1/ Hello again, everyone. I have finally put together my third Tweetorial, and I will be focusing it on one single entity, the enigmatic and often frustrating Low-Grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm (LAMN). #pathology #GIpath

2/ For starters, what is a LAMN? The name gets you most of the way there. It technically is an appendiceal adenocarcinoma, because it is an epithelial malignancy composed of glandular epithelium.

3/ The key distinction is that LAMN invades by pushing rather than trickling/destructive invasion, so it’s not a low-grade “adenocarcinoma” like those we often see in the colorectum.

4/ In 2016, the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) codified their definition of LAMN, which I like. First, it has to be an epithelial neoplasm. This rules out many mimics in the differential diagnosis (which I’ll discuss later). Ref: https://bit.ly/3eashSk ">https://bit.ly/3eashSk&q...

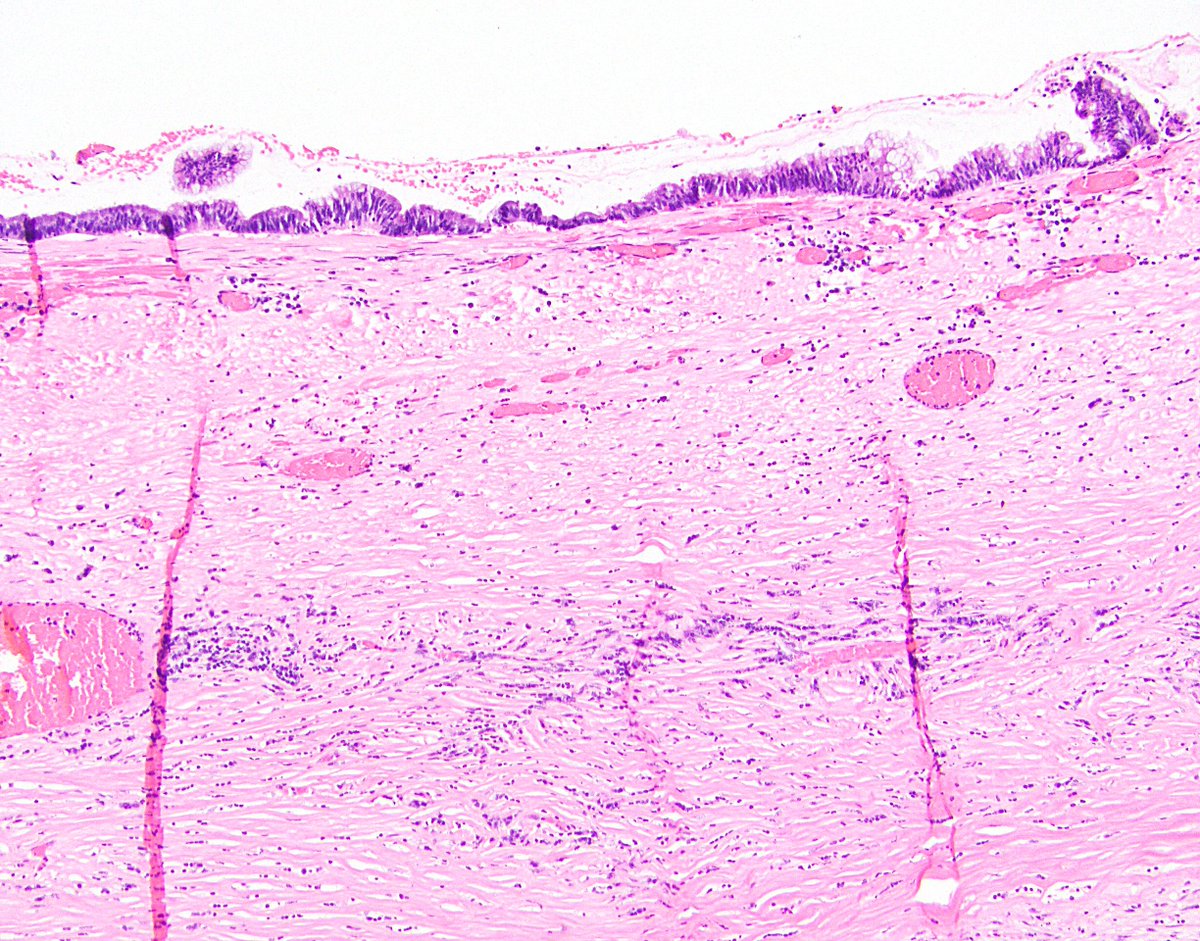

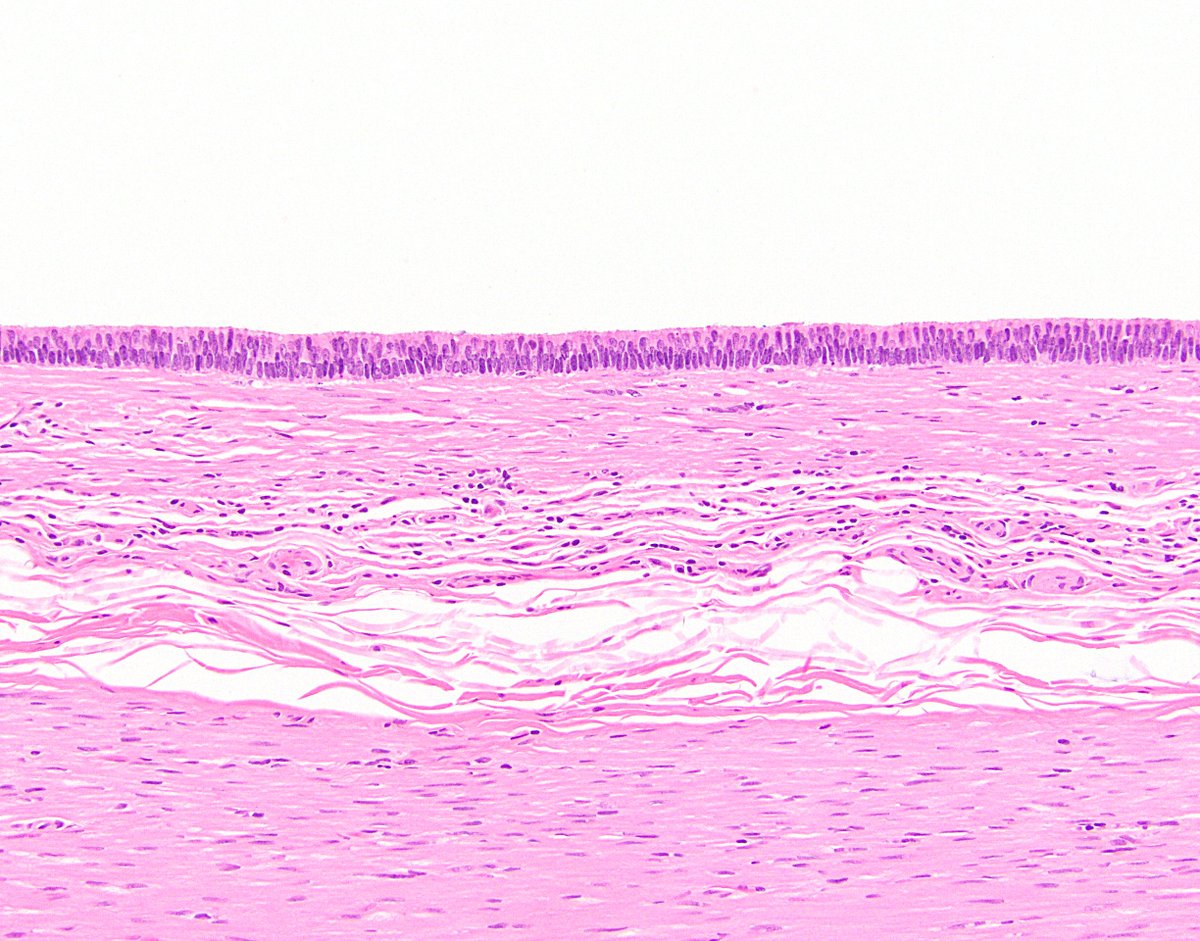

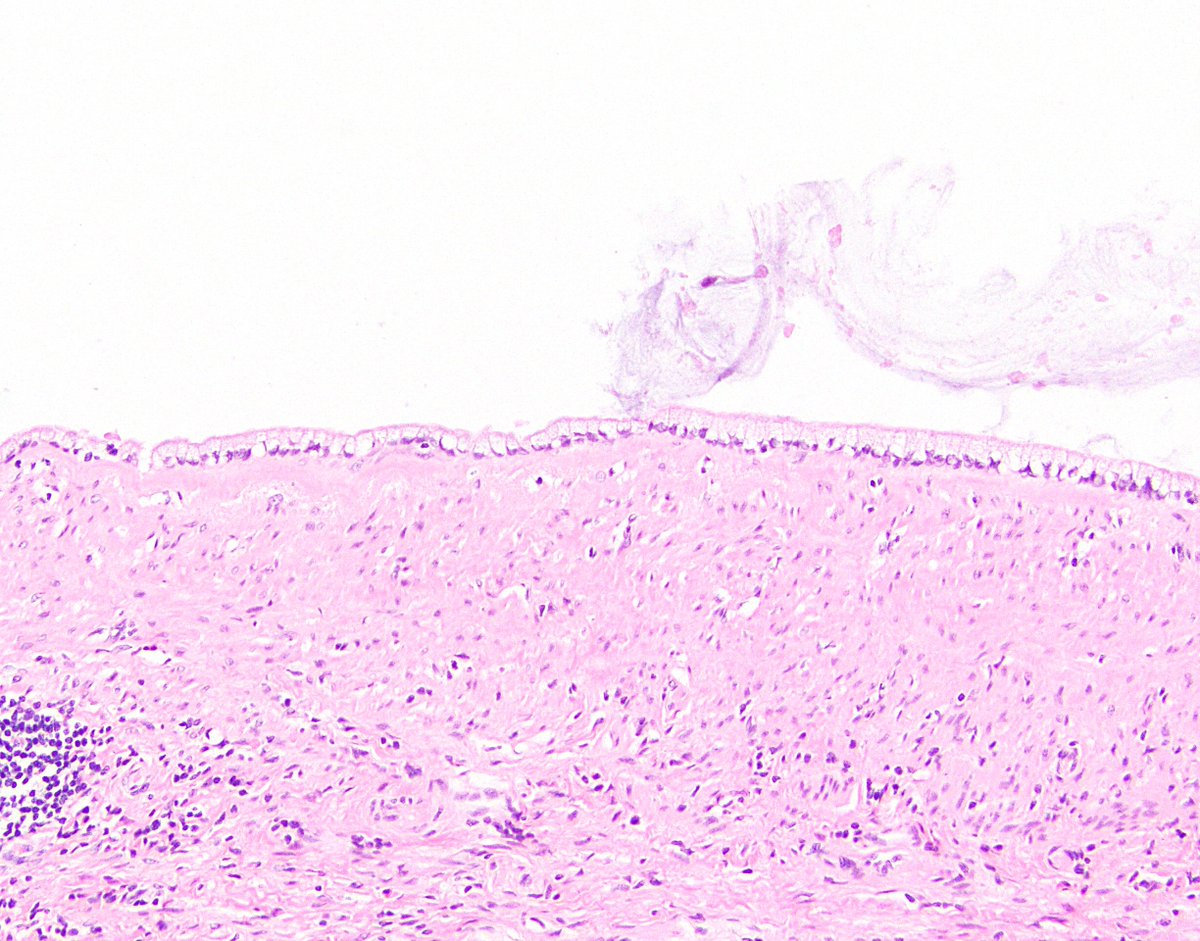

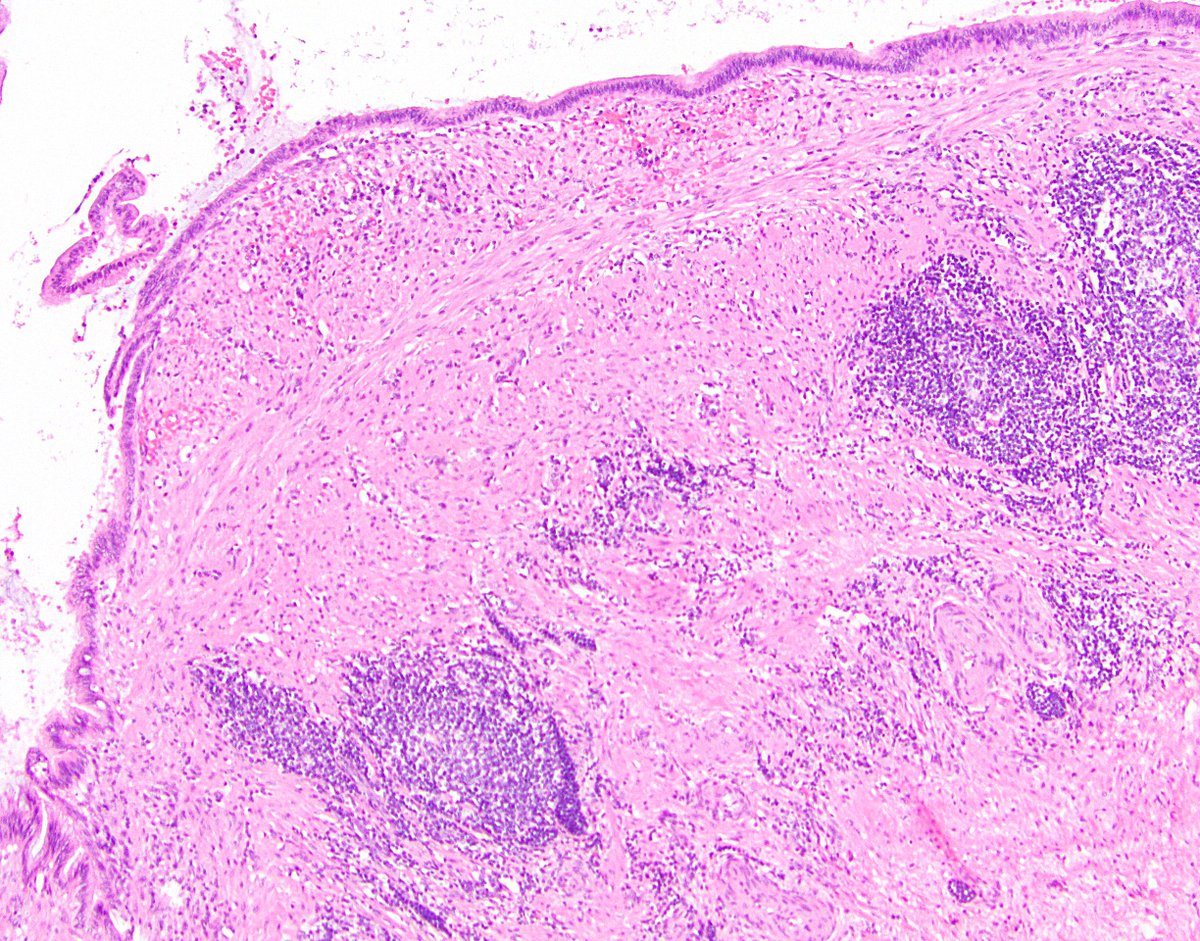

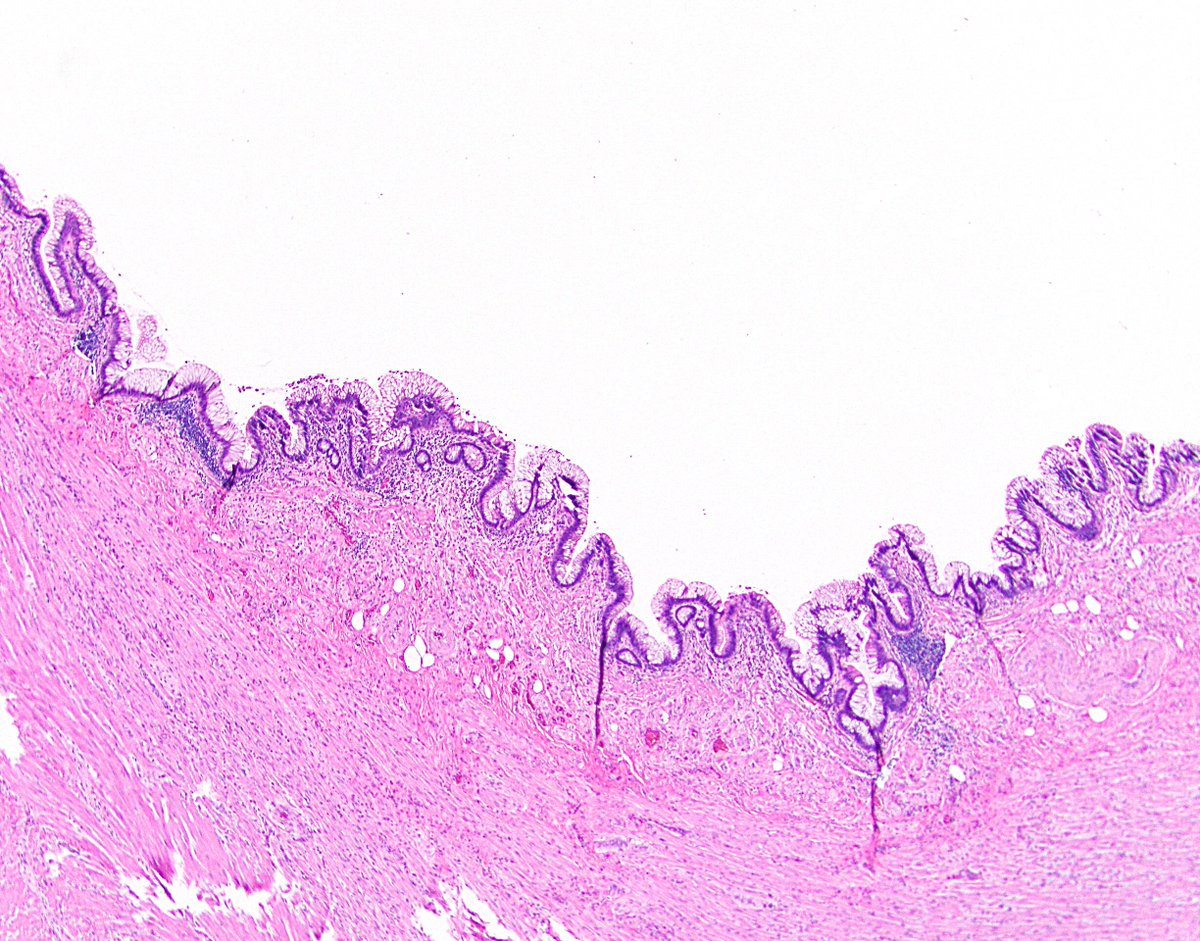

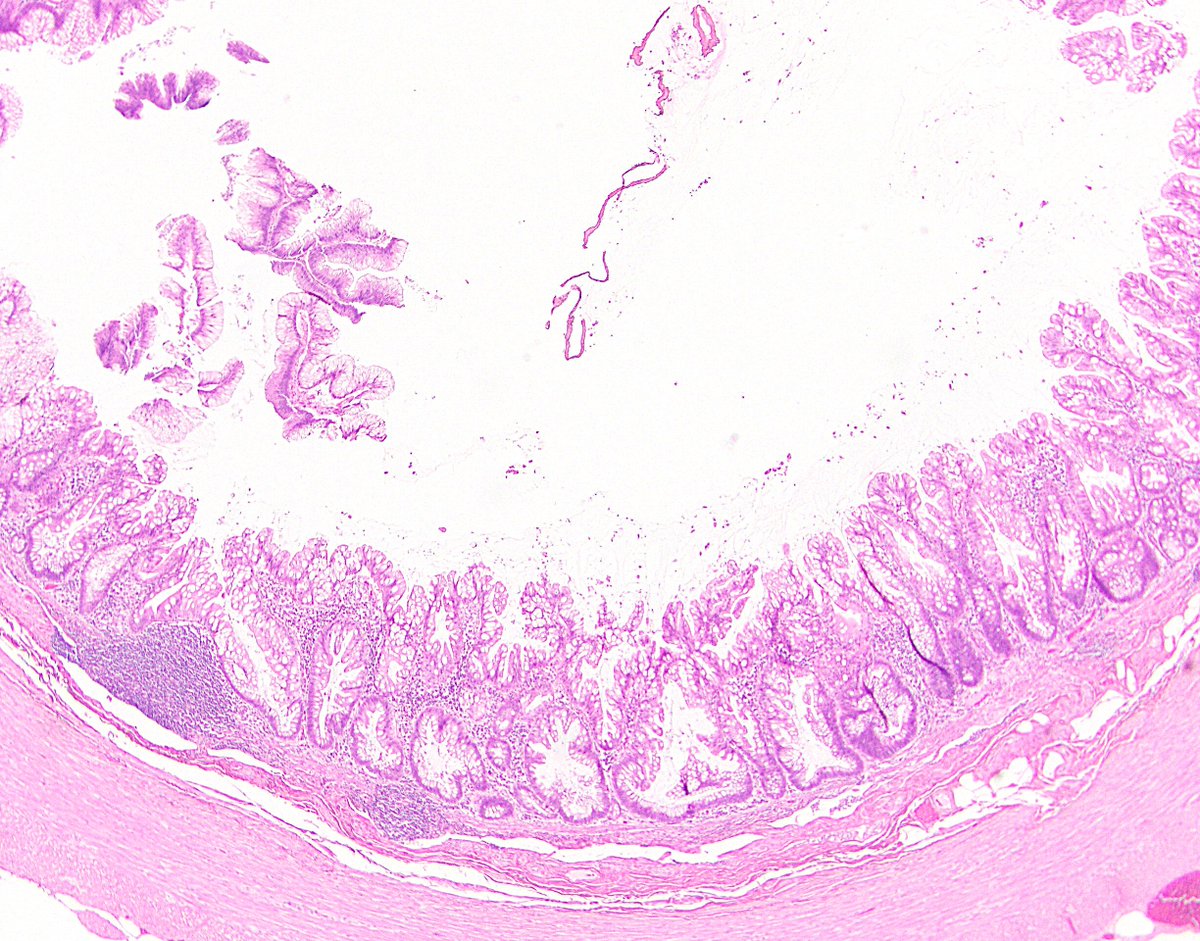

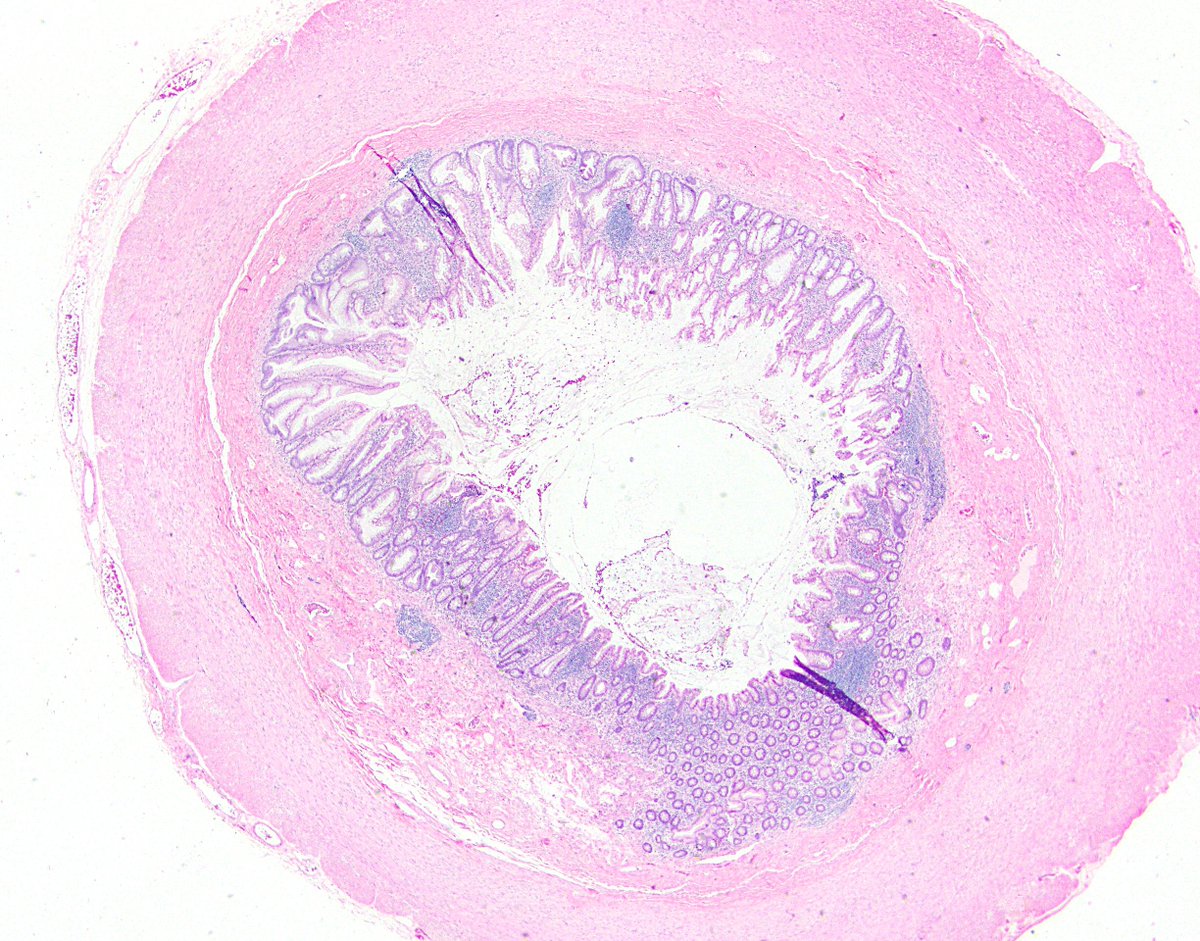

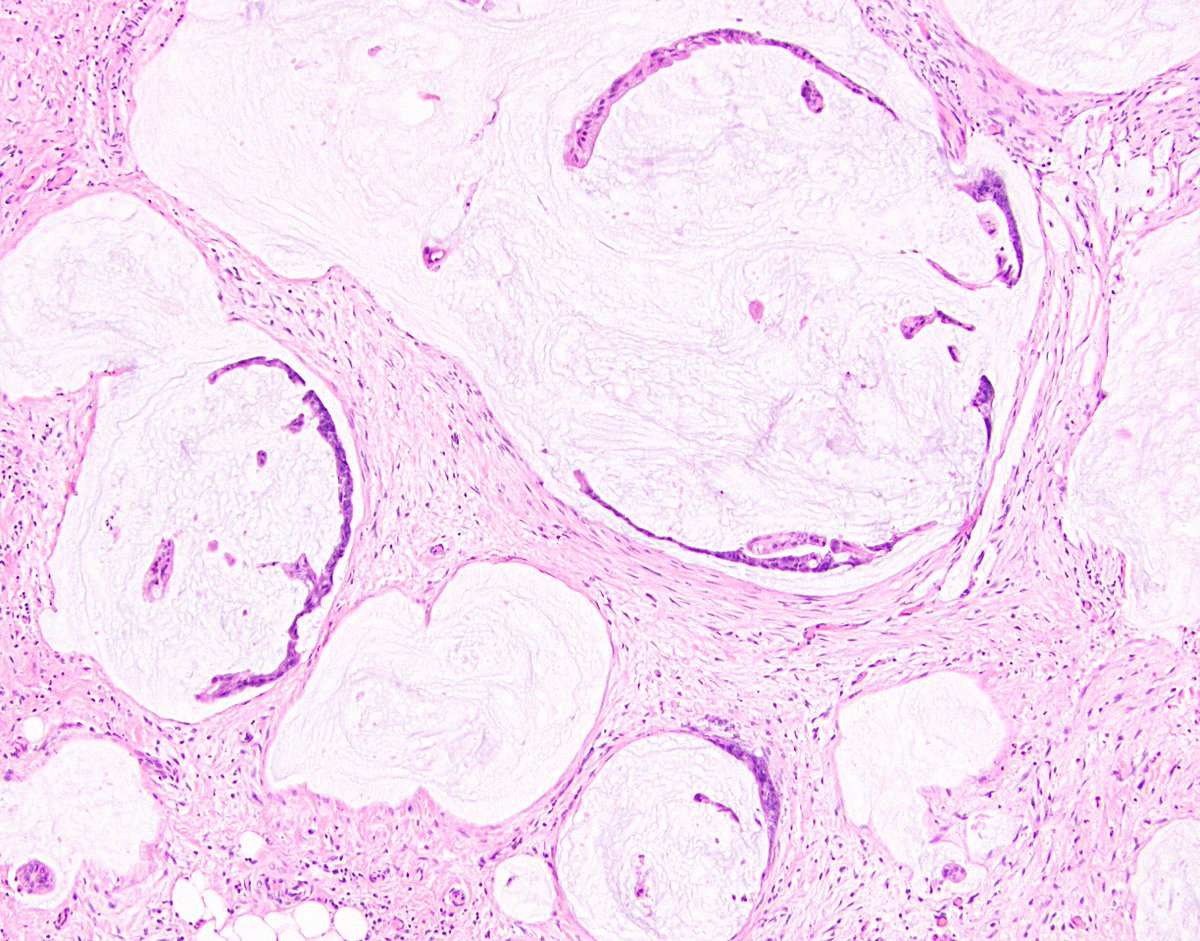

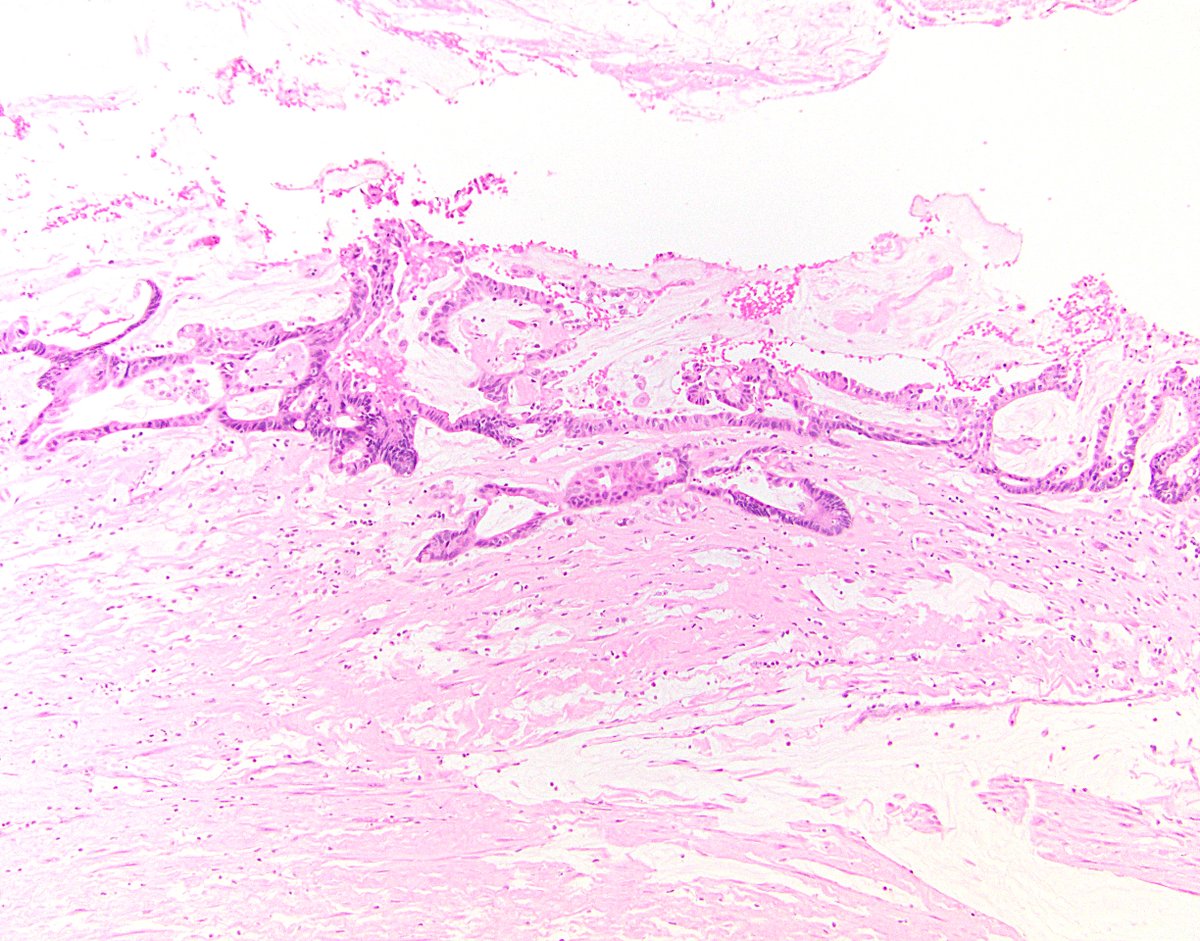

5/ In addition to that mandatory top-level criterion, it has to meet one of 7 additional criteria. 1. Loss of muscularis mucosae. This is seen in almost all LAMNs, though it can be patchy. I sometimes see consults with an SMA immunostain to evaluate this, which is not a bad idea.

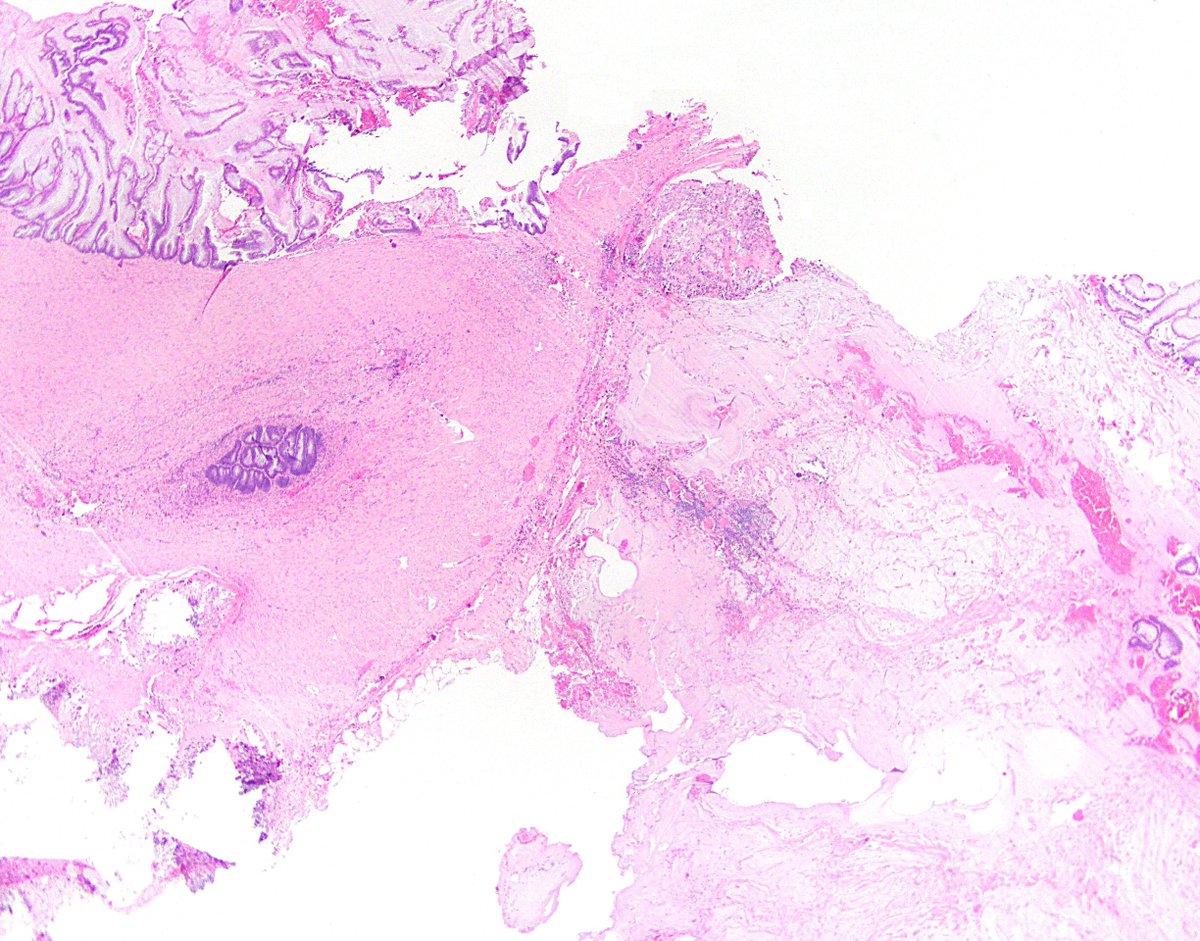

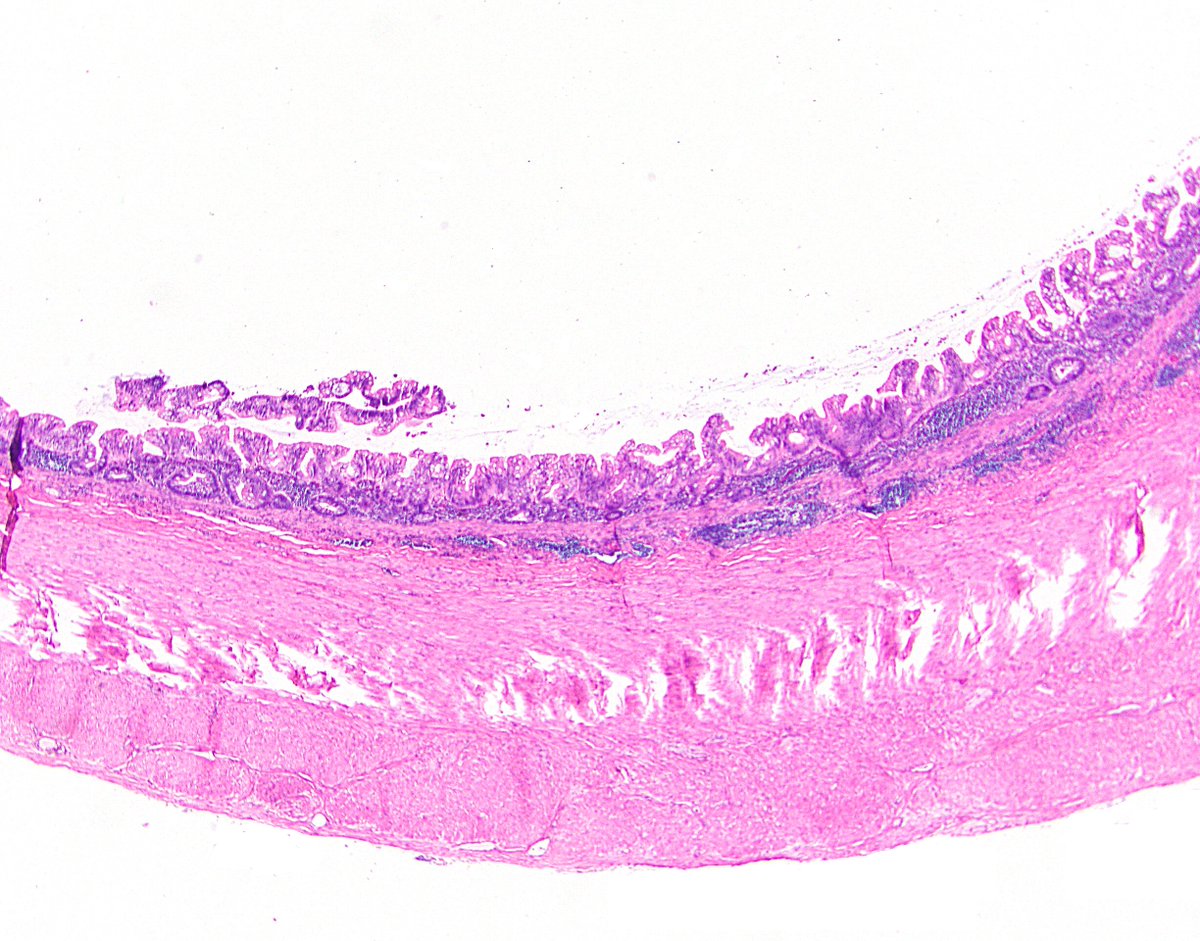

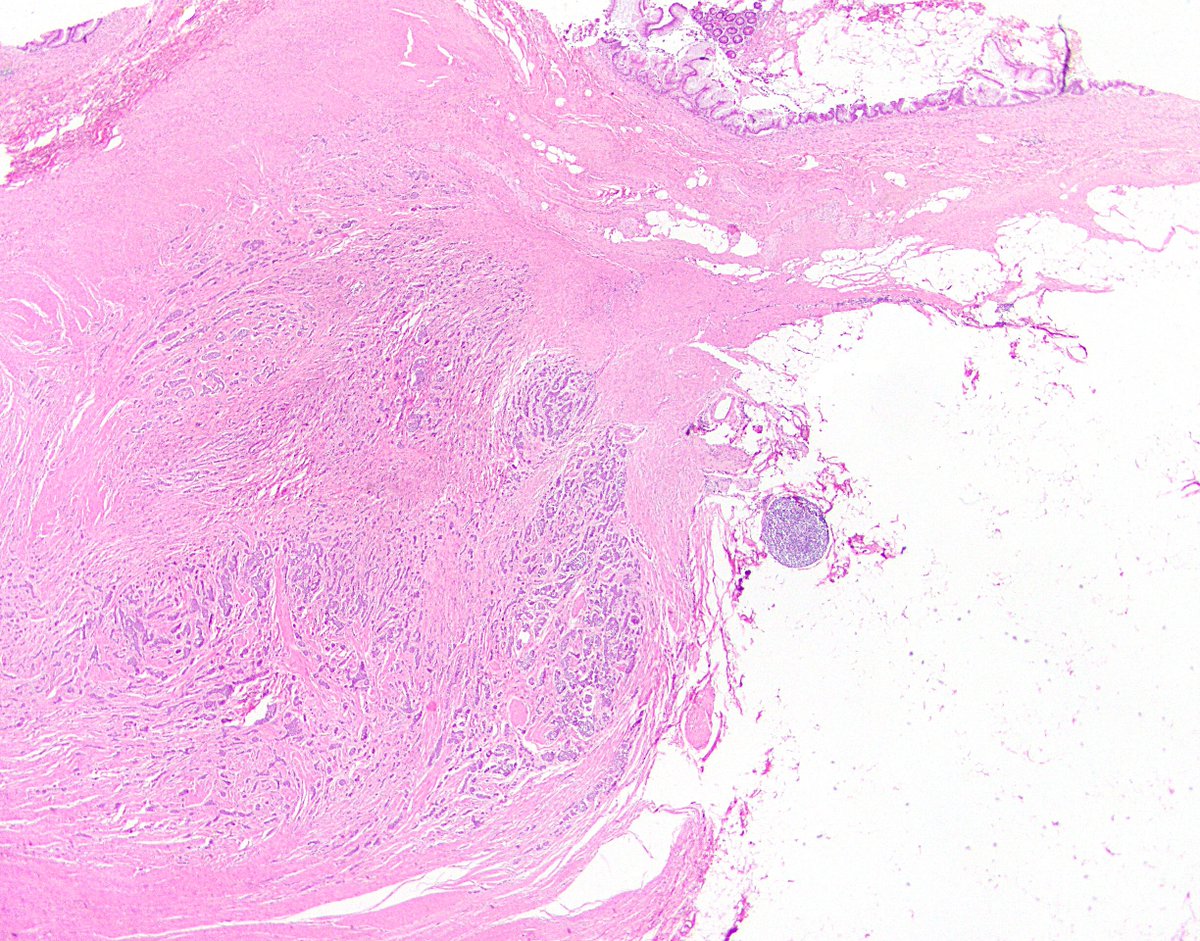

6/ 2. Fibrosis of submucosa. This is fairly common as well, and it can really distort the appendiceal architecture and make it difficult to determine how deep a LAMN goes. This can cause consternation when trying to stage a LAMN (discussed later).

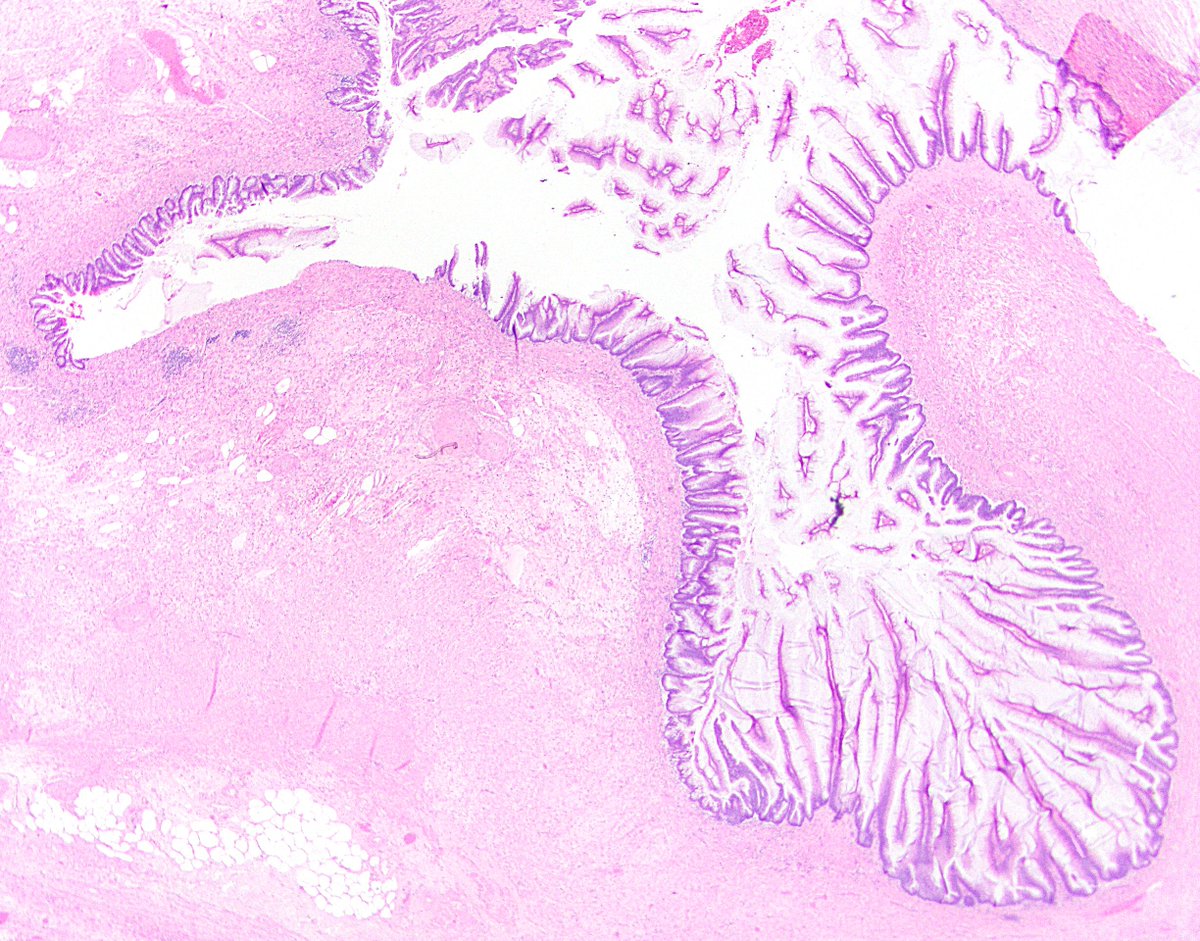

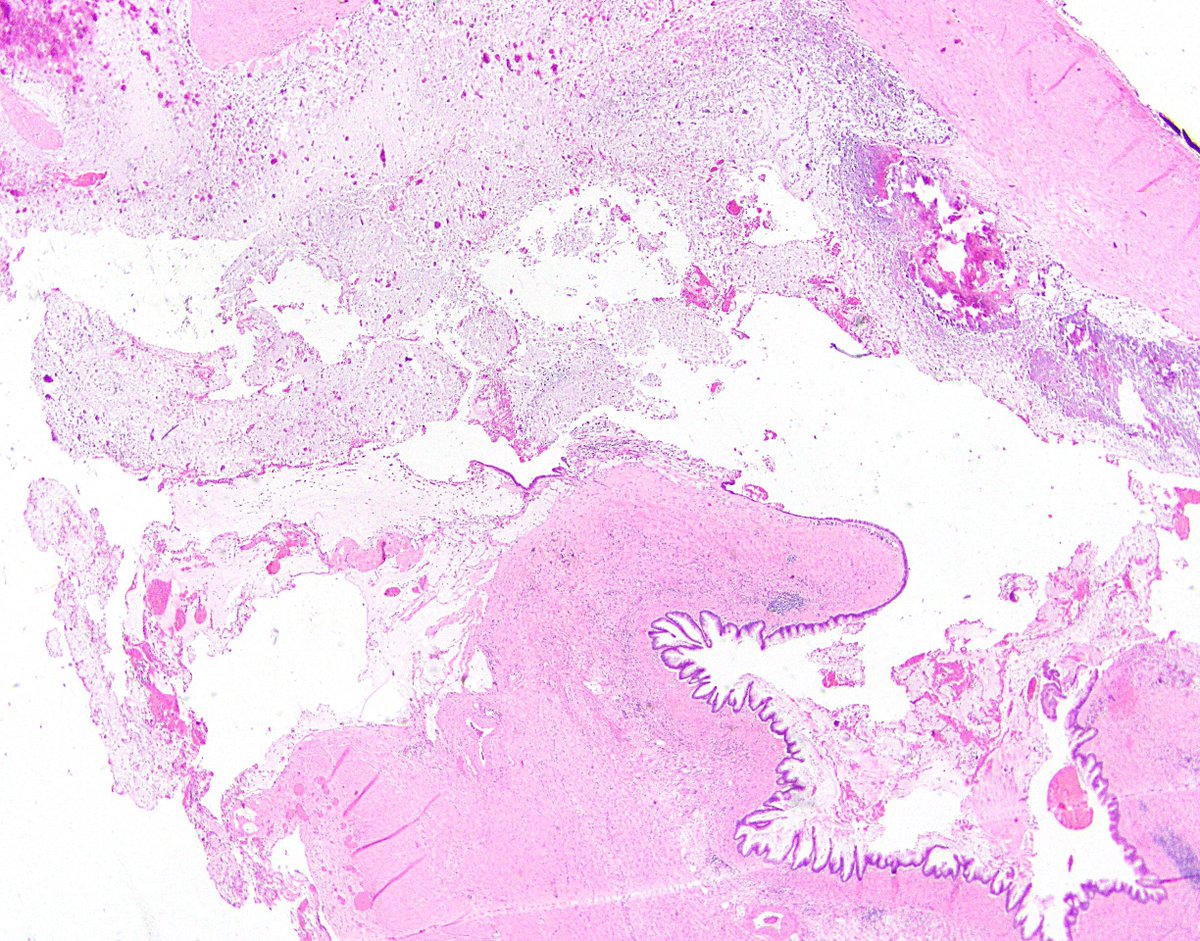

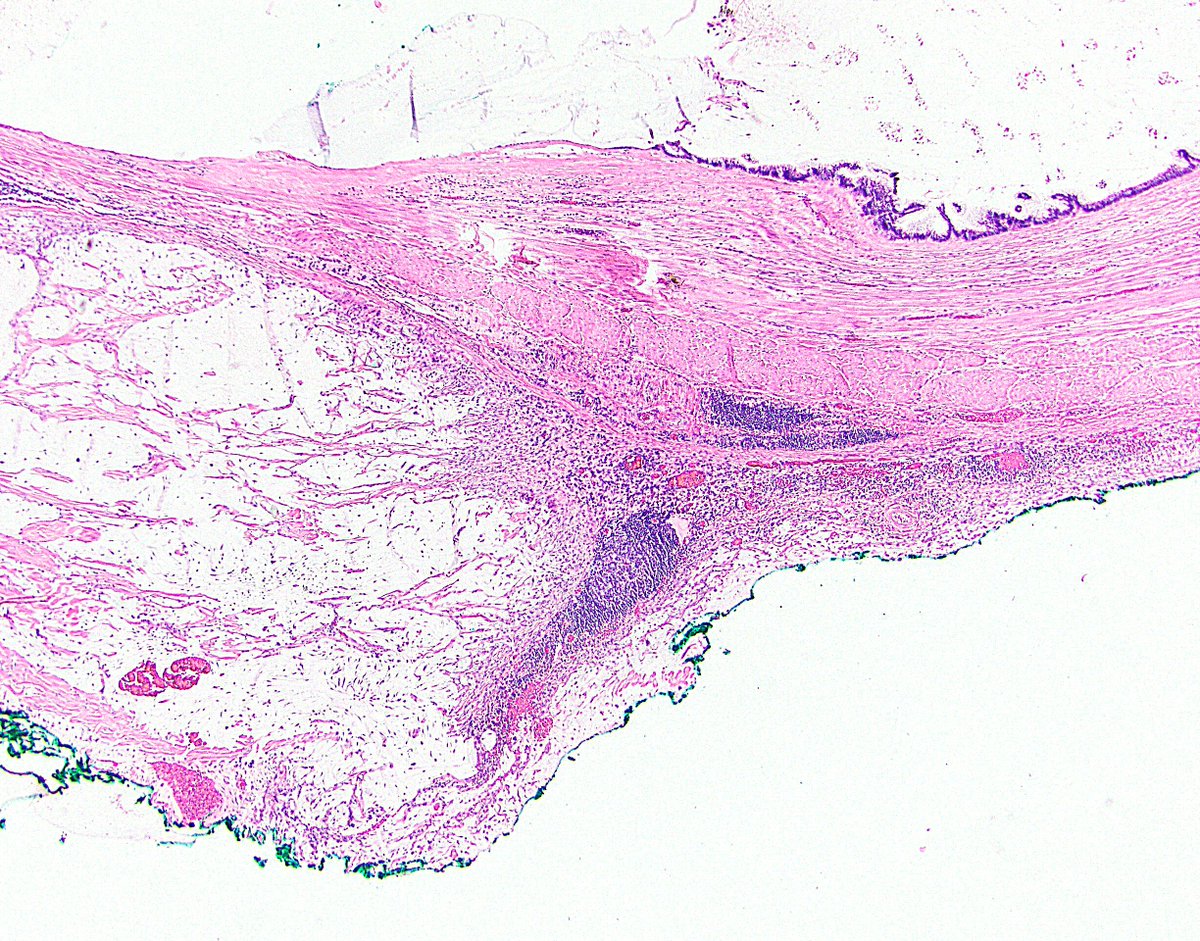

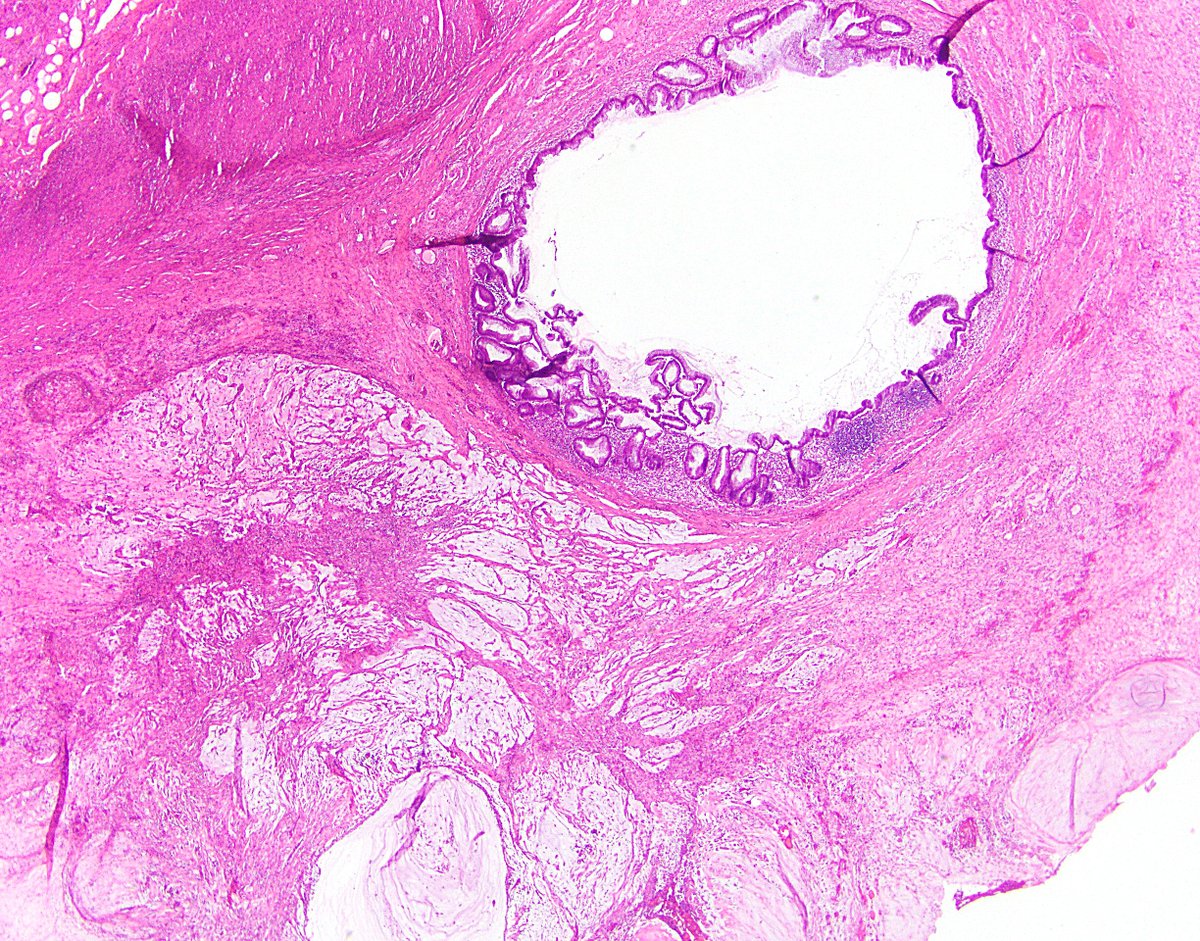

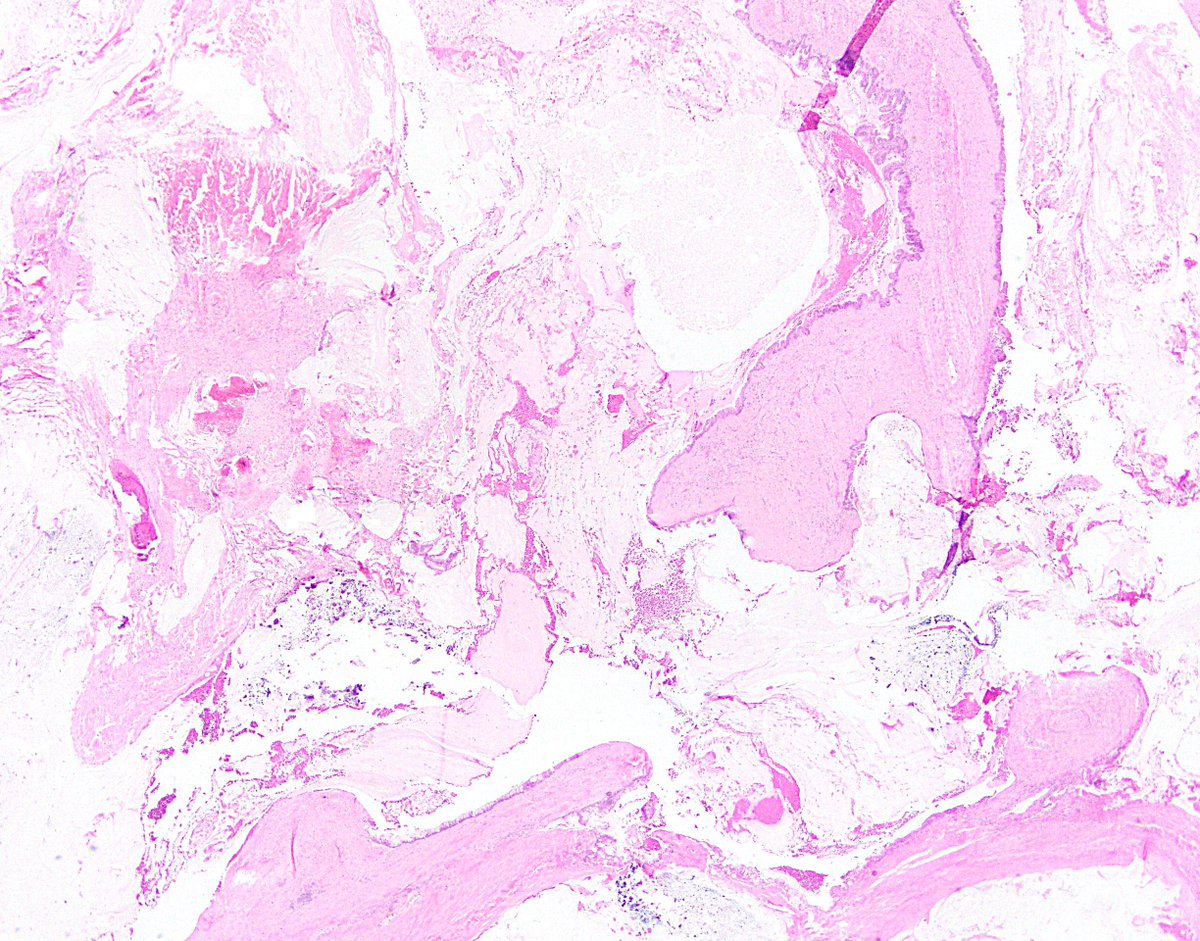

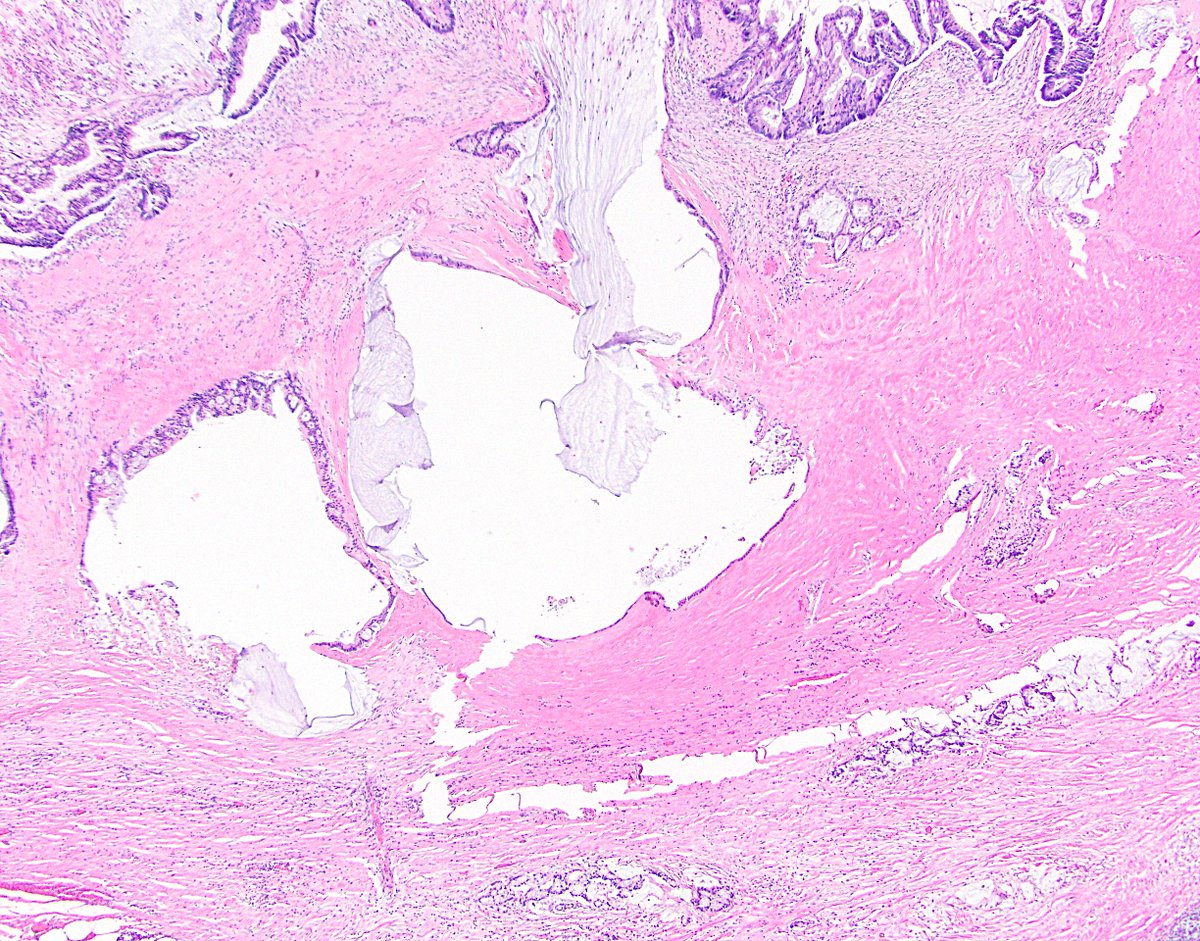

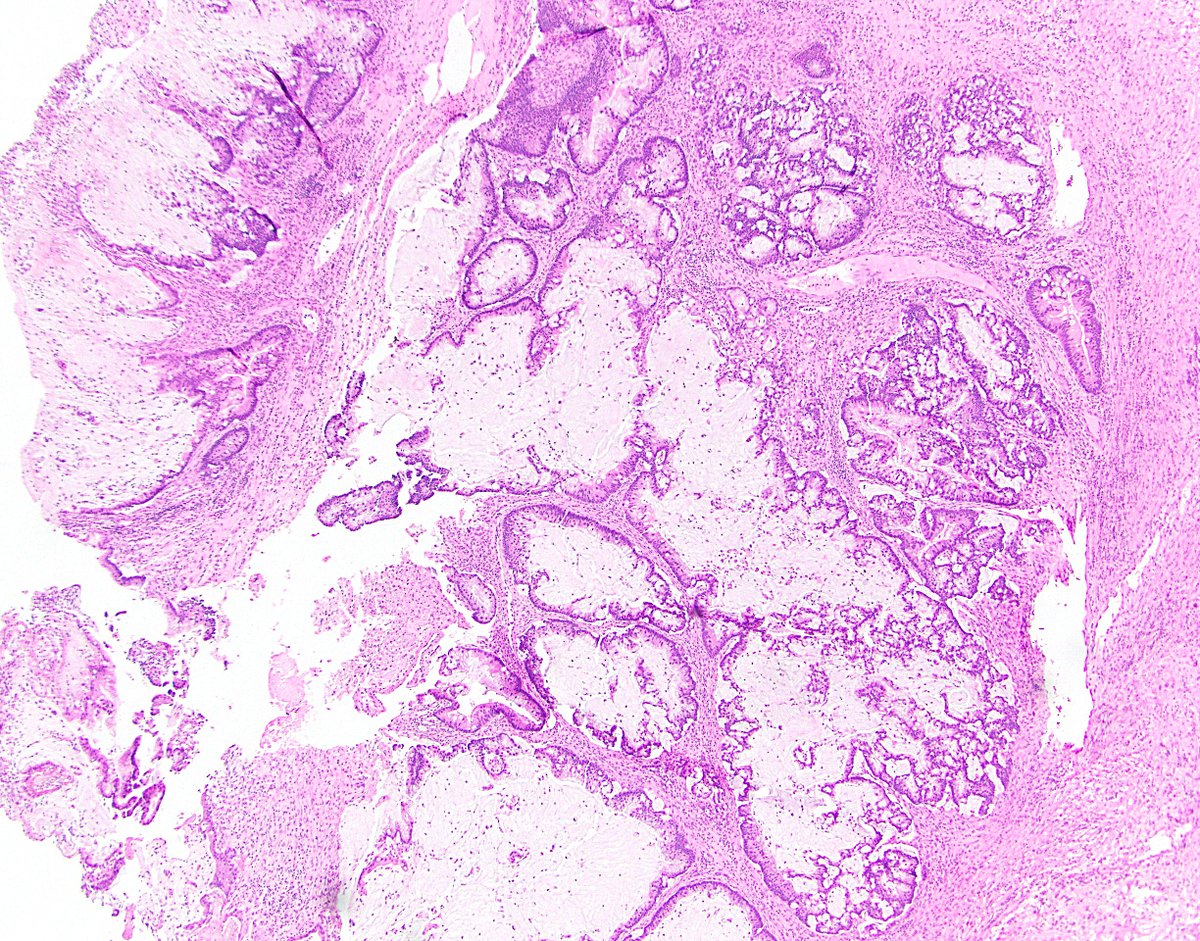

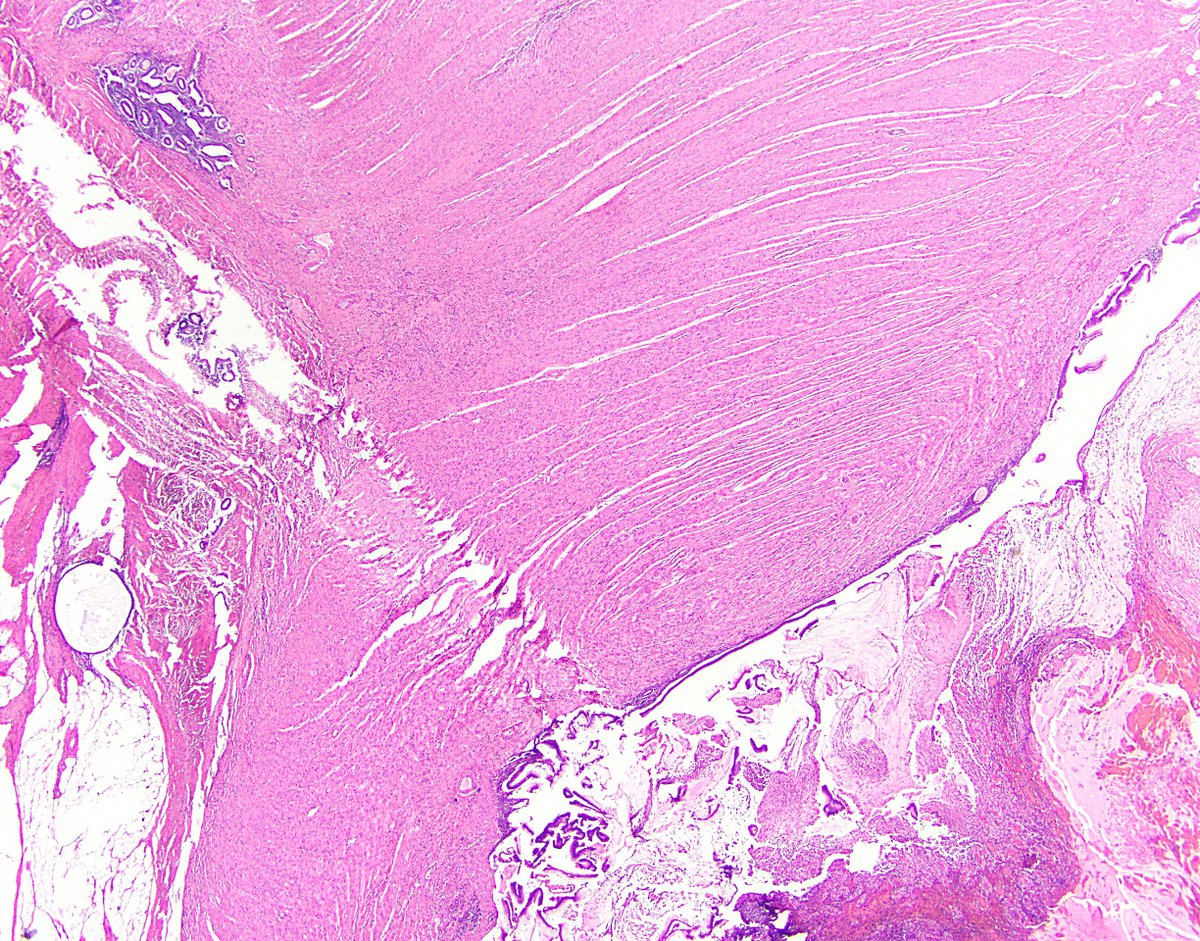

7/ 3. “Pushing invasion” (expansile or diverticulum-like growth). Some LAMNs stay confined to the mucosal space, but other LAMNs progress into the appendiceal wall in this fashion. If they push enough, they can perforate the appendix and gain access to the peritoneum.

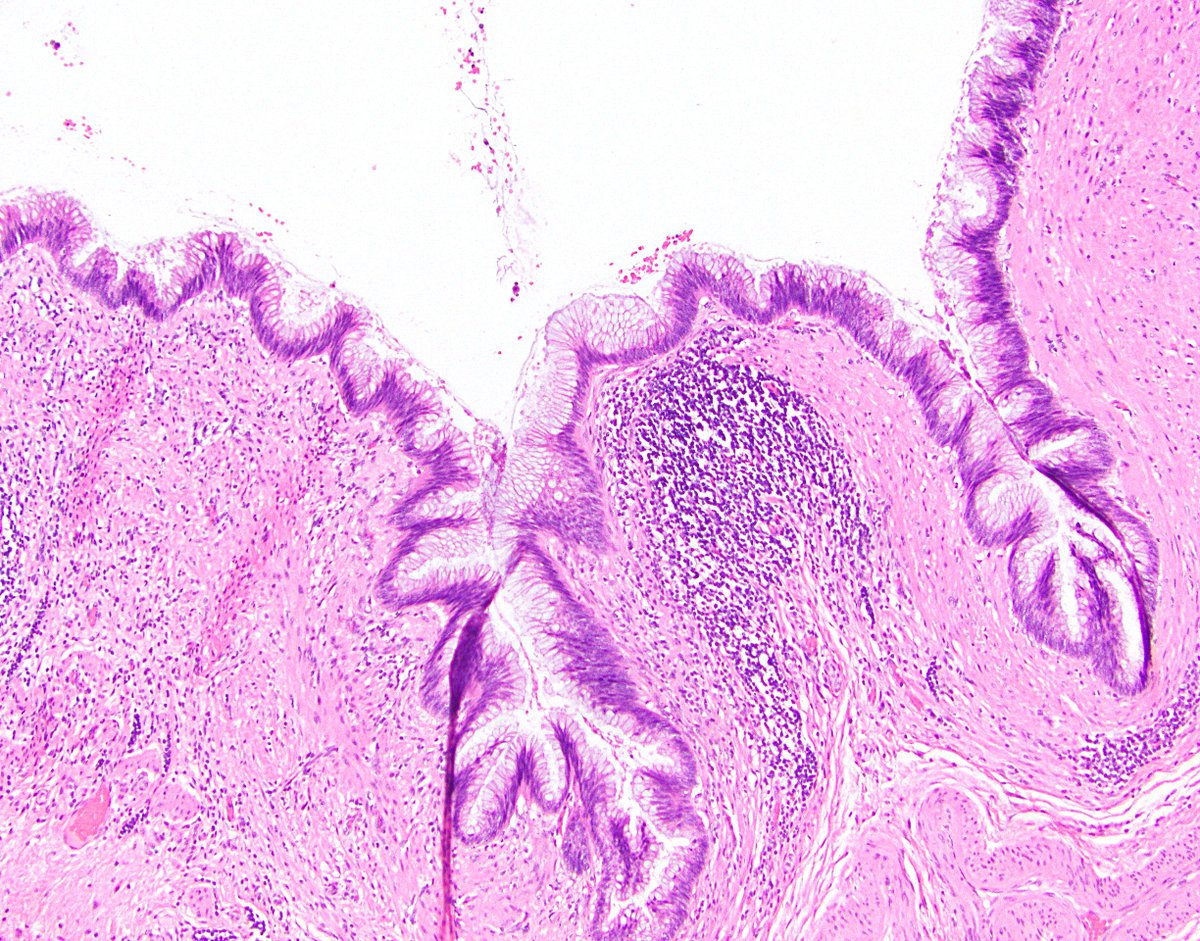

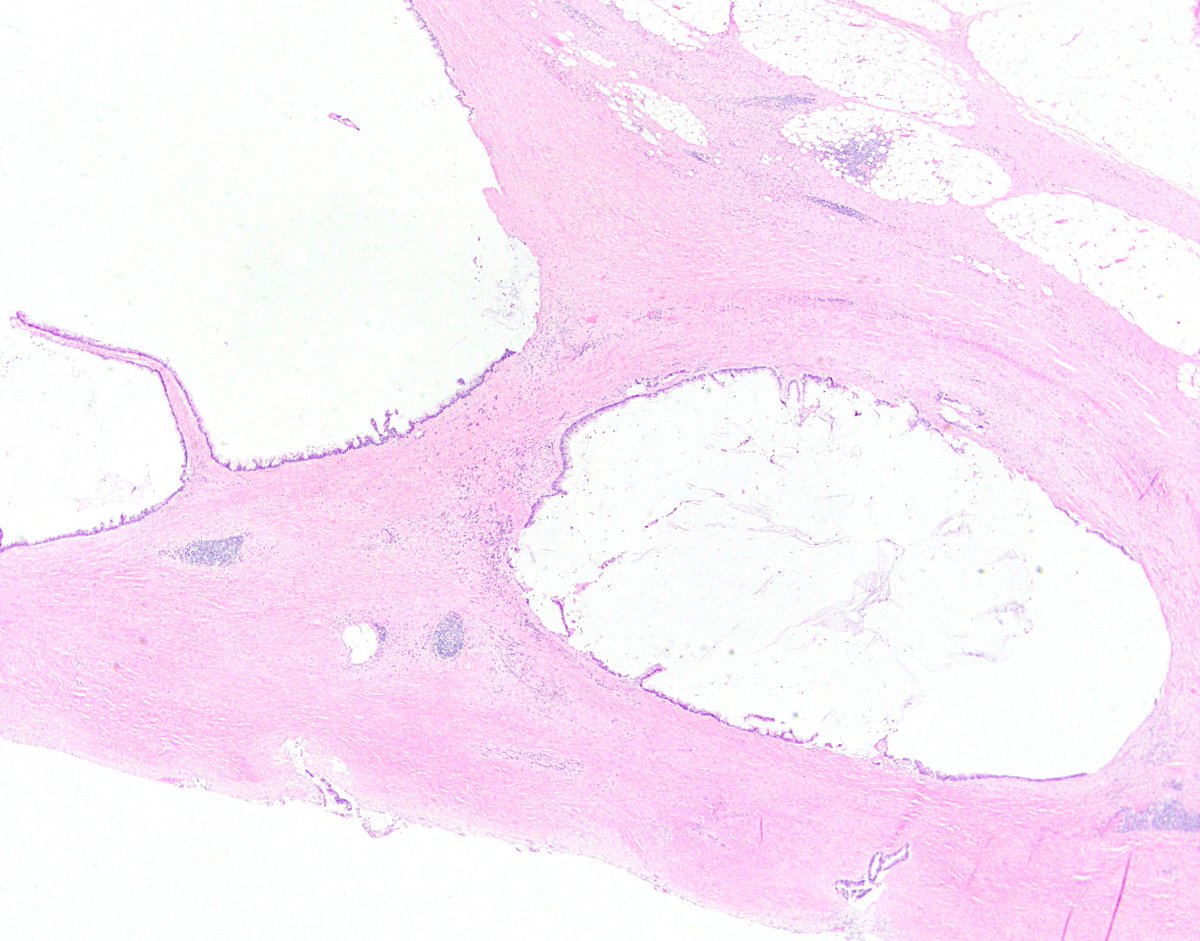

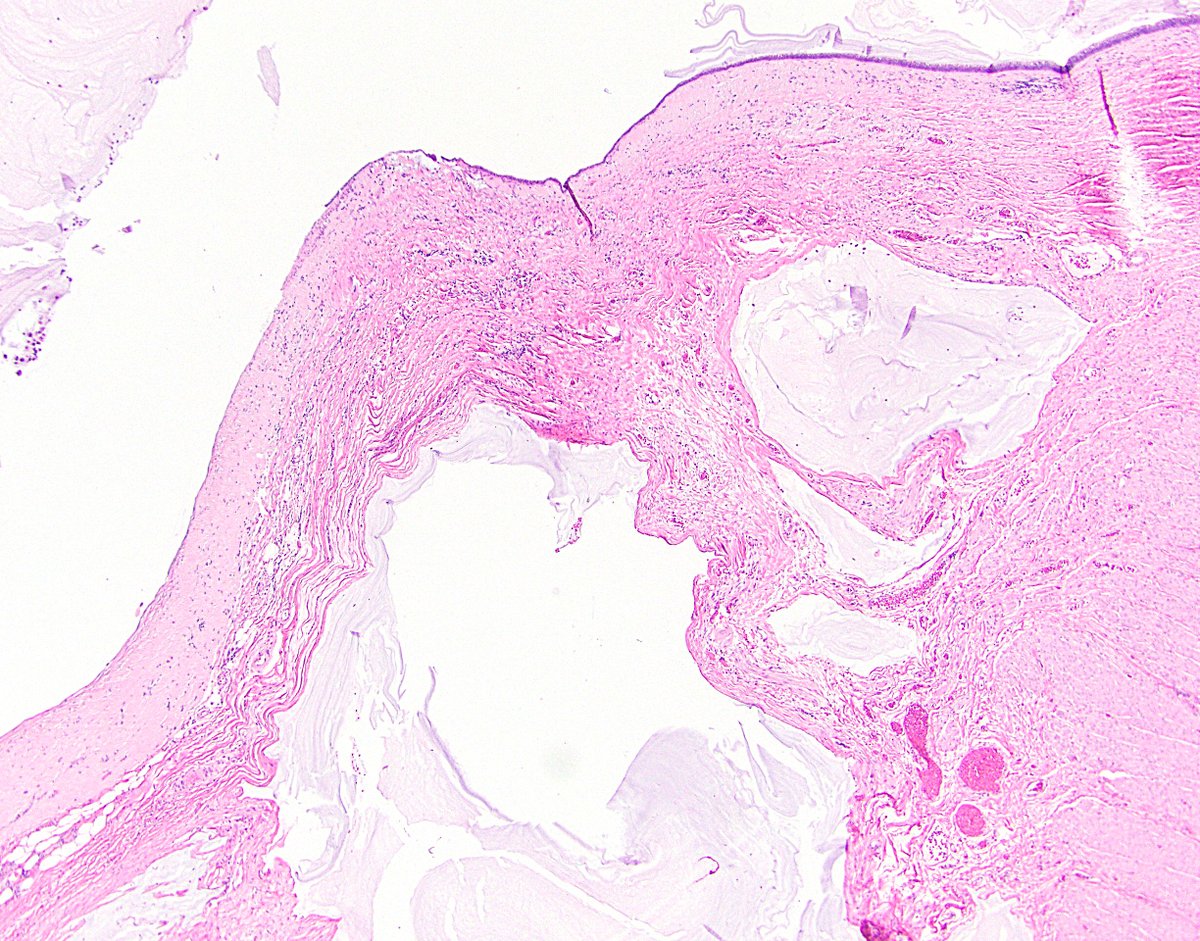

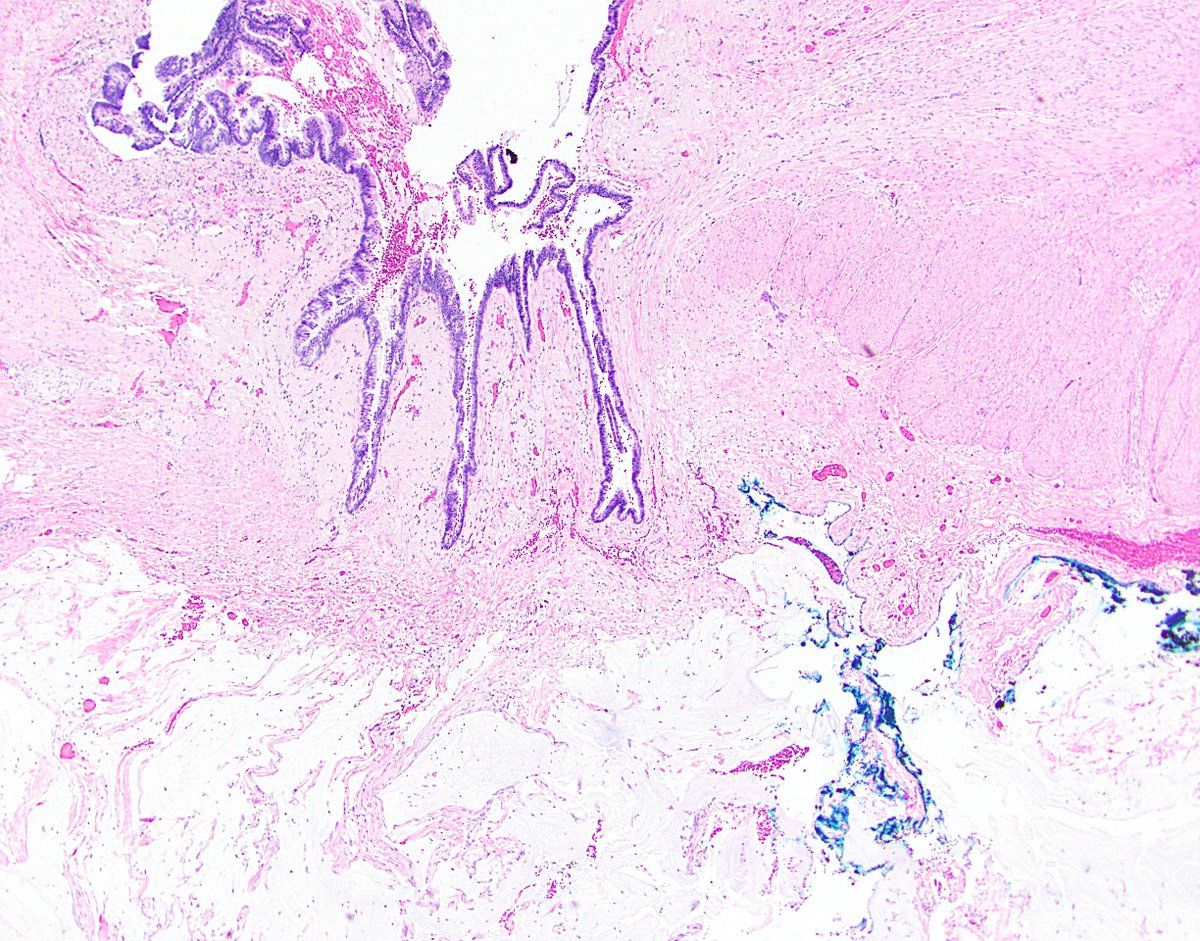

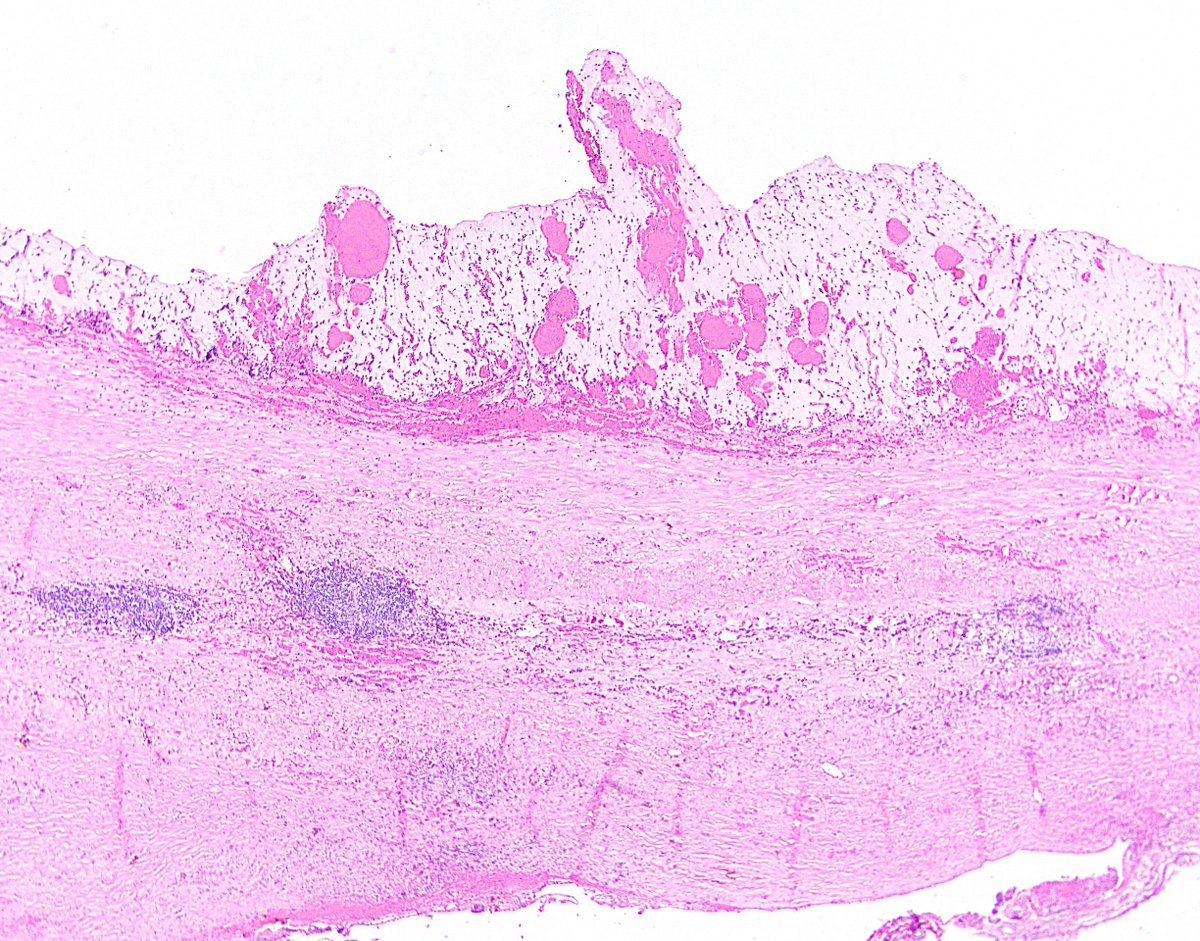

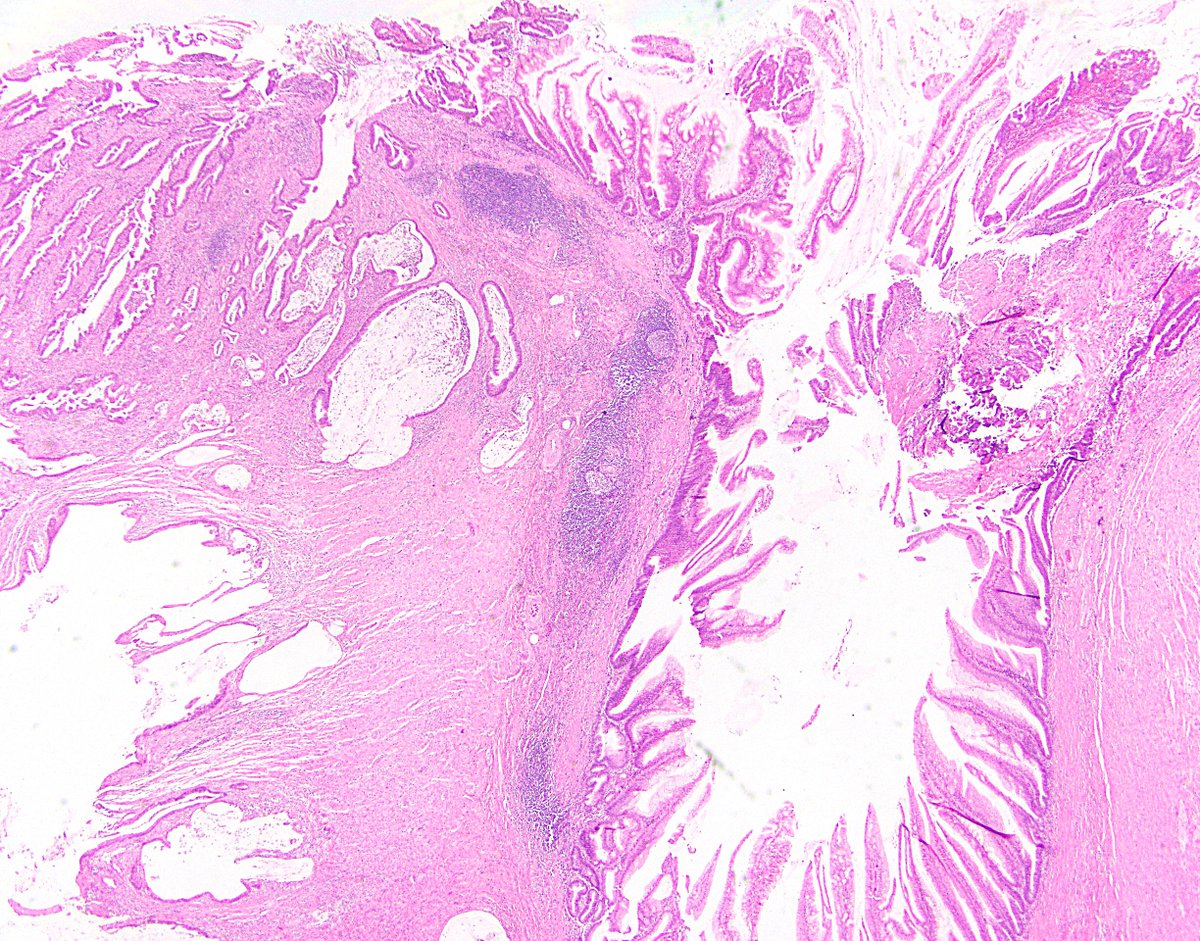

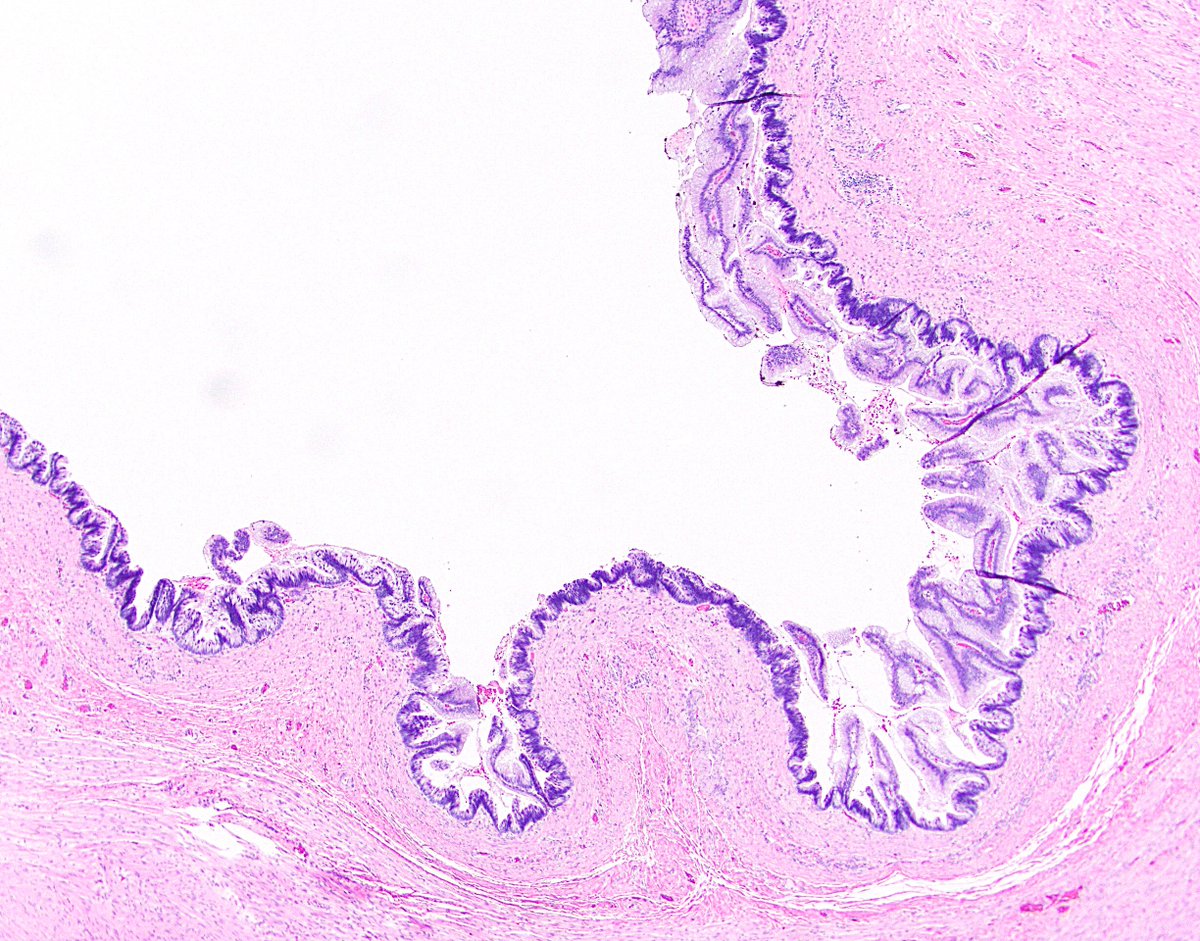

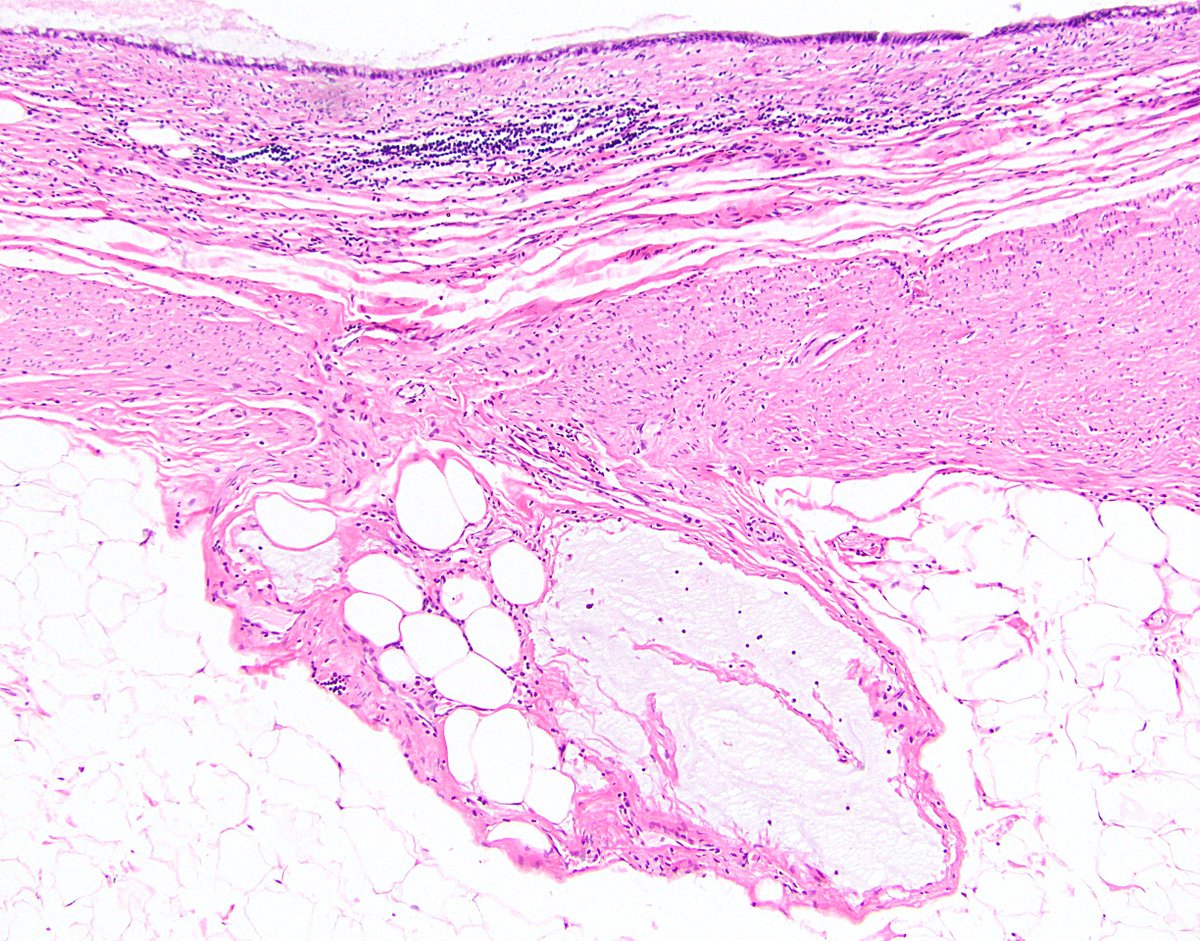

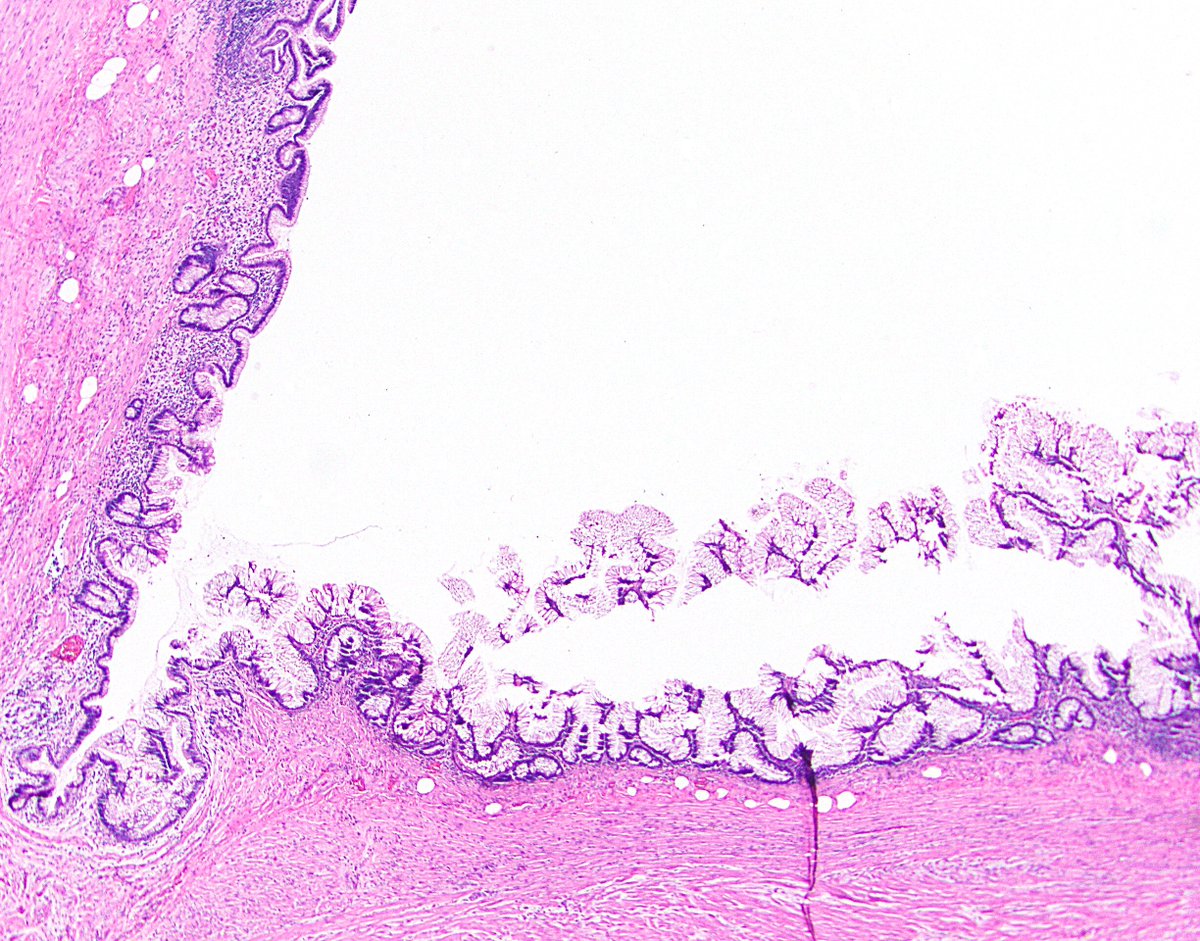

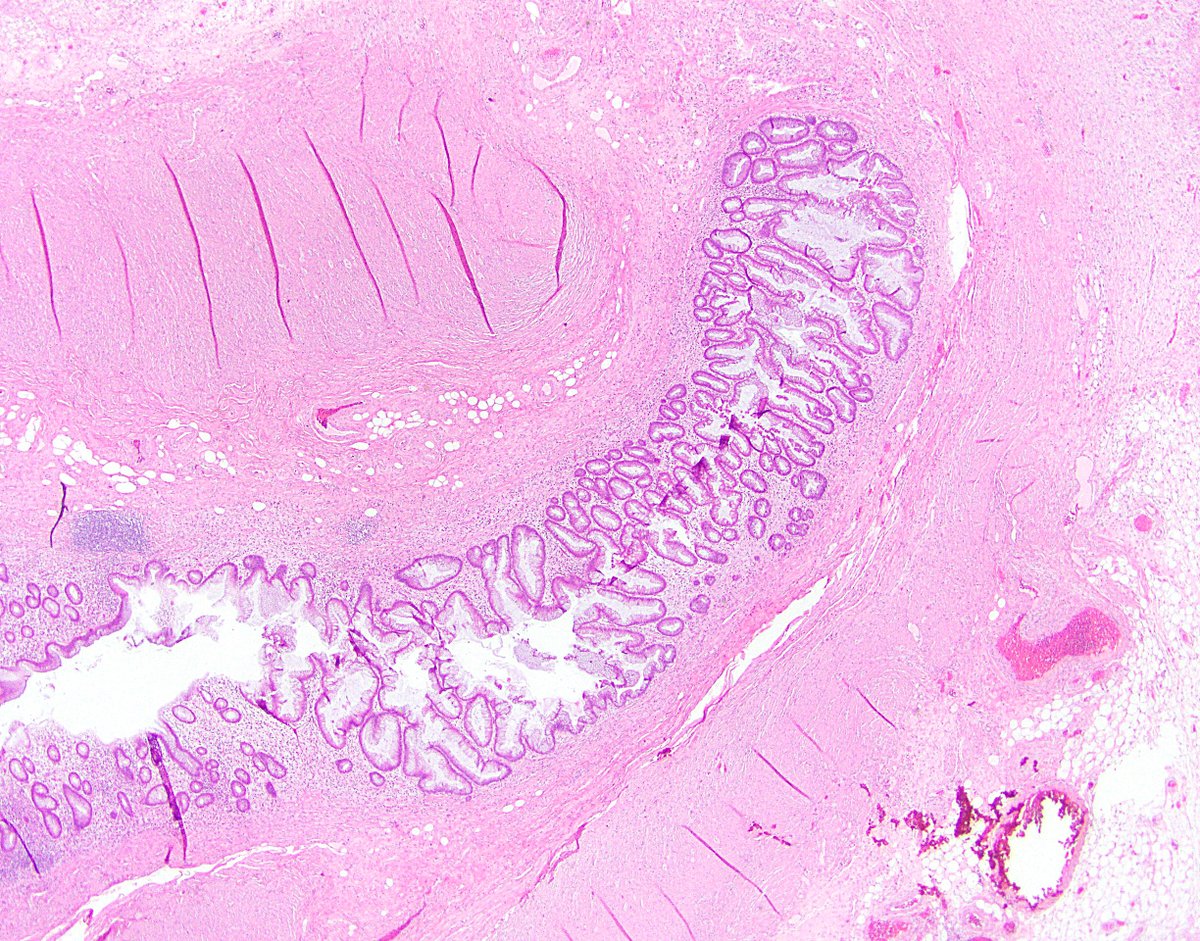

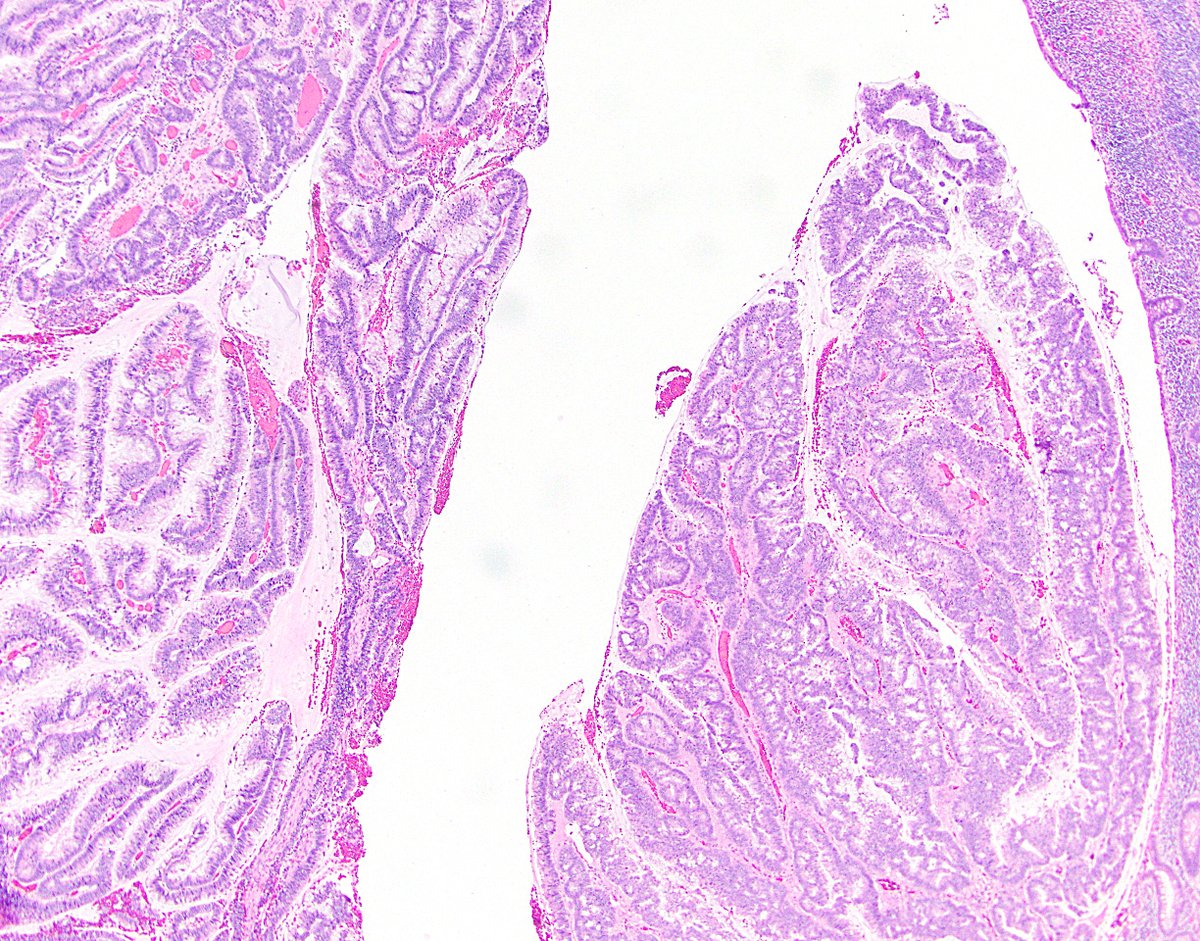

8/ Side note: LAMNs can involve diverticula, which are weak points that make it even easier for the neoplasm to make its way through the wall. The second photo is a nonneoplastic appendiceal diverticulum, just for reference. Ref: https://bit.ly/387mSY7 ">https://bit.ly/387mSY7&q...

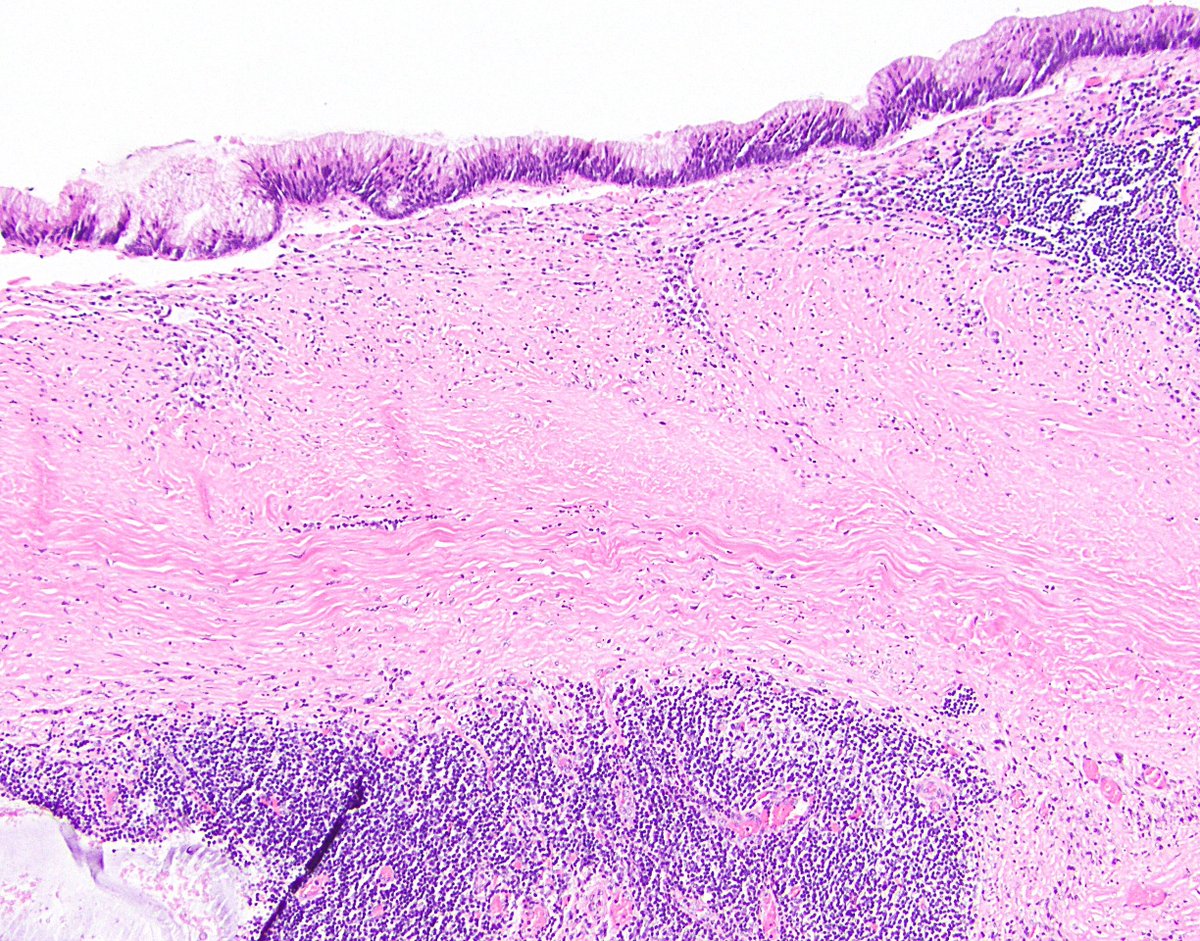

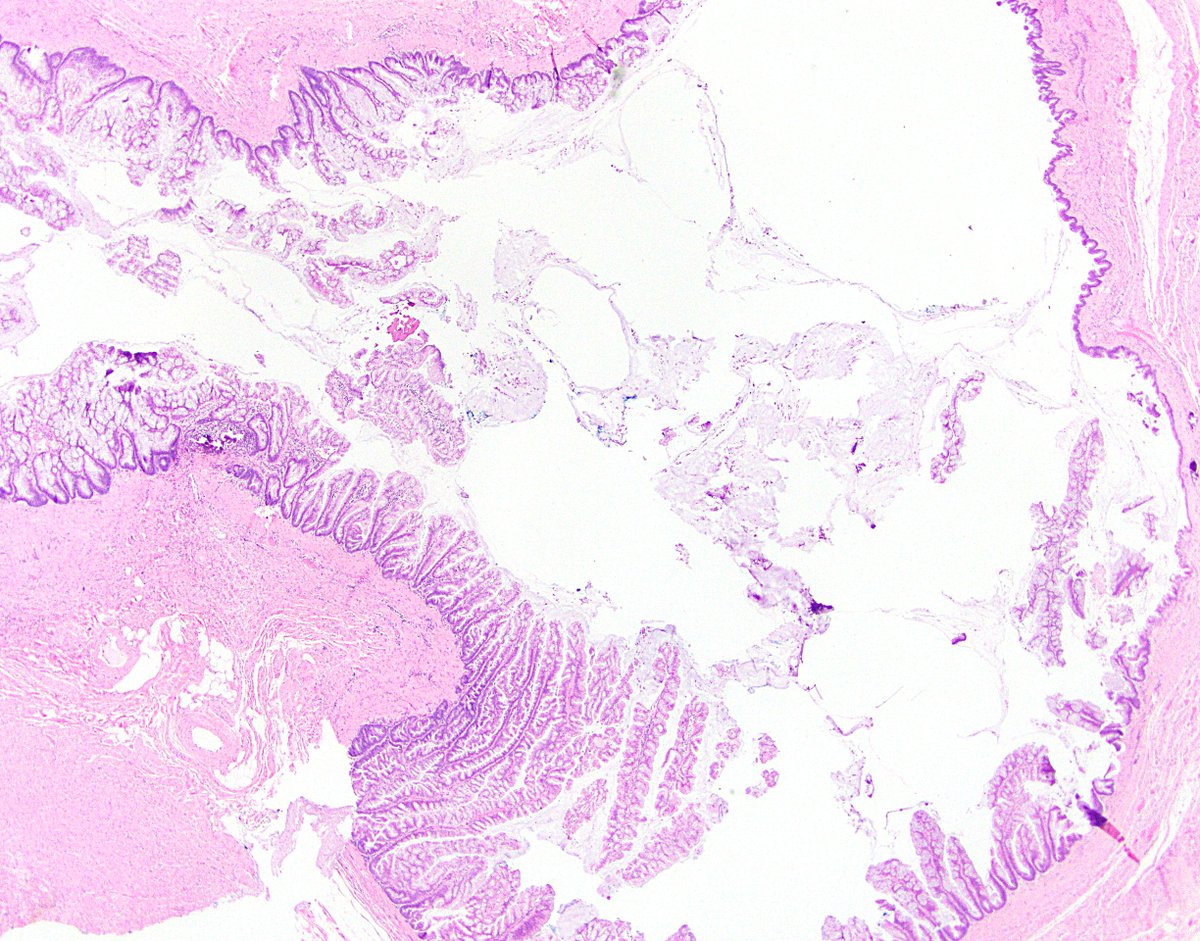

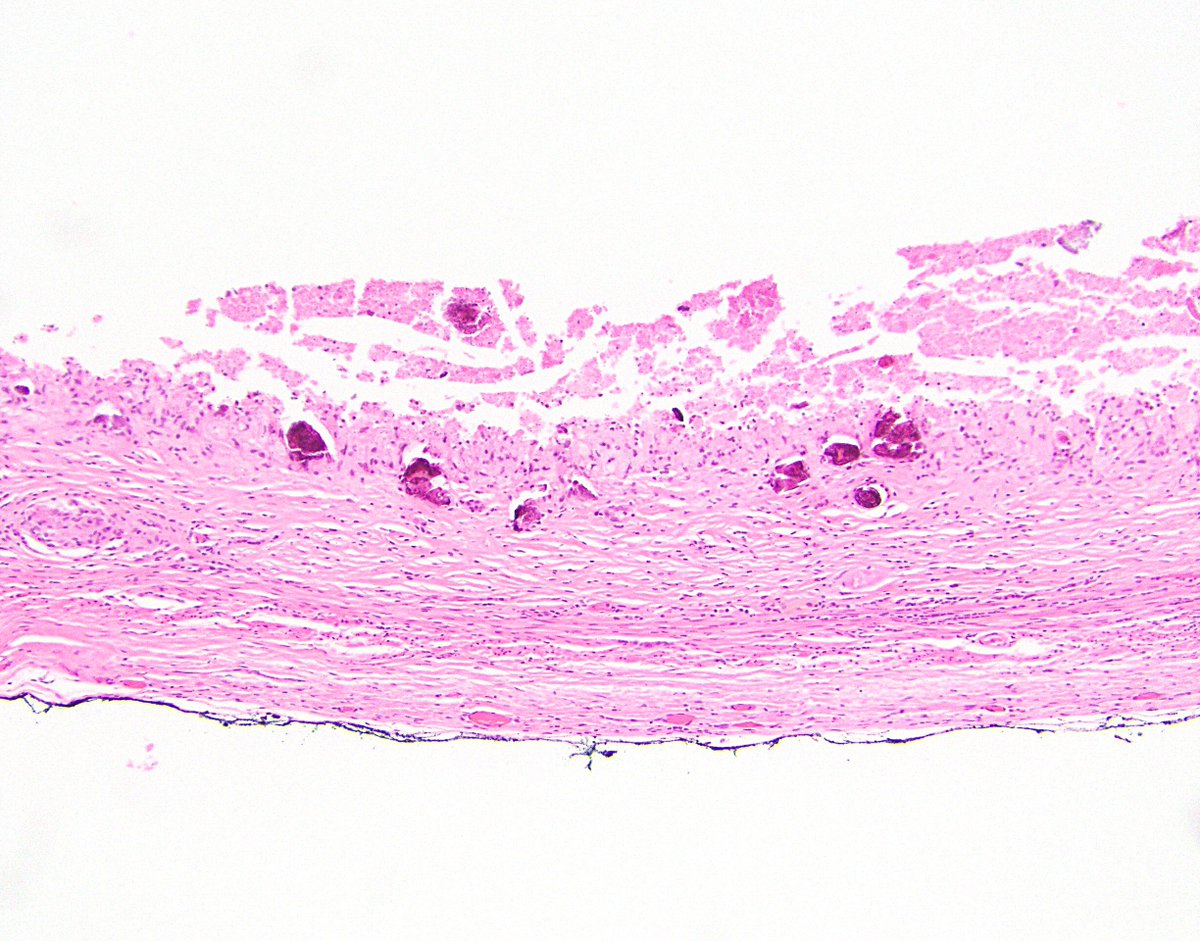

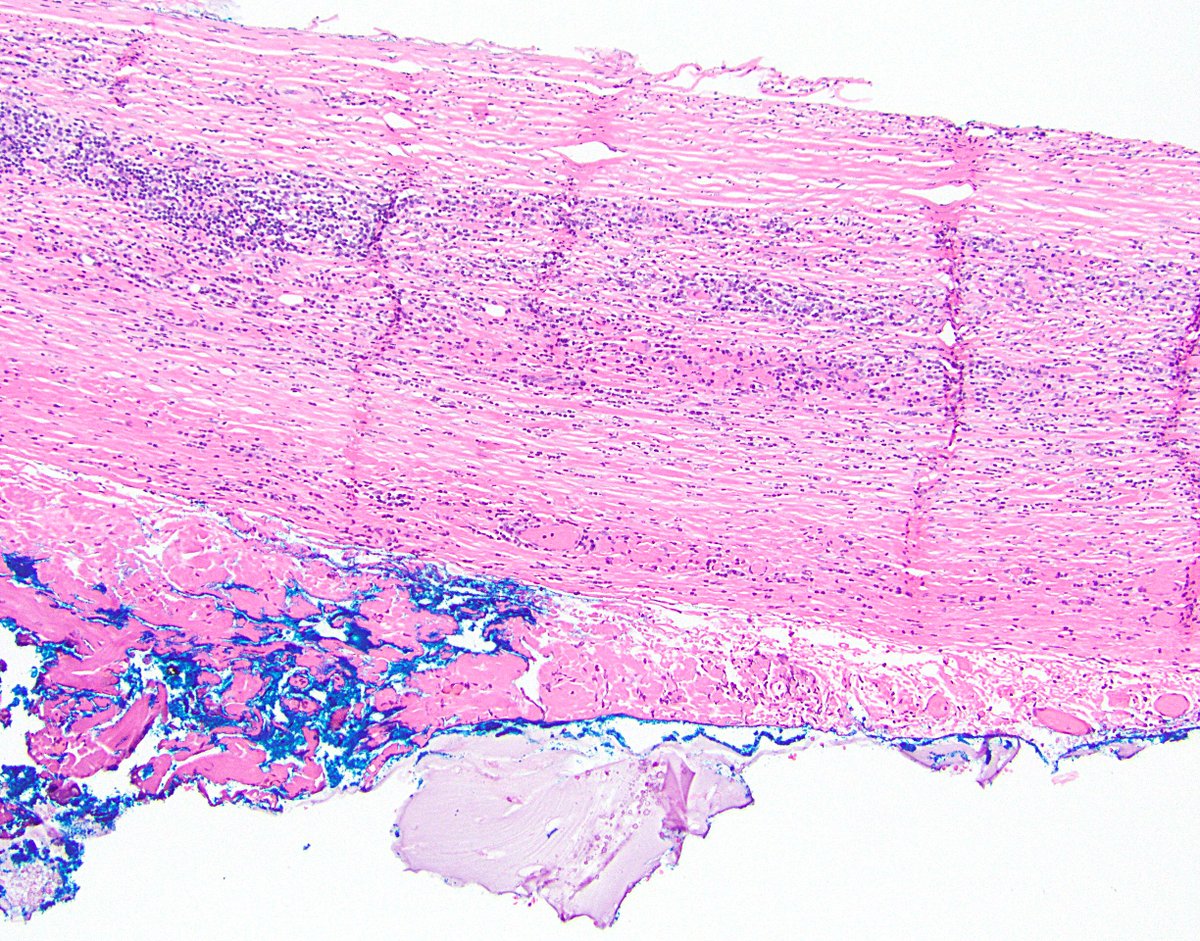

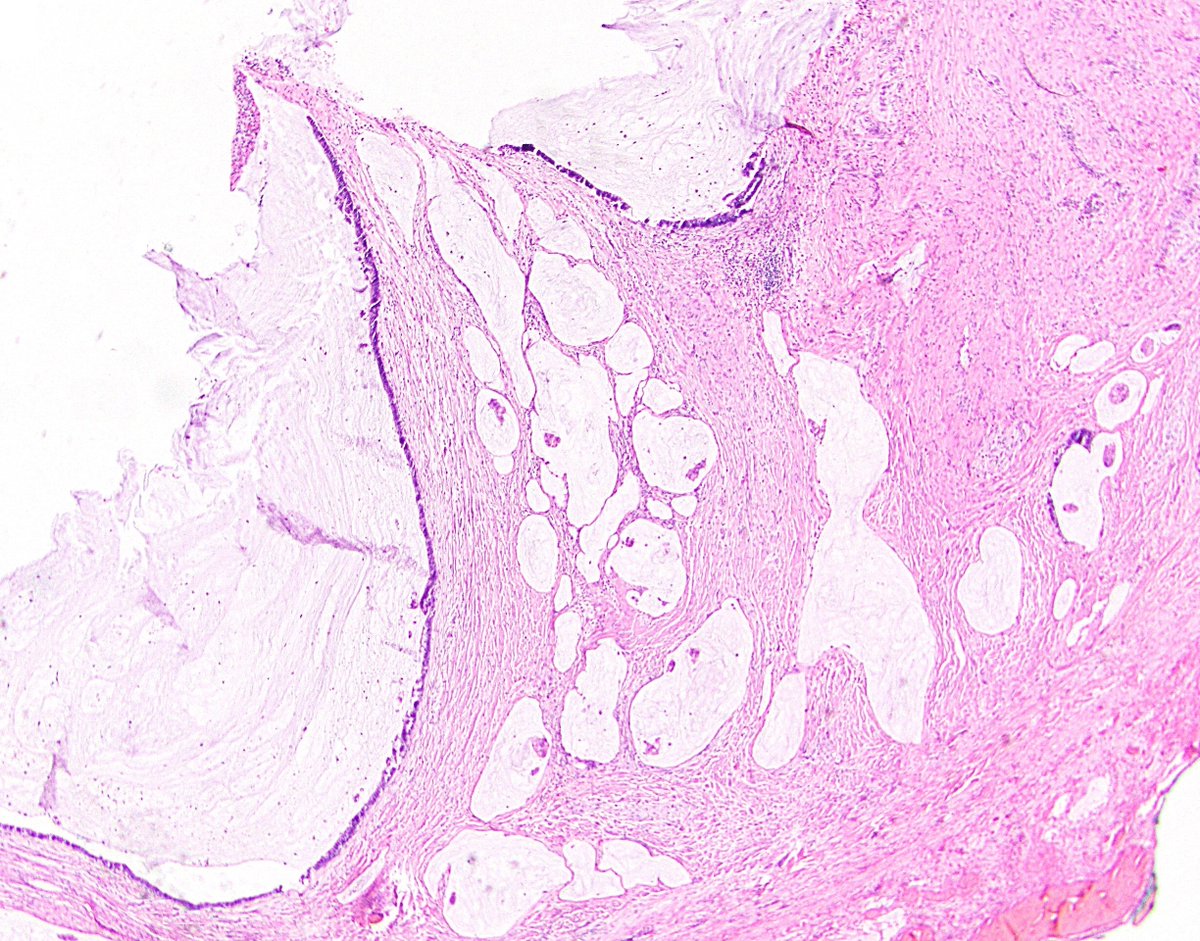

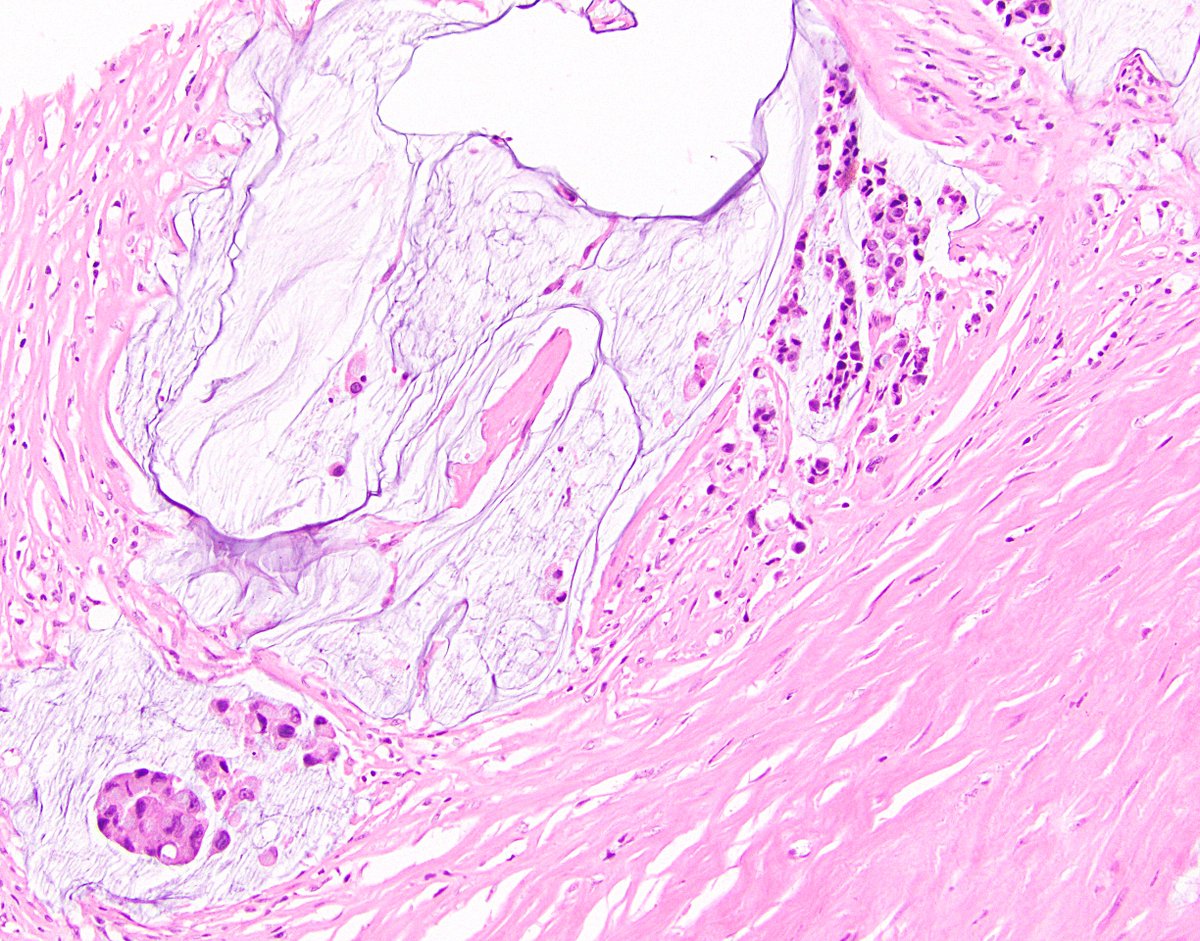

9/ 4. Dissection of acellular mucin in wall. This is another way that LAMNs can spread, with the mucin seeping its way into and through the wall. This can lead to perforation without the pushing epithelium having done most of the dirty work.

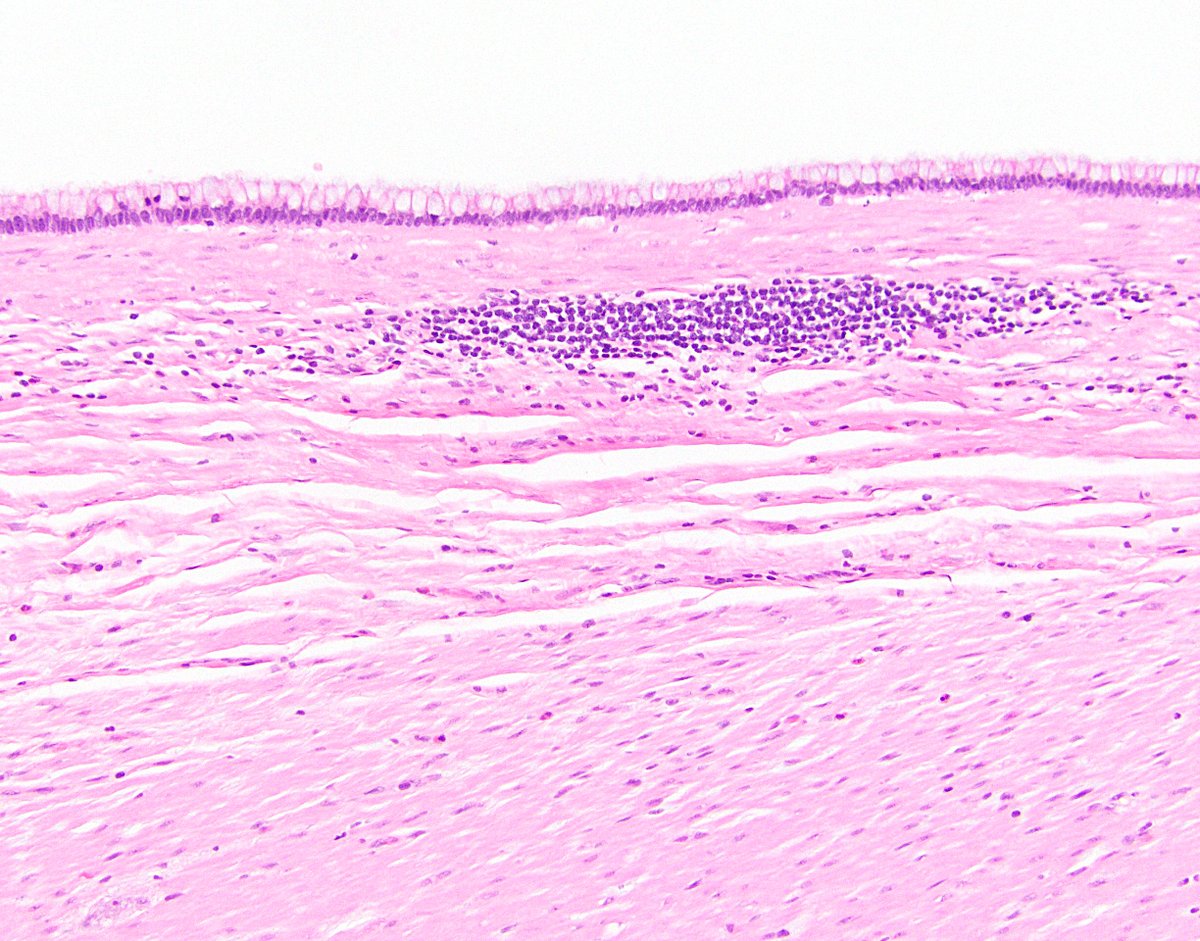

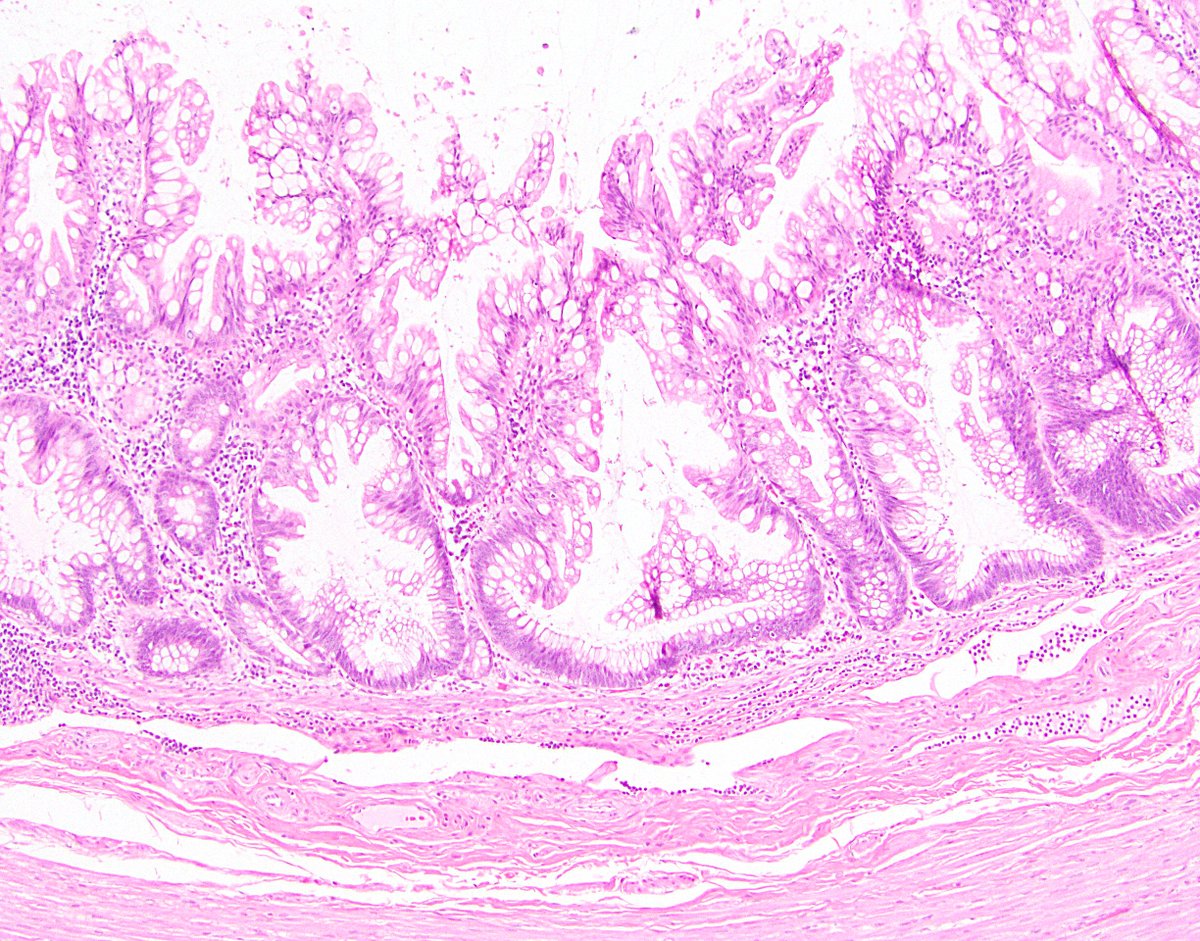

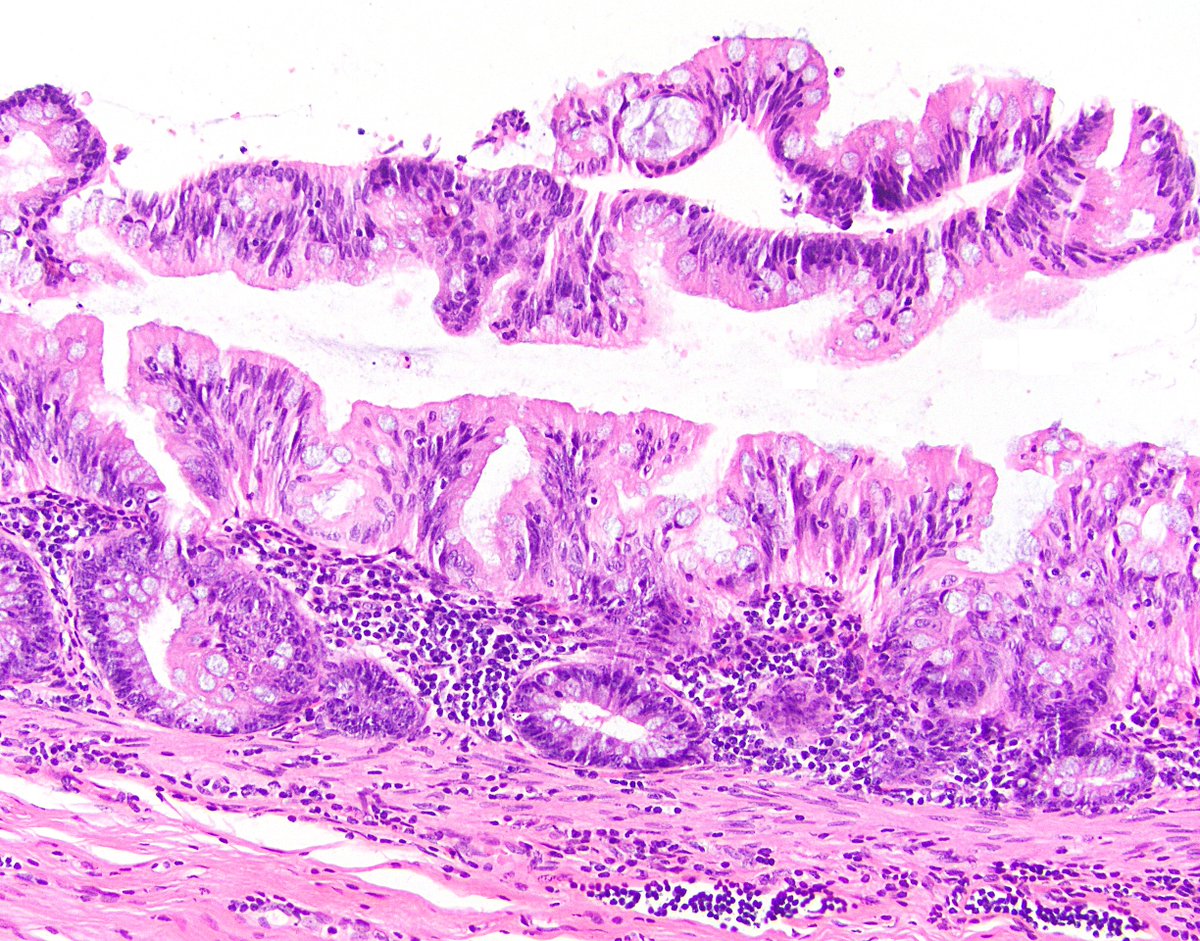

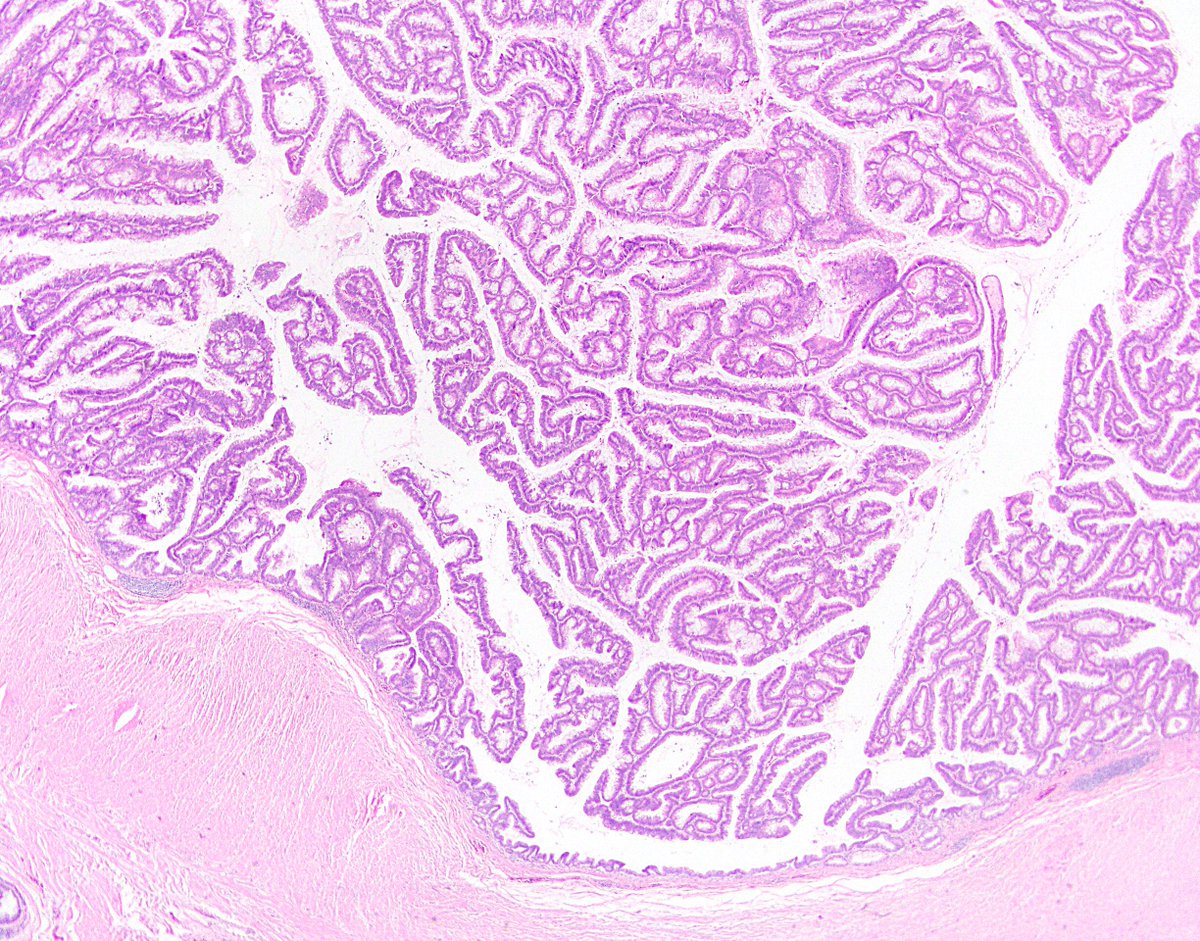

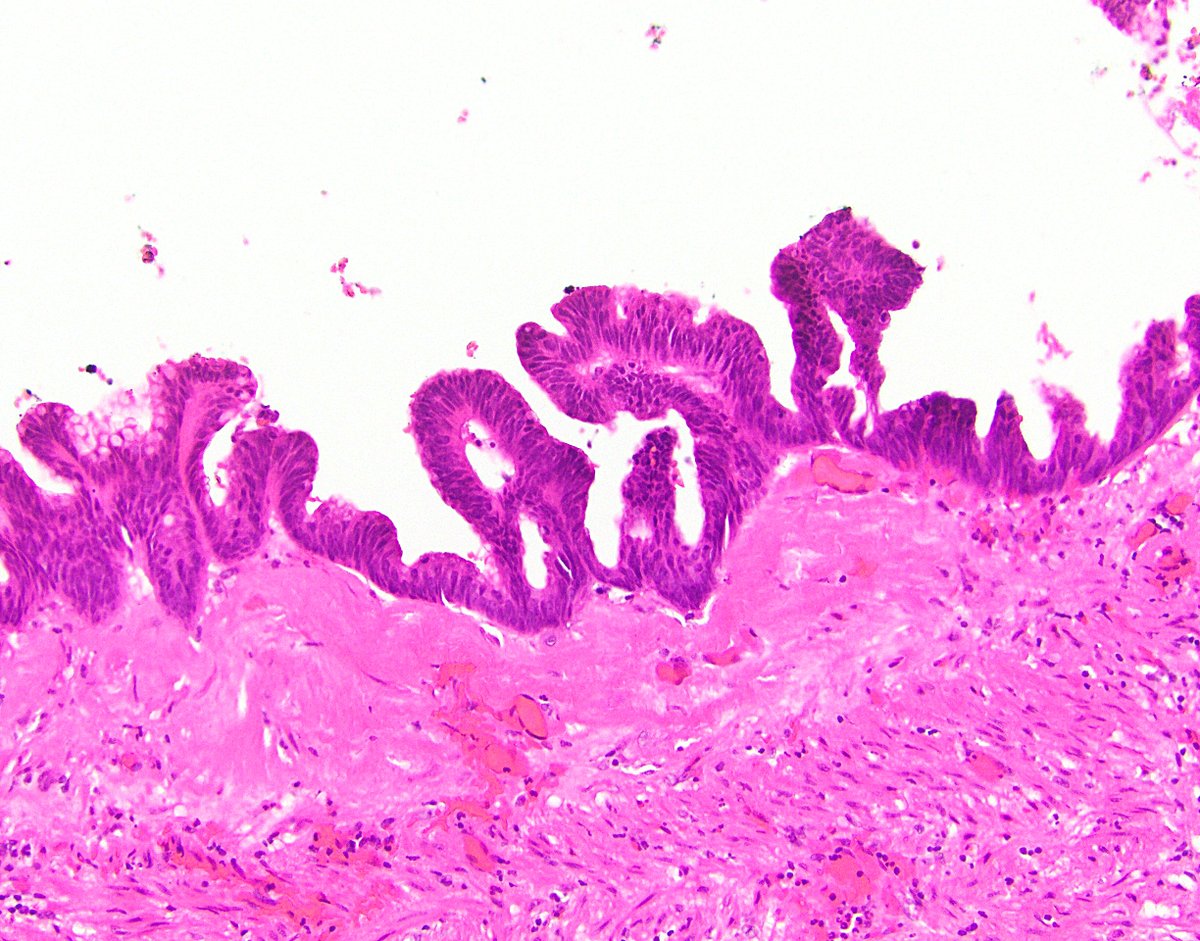

10/ 5. Undulating or flattened epithelial growth. This is basically always seen, as it’s how LAMNs typically look. The epithelial surface may be quite undulating or villiform (I’ve also seen it look serrated), or rather flat.

11/ Side note 2: As LAMNs are neoplasms, the epithelium is dysplastic by definition. It is of course low-grade, but sometimes it’s so bland (or so hidden by the intracellular mucin) that it looks like “no-grade” dysplasia.

12/ 6. Rupture of appendix. This is the bad thing that LAMNs can do. If they make their way beyond the appendix, the epithelium can potentially seed the peritoneum and produce copious mucin, a morbid process known as pseudomyxoma peritonei.

13/ 7. Mucin and/or cells outside appendix. This of course is the consequence of appendiceal rupture (subcriterion 6) or potentially dissecting acellular mucin (subcriterion 4). Therefore, the 7 subcriteria are not generally mutually exclusive; most LAMNs will have at least 2.

14/ Now that we’ve discussed definitions, let’s talk terminology. Many other terms have been applied to LAMN throughout history, including mucinous cystadenoma, mucinous adenoma, borderline tumor, and mucinous tumor of uncertain malignant potential. Ref: https://bit.ly/3rj6uvr ">https://bit.ly/3rj6uvr&q...

15/ “LAMN” was introduced in 2003 and has been officially adopted by the WHO, the PSOGI, the AJCC, and the pathology community at large. There are still some scenarios where some pathologists will use some of the other terms. Refs: https://bit.ly/3eg8YXT ,">https://bit.ly/3eg8YXT&q... https://bit.ly/3sPeiVV ">https://bit.ly/3sPeiVV&q...

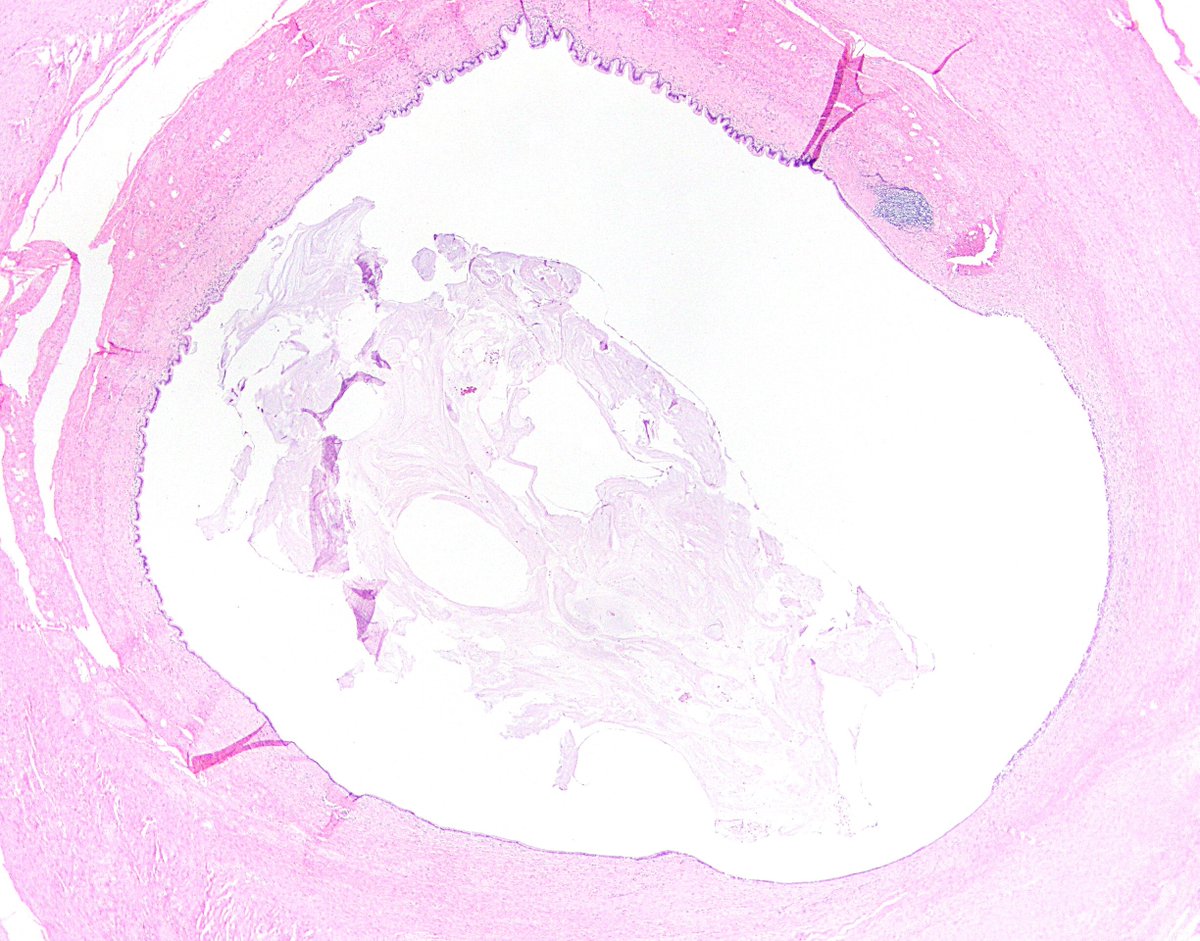

16/ Side note 3: The term “mucocele” is a clinical descriptor for a dilated, mucin-filled appendix. It’s fine as a clinical term and acceptable as a gross term, but it’s not a diagnosis and should not be used as a top-line interpretation in a pathology report.

17/ Side note 4: I pronounce LAMN “lamm-in,” but some people pronounce it “lamm” (lamb?), with the N silent. How do you pronounce it?

18/ Clinically, LAMN can present in a variety of ways. Somewhere around half of patients may present with abdominal pain (though not usually in an “acute appendicitis” sort of way). Roughly one third may be incidental (found on imaging, colonoscopy, etc.)

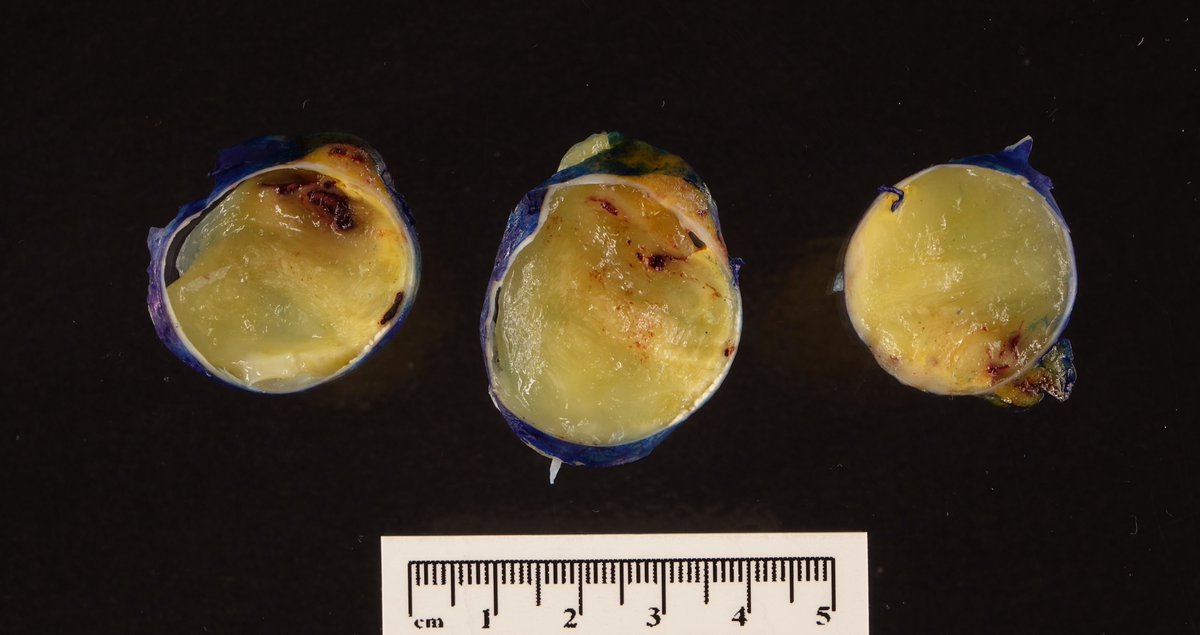

19/ Grossly, LAMN looks about how you’d expect -- namely, “gross.” Part or all of the appendix is dilated and filled with mucin (a mucocele).

20/ It’s a good idea to ink the serosa, helping you distinguish between true serosal mucin and dragging artifact microscopically. Also, inspect carefully for perforation, and submit the whole thing. Yes, even if it’s huge.

21/ I covered most of the histologic features of LAMN earlier, in definitional criteria. One additional important feature is that LAMN usually obliterates the lamina propria and the normal appendiceal crypts. If you see those, hesitate before calling it a LAMN!

22/ Also, sometimes a “mucocele” will have a thin, fibrotic wall, mural calcifications, and/or a histiocytic reaction obliterating the epithelium. Look closely in your million sections -- these are almost always LAMN, and there should be scant residual epithelium somewhere.

23/ Does the LAMN extend to the proximal mucosal surgical margin? No big deal! Studies have shown that it doesn’t grow into the colon or recur. You may have to convince the surgeon that further surgery isn’t necessary. Ref: https://bit.ly/2PoXnLt ">https://bit.ly/2PoXnLt&q...

24/ Another important point about LAMN is that it does not exhibit lymphovascular or perineural invasion. It’s just not that kind of malignancy! It really can only progress by rupturing the appendix and seeding the peritoneum.

25/ One thing I wonder about LAMN -- can it serve as a precursor to “true adenocarcinoma”? Some people think yes, some think no. I’ve seen a handful of pretty convincing cases, but the jury is still out. Of course, molecular might be needed to truly answer that question.

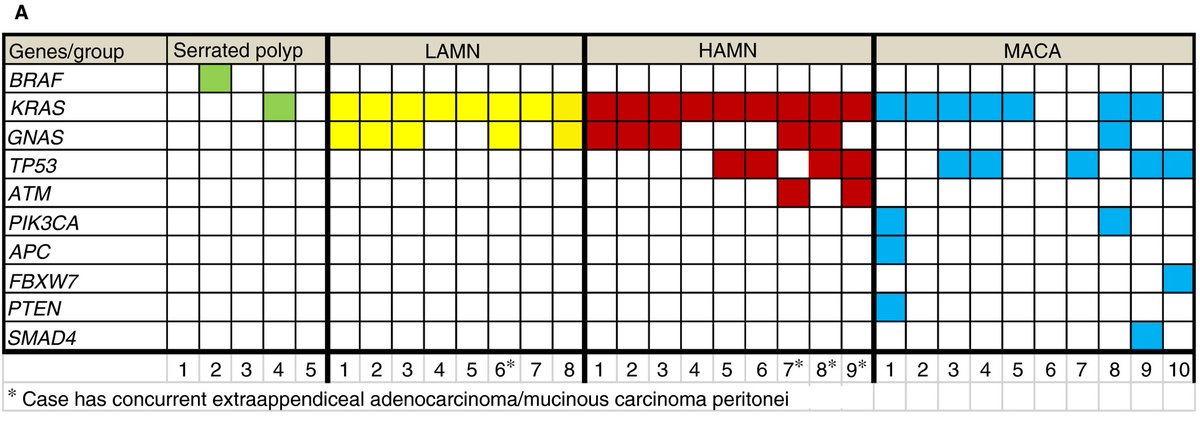

26/ The main molecular finding in LAMN is KRAS and GNAS mutations (Ref: https://bit.ly/3kXoFod ).">https://bit.ly/3kXoFod&q... GNAS is rare in appendiceal mucinous adenocarcinoma (and I wonder if most reported cases were actually exploded LAMNs). So ... who knows. Image ref: https://bit.ly/3riGYq8 ">https://bit.ly/3riGYq8&q...

27/ Now that we’ve covered diagnosing LAMN, let’s get into staging it. In the USA, we use the 8th edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging criteria. It’s the same system used for appendiceal adenocarcinoma, but there are some twists and turns ...

28/ In the appendix system, pT1 means the tumor involves submucosa, and pT2 means it involves muscularis propria. However, neither of these apply to LAMN! Instead, there’s pTis(LAMN) for “no-risk” LAMNs confined by the muscularis propria.

29/ However, pT3 (mucin or cells involve subserosa or mesoappendix) applies to LAMN. Are LAMNs confined to the appendix but deeper than pTis really at risk of progressing? Very sparse data (a case here, a USCAP abstract there) seem to say yes, but I’m not convinced juuust yet.

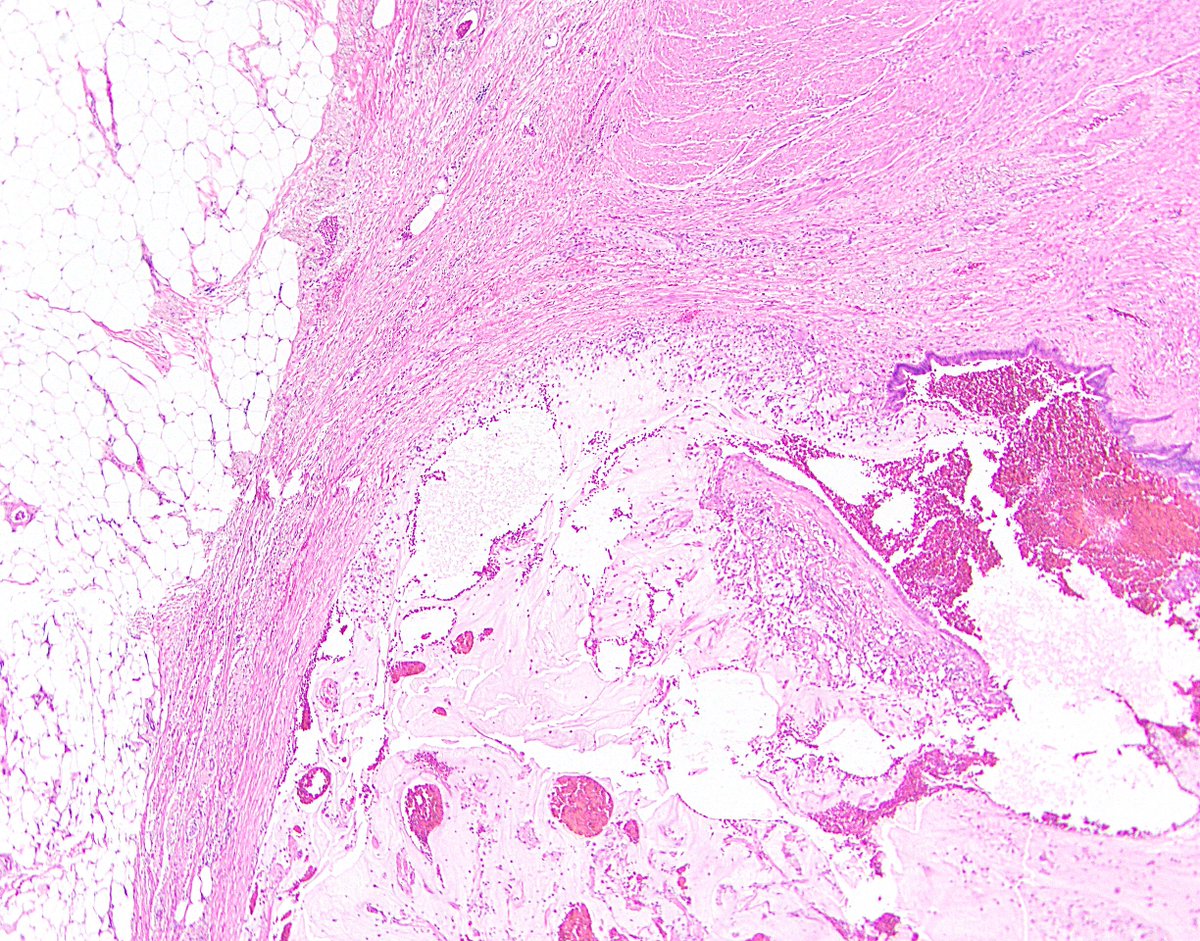

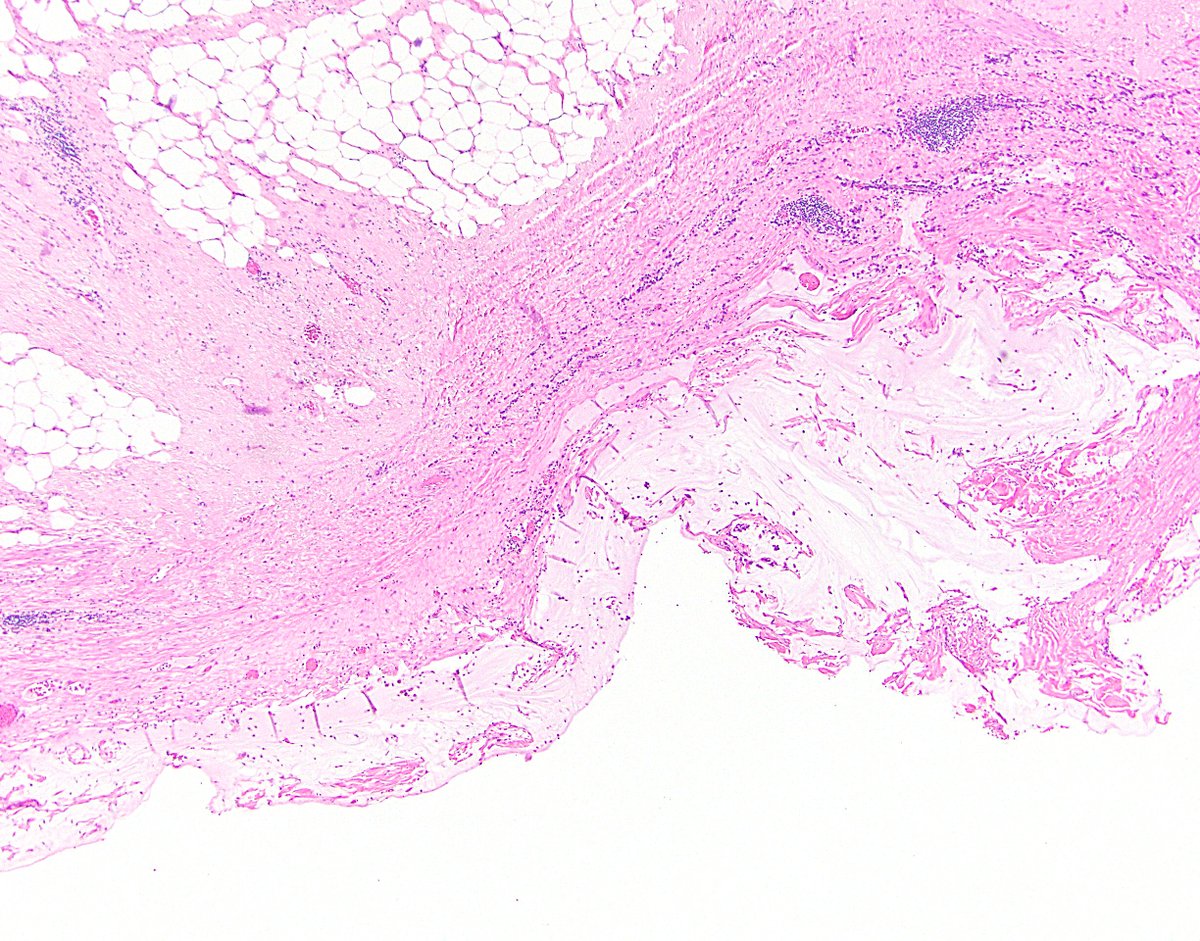

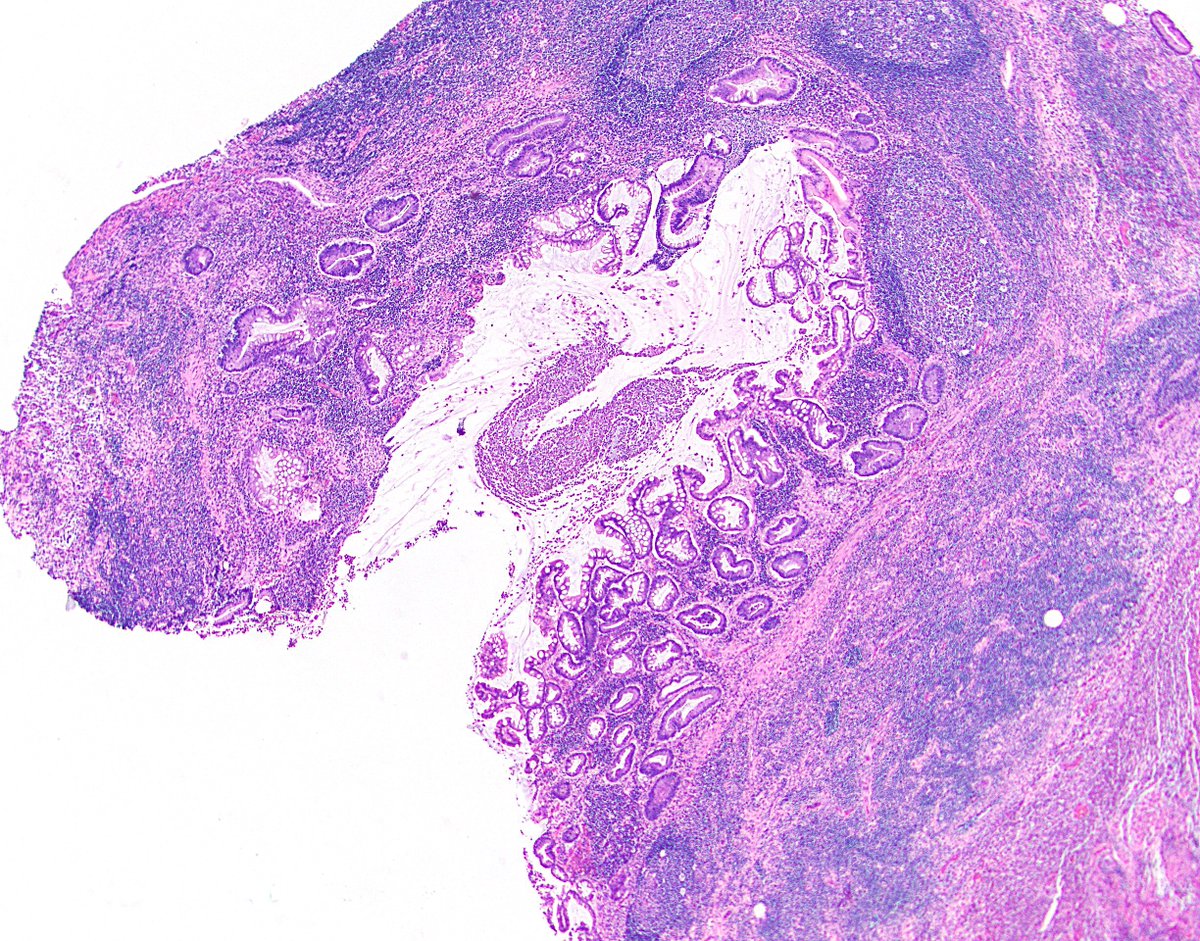

30/ pT4 is where things really start to get important. For LAMN, this means epithelium or mucin at/beyond the serosal surface. This usually means the appendix blatantly perforated, but sometimes the LAMN or the mucin can subtly squeeze through, so be alert and look carefully.

31/ Side note 5: If you’re wondering whether mucin made it beyond the serosa via perforation (in the patient, pic 1) or via knife carry-over (in the gross room, pic 2), look for inflammation and fibrovascular tissue in the mucin. If you see it, it’s likely true pT4.

32/ pT4a means the tumor has breached serosa and now is technically in the peritoneal cavity. This is the most common pT4 situation. pT4b means the tumor extends into another organ. I’ve very rarely seen it directly extend into the small bowel or etc.

33/ Of course, pT4b in spirit means the LAMN breached two serosal surfaces. Mural disease tracking up the appendix and directly proceeding into the wall of the cecum or colon that way shouldn’t count, in my opinion (though it technically might, depending on who you’re debating).

34/ Next is N-category staging (pN0, no nodes positive; pN1, 1-3 positive; pN2: 4+ positive). I mentioned earlier that LAMNs don’t exhibit LVI, so does this even apply to LAMN? Mostly no. I’ve spoken to people who claim to have seen LAMNs involving nodes, but I myself have not.

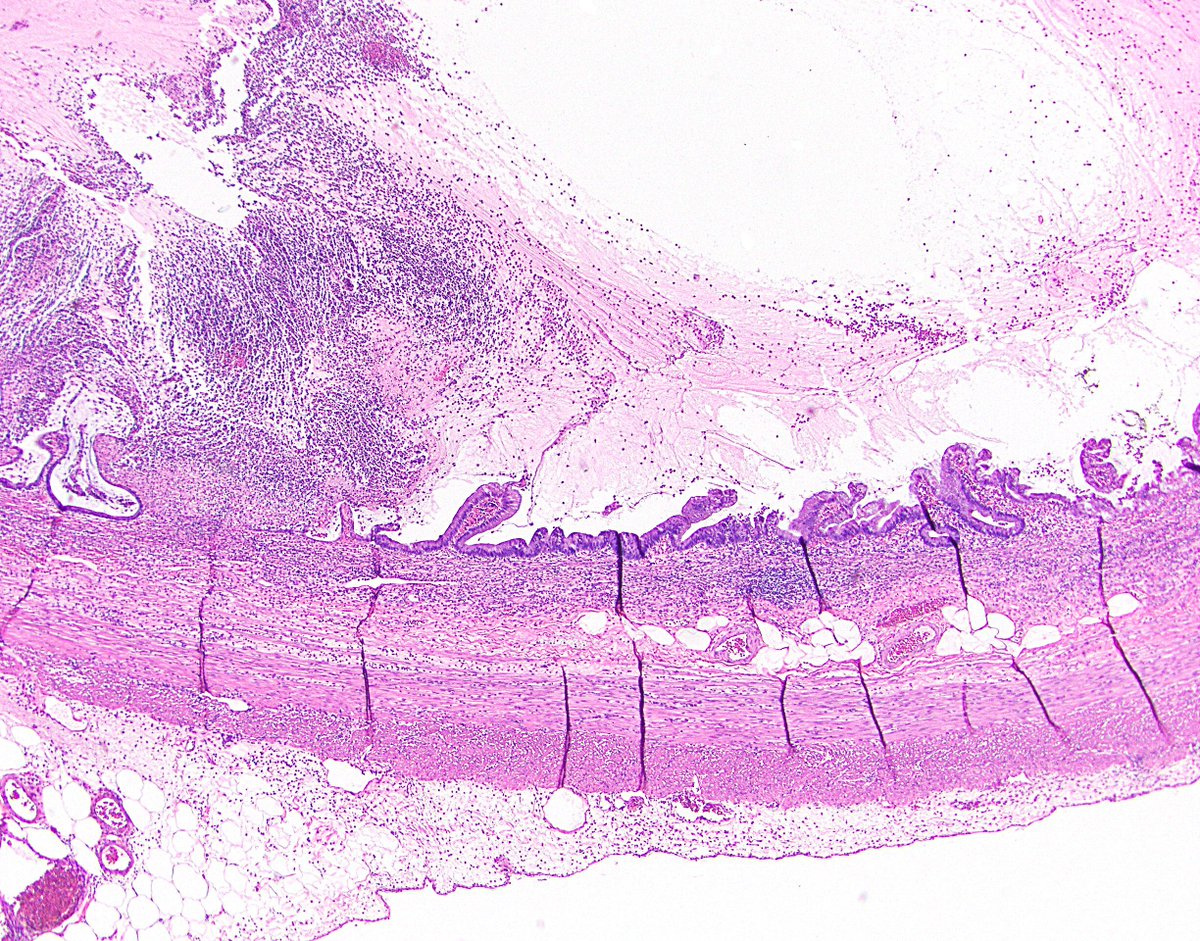

35/ In contrast, M-category staging is hugely important. To qualify, the disease must be distributed throughout the peritoneum. A little pT4 disease dripping into the right lower quadrant alone does not count.

36/ LAMNs only involving the RLQ, without frank peritoneal disease, do have an increased risk of recurrence/progression, but it appears relatively small. Again, this does not qualify as M-category disease. Ref: https://bit.ly/3riH29m ">https://bit.ly/3riH29m&q...

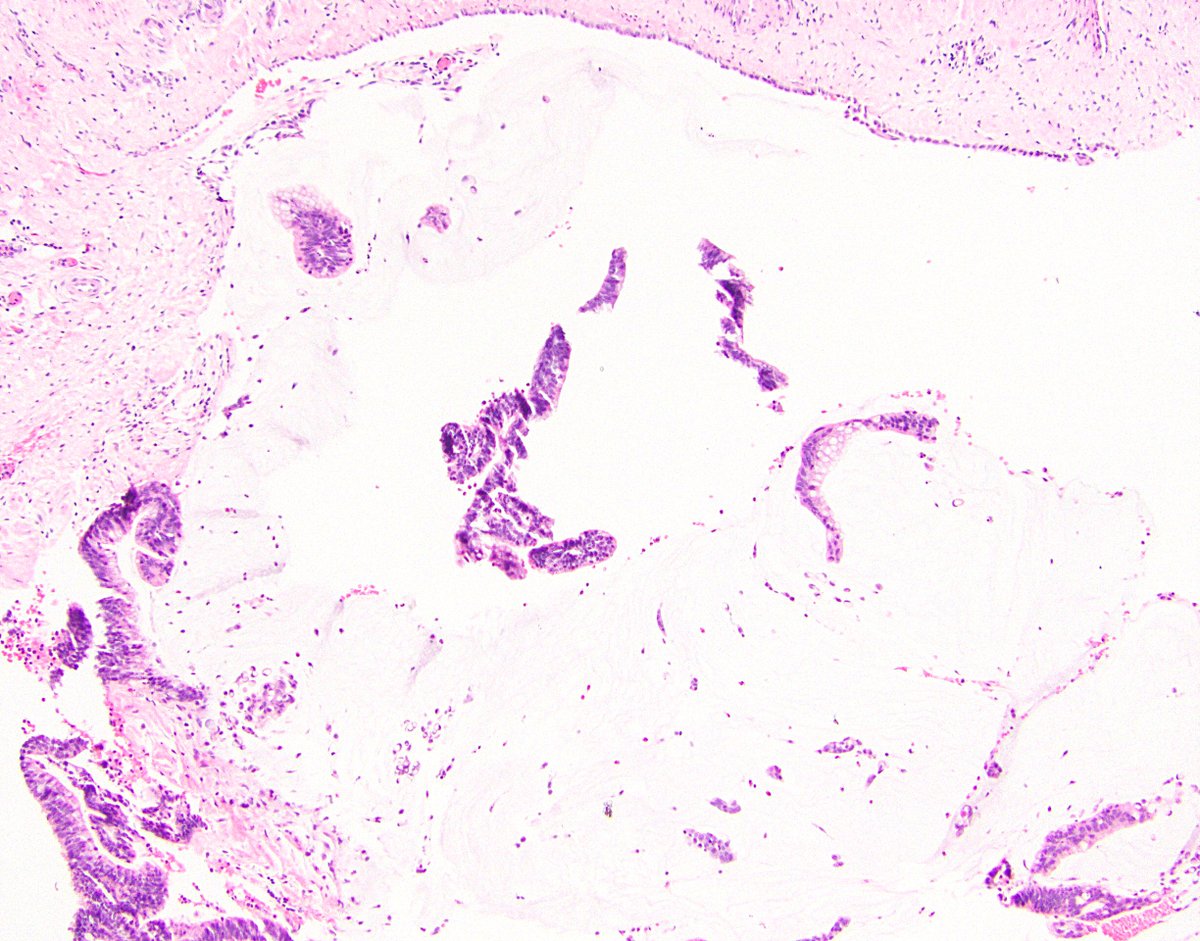

37/ pM1a disease is acellular mucin in the peritoneum. This pretty much only counts for LAMN, since adenocarcinoma would be cellular. Of course, even acellular mucin has to be produced by something, so there’s presumably tiny embedded bits of LAMN epithelium somewhere.

38/ pM1b disease is cellular mucin in the peritoneum. The AJCC states to grade this and more or less indicates to use the Davison criteria. This is indeed what many people use in practice. The criteria are as follows ...

39/ Look for destructive invasion, high-grade cytology, high cellularity, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion. None of these? Grade 1. At least one? Grade 2. Signet ring cells? Grade 3. (Unsurprisingly, pM1b LAMNs are often grade 1 here.) Ref: https://bit.ly/2O0sX1K ">https://bit.ly/2O0sX1K&q...

40/ Finally, pM1c is metastatic disease outside the peritoneum. In other words, distant metastasis (liver parenchyma, etc.). Since LAMN doesn’t really spread via vasculature, this only applies to adenocarcinoma. If a LAMN pops up in the lung, it quite likely wasn’t a LAMN!

41/ One rare exception to this actually is LAMN involving the pleura or lung parenchyma (Ref: https://bit.ly/3ebBXfo ,">https://bit.ly/3ebBXfo&q... case 4). Maybe it got there through a weak spot in the diaphragm? Maybe those were actually low-grade conventional adenocarcinomas? LAMN continues to confound.

42/ Also, don’t mistake studding of the peritoneal serosa (and the sequelae) for hematogenously metastatic disease. LAMNs often swim their way over to the ovaries and push their way in, for instance, but I would argue they don’t get there via the “pM1c” route.

43/ OK, so we’ve defined pM disease in LAMN, but what does it really *mean*? Well, it translates to pseudomyxoma peritonei, which PSOGI defines as “intraperitoneal accumulation of mucus due to mucinous neoplasia characterized by the redistribution phenomenon.”

44/ Pseudomyxoma typically (but not always) arises from an appendiceal mucinous neoplasm. Clinically, it causes abdominal symptoms such as pain, bloating, pressure, and/or discomfort. Some patients may experience weight loss.

45/ When evaluating pathology specimens from pseudomyxoma, keep the Davison criteria in mind and look closely. Primary disease and peritoneal metastases are often grade-concordant, but not always. (If not ... was the entire appendix submitted? If not, maybe something was missed.)

46/ When signing out these cases, I personally don’t say “peritoneum involved by pseudomyxoma peritonei” (or etc.) I just describe what I see. Example: “Peritoneum, biopsy: Low-grade (grade 1) cellular mucin, consistent with involvement by patient’s known LAMN.”

47/ Side note 6: I don’t like the term pseudomyxoma peritonei, but it’s entrenched. Historical synonyms/alternatives arguably haven’t been great either: low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei, disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis, peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis, etc.

48/ Of course, absolutely no offense to anyone who proposed any of those terms when crafting their excellent studies. I certainly don’t have a better suggestion. It’s just hard to describe the weird behavior of the weird thing that is LAMN.

49/ So what does all this mean for patients? If a LAMN is appendix-confined, the patient is likely cured (again, pT3 disease remains iffy). If the patient has pT4a disease or RLQ mucin, they may require more therapy. If they have pseudomyxoma, they definitely need more therapy.

50/ Standard therapy these days is peritoneal debulking (the surgeon goes in, scoops out the mucin, and looks very closely at the peritoneum, stripping off anything that even sort of looks like it could be involved by LAMN) followed by HIPEC.

51/ HIPEC is heated intraperitoneal chemotherapy. They infuse the peritoneum with warmed-up chemo. As you can imagine, patients often have a rough course after debulking and HIPEC, but it does present a chance for prolonged disease-free survival and maybe even cure.

52/ Some patients will also get systemic chemo (FOLFOX, etc.), but this may not help much. NCCN Colon Cancer guidelines discuss debulking/HIPEC alongside peritoneal carcinomatosis, and they mention pseudomyxoma but don’t specifically talk about LAMN. Ref: https://bit.ly/2O1IRsS ">https://bit.ly/2O1IRsS&q...

53/ In the last part of this Tweetorial, let’s talk about differential diagnosis. Lots of things can mimic LAMN, and even though we now have pretty specific criteria for its diagnosis, this challenge comes up not infrequently.

54/ 1st, reactive hyperplasia. The appendix gets beat up a lot, and the reactive changes in the mucosa can look very hyperplastic or serrated. There’s still plenty of lamina propria and crypts, though. I wonder whether the rare “hyperplastic polyp” of the appendix overlaps here.

55/ 2nd, diverticula. These can undergo reactive change, as just mentioned. They’re also weak and rupture easily, potentially spilling mucin beyond the appendix. However, there’s no neoplasm, so the patient is not at risk of progression. Don’t raise the specter of pseudomyxoma!

56/ 3rd and sometimes trickiest, serrated polyp (per PSOGI; sessile serrated lesion per WHO). These look like their serrated cousins in the colon, with booting and etc. Often circumferential, may have cytologic dysplasia, usually plenty of lamina propria still.

57/ If a serrated polyp is completely excised, then like LAMN, there’s no risk of progression, and mixing up the two isn’t a catastrophe. Also, I’ve seen rare cases that blur the line between serrated polyp and LAMN, or segue from one to the other. Help me, Obi-Wan Molecular!

58/ 4th, traditional serrated adenoma. This guy, or a related lookalike, can pop up in the appendix, though it hasn’t been published on too much. More likely to be confused for a serrated polyp than a LAMN, but definitely in the differential. Ref: https://bit.ly/3bgOOL8 ">https://bit.ly/3bgOOL8&q...

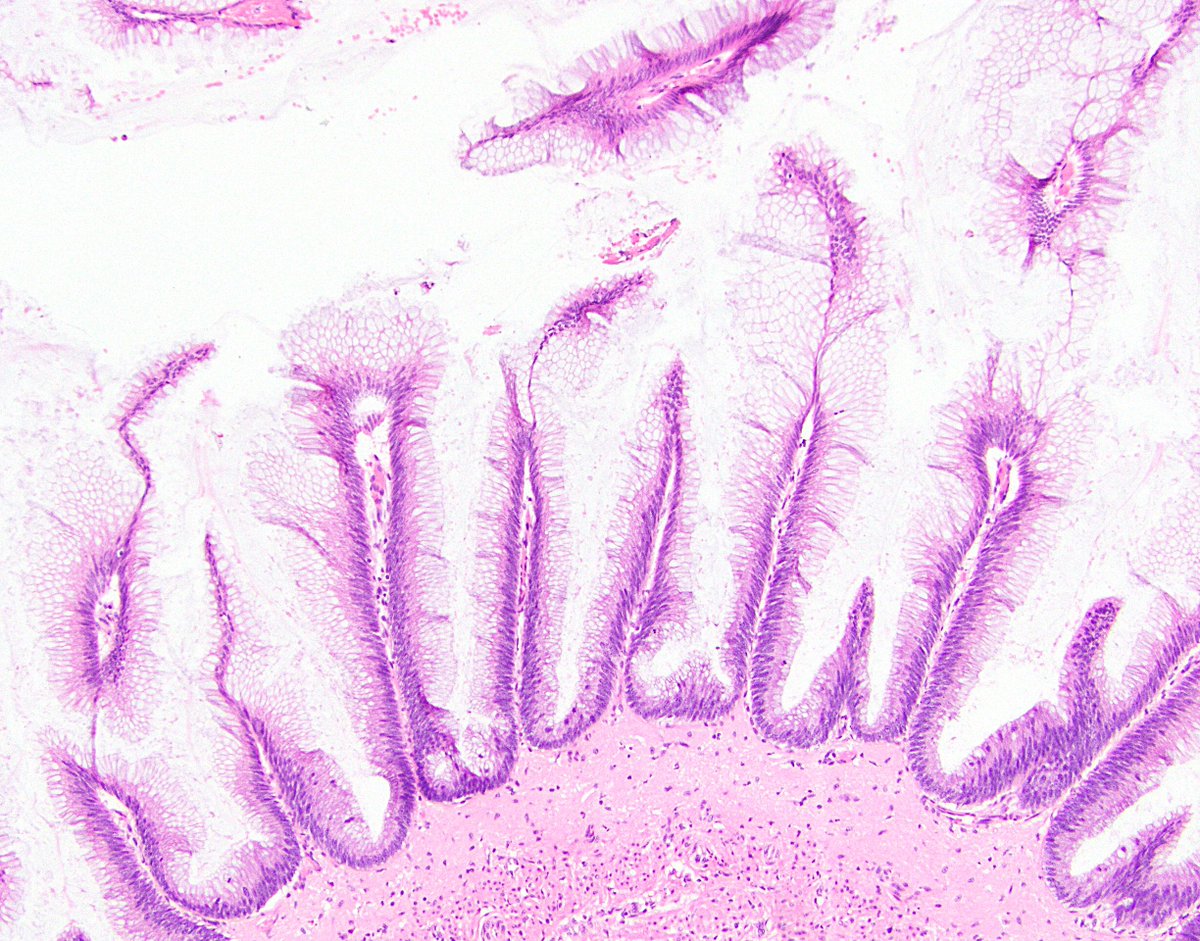

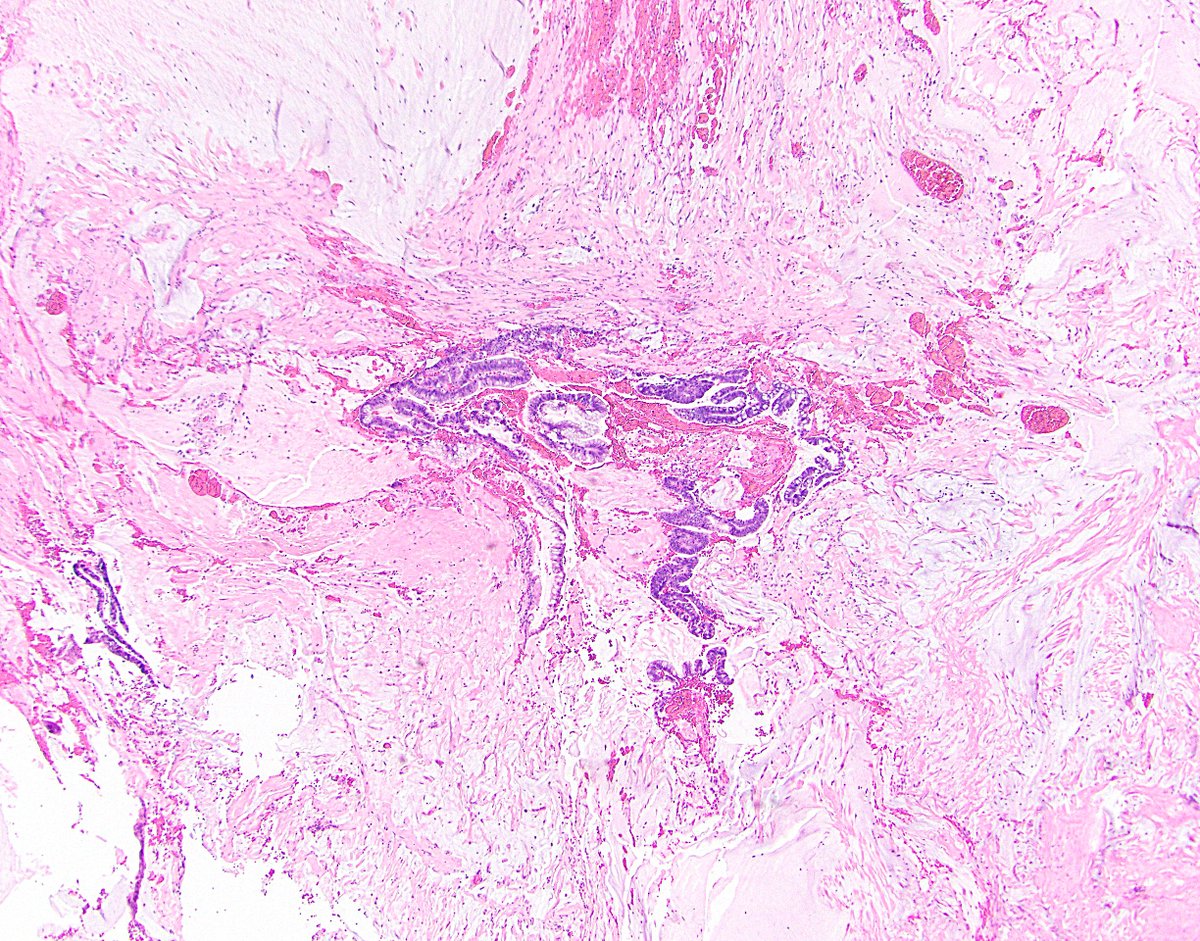

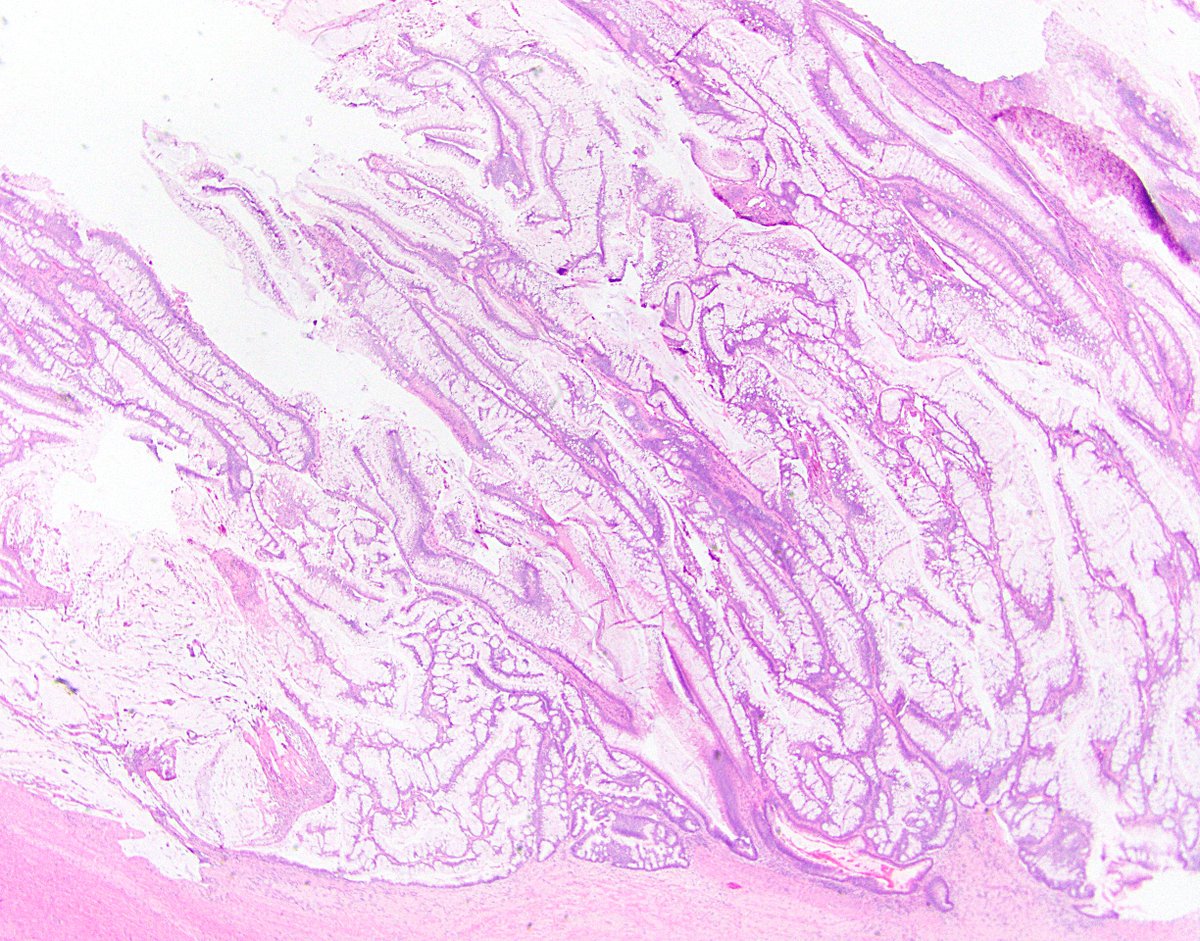

59/ 5th, tubulovillous adenoma. These can occur in the appendix, and they are often much more mucinous than their colorectal counterparts. If something seems too florid or cytologically striking to be a LAMN, consider TVA. Tubular adenomas are rare in the appendix outside FAP.

60/ 6th, HAMN. This rare, unsightly cousin to LAMN looks an awful lot like it at low power. By PSOGI criteria, if you’ve got something that fits LAMN criteria but has at least focal “unequivocal” high-grade dysplasia, it’s HAMN. It seems to behave the same biologically.

61/ 7th, mucinous adenocarcinoma. This can be the hardest, as advanced LAMNs can certainly evoke a sense of a traditional adenocarcinoma. The distinction is important, as adenocarcinomas can metastasize beyond the peritoneum, meaning systemic chemo is the way to go.

62/ The main clues for adenocarcinoma over LAMN: Look for trickling, not pushing, invasion. Look for single cells. Look for cytologic atypia beyond LAMN (though then maybe you’re at HAMN). Look for tumoral necrosis. Look for a non-mucinous component. Good luck!

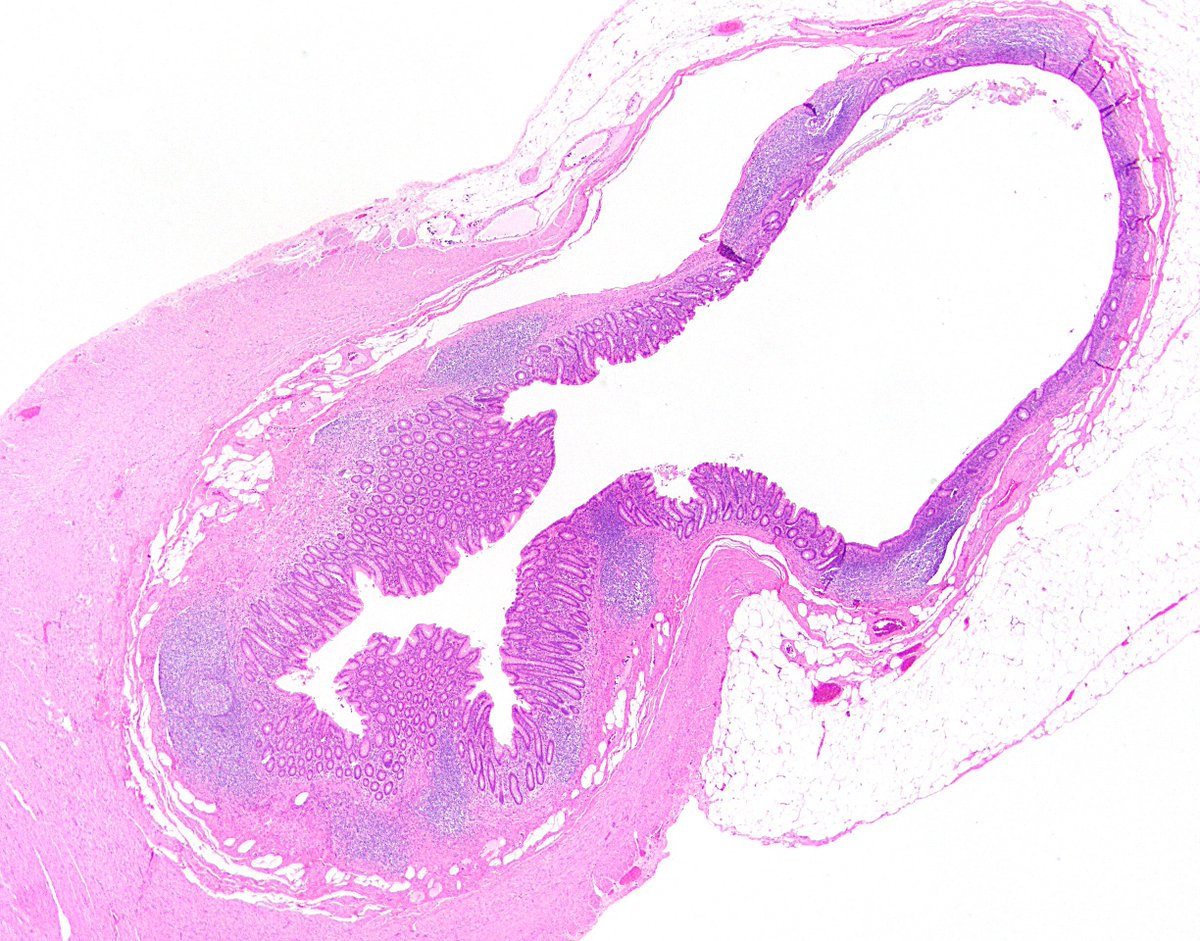

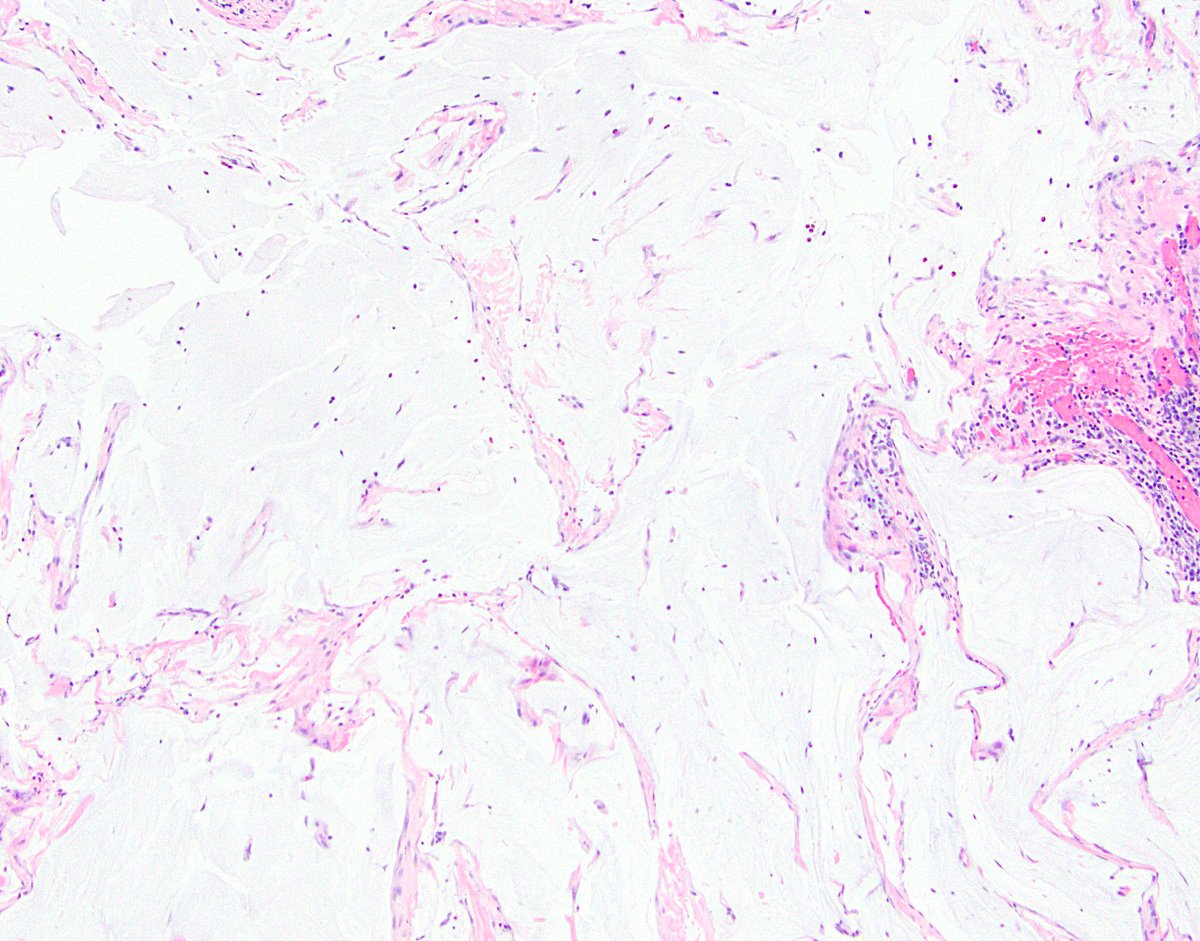

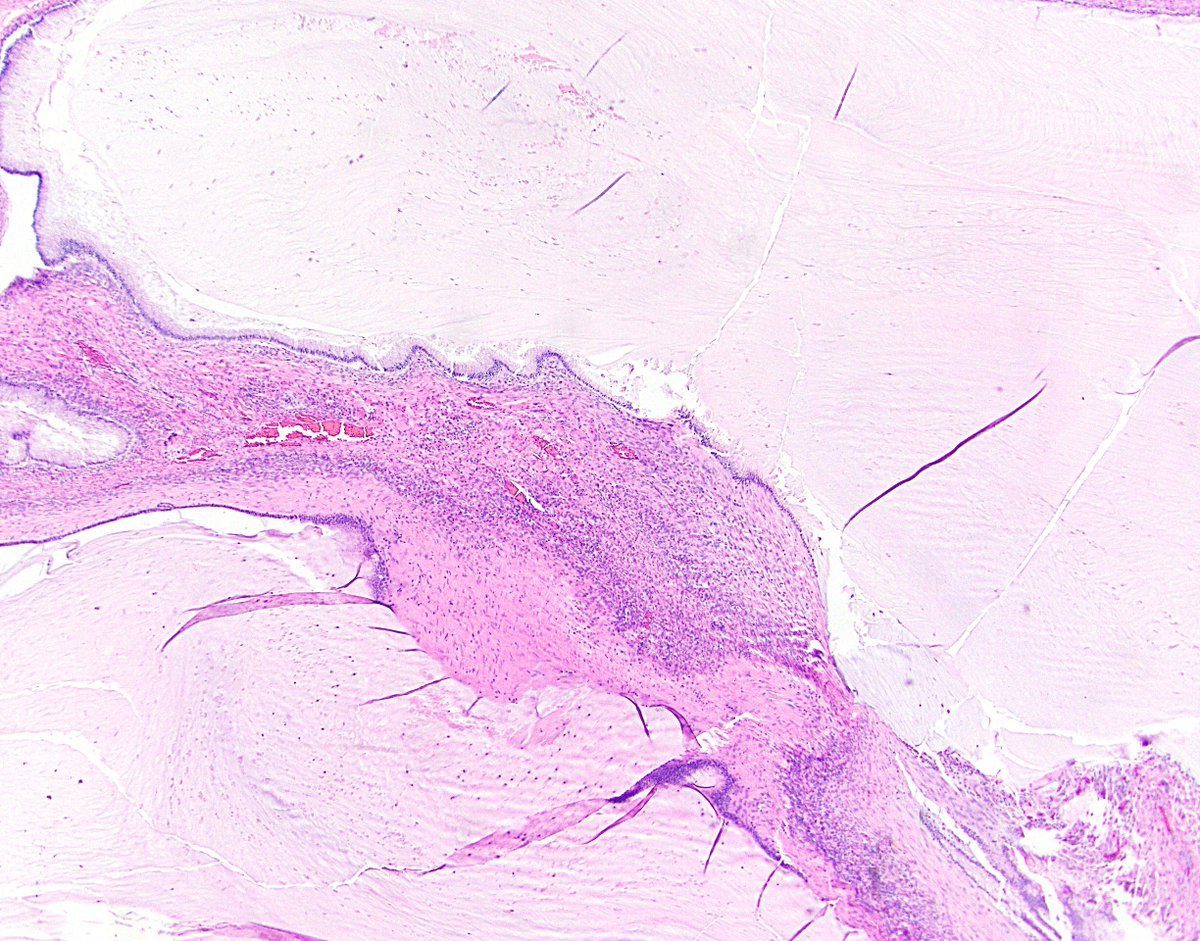

63/ And finally, for fun, remember that LAMN can coexist with other findings in the appendix. Here’s a LAMN with a neuroendocrine tumor, and a LAMN with some endometriosis. (I feel like I’m showing off vacation photos. Remember vacations?)

N64/ That’s all I got. Hopefully you are less confused now than you were before the Tweetorial, but if not, nobody would blame you. LAMN can be headache-inducing. Feel free to post any questions, and I will answer them as best I can. Thanks for coming along for the ride!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter