How do normative considerations influence causal thinking? A short thread on my new experimental paper with Eric Sievers, "Cause, & #39;Cause& #39;, and Norm" (preprint here: https://philpapers.org/rec/SCHCQA-2 ).">https://philpapers.org/rec/SCHCQ... It& #39;s got video!

To begin, take 30 seconds to watch the following animation, and then ask yourself the following question, which hereafter I& #39;ll call "CAUSED":

At the end, which shape caused the triangle to break -- the circle, the square, or both of them?

At the end, which shape caused the triangle to break -- the circle, the square, or both of them?

Many of you likely gave "the square" as your answer to CAUSED. But why? After all, there& #39;s a clear sense in which both shapes did just the same thing, and what happened to the triangle depended equally on both of them. So what makes the square stand out as cause of what happened?

The obvious answer is: the square stands out because it broke the rule by jumping out of turn. And some classic work by Josh Knobe gives us a neat way of understanding why this would lead the square to be identified as the cause of the triangle breaking.

For Knobe, to say that the square caused the triangle to break is to say that the triangle breaking depended counterfactually on something the square did. And the idea is that since the square broke the rules, its jumping onto the platform at the end is more salient than the /

circle& #39;s doing the very same thing, since the circle did what it was supposed to. This makes us identify the square more strongly than the circle as the cause of the triangle breaking. It explains why norm-violating agents are identified as more causal than norm-conforming ones.

But wait! Watch the video again and consider two more questions, again with "the circle", "the square", and "both" as the possible answers:

[BROKE] At the end, which of the shapes broke the triangle?

[BOUNCED] At the end, which of the shapes bounced the triangle into the air?

[BROKE] At the end, which of the shapes broke the triangle?

[BOUNCED] At the end, which of the shapes bounced the triangle into the air?

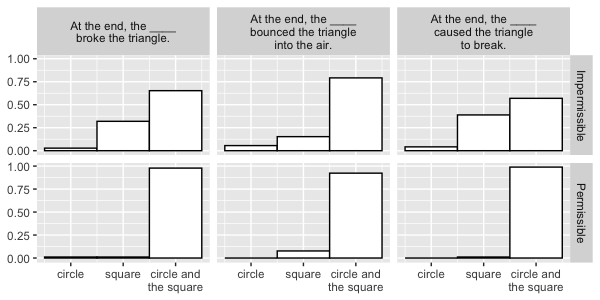

If you are like our experimental participants, many of you will have given *different* answers to these two questions: to BROKE you may have answered "the square", as you did with CAUSED; but with BOUNCED you are overwhelmingly likely to have answered "both of them".

And what makes this surprising is that BOUNCED is clearly a causal statement: roughly, to say that X bounced Y into the air is to say that, by bouncing, X caused Y to go up. But then why is agreement with *this* causal statement unaffected by the square& #39;s having broken the rules?

Eric and my paper presents a lot of findings that look just like this one: that is, we found very often that agreement with causal judgments that don& #39;t employ the *verb* "to cause" are unaffected by whether or not the agent violated a norm. https://philpapers.org/rec/SCHCQA-2 ">https://philpapers.org/rec/SCHCQ...

For example, here in more detail are the findings from the experiment just discussed, which included a condition in which the square& #39;s final jump was permitted, since it was given the (literal) green light to do so. Note the difference in how often "the square" was selected:

Likewise, here is an experiment in which (it is implied) two people both inject a mouse with poison, one following the rules while the other breaks them, and the mouse dies from the double does. Note that we did NOT say explicitly that either one injected anything into the mouse!

Again, the key finding here is that the judgment that an agent KILLED the mouse is affected by norm violation in the same way as the judgment that they CAUSED the mouse to die -- but the judgment that they INJECTED the mouse with poison, which is also causal, is not so affected.

What& #39;s going on here? Why are some causal judgments affected by norm violation while others are not? And what does this show about ordinary causal thinking? Our paper departs from Anscombe& #39;s observation that the VERB "to cause" is not the only word we use to talk about causing.

The simple thought was that if you want to investigate ordinary causal judgment, you ought to be looking at the full variety of ways in which it is expressed -- whereas most experimental work in this area uses ONLY sentences of the form "X caused ..." or "X caused Y to ...".

Additionally we noticed, as others have too, that the most common ordinary use of the verb "to cause" is in a context where we are out to assign *responsibility* for some (usually undesired) event. For more on this, check out this paper by Sytsma et al.: https://philpapers.org/rec/SYTCAA ">https://philpapers.org/rec/SYTCA...

And Eric and I argue that our findings support the conclusion that *this* is what best explains the influence of norms on causal judgment -- that is, that the influence arises when causal thinking is itself a kind of normative thinking, b/c tied to matters of praise and blame.

E.g., the reason why you say it is the square that CAUSED the triangle to break, and also that BROKE the triangle, is that to say these things is really to *blame* the square for this outcome -- and its having jumped out of turn makes it blameworthy in a way that the circle is& #39;t.

By contrast, the question of which shape BOUNCED the triangle into the air isn& #39;t read this way. Since this isn& #39;t something that we blame (or credit) either agent for, we interpret it as purely descriptive our evaluation of it isn& #39;t so affected by whether they broke the rules.

Likewise in our case where the mouse ends up dead: if someone was *supposed* to inject the mouse with poison, then saying that he did just that isn& #39;t a way of blaming him for doing so. By contrast, since the mouse wasn& #39;t supposed to die, the rule-breaker gets the blame there.

That& #39;s it! There& #39;s more to causation than we say with "cause", and when we take this wider view we find that causal thinking isn& #39;t affected by norms *in general*, but only when it seems to be a way of assigning blame. Details, and more evidence, here: https://philpapers.org/rec/SCHCQA-2 ">https://philpapers.org/rec/SCHCQ...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter