New paper reviewing evidence on the impacts of cross-sector partnerships on health and health inequalities. The findings are relevant to policy initiatives in the UK, US, and elsewhere. (They are also not particularly surprising.)

A quick summary below https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-10630-1">https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/...

A quick summary below https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-10630-1">https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/...

Collaboration between health care, social services, and other agencies is widely seen as a route to improving population health. This makes sense—the logic behind collaboration is typically good—and partnership working is nothing new

England, for instance, has a long history of partnership policies—like health action zones, local strategic partnerships, integrated care pioneers, sustainability and transformation partnerships, integrated care systems, lots more

Despite this, we don’t know much about the impact of cross-sector partnerships between local agencies on health outcomes. Evidence that partnerships achieve their objectives—eg better health or reductions in inequalities—is hard to find

We reviewed existing reviews of the evidence on health-related impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organisations, as well as factors affecting how these kinds of partnerships functioned

This included evidence on varying forms of collaboration in diverse contexts. Some reviews focused on collaborations with broad goals, eg preventing disease, reducing inequalities. Others were narrower, eg better health and social care integration. Various things were excluded

Overall, we found little convincing evidence to suggest that collaboration improves health outcomes. Evidence of impact on health services is mixed. And evidence of impact on resource use and spending are limited and mixed

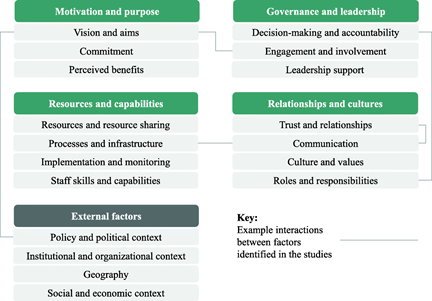

Despite this, lots of studies reported on factors thought to be associated with better or worse collaboration. Here’s a simplistic summary of these factors:

Several factors, such as quality of communication between partners and availability of resources, appear consistently across multiple studies. But data linking factors in these domains to collaboration outcomes is sparse

This doesn’t mean that collaboration is bad or ill-advised. There may be several explanations for the lack of evidence on impact. They include:

Explanation 1—the emperor may simply have no clothes: collaboration between health care and non-health care organizations may not deliver the kinds of impacts that many policymakers expect

Explanation 2—collaborations may be fiendishly difficult to do, so while effective partnerships may contribute to better health, implementation issues render them rare

Explanation 3—the effects of collaborations are difficult to measure, given they are hard to define, involve multiple orgs and interventions spread over space and time, have diverse and often long-term aims, and operate alongside many other factors that affect health

A mix of these (and other) explanations may be true—with benefits overestimated, hard to deliver, and hard to measure

Ultimately, local collaborations are shaped by the broader social, political, and economic structures in which they operate. Better communication, say, may help agencies coordinate local health interventions...

But broader policy decisions—eg, government policies on the level and distribution of spending on income support, education, and social services—will fundamentally shape health and health inequalities in those communities

Local collaborations should therefore be understood within their broader political context, and alongside other interventions that interact to shape health. Conceptualizing collaborations as one component in a complex system may help us better understand their potential impact

The paper has plenty of limitations. Collaboration is often broadly defined and weakly described, our search was broad but still likely limited, and our umbrella review approach meant a wide mix of interventions were studied together. The evidence we reviewed was mostly weak

But the review hopefully has some useful pointers for policy and practice—particularly given partnership working is in vogue. Will follow up with a shorter paper focused on the UK evidence and some broader policy analysis soon

May be of interest to @davidjbuck @felly500 @SIREN_UCSF @harryrutter @RuthRobbo @Strategy_Unit @amy_galea @chrisbnaylor @nedwards_1 @DrJudithSmith (and thanks @ADMBriggs, plus other non-Twitter coauthors)

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter