While many of my tweets about #JapaneseMythology this semester have focused on the ways myths support nationalist and imperialist projects, some post-war authors and artists have retold myths to subvert dominant hierarchies. A  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">1/18

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">1/18

Take Tezuka Osamu’s magnum opus Phoenix, which was started in the 1950s and alternates between futuristic and historical stories. He& #39;s explicit about his sources from Japanese myth and his project to highlight Yamato aggression and search for an alternate history. 2/18

The first volume, "Dawn" sets the tale in the time of the historical Himiko, a third-century queen, but populates the broader world with humanized gods from the Kojiki/Nihon shoki myths such as Susano’o, Sarutahiko, Uzume, and others. 3/18 https://www.viz.com/read/manga/phoenix-volume-1/product/26">https://www.viz.com/read/mang...

But it uses these mythical characters to show the ruler (and deities) as decidedly human, self-centered, and fallible. For example, he redraws the famous scene of Amaterasu and the Heavenly Rock Cave to have Himiko running away to save herself rather than her people. 4/18

As Mark MacWilliams writes more generally of the volume, “Tezuka relentlessly deconstructs the sacrosanct mythic histories of the Japanese emperor as a living god.” 5/18 https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/G/bo70073134.html">https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books...

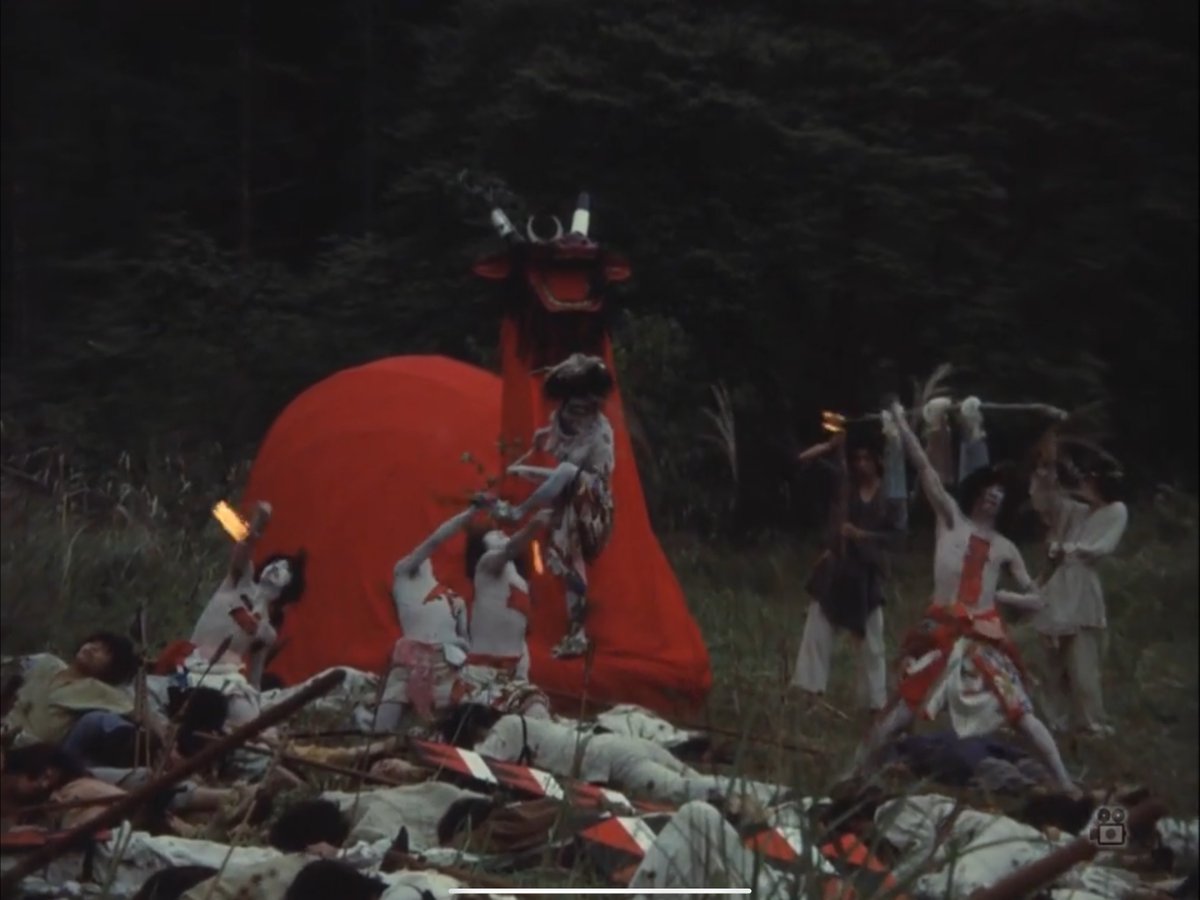

But Tezuka is not alone in combining the story of Himiko and Amaterasu to critique the emperor system. The gifted director Shinoda Masahiro similarly combined myths of Amaterasu and Himiko in his stunning and complex film Himiko from 1974. 6/18

In this film, the rise of the Yamato clan who worship the sun goddess was achieved largely through imperialistic violence and sexual desire, which destroyed the people who worshipped other deities of the land and the mountains. 7/18

The film also extensively employs archaeological imagery and concludes with a helicopter shot of kofun. Shinoda shows that parts of Japan’s past have been buried by conquest and need to be uncovered. For him, archaeology is both a metaphor and an actual necessity. 8/18

Himiko seems to haunt the author to the present day. He published a detailed book-length history (albeit not an academic work) about Himiko in 2019. 9/18 https://www.genki-shobou.co.jp/books/ 卑弥呼、衆を惑わす">https://www.genki-shobou.co.jp/books/&qu...

Here& #39;s how he concludes, "Now, this is what I think: a collective unconscious running from the third-century state that established the Shaman Queen Himiko was operative in Japanese citizenry that supported the 20th-century [idea of the emperor as a] living god…" 10/18

"In Himiko’s sorcery, we can see the origin of the emperor system, which worships the female god Amaterasu…Japan is a rare country in the world in which primitive myths underly contemporary society.” 11/18

While these artists in the decades immediately following WWII retold myths to critique the emperor system, more recent work has considered gendered hierarchies and retold myths to challenge the patriarchy. 12/18

Kirino Natsuo, the famed novelist, has combined Okinawan myth from Kudakajima with the Kojiki’s story of Izanami in her Goddess Chronicles translated by Rebecca Copeland ( @StlRebecca). 13/18 https://groveatlantic.com/book/the-goddess-chronicle/">https://groveatlantic.com/book/the-...

The very structure of her world is unjust and tragic—the island setting is shaped like a teardrop. But the rules that enforce the gendered hierarchies prove arbitrary and manipulated by men for their own purposes. This is true for Izanaki and his parallel Mahito. 14/18

As Copeland writes, Kirino’s novel shows that “Purity/impurity, through represented as divinely determined, are nothing more than a human mechanism for social control.” 15/18 https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520297739/diva-nation">https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780...

Altogether, these post-war works to some extent oppose myth-making projects. If myth is “ideology in narrative form” and functions to naturalize power structures, these authors and artists pull back the curtain to expose myths as human projects and not an inherent order. 16/18

In some ways, they go further by using the original myths themselves to subvert the dominant order. Perhaps only myth can dismantle myth. 17/18

I hope my students learn, at the very least, the power of narrative to both maintain an order and subvert it. These are lessons that are obviously relevant today. 18/18

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter