Short Thread — on Developmental Pessimism.

Essentially a reaction to an article in Dissent called ‘End of Development’. More precisely it’s about the end of development as industrialisation. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-end-of-development">https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/t...

Essentially a reaction to an article in Dissent called ‘End of Development’. More precisely it’s about the end of development as industrialisation. https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/the-end-of-development">https://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/t...

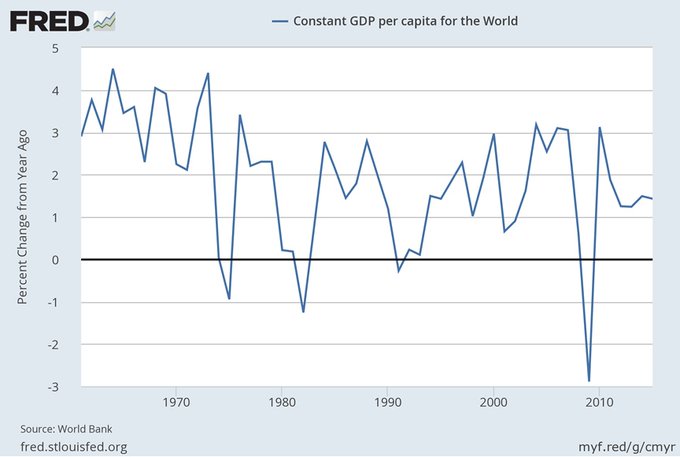

Its basic argument is that the growth slowdown is not confined to the rich countries; it’s actually global, thanks to premature deindustrialisation in the Global South. The (rhetorical) virtue of the article is that it looks at the growth slowdown as a global, unified story.

First, the article requires one major correction. The starting point for the article is that there has been a slowdown in global growth. But Barker uses growth rates of aggregate world GDP, which obviously includes population growth; rather than world GDP per capita.

The slowdown in world GDP per capita growth isn& #39;t as bad as the article says.

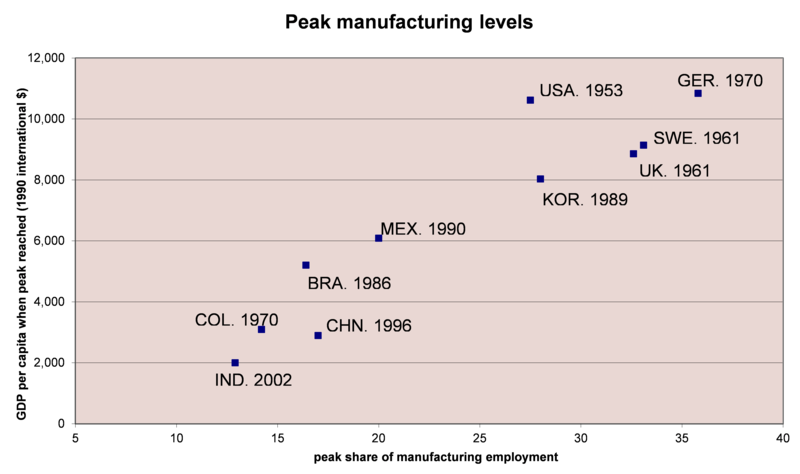

Also the article also overstates peak manufacturing employment shares in several countries. Germany, Japan & the UK never employed 40-50% of its labour force in manufacturing, nor Brazil 23%. Actual figures:

Initially I had a very negative reaction. I was distracted (triggered, really) by his references to the term & #39;secular stagnation& #39; & Brenner& #39;s Economics of Global Turbulence. Barker talks a lot abt global demand deficiency as well as global excess capacity. That made my eyes roll

Also, in the rich countries, there is a debate within the left about (for lack of a better term) "Keynesian nostalgia", whether it& #39;s possible to recreate "the Capitalism We Had in the ’50s and ’60s, Only Without the Misogyny and the Racism" (title of a book Barker gently derides)

( I& #39;d always thought that & #39;nostalgia& #39; was about reviving or strengthening (depending on country) the post-war social democratic welfare state & unionism, NOT the historically high growth rates of the Trente Glorieuses. )

( But I suppose some people must believe postwar institutions caused the high growth rates, whereas I find that unlikely. More likely that high growth rates helped sustain capital-labour cooperation & faciliated the social democratic order. )

Barker seems to side with the anti-nostalgics. That postwar period was historically exceptional and you can& #39;t bring it back.

I think that take is basically right, but I still think the discussion of the causes of the growth slowdown in developing countries, is subpar.

I think that take is basically right, but I still think the discussion of the causes of the growth slowdown in developing countries, is subpar.

First, in the rich countries, the high growth rates were historically unique for both techological demographic reasons. You know the by-now-oft-told Gordon story about the rash of nonrepeatable inventions slowly adopted around midcentury.

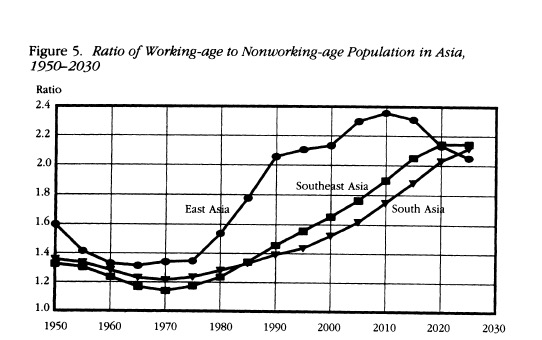

There is also the demographic story: the Trente Glorieuses coincided with a very low dependency ratio.

Also see here https://twitter.com/pseudoerasmus/status/1298229503882297344">https://twitter.com/pseudoera...

The role of demographics in the so-called East Asia Miracle is also generally underestimated. (I& #39;m not saying there was no & #39;miracle& #39; in East Asia; just that some of its very high growth rates received a boost from demographics)

Many people don’t realise that many rich countries were still very agricultural in 1945-50. So reducing the agricultural share alone was a major contributor to post-war growth.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter