We have looked carefully at incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children in recent weeks for any impact of the phased return to the classroom. The data, and thorough public health investigation, confirm that schools remain a low-risk environment. 1/16

Schools are low risk because of the mitigation and protection measures put in place by teachers, principals, families, general practitioners and public health doctors. 2/16

The data show a moderate and transient increase in cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection reported in children, not directly because of the return to in-person education, but due to increased detection, or case ascertainment, related to an increase in testing. 3/16

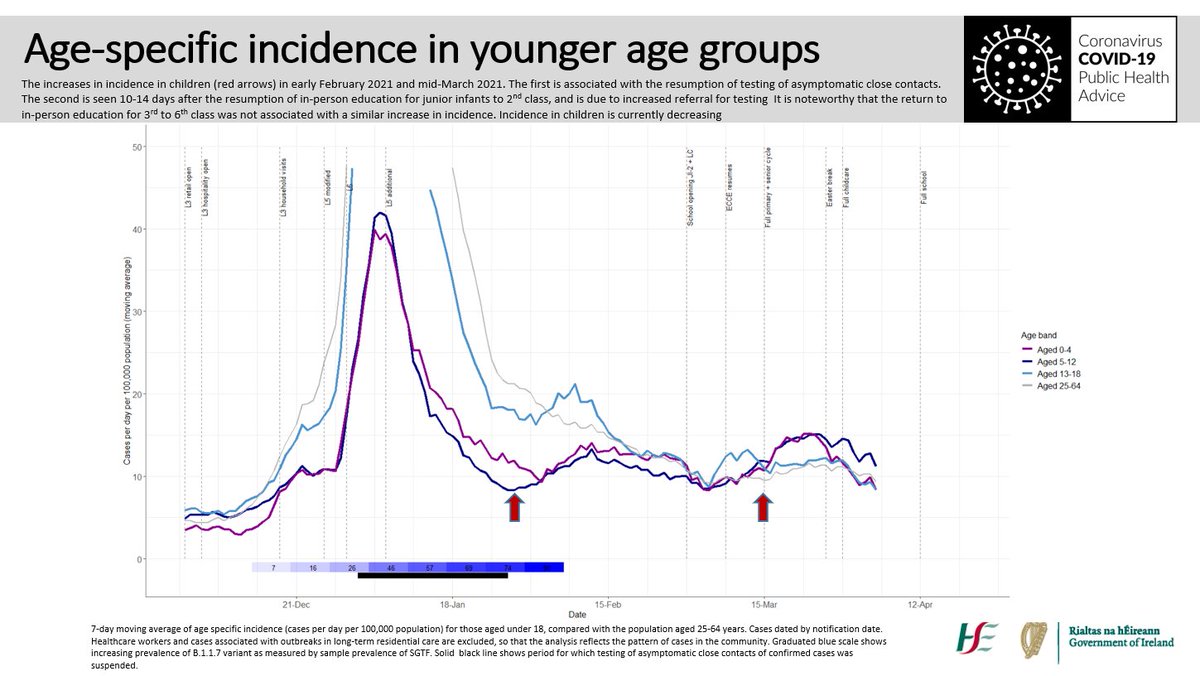

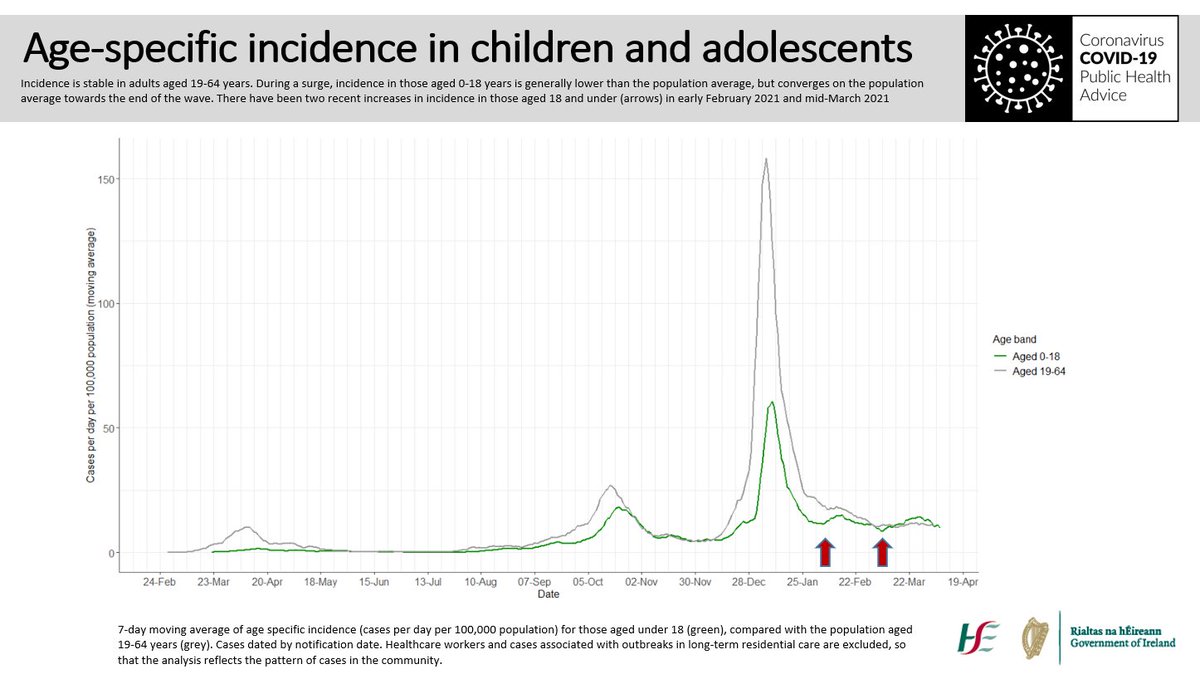

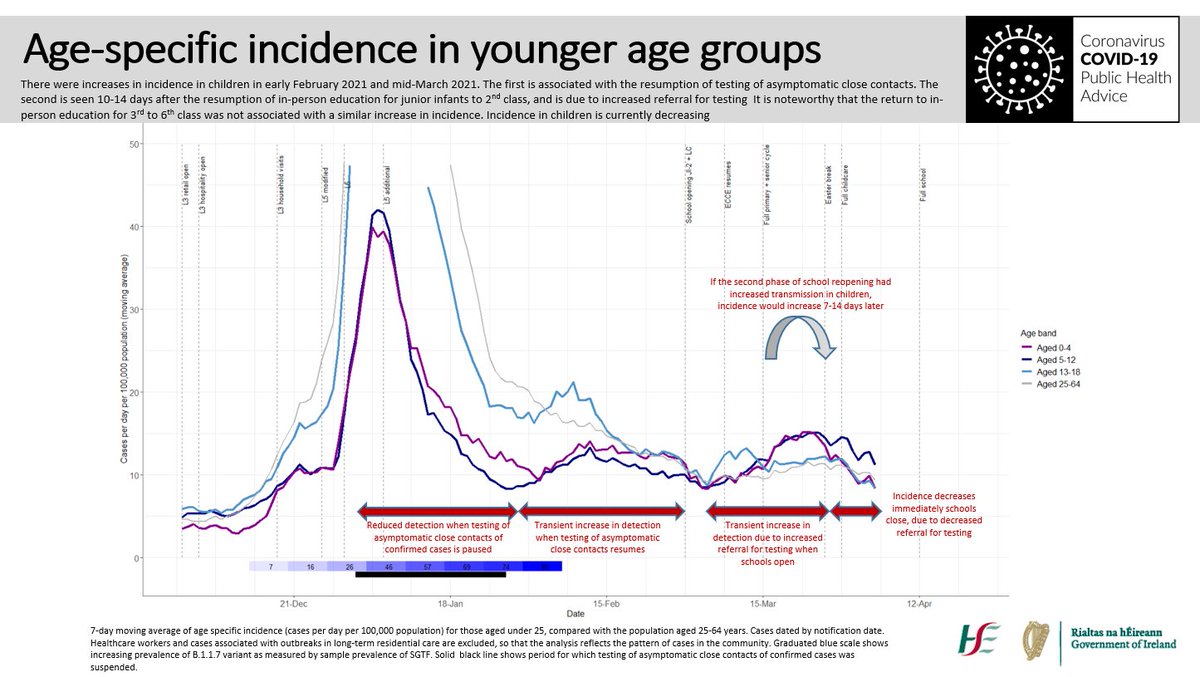

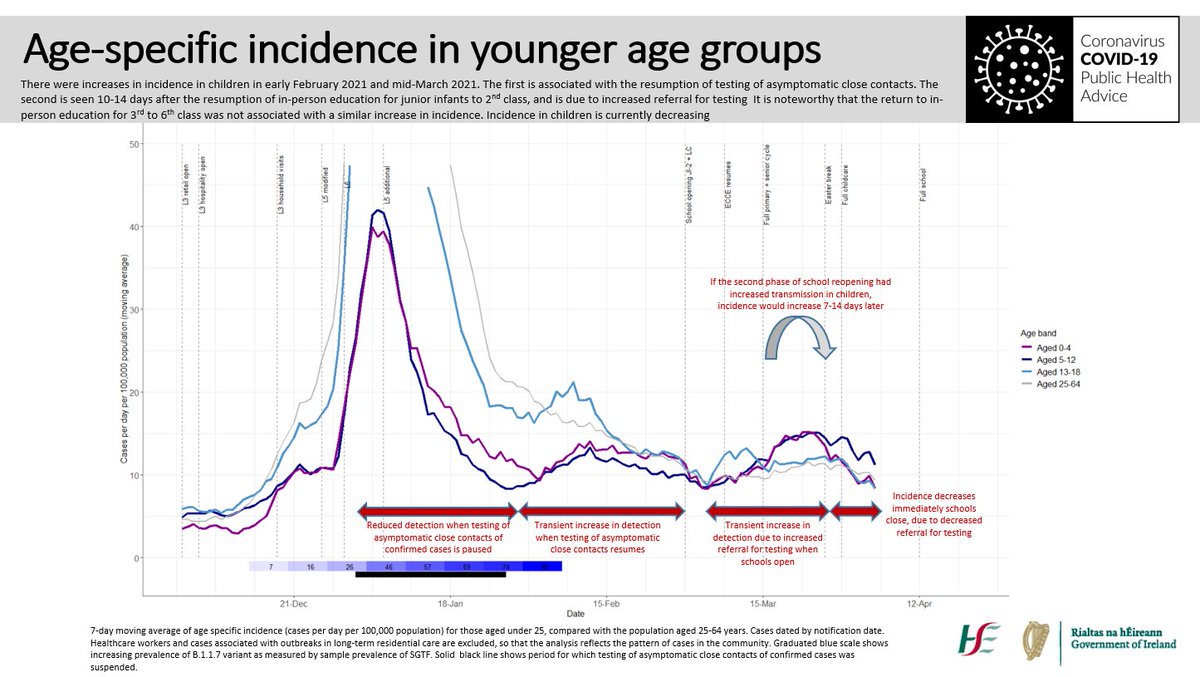

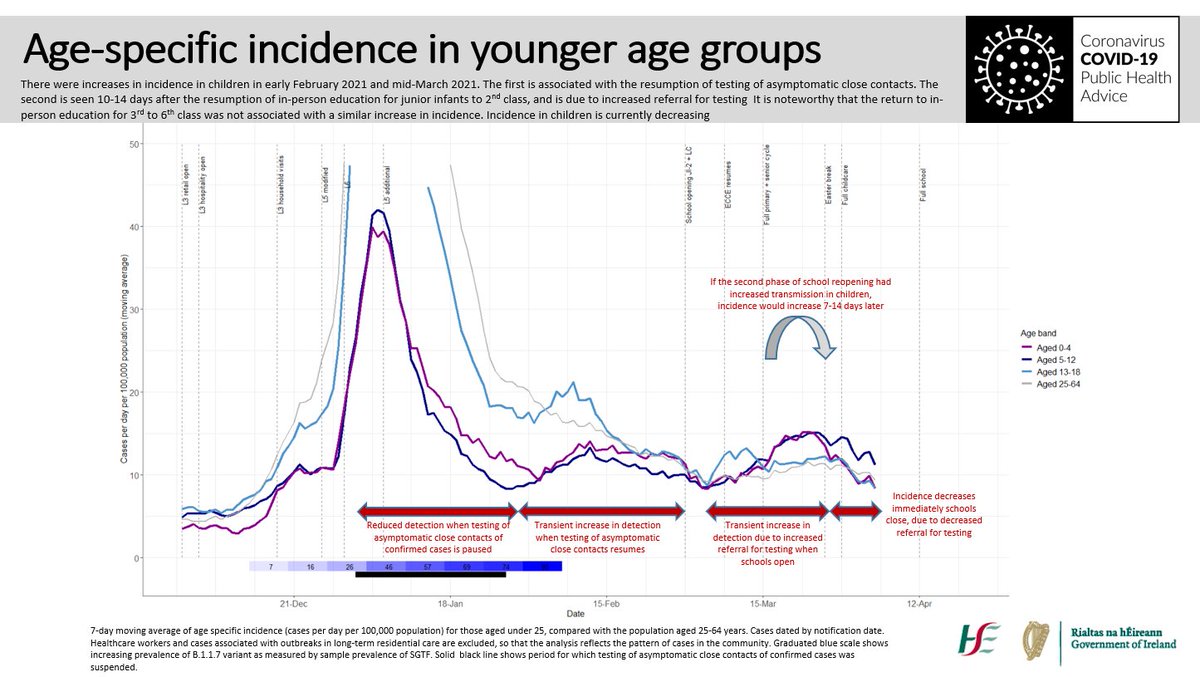

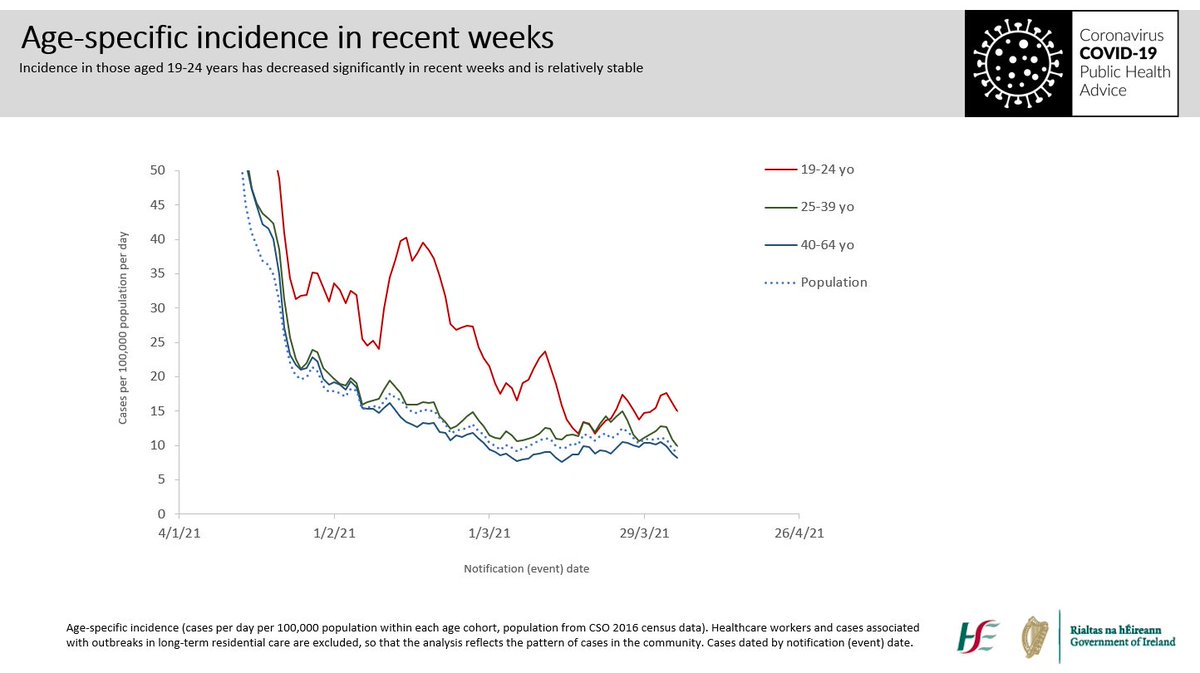

During a surge, incidence in children is generally lower than the population average, but towards the end of the surge it converges with the population average. There have been two recent increases in incidence in children, in early-February and mid-March. 4/16

Specifically, during a surge, we first see incidence rising in 19-24 yo, later and simultaneously in adults 25-64 yo and teenagers, and later again in children, slowly converging on the population average towards the end of the surge. 5/16

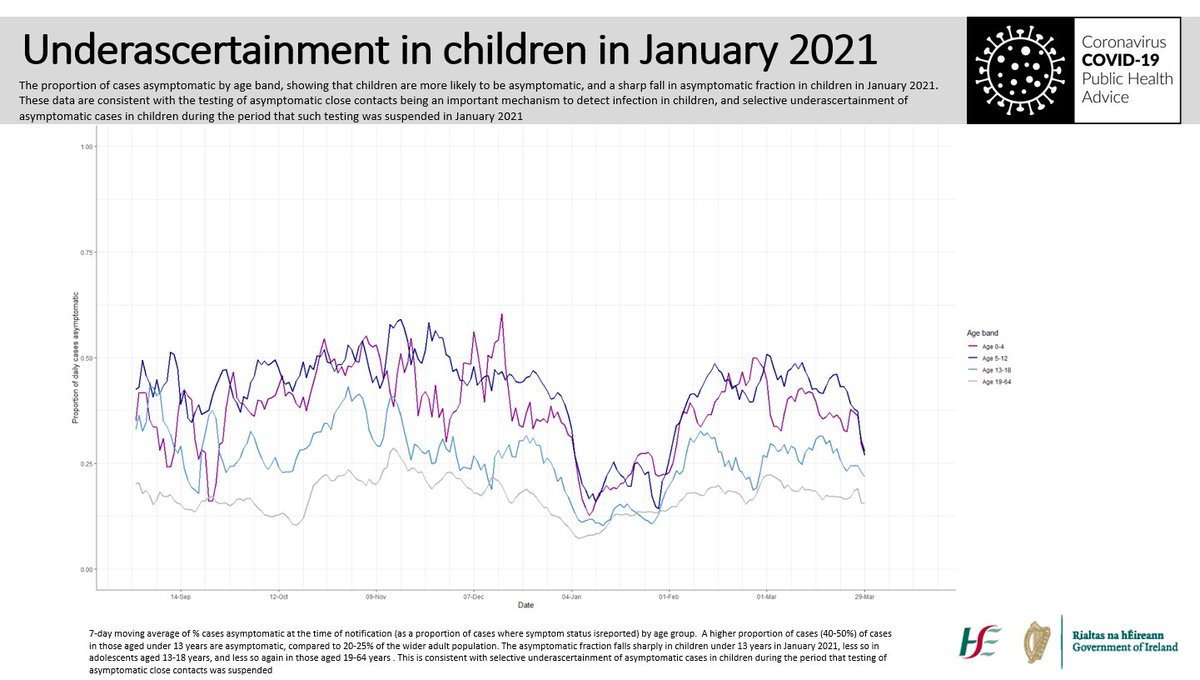

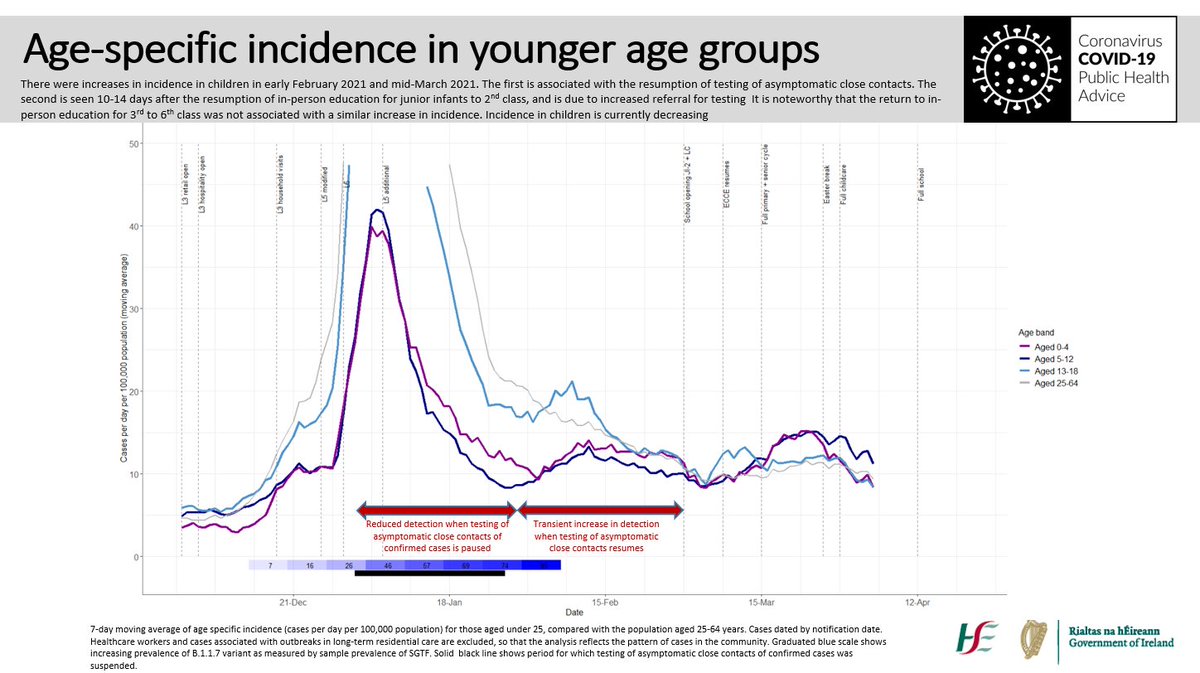

So what explains the recent changes in incidence in children? The first increase occurred in early February, just after we resumed testing of asymptomatic close contacts, which had been paused for most of January. 6/16

Children are more likely to be asymptomatic and the number of asymptomatic infections detected in children dropped sharply in January; so we had undetected cases in January, and the resumption of close contact testing led to an apparent increase in incidence in February. 7/16

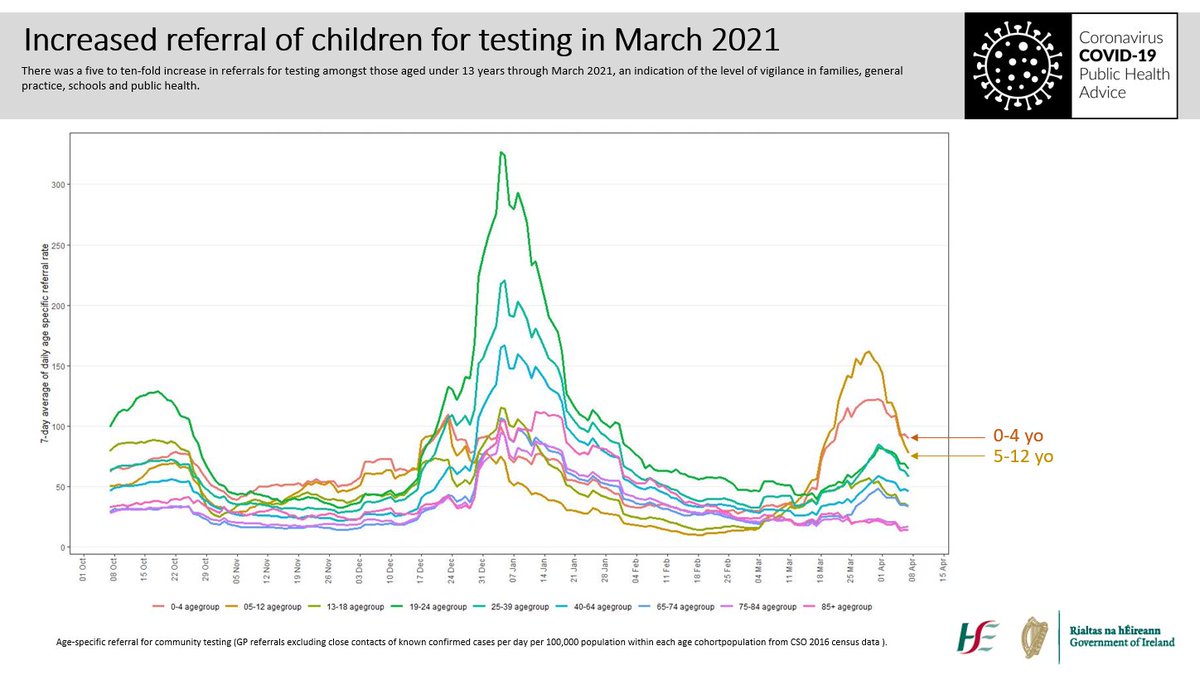

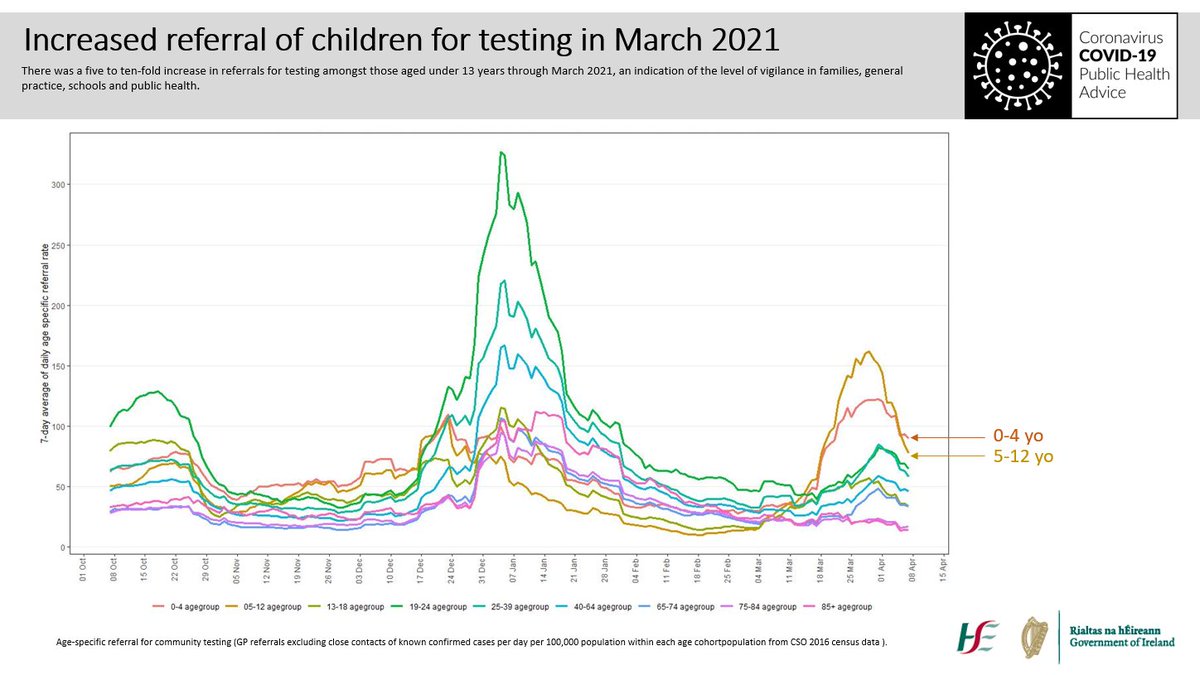

The second increase occurred in mid-March, soon after the first phase of school reopening. It was associated with a very high level of referral for testing, as parents, schools and doctors were vigilant, seeking to protect schools by detecting any infections in children. 8/16

While the level of testing increased 5- to 10- fold, the increase in detected infections was much smaller (40-50%), suggesting that the increase in incidence is in significant part due to the increase in testing (increased case ascertainment). 9/16

This is reinforced by two observations. The second phase of school reopening, from 15 March, involved a similar number of students (over 300,000), yet was not followed by any detectable increase in incidence. 10/16

Incidence started to drop as soon as schools closed for Easter on 26 March. If transmission were occurring in schools, infections occurring in the last week of term would be detected 5-10 days later, during the break. 11/16

The decrease in the number of cases detected during the Easter break is more likely to be due to an immediate drop in the number of referrals of children for testing, as the level of concern (and vigilance) decreases when schools are closed. 12/16

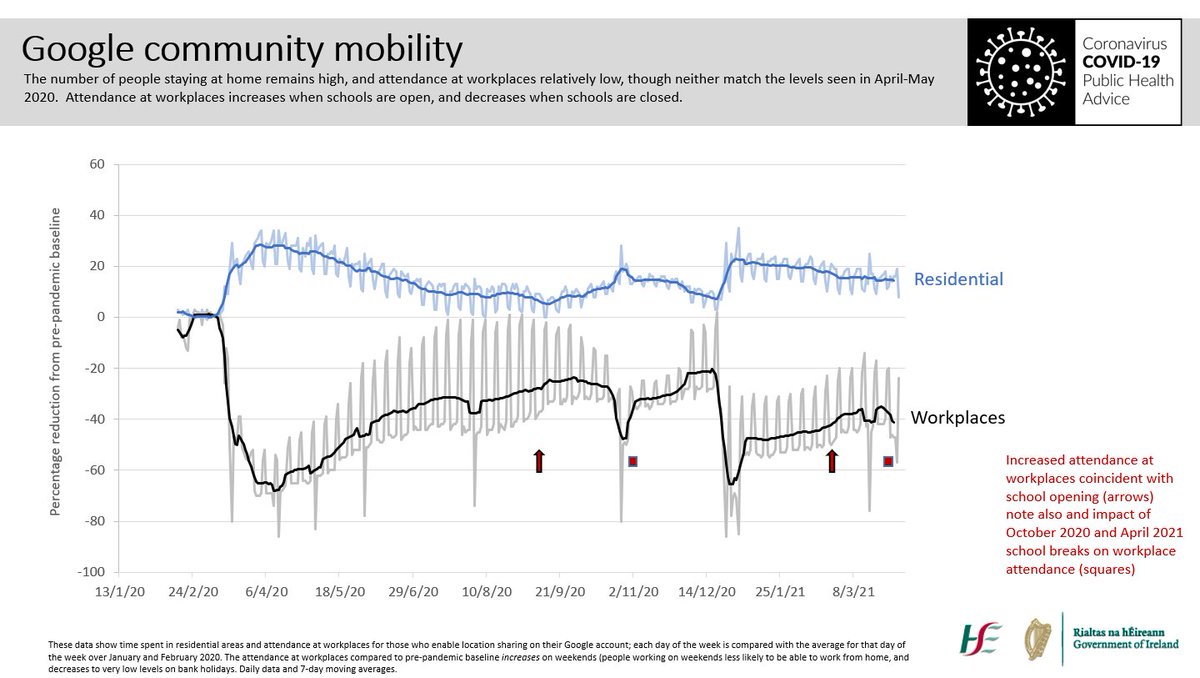

We note also that school opening is associated with an increase in attendance at workplaces; this increase in social mixing amongst adults carries a risk of increased viral transmission between households. 13/16

There has been some concern that the opening of schools may have led to an increase in infection in young adults; there is no population-level signal that this has occurred, with no clear trend in incidence in adults. 14/16

What does this mean? It seems we can return safely to classrooms, with mitigation measures, provided we reduce other contacts, and ensure children who have symptoms, or household members with symptoms, stay out of school and seek medical advice. 15/16

My thanks to the many colleagues in public health, medical laboratory science, surveillance, epidemiology and biostatistics who support the collection and analysis of these data. 16/16

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter