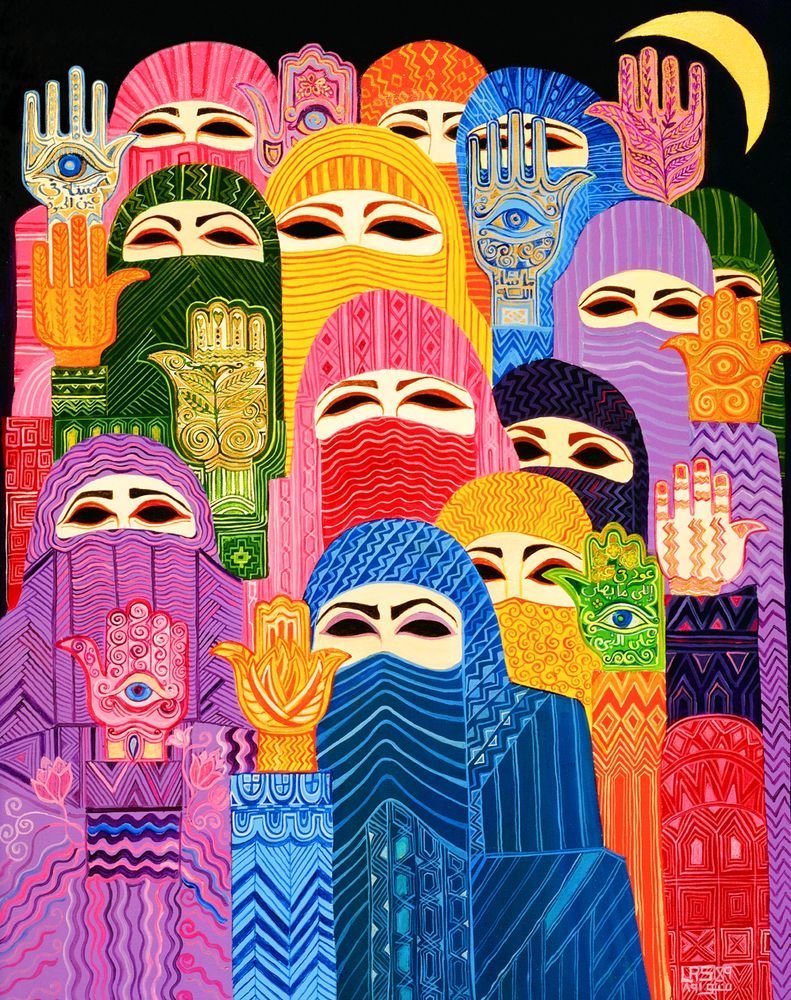

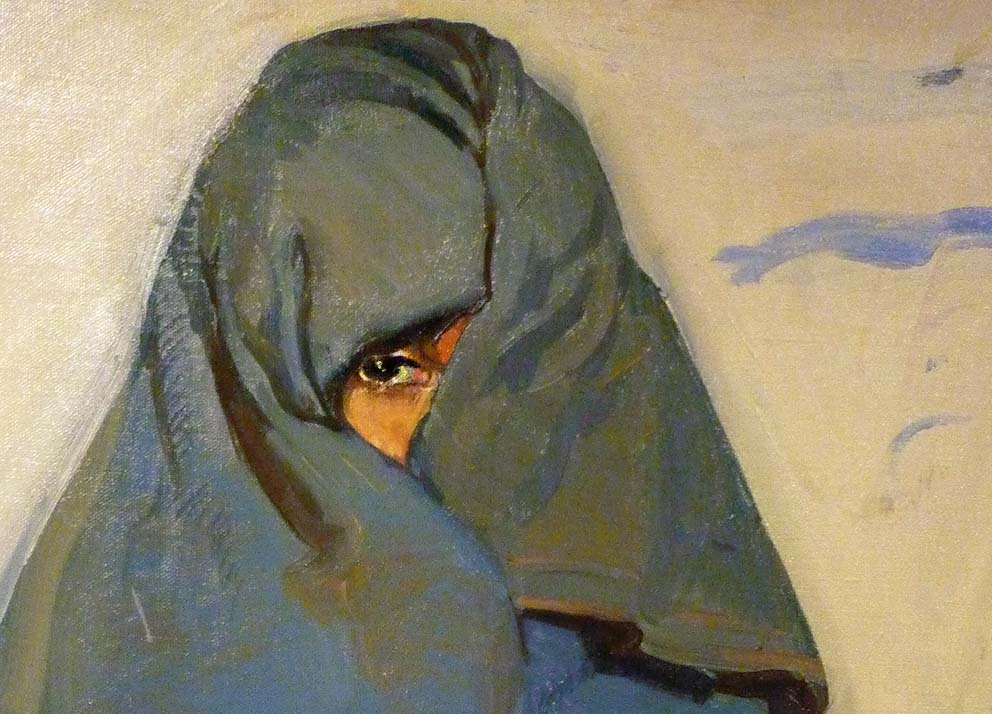

The fifth Hafsa bint Sirin thread. Despite taking part in legal debates as a social and intellectual elite and a well-known Qur’an reciter in her day, she comes to be known in later sources for being a pious recluse. Grrr. So how and why? Artist Habiba El-Sayed, "Shared Pain."

As I mentioned in the last thread, the idealization of women’s pious withdrawal in the world extends to secluding women from public exposure in the texts themselves, which is exactly why they are at the centre of my novels, The Sufi Mystery Quartet. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1378004836629745667?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

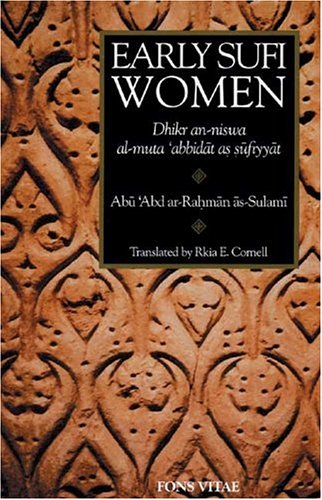

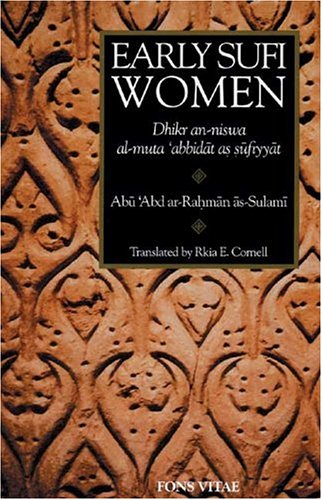

Sufi and pious women were mentioned in very early sources, then dropped almost in their entirety, reappearing in the 5th century in only in two biographical sources in significant numbers: Sulami’s Early Sufi Women (Dhikr) and Ibn al-Jawzi’s Characteristics of the Pure (Sifat).

As is the case with all biographical literature, their accounts reveal the editorial impulses of their compilers. Both Sulami and Ibn al-Jawzi emphasize pious withdrawal from social engagement in many of the narratives. Hafsa bint Sirin is a great example to see how it& #39;s done.

Ash Geissinger’s chapter in Reda and Amin’s Islamic Interpretation Tradition and Gender Justice examines the editorial work sidelining women’s religious authority as interpreters of the Qur’an, including a close reading of Sulami and Ibn al-Jawzi’s treatment of Hafsa bint Sirin.

There& #39;s a lot going on in that chapter. I’m only going pick up one thread in support of my own observations that Sulami and Ibn al-Jawzi idealize Hafsa as modest and secluded, rather than socially engaged and scholarly. Click here to give it a full read. https://bit.ly/3uLBEgp ">https://bit.ly/3uLBEgp&q...

Because other accounts of Hafsa’s life and work are available in a number of sources--coming soon--it won& #39;t be too hard to see later how S & IJ’s accounts of Hafsa end up erasing or backgrounding her engaged scholarly and social life. So just stay with me.

Sulami’s entry on Hafsa is one of the most austere treatments in his collection of mystic women. He mentions that Hafsa was a renunciant, scrupulous, and known for “signs” and “miracles.” Then, he relates only one story about her:

"Hafsa bint Sirin used to light her lamp at night, and then would rise to worship in her prayer area. At times, the lamp would go out, but it would continue to illuminate her house until daylight."

He does not mention her highly respected knowledge of Qur’an and Hadith, her ability to reason legally from these sources, nor that male students came to study with her.

Why? In her introduction to Early Sufi Women, Cornell argues that Sulami is primarily interested in calling attention to women’s spiritual vocation in these reports, portraying them as “career women of the spirit,” so he does not mention their social or scholarly lives.

But I have to ask why honouring women’s spiritual vocation requires removing them from their scholarly and social contexts such that, for example in Hafsa’s case, there is no trace of a woman left, just a pure soul that kindles lamps?

I offered an answer in an earlier thread. As women’s participation in public religious life became a problem for some men, they were dropped from the sources or in some cases, their depictions were “veiled” to vouchsafe their authority. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1368609130324328448?s=2">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

Sulami is not the bad guy. Sufis were under outside pressure to reject women’s authority in their communities and Sulami’s spare treatment of Hafsa is likely a reflection of those concerns. Abdel Latif and @alakhira Nguyen discuss these wider pressures. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1368609192119042054?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

Ibn al-Jawzi has a fuller treatment that allows Hafsa some bodily humanity and cites her intellectual and pious achievements. But the narrative flow of the accounts portrays Hafsa as a learned woman whose interpretive choices and piety kept her at a remove from others.

He opens his entry on Hafsa with several accounts that act as the lens through which one reads the others. She may have taught men out of her home, but the takeaway is that she is a woman of modesty who desired seclusion most of all. Artist: Ortiz Echague, cut of "Two Women..."

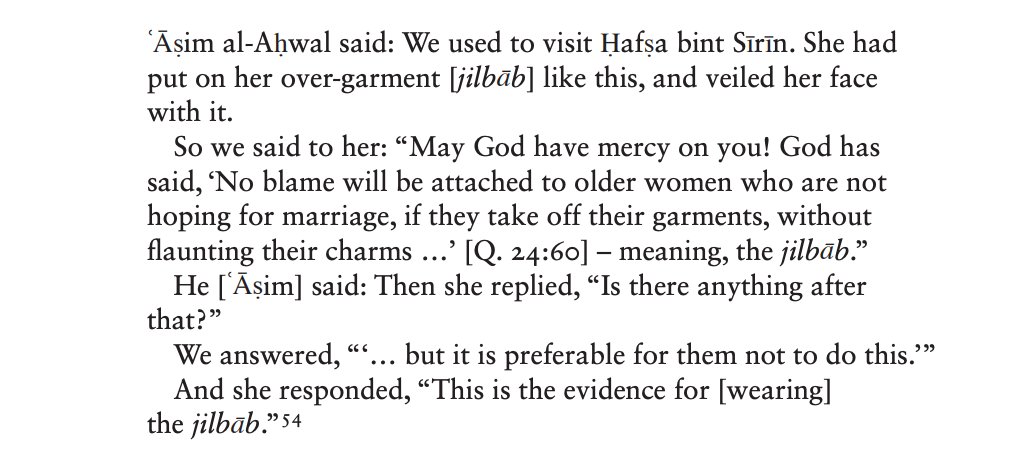

The following anecdote pays tribute to her as a scholar of the Qur’an and its legal interpretation. Her male students query her on her interpretation of a verse and she corrects them in no uncertain terms. Looks good, right?

As Geissinger writes, her male students challenge her as if they have the right to tell her how to dress and how to interpret the verse. There& #39;s something going on here. As these stories work in these sources overall, it actually centres them, not her, and their higher status.

So while the story vouchsafes her reliability--she is above moral reproach and has a keen mind--it relies on depicting her as low social status. Men got public scholarly authority through humility, not women. And *she* saw herself as elite. More next week. https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1376180265043787778?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

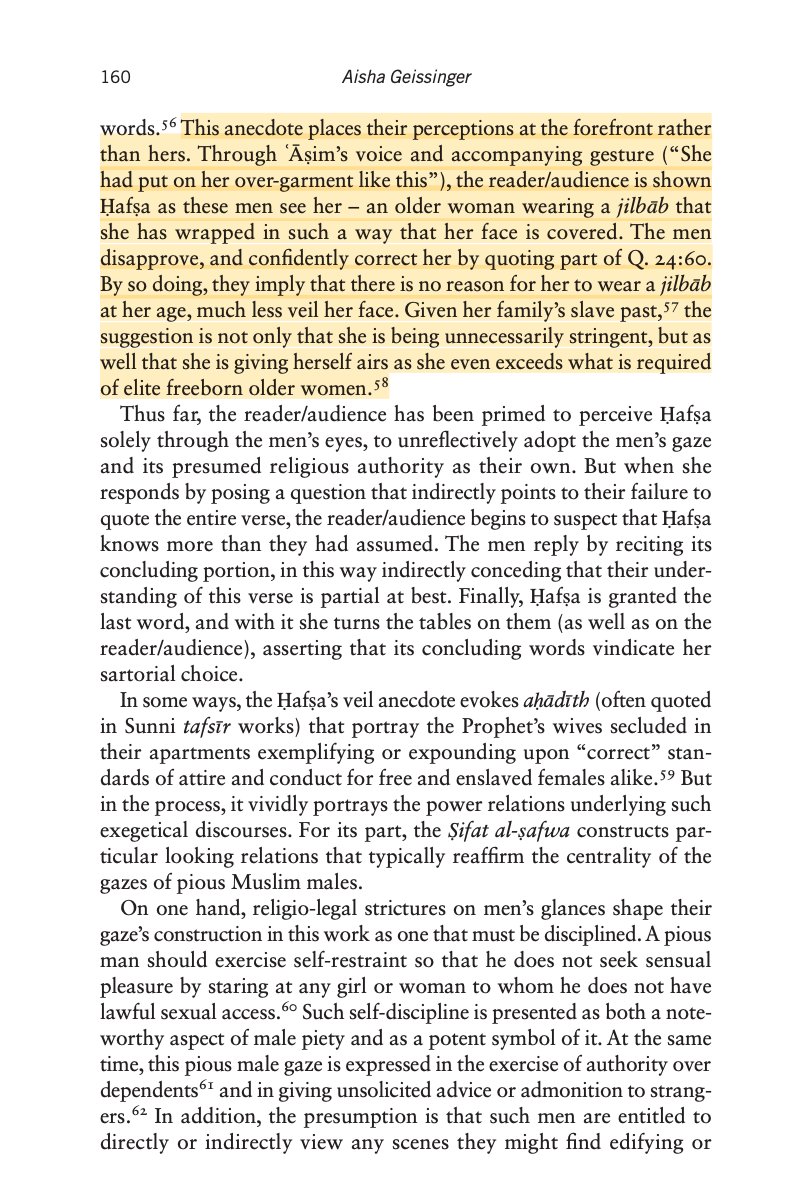

The two other accounts expand on this theme, establishing her as a woman of great piety and a committed recluse. You might say, “So she was a recluse? So what?” But when we look at the social clues and history in other sources in later threads, it will be clear. And you’ll be  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">

In other accounts she is likewise scholarly, but mainly standing at length in prayer, fasting, patiently bearing up under the grief over the death of her beloved son, and most of all secluding herself from others. But are we reading too much into it?

Geissinger told me after looking at all the men’s and women’s entries in the Sifat that IJ portrays women in ways that reinforce stereotypes of them as less knowledgeable and their piety as more experiential, domestic, and solitary. Artist: Habiba El-Sayed "Weight of an Apology"

Again, why? I don’t know what his circumstances were (can someone who knows help out here?). But he was among those who pressured Sufi communities by criticizing their lack of conformity to his social and theological norms. He was kind of intense about it.

But enough of the negative stuff! In the threads that follow, I’ll stop talking about how men frame her life and do some framing of my own. I’ll upend these depictions to the point that you’ll ask when was this scholarly recluse ever alone! Artist: Laila Shawa, "Hands of Fatima"

If this interests you, maybe you& #39;ll like my Sufi Mysteries Quartet. I use the historical research on this period to explore these questions and write women at the centre of the narrative. See my master thread for the books and past threads on woman saints! https://twitter.com/waraqamusa/status/1378004836629745667?s=20">https://twitter.com/waraqamus...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

" title="The two other accounts expand on this theme, establishing her as a woman of great piety and a committed recluse. You might say, “So she was a recluse? So what?” But when we look at the social clues and history in other sources in later threads, it will be clear. And you’ll be https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

" title="The two other accounts expand on this theme, establishing her as a woman of great piety and a committed recluse. You might say, “So she was a recluse? So what?” But when we look at the social clues and history in other sources in later threads, it will be clear. And you’ll be https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👀" title="Augen" aria-label="Emoji: Augen">" class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>