife and children gathered round in a circle and began to cry. Master Li, who had come to ask how he was, said, "Shoo! Get back! Don& #39;t disturb the process of change!" 11/

"Suddenly Master Lai grew ill. Gasping and wheezing, he lay at the point of death. His wife and children gathered round in a circle and began to cry. Master Li, who had come to ask how he was, said, "Shoo! Get back! Don& #39;t disturb the process of change!" 11/

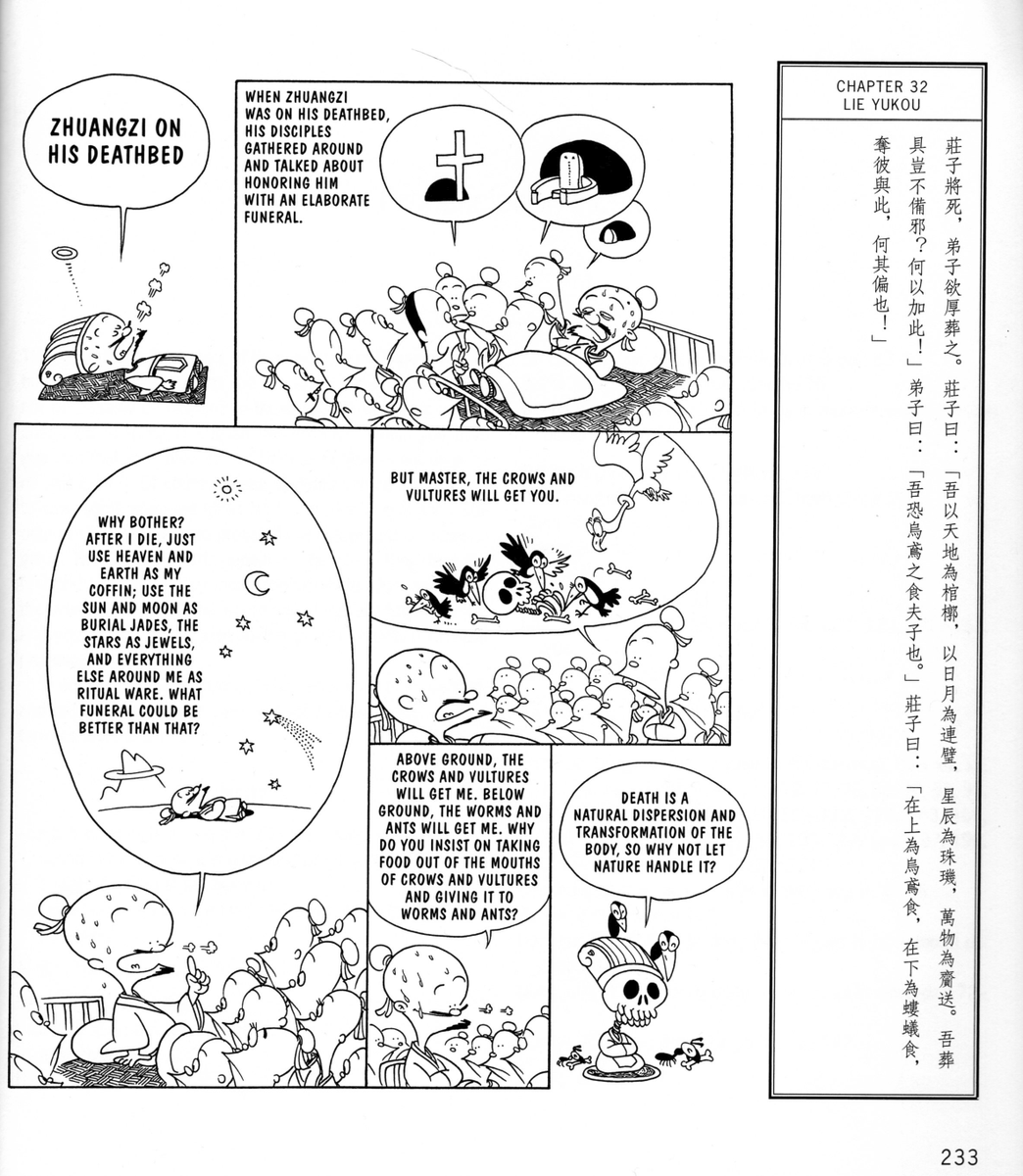

We see this idea of death most notably in Zhuangzi& #39;s description of his own impending death, here brilliantly illustrated by Tsai. Text version here https://ctext.org/dictionary.pl?if=en&id=3011">https://ctext.org/dictionar... 12/

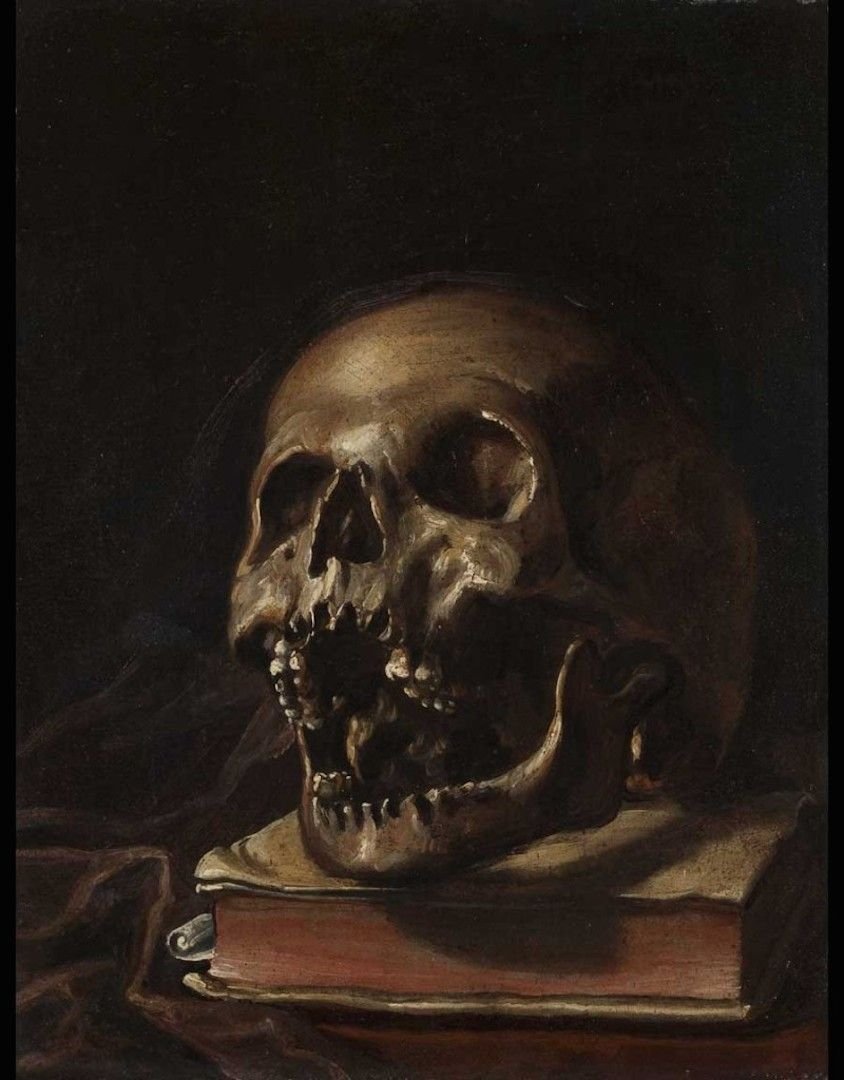

Graham (1989) points out an interesting contrast between Zhuangzi’s concept of death and that of medieval European writers and painters. The latter emphasized its gruesomeness, reminding us of the fate of our souls upon death. 13/

(Fetti, Vanitas, a representative example)

(Fetti, Vanitas, a representative example)

The aim of Zhuangzi, however, is not to shock, but rather, to look at the facts of death, including corruption and decomposition, without horror, so as to be able to calmly face it. The passage on his own burial needs to be read in that context, as subversive 14/

“‘I shall have heaven and earth,’ said he, ‘for my coffin and its shell; the sun and moon for my two round symbols of jade; the stars and constellations for my pearls and jewels; and all things assisting as the mourners. " (ch 32) 15/

In several passages relating to death, the dao is personified as “the maker of all things.” In the Daodejing, the dao is called, “the Mother of the myriad things” (Dao de jing, chapter 1, https://ctext.org/dao-de-jing ).">https://ctext.org/dao-de-ji... Note, this does not make the dào analogous to a theistic god. 16/

Rather, the dào is the originator of all that is, the undifferentiated substance/entity that is prior to the world and its myriad things. Zhuangzi saw our personal brief lives in the bigger picture of the dào, the originator that is always transforming. 17/

Rather than trying to cling to and maintain things the way they are, the Daoist philosopher embraces this change as an inevitable and good feature of reality. In the Butterfly dream (ch 2), Zhuangzi is not too worried about his transformation or about knowing what he is 18/

Realizing that things ultimately transform makes death bearable. After his wife’s death, Zhuangzi is banging a pot (a base form of music not suited for a funeral) and sitting with splayed legs rather than in the respectful mourning position. 19/ https://ctext.org/dictionary.pl?if=en&id=2831">https://ctext.org/dictionar...

Huizi, who came to condole him, is shocked to find Zhuangzi in this way. Z. acknowledges that he grieved like everyone else would in this situation, but later, as he realized the bigger picture, namely that his wife’s death is part of the overall transformations in nature 20/

With the passage on Zhuangzi& #39;s wife comes a worry: if we love and form attachments, we open ourselves to the risk of grief and loss. This is a problem Zhuangzi acknowledges we must deal with, and many philosophers have dealt with it. 21/

One solution is to avoid attachments altogether. If you have no friends, no romantic partners, no spouse, no children, you can’t get hurt by them either. This is what Arthur Schopenhauer recommended. 22/

Inspired by Buddhism (taking its recommendations about detachment to an extreme), Schopenhauer argued that our desires and attachments only bring misery with them: either they remain unfulfilled, in which case we remain unhappy, 23/

Or they are fulfilled, but then we set our sights on something else, and because of that we become miserable again. Schopenhauer recommended not having friends, and not marrying: if you’re single and unattached, then at least other people can’t disappoint or sadden you. 24/

But this solution is hardly realistic. As happiness studies show, friendship is an important predictor of life satisfaction; it fulfills basic needs such as a sense of autonomy, of connectedness, and of competence. We need attachments (Zhuangzi acknowledges this) 25/

Contrary to common misconception, the Stoics did not suggest hedging yourself against prospective loss. Rather, they recommended that we train ourselves to the idea that nothing lasts forever, and that we need to accept that.

What& #39;s Zhuangzi& #39;s solution?

26/

What& #39;s Zhuangzi& #39;s solution?

26/

The solution lies within the metaphysics of Daoism, according to @alexismelder https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/sjp.12086?casa_token=Z7qtUxcvAAwAAAAA%3AGEl9tiXXv3uDgMUAc0UqHKUgGPkOou2KAZHOtcu-bbgdDZEfRTJ_POpTEbD5OCYk2da2g3WX0rKY

The">https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/... Zhuangzi presents death as a change and not a loss, and this allows a Zhuangzian daoist to enjoy the goods of friendship and finding peace in the transcience of things 27/

The">https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/... Zhuangzi presents death as a change and not a loss, and this allows a Zhuangzian daoist to enjoy the goods of friendship and finding peace in the transcience of things 27/

"Although it might still seem odd to think that a dead person still exists, even after being scattered throughout a multitude of diverse forms, and thus still capable of being valued, there are theoretical advantages that may make it worth the cost" says Elder 28/

The passage of four friends in ch 6 can illustrate this

"How marvelous the Creator is! What is he going to make of you next? Where is he going to send you? Will he make you into a rat& #39;s liver? Will he make you into a bug& #39;s arm?" 29/ https://ctext.org/dictionary.pl?if=en&id=2756">https://ctext.org/dictionar...

"How marvelous the Creator is! What is he going to make of you next? Where is he going to send you? Will he make you into a rat& #39;s liver? Will he make you into a bug& #39;s arm?" 29/ https://ctext.org/dictionary.pl?if=en&id=2756">https://ctext.org/dictionar...

Lai is told to stick to his values in the face of death.

"For a person to value life but resist death would be a perversion of our very nature,"

Thus, we can see how friendship can be valuable, how attachments are important, Zhuangzi also offers space for personal grief 30/

"For a person to value life but resist death would be a perversion of our very nature,"

Thus, we can see how friendship can be valuable, how attachments are important, Zhuangzi also offers space for personal grief 30/

But ultimately, death is part of the transformation of things, it& #39;s a natural process, even if our consciousness does not survive it, it is not to be regretted /end

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter