This week I was asked to give a presentation about some lessons we might be able to learn from Switzerland& #39;s crisis management in this pandemic. It was a welcome opportunity to take a step back and reflect on that.

- a thread https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🧵" title="Thread" aria-label="Emoji: Thread">

- a thread

Going into this, one could have thought that Switzerland should be able to nail this. And yet - judging by almost any metric - we didn& #39;t/aren& #39;t.

Why could one have thought, prima facie, that we should totally own this?

You could make a long list but just to mention a few rather favorable facts: CH is rich af, enjoys highest trust in government (out of all OECD countries), has the highest total expenditure on health p.c.

You could make a long list but just to mention a few rather favorable facts: CH is rich af, enjoys highest trust in government (out of all OECD countries), has the highest total expenditure on health p.c.

So why did Switzerland fail so badly? That& #39;s the question I tried to give some (tentative) answers to.

But first, a few important caveats (1/3)

- The arguments that follow are condensed (because Twitter), there& #39;s lots more nuance to this than can be fit into a tweet.

- Things are complicated. Really. Reality has a surprising amount of detail, as someone once said.

- The arguments that follow are condensed (because Twitter), there& #39;s lots more nuance to this than can be fit into a tweet.

- Things are complicated. Really. Reality has a surprising amount of detail, as someone once said.

But first, a few important caveats (2/3)

- It& #39;s easy to criticize when you& #39;re not in the hot seat.

Anyone in a position of responsibility who has stuck their neck out and took courageous decisions deserves our respect, even if I might disagree with them.

- It& #39;s easy to criticize when you& #39;re not in the hot seat.

Anyone in a position of responsibility who has stuck their neck out and took courageous decisions deserves our respect, even if I might disagree with them.

But first, a few important caveats (3/3)

- “The owl of Minerva takes its flight only when the shades of night are gathering” - a pretentious way of saying that we might not truly know for a while who was right, who wasn& #39;t, what worked, what didn& #39;t. So some humility is in order.

- “The owl of Minerva takes its flight only when the shades of night are gathering” - a pretentious way of saying that we might not truly know for a while who was right, who wasn& #39;t, what worked, what didn& #39;t. So some humility is in order.

My own pandemic story begins in Rome. I spent all of February 2020 there, as part of an extended holiday between jobs.

Thing started to go a bit crazy in the north of Italy and towards the end of the month I decided that it was time to bail and go back to Switzerland.

Thing started to go a bit crazy in the north of Italy and towards the end of the month I decided that it was time to bail and go back to Switzerland.

Returning was like entering some alternate reality. In Rome everyone was already suitably alarmed and gently freaking out. In Zurich, zero fcks were given.

(Fun fact: Zurich is geographically *closer* to Bergamo than Rome is and Northern Italy is highly integrated with https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🇨🇭" title="Flagge der Schweiz" aria-label="Emoji: Flagge der Schweiz">)

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🇨🇭" title="Flagge der Schweiz" aria-label="Emoji: Flagge der Schweiz">)

(Fun fact: Zurich is geographically *closer* to Bergamo than Rome is and Northern Italy is highly integrated with

And so we waited and waited for what felt like an eternity, until on March 16th 2020 the Federal Council declared an ‘extraordinary situation’ and introduced stringent measures.

Since then, the country& #39;s response has been patchy at best and horrifically ineffective at worst.

Let& #39;s explore some possible reasons why that& #39;s the case.

Let& #39;s explore some possible reasons why that& #39;s the case.

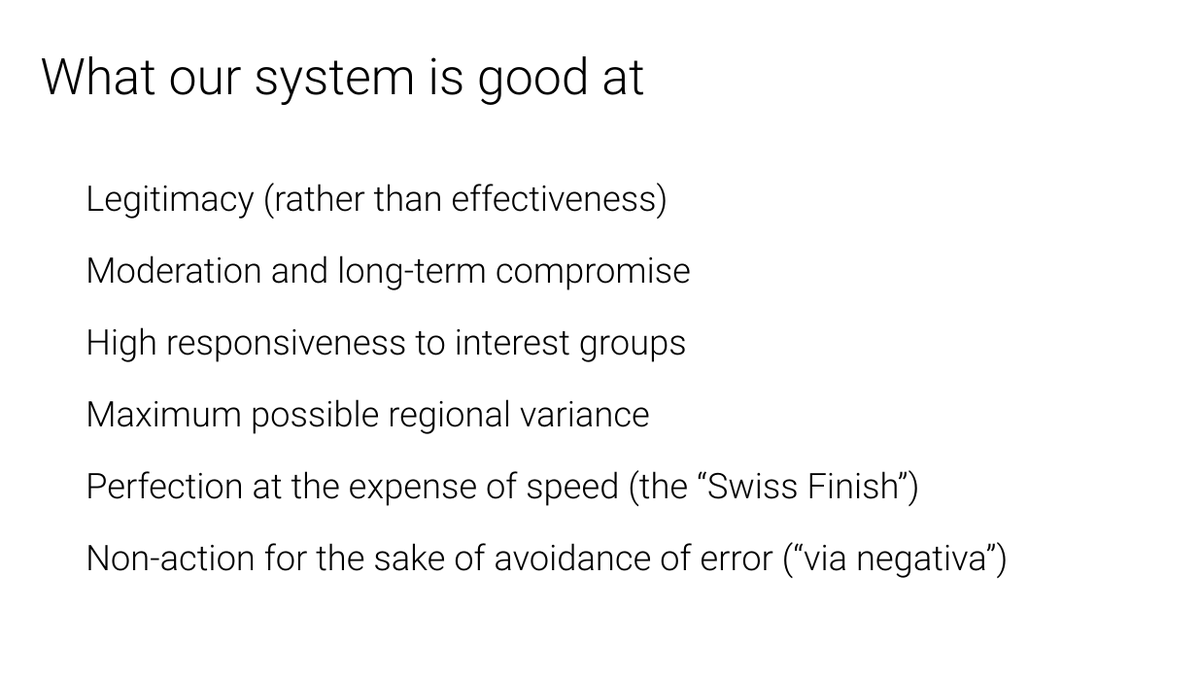

Here& #39;s what the Swiss political system is good at: (1/1)

1) Producing legitimacy

This is a massive asset. The & #39;crisis of legitimacy& #39; which many other countries experience, isn& #39;t a thing (or at least not in the same way).

1) Producing legitimacy

This is a massive asset. The & #39;crisis of legitimacy& #39; which many other countries experience, isn& #39;t a thing (or at least not in the same way).

Here& #39;s what the Swiss political system is good at: (1/2)

2) Moderating the extremes and forging long-term compromise - this is also generally A Good Thing.

2) Moderating the extremes and forging long-term compromise - this is also generally A Good Thing.

Here& #39;s what the Swiss political system is good at: (1/3)

3) Being responsive to every conceivable interest group

You want to defend the interests of horned cows? Go right ahead, the Swiss political system has a way for you to submit your proposed legislation to a popular vote.

3) Being responsive to every conceivable interest group

You want to defend the interests of horned cows? Go right ahead, the Swiss political system has a way for you to submit your proposed legislation to a popular vote.

Here& #39;s what the Swiss political system is good at: (1/4)

4) Allowing maximum possible regional variance

We have 26 cantons, best understood as autonomous regions with vast decision-making powers. Their governments are, and this is important, directly elected.

4) Allowing maximum possible regional variance

We have 26 cantons, best understood as autonomous regions with vast decision-making powers. Their governments are, and this is important, directly elected.

This means that regional variance is politically legitimated and isn& #39;t understood as a "postcode lottery" (compare and contrast that with the UK, for example).

Here& #39;s what the Swiss political system is good at: (1/5)

5) Achieving perfection (albeit at the expense of speed)

The so called "Swiss finish" refers to the obsessive nature with which The Perfect Solution is crafted, and usually no expense (in time or money) is spared.

5) Achieving perfection (albeit at the expense of speed)

The so called "Swiss finish" refers to the obsessive nature with which The Perfect Solution is crafted, and usually no expense (in time or money) is spared.

Here& #39;s what the Swiss political system is good at: (1/6)

6) Non-action for the sake of avoidance of error

This is a serious point and, I believe, generally underestimated. Implicitly the Swiss system follows a logic of "first, do no harm".

6) Non-action for the sake of avoidance of error

This is a serious point and, I believe, generally underestimated. Implicitly the Swiss system follows a logic of "first, do no harm".

Governments are perfectly capable of doing horrific damage, even with the best of intentions.

So maybe saying "hang on, first, let& #39;s make sure we don& #39;t make a mistake" isn& #39;t that dumb.

So maybe saying "hang on, first, let& #39;s make sure we don& #39;t make a mistake" isn& #39;t that dumb.

The classic book on this is btw James C. Scott& #39;s "Seeing Like a State - How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed".

Or take King and Crewe& #39;s (highly entertaining) "The Blunders of our Governments" which chronicles the phenomenally stupid blunders of various UK governments.

No such books have, so far and to the very best of my knowledge, been written about Switzerland& #39;s government. Why?

Because the Swiss system is exceptionally good at avoiding errors of commission.

(Errors of omission are, however, a different thing. We& #39;ll get to that...)

Because the Swiss system is exceptionally good at avoiding errors of commission.

(Errors of omission are, however, a different thing. We& #39;ll get to that...)

In a fast-moving pandemic, the same mechanisms that produce all those lovely attributes listed above really don& #39;t work.

Why does it not work? Mike Ryan, head of the Health Emergencies Programme at WHO, put it this way back in March 2020:

(Here& #39;s a longer version of the clip with a bit more context) https://twitter.com/SkyNews/status/1238504143104421888">https://twitter.com/SkyNews/s...

"If you need to be right before you move, you will never win. Perfection is the enemy of the good (...) Speed trumps perfection. (...) Everyone is afraid of the consequence of error. But the greatest error is not to move".

Now, it would be a bit too easy to say "there you have it, Switzerland doesn& #39;t do speed and imperfection, that& #39;s why we& #39;re doomed" and call it a day.

That& #39;s why I want to examine four facets of this failure which I think are interesting.

That& #39;s why I want to examine four facets of this failure which I think are interesting.

Understanding the finer details of why things fail is important because you can& #39;t “best practices” from elsewhere in the world if they don’t fit the context. Why?

Because (loosely paraphrasing Tolstoy): All the successful countries are alike, but every unsuccessful country is unsuccessful in its own way.

And if we want to know what might be done in Switzerland, we need to understand the specific ways in which Switzerland is unsuccessful.

And if we want to know what might be done in Switzerland, we need to understand the specific ways in which Switzerland is unsuccessful.

Here& #39;s the first of the four facets of failure.

1) Usually the relationship between the federal level and the cantons is & #39;loosely coupled& #39;.

Information and decisions flow both ways, but it& #39;s not a rigid system.

1) Usually the relationship between the federal level and the cantons is & #39;loosely coupled& #39;.

Information and decisions flow both ways, but it& #39;s not a rigid system.

Usually that& #39;s a good thing. & #39;Tightly coupled& #39; complex systems are much more prone to catastrophic failure, & #39;loosely coupled& #39; ones are more forgiving.

The problem, however, is that now we& #39;re arguably in desperate need of some properly tight coupling.

The problem, however, is that now we& #39;re arguably in desperate need of some properly tight coupling.

Vaccine deliveries need to (literally) be moved at the right time to the right place, decisions about restrictions need to be coordinated, and all of this needs to be done at pace.

And the system seems to struggle heavily with achieving that tight coupling.

And the system seems to struggle heavily with achieving that tight coupling.

2) The second facet is what you could call the dirty secret of the so called "laboratory of ideas".

It& #39;s often said that the decentralized nature of decisionmaking between cantons allows for lots of experimentation and then cantons can swiftly learn what works from each other.

It& #39;s often said that the decentralized nature of decisionmaking between cantons allows for lots of experimentation and then cantons can swiftly learn what works from each other.

What& #39;s not to like? In theory, it all sounds great. In actual fact, there seems to be (some, limited) experimentation, but next to no learning.

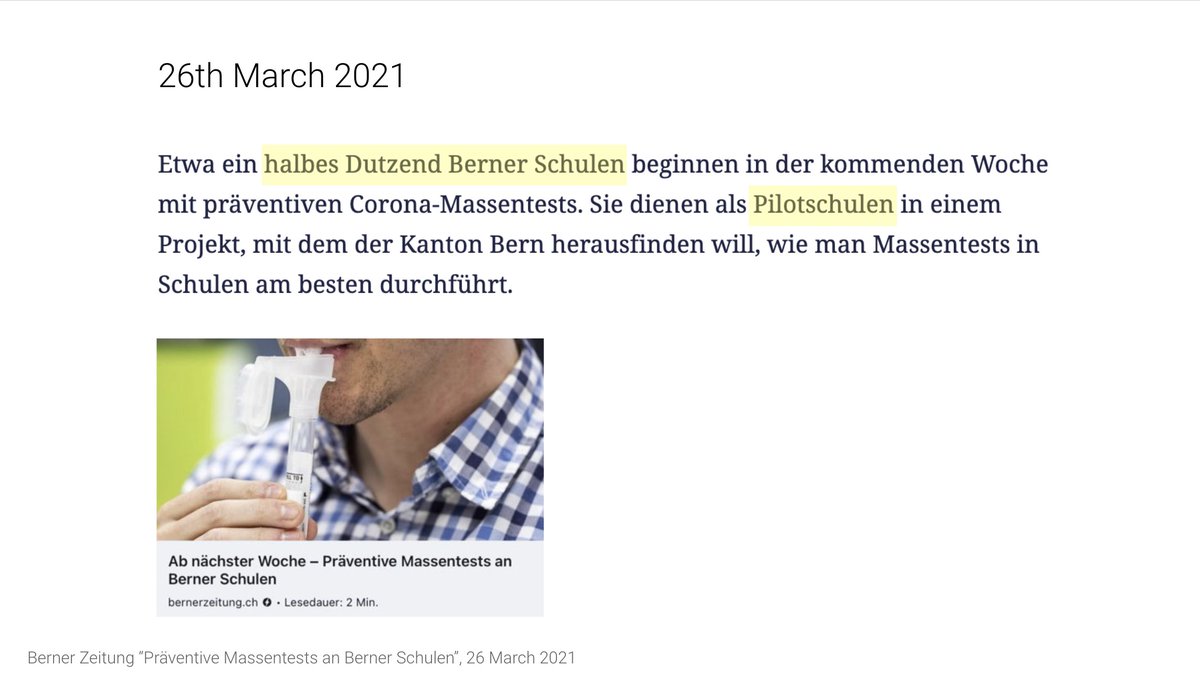

At the end of March the Canton of Bern decided to start a mass testing pilot with six schools. Why?

Well, it makes sense to test the mechanics of this before you roll it out, doesn& #39;t it?

Yes, except that the Canton of Grisons has been running these mass tests *for months*.

Well, it makes sense to test the mechanics of this before you roll it out, doesn& #39;t it?

Yes, except that the Canton of Grisons has been running these mass tests *for months*.

This is one specific example and I& #39;m not familiar with the finer details of the school testing regime in Berne, so maybe I& #39;m missing some important detail here.

But the wider point stands: no one currently gets the impression that cantonal governments are exceptionally quick to learn from others.

3) The third facet of failure relates to compromise - both a Holy Grail in Swiss politics and at the same time a fundamentally broken heuristic.

The Swiss system is, as mentioned above, truly exceptionally good at forging compromise. There& #39;s a generally useful and accepted heuristic which says that - everything else being equal - aiming for compromise is probably a good thing.

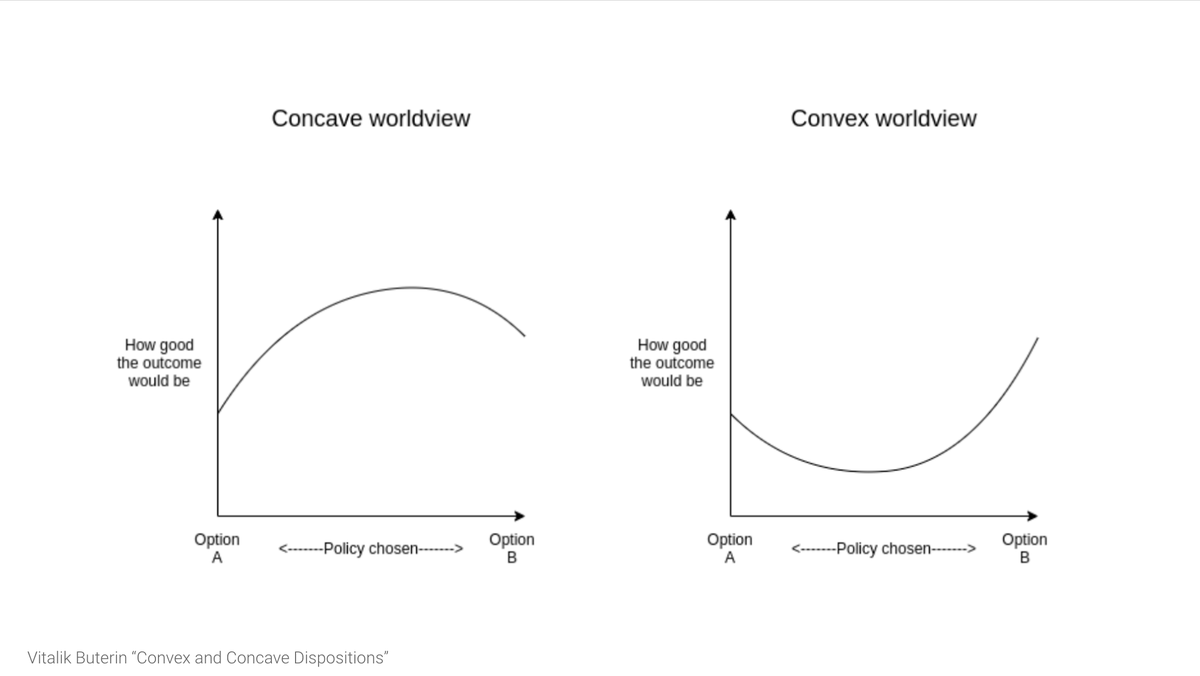

This heuristic holds in & #39;concave& #39; situations. Compromising between Option A (on the left) and Option B (on the right) will in fact lead to a superior outcome, relative to being on either end of the axis.

It, however, does not hold in convex situations.

It, however, does not hold in convex situations.

(The graph above is from @VitalikButerin& #39;s blogpost on "Convex and Concave Dispositions": https://vitalik.ca/general/2020/11/08/concave.html)">https://vitalik.ca/general/2...

In a convex situation compromise leads to an inferior outcome.

The properties of a fast-moving, exponentially growing pandemic are such, that we are in a convex situation.

The properties of a fast-moving, exponentially growing pandemic are such, that we are in a convex situation.

An example: An effective lockdown that pushes R to zero leads to an exponential decline of infections and therefore to quick eradication.

A half-hearted lockdown that only gets R to just below 1 will get you months of pain with not much to show for.

A half-hearted lockdown that only gets R to just below 1 will get you months of pain with not much to show for.

4) Finally, the fourth facet of failure is what might uncharitably be called & #39;self-delusions of competence& #39; in public administration.

We have dramatically underinvested in the digital transformation of our public admin. Before the pandemic too few believed this to be the case.

We have dramatically underinvested in the digital transformation of our public admin. Before the pandemic too few believed this to be the case.

Many efforts have begun, and they& #39;re mostly led by excellent, committed, inspiring, and competent people.

But we have only begun to grasp the sheer scale of the problem. And these people need vastly more resources (mostly: people & power) than they are currently being given.

But we have only begun to grasp the sheer scale of the problem. And these people need vastly more resources (mostly: people & power) than they are currently being given.

Here& #39;s a highly scientific depiction of the problem:

These four facets of failure explain, I& #39;d argue, at least in part why the Swiss political system hasn& #39;t covered itself in glory in the fight against this pandemic.

These facets are, of course, somewhat arbitrary. There are other aspects which are probably just as important.

But ultimately all of these explanations fail to capture some larger truth about what is happening.

But ultimately all of these explanations fail to capture some larger truth about what is happening.

Ultimately this feels like a crisis of ambition and of imagination.

It feels like we& #39;ve just given up. It& #39;s this defeatist position which I find deeply unsettling and sad.

It feels like we& #39;ve just given up. It& #39;s this defeatist position which I find deeply unsettling and sad.

This should have been a moment for us to shine, to deploy the vast resources this place has, in order to overcome a monumental challenge.

(And, to be clear, much of that happened. Just not nearly enough)

(And, to be clear, much of that happened. Just not nearly enough)

The biggest hurdle seems to be some sort of & #39;business as usual& #39; mindset.

The countries/places that did comparatively well all shifted into a & #39;all-out effort& #39; mode. We didn& #39;t.

The countries/places that did comparatively well all shifted into a & #39;all-out effort& #39; mode. We didn& #39;t.

Just before Easter 2021 an official from the Canton of Basel-Stadt said that the vaccination center would remain closed over the long weekend because a vaccine shipment had arrived just before and asking people to show up at short notice "wouldn& #39;t go down well".

I don& #39;t want to dunk on this one particular official, I& #39;m trying to make a broader point: this attitude/posture seems emblematic of what I& #39;ve tried to express above and what& #39;s wrong with how we& #39;re handling this.

Why we weren& #39;t able to shift into an & #39;all-out effort& #39; mode is a question for a different thread. But I do think that ultimately this question is the crux of the matter.

Here& #39;s the blog post version of this thread: https://dannybuerkli.medium.com/some-lessons-we-might-be-able-to-learn-from-switzerlands-crisis-management-in-this-pandemic-b72deb43c6e5?source=friends_link&sk=44849700101205561fb045819ff7338f">https://dannybuerkli.medium.com/some-less...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter