1/

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I& #39;ll walk you through the basics of leverage -- in our personal lives and in the companies we invest in.

Get a cup of coffee.

In this thread, I& #39;ll walk you through the basics of leverage -- in our personal lives and in the companies we invest in.

2/

Imagine we have an idea for a business.

To start the business, we need to put in $1M.

In return, the business will generate $250K for us every year -- for 10 years.

So, our upfront investment is $1M. But over the next 10 years, we get to take out $250K * 10 = $2.5M.

Imagine we have an idea for a business.

To start the business, we need to put in $1M.

In return, the business will generate $250K for us every year -- for 10 years.

So, our upfront investment is $1M. But over the next 10 years, we get to take out $250K * 10 = $2.5M.

3/

This is an "unleveraged" annual return (IRR) of about 21.4%.

"Unleveraged" means we don& #39;t borrow any money.

That is, we use our own money for the initial $1M investment.

For more on IRRs and how to calculate them: https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1284536987861446657">https://twitter.com/10kdiver/...

This is an "unleveraged" annual return (IRR) of about 21.4%.

"Unleveraged" means we don& #39;t borrow any money.

That is, we use our own money for the initial $1M investment.

For more on IRRs and how to calculate them: https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1284536987861446657">https://twitter.com/10kdiver/...

4/

What if we instead borrow part of the $1M?

This would be a "leveraged" scenario.

For example, let& #39;s say we use 4:1 leverage.

That means: to get the initial $1M, we put in $200K of our own money, and borrow the remaining $800K.

$800K : $200K = 4:1.

What if we instead borrow part of the $1M?

This would be a "leveraged" scenario.

For example, let& #39;s say we use 4:1 leverage.

That means: to get the initial $1M, we put in $200K of our own money, and borrow the remaining $800K.

$800K : $200K = 4:1.

5/

Of course, when we borrow money, we have to pay interest.

Suppose our interest rate is 5% per year.

That means: we pay 5% of our $800K loan = $40K in interest each year.

Of course, when we borrow money, we have to pay interest.

Suppose our interest rate is 5% per year.

That means: we pay 5% of our $800K loan = $40K in interest each year.

6/

Plus, at the end of 10 years, we have to return the principal ($800K).

To do this, let& #39;s say we set aside $80K per year -- in each of the next 10 years.

At the end of 10 years, that will leave us with $80K * 10 = exactly the $800K we& #39;ll need to pay back the loan.

Plus, at the end of 10 years, we have to return the principal ($800K).

To do this, let& #39;s say we set aside $80K per year -- in each of the next 10 years.

At the end of 10 years, that will leave us with $80K * 10 = exactly the $800K we& #39;ll need to pay back the loan.

7/

So, of the $250K our business will generate for us each year, $40K goes towards interest and $80K is set aside to pay back the principal.

This leaves us with $250K - ($40K + $80K) = $130K in cash that we can take out of the business each year.

So, of the $250K our business will generate for us each year, $40K goes towards interest and $80K is set aside to pay back the principal.

This leaves us with $250K - ($40K + $80K) = $130K in cash that we can take out of the business each year.

8/

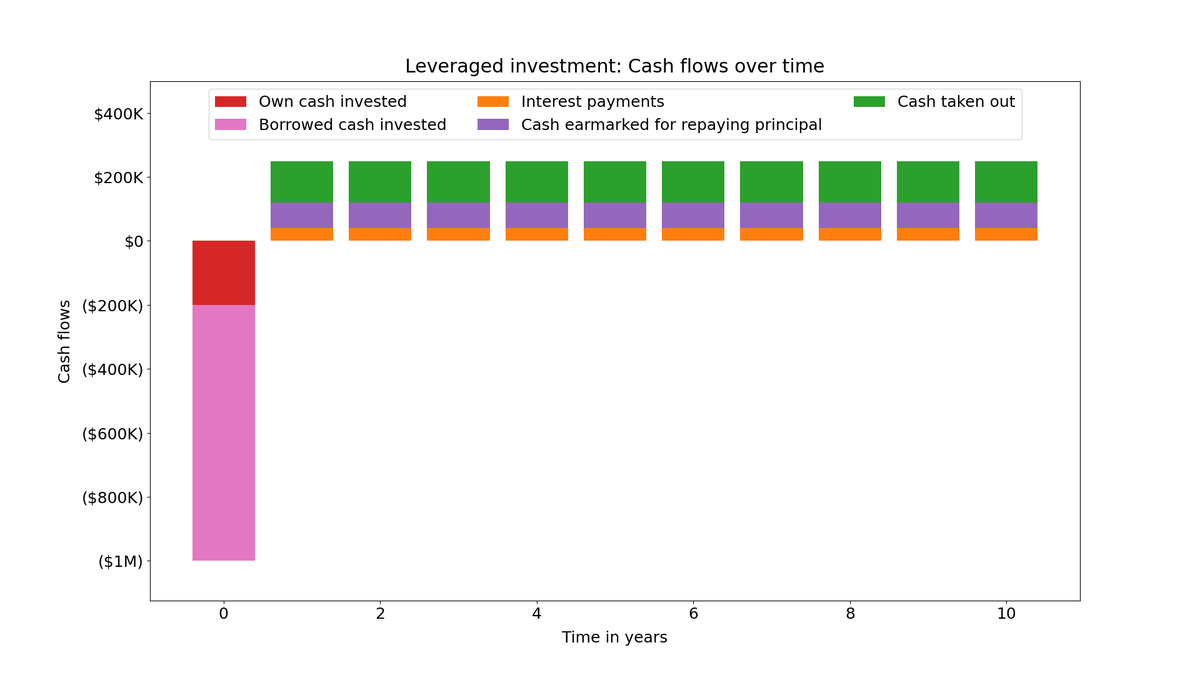

So, *with* leverage, our cash flows look like this:

We put in $200K upfront.

We take out $130K per year -- over the next 10 years.

That& #39;s a *leveraged* IRR of about 64.6% (annualized).

So, *with* leverage, our cash flows look like this:

We put in $200K upfront.

We take out $130K per year -- over the next 10 years.

That& #39;s a *leveraged* IRR of about 64.6% (annualized).

9/

So:

Unleveraged IRR = ~21.4% per year.

Leveraged IRR = ~64.6% per year.

That& #39;s the power of leverage.

In physics, leverage lets us move a heavy object using a small force.

In investing, leverage allows us to get a high return using a small amount of capital.

So:

Unleveraged IRR = ~21.4% per year.

Leveraged IRR = ~64.6% per year.

That& #39;s the power of leverage.

In physics, leverage lets us move a heavy object using a small force.

In investing, leverage allows us to get a high return using a small amount of capital.

10/

But unfortunately, that& #39;s not the whole story.

The problem is: Leverage comes with risk.

This risk decreases our margin of safety.

But unfortunately, that& #39;s not the whole story.

The problem is: Leverage comes with risk.

This risk decreases our margin of safety.

11/

For example, what happens if our business performs below our expectations?

That is, what if our $250K per year projection turns out to be overly optimistic?

How much of a hit can we take to that $250K before we start losing money?

For example, what happens if our business performs below our expectations?

That is, what if our $250K per year projection turns out to be overly optimistic?

How much of a hit can we take to that $250K before we start losing money?

12/

In the *unleveraged* case, we put in $1M of our own money.

So, as long as the business makes at least $100K per year (over 10 years), we won& #39;t lose money. We& #39;ll be "in the black".

That is, our "margin of safety" is $250K - $100K = $150K per year.

In the *unleveraged* case, we put in $1M of our own money.

So, as long as the business makes at least $100K per year (over 10 years), we won& #39;t lose money. We& #39;ll be "in the black".

That is, our "margin of safety" is $250K - $100K = $150K per year.

13/

What about the *leveraged* case?

Here, we need $120K per year just to "service" the loan ($40K for interest, $80K for principal).

Plus, we need an extra $20K per year to break-even on the $200K of our own money that we put in.

What about the *leveraged* case?

Here, we need $120K per year just to "service" the loan ($40K for interest, $80K for principal).

Plus, we need an extra $20K per year to break-even on the $200K of our own money that we put in.

14/

So, for us to be "in the black", the business will need to generate at least $120K + $20K = $140K per year.

That means: our "margin of safety" is only $250K - $140K = $110K per year.

So, leverage has reduced our margin of safety by ~27% -- from $150K to $110K per year.

So, for us to be "in the black", the business will need to generate at least $120K + $20K = $140K per year.

That means: our "margin of safety" is only $250K - $140K = $110K per year.

So, leverage has reduced our margin of safety by ~27% -- from $150K to $110K per year.

15/

This is the crucial thing to understand when it comes to leverage:

Leverage can amplify returns.

But it also amplifies risk.

As leverage increases, our tolerance for error -- our "margin of safety" -- decreases; it doesn& #39;t take much to push us from black to red.

This is the crucial thing to understand when it comes to leverage:

Leverage can amplify returns.

But it also amplifies risk.

As leverage increases, our tolerance for error -- our "margin of safety" -- decreases; it doesn& #39;t take much to push us from black to red.

16/

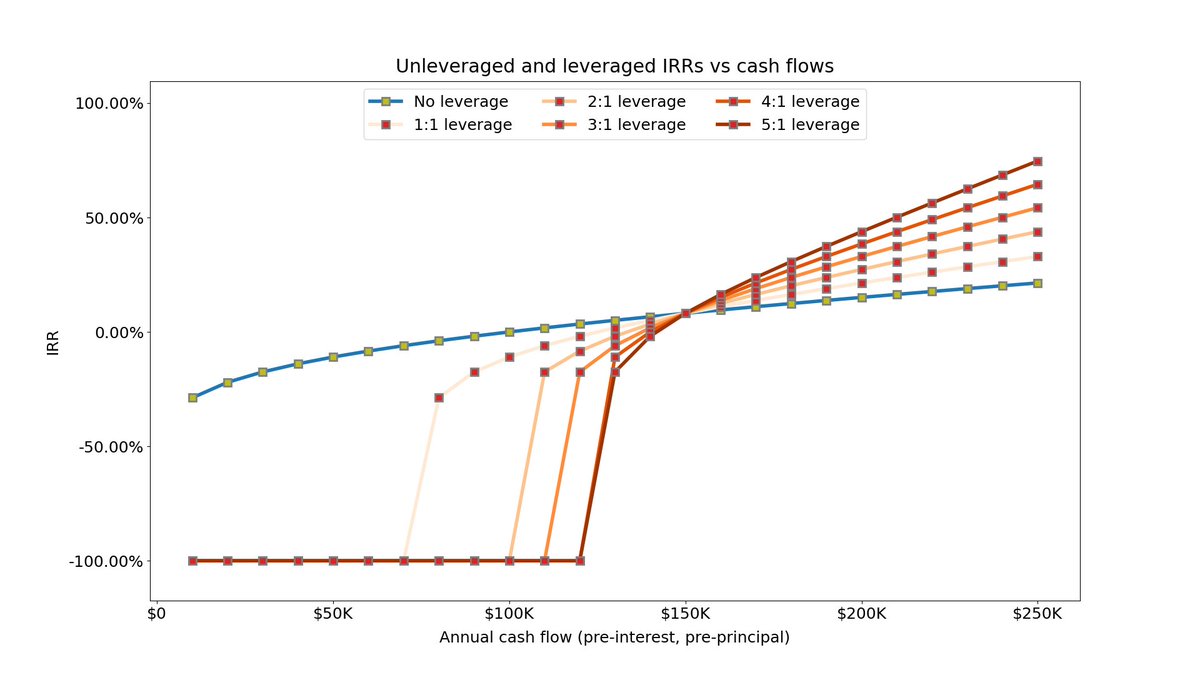

For example, this plot shows our IRR vs our business& #39;s cash flows -- at various leverage levels (1:1, 2:1, etc.).

With no leverage (the blue line), our IRR drops gracefully as cash flows decrease.

But as leverage increases, our IRRs drop off much more sharply.

For example, this plot shows our IRR vs our business& #39;s cash flows -- at various leverage levels (1:1, 2:1, etc.).

With no leverage (the blue line), our IRR drops gracefully as cash flows decrease.

But as leverage increases, our IRRs drop off much more sharply.

17/

Of course, businesses employ various kinds of leverage -- some more dangerous than others.

For example, some businesses use short term liabilities that they constantly "roll over".

This can include negative working capital, insurance float, deferred taxes, etc.

Of course, businesses employ various kinds of leverage -- some more dangerous than others.

For example, some businesses use short term liabilities that they constantly "roll over".

This can include negative working capital, insurance float, deferred taxes, etc.

18/

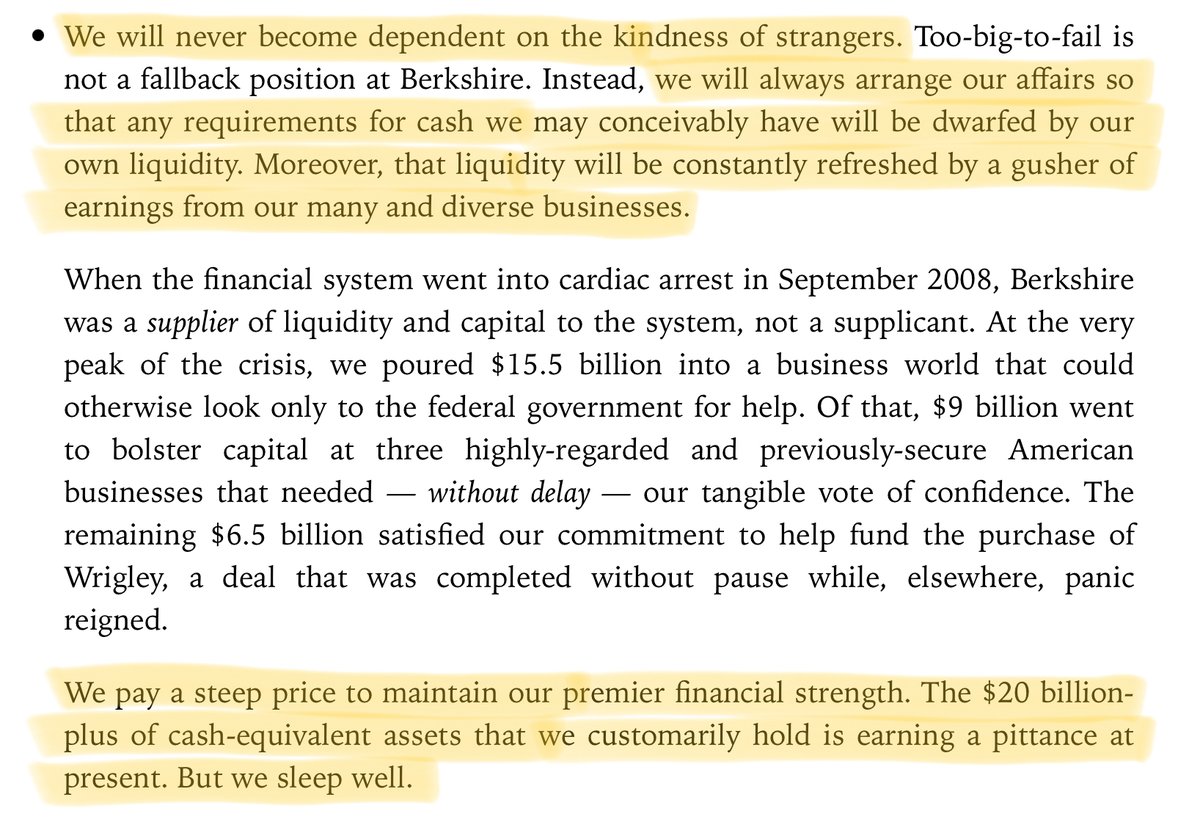

Usually, this leverage is benign.

But for that:

a) the liability shouldn& #39;t suddenly shrink by a lot (eg, insurance policies that run off but don& #39;t renew), and

b) the business shouldn& #39;t rely on credit markets (ie, the kindness of strangers) to roll over short term debt.

Usually, this leverage is benign.

But for that:

a) the liability shouldn& #39;t suddenly shrink by a lot (eg, insurance policies that run off but don& #39;t renew), and

b) the business shouldn& #39;t rely on credit markets (ie, the kindness of strangers) to roll over short term debt.

19/

Long term debt (eg, via corporate bonds) is another form of leverage.

This is somewhat more risky -- as periodic interest and principal payments are usually required.

But as long as such obligations are fixed and known ahead of time, they can be planned for.

Long term debt (eg, via corporate bonds) is another form of leverage.

This is somewhat more risky -- as periodic interest and principal payments are usually required.

But as long as such obligations are fixed and known ahead of time, they can be planned for.

20/

The most dangerous form of leverage is one that could require the business to post a lot of cash at short notice.

For example, a bank run.

Or a naked derivatives contract that blows up.

Or a disaster that triggers claims from a large number of insurance policies.

The most dangerous form of leverage is one that could require the business to post a lot of cash at short notice.

For example, a bank run.

Or a naked derivatives contract that blows up.

Or a disaster that triggers claims from a large number of insurance policies.

22/

When we invest in companies that employ significant amounts of leverage, it& #39;s crucial to understand our margin of safety -- how bad can things become before the result is permanent loss of capital?

When we invest in companies that employ significant amounts of leverage, it& #39;s crucial to understand our margin of safety -- how bad can things become before the result is permanent loss of capital?

23/

Ideally, the business& #39;s cash flows (even in bad years) should more than cover any interest/principal payments.

Also, the business should have sufficient balance sheet strength (ie, assets that can be readily converted to cash) to meet all near-term obligations.

Ideally, the business& #39;s cash flows (even in bad years) should more than cover any interest/principal payments.

Also, the business should have sufficient balance sheet strength (ie, assets that can be readily converted to cash) to meet all near-term obligations.

24/

Similar logic also applies to managing leverage in our *personal* finances.

Here are a few tips for that.

Tip 1. We should never trade on margin. It& #39;s a Russian roulette type situation.

Most of the time, securities bought on margin may not go down drastically.

Similar logic also applies to managing leverage in our *personal* finances.

Here are a few tips for that.

Tip 1. We should never trade on margin. It& #39;s a Russian roulette type situation.

Most of the time, securities bought on margin may not go down drastically.

25/

But from time to time, they will.

This can trigger a "margin call" that can obliterate us.

In effect, this transforms "short term volatility" into "long term risk".

So, it& #39;s best to avoid trading on margin, naked options strategies, etc.

But from time to time, they will.

This can trigger a "margin call" that can obliterate us.

In effect, this transforms "short term volatility" into "long term risk".

So, it& #39;s best to avoid trading on margin, naked options strategies, etc.

26/

Tip 2. As far as possible, we should avoid taking out a loan to buy a *depreciating* asset.

This includes automobiles, and most things bought with credit cards.

So, a corollary is to pay off credit cards in full each month.

Tip 2. As far as possible, we should avoid taking out a loan to buy a *depreciating* asset.

This includes automobiles, and most things bought with credit cards.

So, a corollary is to pay off credit cards in full each month.

27/

Tip 3: When taking out a loan to buy an *appreciating* asset (eg, a mortgage to buy a house), we should follow 3 simple rules.

Rule 1. We should clearly understand our obligations (eg, fixed vs variable interest rates, monthly payments, additional insurance needed, etc.).

Tip 3: When taking out a loan to buy an *appreciating* asset (eg, a mortgage to buy a house), we should follow 3 simple rules.

Rule 1. We should clearly understand our obligations (eg, fixed vs variable interest rates, monthly payments, additional insurance needed, etc.).

28/

Rule 2. Our *current* earning power and assets on hand should be more than adequate to meet our obligations (both interest and principal).

Rule 3. Margin of safety. We should be able to take a reasonable hit to our earnings/assets and still meet our obligations.

Rule 2. Our *current* earning power and assets on hand should be more than adequate to meet our obligations (both interest and principal).

Rule 3. Margin of safety. We should be able to take a reasonable hit to our earnings/assets and still meet our obligations.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter