[QT: HOW TO STEAL A PROPHET]

1/101

About a hundred miles from Aurangabad, on NH-222, is a quaint little village called Pathri. Only a few years before the Sepoy Mutiny, the region had been the exclusive domain of various Muslim rulers including the Nizam of Ahmednagar.

1/101

About a hundred miles from Aurangabad, on NH-222, is a quaint little village called Pathri. Only a few years before the Sepoy Mutiny, the region had been the exclusive domain of various Muslim rulers including the Nizam of Ahmednagar.

2/101

The otherwise inconsequential town revived its prominence last year when the Chief Minister extended to it a grant of a billion rupees. Why such an astronomical sum for a town that barely enjoys a spot on the map, much less the minds? Good question, hold on to it for now.

The otherwise inconsequential town revived its prominence last year when the Chief Minister extended to it a grant of a billion rupees. Why such an astronomical sum for a town that barely enjoys a spot on the map, much less the minds? Good question, hold on to it for now.

3/101

Although poor and nondescript, Pathri& #39;s Hindu demography is primarily Brahmin. Not just Brahmins but a very specific subset, Deshastha. And almost all members of this community trace their pedigree to either Yajurvedis or Rigvedis. In short, remarkably homogeneous.

Although poor and nondescript, Pathri& #39;s Hindu demography is primarily Brahmin. Not just Brahmins but a very specific subset, Deshastha. And almost all members of this community trace their pedigree to either Yajurvedis or Rigvedis. In short, remarkably homogeneous.

4/101

A 6-hr drive from Pathri is Mahur, birthplace of Dattatreya, a popular deity in and around Maharashtra. Mahur also houses a temple to Reṇukā Devi, mother of Parashurama. This temple is one of the 51 Hindu Shakti Peethas in existence. And this is the deity Pathri worships.

A 6-hr drive from Pathri is Mahur, birthplace of Dattatreya, a popular deity in and around Maharashtra. Mahur also houses a temple to Reṇukā Devi, mother of Parashurama. This temple is one of the 51 Hindu Shakti Peethas in existence. And this is the deity Pathri worships.

5/101

But while Reṇukā of Mahur is good enough for all Pathri Brahmins, there does exist one exception—the Bhusari family. Albeit also Deshastha Yajurvedis like the rest, the Bhusaris worship Hanuman. Their home, Bhusari House once stood on Vaishnav Lane. No more.

But while Reṇukā of Mahur is good enough for all Pathri Brahmins, there does exist one exception—the Bhusari family. Albeit also Deshastha Yajurvedis like the rest, the Bhusaris worship Hanuman. Their home, Bhusari House once stood on Vaishnav Lane. No more.

6/101

All of what you read hitherto is off a 45-year-old account. The Bhusaris are as gone from Pathri today as their home was in 1975. But this family is important to this thread, for some time in the early 1800s, it birthed a boy child. This child is central to this story.

All of what you read hitherto is off a 45-year-old account. The Bhusaris are as gone from Pathri today as their home was in 1975. But this family is important to this thread, for some time in the early 1800s, it birthed a boy child. This child is central to this story.

7/101

Two more items you might want to keep parked someplace as we proceed are, 1) the Bhusaris& #39; affinity for Hanuman, and 2) Lendi Nadi, a seasonal rivulet that skirts the village and was for long its only source of water. Both these pieces will come together as we proceed.

Two more items you might want to keep parked someplace as we proceed are, 1) the Bhusaris& #39; affinity for Hanuman, and 2) Lendi Nadi, a seasonal rivulet that skirts the village and was for long its only source of water. Both these pieces will come together as we proceed.

8/101

The region Pathri is part of is called Marathwada. There was no Maharashtra until very recently. And there was a time Marathwada itself was part of the Hyderabad kingdom. In fact, the region had spent centuries under various Islamic rulers before taking its modern form.

The region Pathri is part of is called Marathwada. There was no Maharashtra until very recently. And there was a time Marathwada itself was part of the Hyderabad kingdom. In fact, the region had spent centuries under various Islamic rulers before taking its modern form.

9/101

This meant a sustained Islamic influence on the region& #39;s character, both spiritual as well as social. A vast array of sufi cults had enjoyed much currency and prominence in Marathwada that went back centuries. Even today, Muslims make up over half of Pathri& #39;s demography.

This meant a sustained Islamic influence on the region& #39;s character, both spiritual as well as social. A vast array of sufi cults had enjoyed much currency and prominence in Marathwada that went back centuries. Even today, Muslims make up over half of Pathri& #39;s demography.

10/101

Pathri is about 22 miles from Aurangabad which, until the turn of the 20th century, had been one of the epicenters of Deccan Sufism.

It& #39;s against this backdrop, in the mid-1800s, that an 8-year-old boy left his family home in Pathri to tag along with a Sufi mendicant.

Pathri is about 22 miles from Aurangabad which, until the turn of the 20th century, had been one of the epicenters of Deccan Sufism.

It& #39;s against this backdrop, in the mid-1800s, that an 8-year-old boy left his family home in Pathri to tag along with a Sufi mendicant.

11/101

Pathri itself littered with Sufi shrines from that era, a young boy getting drawn into spirituality and mysticism isn& #39;t all that surprising. There are two theories around the identity of the mendicant he left home with, both Sufi mystics or, more accurately, pirs.

Pathri itself littered with Sufi shrines from that era, a young boy getting drawn into spirituality and mysticism isn& #39;t all that surprising. There are two theories around the identity of the mendicant he left home with, both Sufi mystics or, more accurately, pirs.

12/101

One theory identifies him as Hazrat Roshan Shah Miyan, the other as Waris Shah of Dewa in Barabanki, UP. These are just the two dominant theories.

Either way, the mendicant and the boy spent a certain amount of time traveling all over Marathwada doing mendicant things.

One theory identifies him as Hazrat Roshan Shah Miyan, the other as Waris Shah of Dewa in Barabanki, UP. These are just the two dominant theories.

Either way, the mendicant and the boy spent a certain amount of time traveling all over Marathwada doing mendicant things.

13/101

Once done with the mendicant, the boy is said to have landed in Aurangabad and spent a number of years serving one Pir Mohammad as his disciple. It& #39;s during his time in Aurangabad that the boy had a chance encounter with a Muslim gentleman from a nearby village, Dhupkhed.

Once done with the mendicant, the boy is said to have landed in Aurangabad and spent a number of years serving one Pir Mohammad as his disciple. It& #39;s during his time in Aurangabad that the boy had a chance encounter with a Muslim gentleman from a nearby village, Dhupkhed.

14/101

This Muslim gentleman was Chand Patil. As of 1980s, Dhupkhed& #39;s only Muslim inhabitants are those that descended from this gentleman. One of these descendants recounted to author V B Kher that the young boy and Chand Patil had met some 14 miles from Aurangabad.

This Muslim gentleman was Chand Patil. As of 1980s, Dhupkhed& #39;s only Muslim inhabitants are those that descended from this gentleman. One of these descendants recounted to author V B Kher that the young boy and Chand Patil had met some 14 miles from Aurangabad.

15/101

The two are said to have hit it off well and subsequently returned to Chand Patil& #39;s home in Dhupkhed. This house no longer stands today as Chand Patil himself had no child; all his descendants are nephews and nieces. Thence, the boy spent a while in Dhupkhed.

The two are said to have hit it off well and subsequently returned to Chand Patil& #39;s home in Dhupkhed. This house no longer stands today as Chand Patil himself had no child; all his descendants are nephews and nieces. Thence, the boy spent a while in Dhupkhed.

16/101

Here, he& #39;d camp out in the groves by the river on the edge of the village and spend his days wandering and meditating. Then one day, Chand Patil received a marriage proposal for his sister from a village 80 miles to the west. The proposal was accepted.

Here, he& #39;d camp out in the groves by the river on the edge of the village and spend his days wandering and meditating. Then one day, Chand Patil received a marriage proposal for his sister from a village 80 miles to the west. The proposal was accepted.

17/101

The groom& #39;s name was Hamid and his family lived in a rather impoverished village on the fringes of Marathwada& #39;s Sufi realm. The wedding, as is customary, was to be solemnized in this village.

The year could be 1858, 1872, or anything in between. We only have guesstimates.

The groom& #39;s name was Hamid and his family lived in a rather impoverished village on the fringes of Marathwada& #39;s Sufi realm. The wedding, as is customary, was to be solemnized in this village.

The year could be 1858, 1872, or anything in between. We only have guesstimates.

18/101

As Chand Patil& #39;s guest/friend, the boy from Pathri was also invited to join the wedding party. Which he readily accepted.

The wedding finally concluded as planned and Chand Patil returned to Dhupkhed. The guest, however, didn& #39;t. He clearly enjoyed living here.

As Chand Patil& #39;s guest/friend, the boy from Pathri was also invited to join the wedding party. Which he readily accepted.

The wedding finally concluded as planned and Chand Patil returned to Dhupkhed. The guest, however, didn& #39;t. He clearly enjoyed living here.

19/101

Liked it so much, he wound up spending the rest of his life right here. A possible reason could be, he was already familiar with the place. Accounts say he& #39;d already spent three years in this village prior to meeting with Chand Patil.

This village still stands.

Shirdi.

Liked it so much, he wound up spending the rest of his life right here. A possible reason could be, he was already familiar with the place. Accounts say he& #39;d already spent three years in this village prior to meeting with Chand Patil.

This village still stands.

Shirdi.

20/101

There& #39;s also accounts claiming this was the guest& #39;s first trip to Shirdi. Be that as it may, the village did receive him with warmth. At least at first.

Like other villages in the region, Shirdi too had a small Khandoba temple.

Mlahspati was the name of its priest.

There& #39;s also accounts claiming this was the guest& #39;s first trip to Shirdi. Be that as it may, the village did receive him with warmth. At least at first.

Like other villages in the region, Shirdi too had a small Khandoba temple.

Mlahspati was the name of its priest.

21/101

Despite its Hindu character, Shirdi was no stranger to the Sufi influence around. Sufi fakirs weren& #39;t uncommon in the region and they enjoyed much respect even amongst orthodox Brahmins as men of God. India was far more syncretic back in the day than it is today.

Despite its Hindu character, Shirdi was no stranger to the Sufi influence around. Sufi fakirs weren& #39;t uncommon in the region and they enjoyed much respect even amongst orthodox Brahmins as men of God. India was far more syncretic back in the day than it is today.

22/101

So when Chand Patil& #39;s guest, who already looked like a legit Sufi fakir, had his first interface with Mlahspati, the latter found him neither odd nor alien. In fact, the temple priest greeted him with the salutation, "Ya sai!"

It couldn& #39;t get more respectful than that.

So when Chand Patil& #39;s guest, who already looked like a legit Sufi fakir, had his first interface with Mlahspati, the latter found him neither odd nor alien. In fact, the temple priest greeted him with the salutation, "Ya sai!"

It couldn& #39;t get more respectful than that.

23/101

Sai is Sufi-speak for lord. And from that point on, our mendicant from Pathri would forever be called by that name.

That& #39;s the answer to the billion-rupee question you parked earlier.

Shirdi& #39;s inter-faith amity wasn& #39;t without its rough edges though.

Sai is Sufi-speak for lord. And from that point on, our mendicant from Pathri would forever be called by that name.

That& #39;s the answer to the billion-rupee question you parked earlier.

Shirdi& #39;s inter-faith amity wasn& #39;t without its rough edges though.

24/101

Mlahspati was still a Hindu priest.

So when the mendicant tried to enter the temple, Mlahspati& #39;s reverence came in direct conflict with his religious duties.

However exalted, a Muslim couldn& #39;t be let inside a temple!

Awkward.

But it had to be done. So he did.

Mlahspati was still a Hindu priest.

So when the mendicant tried to enter the temple, Mlahspati& #39;s reverence came in direct conflict with his religious duties.

However exalted, a Muslim couldn& #39;t be let inside a temple!

Awkward.

But it had to be done. So he did.

25/101

With much hesitation, Mlahspati refused to let the Baba into the temple. It& #39;s at this point that, Chakor Ajgaonkar says, the latter flew into a rage and asserted his Brahmin identity for the first time, albeit without much in the way of background information.

With much hesitation, Mlahspati refused to let the Baba into the temple. It& #39;s at this point that, Chakor Ajgaonkar says, the latter flew into a rage and asserted his Brahmin identity for the first time, albeit without much in the way of background information.

26/101

Sai is also said to have reprimanded the priest for assuming that a Muslim& #39;s touch would defile a deity who "already touches everything in the world."

Despite his assertions that he was a Brahmin, Sai never quite gave up his Sufi lifestyle.

Sai is also said to have reprimanded the priest for assuming that a Muslim& #39;s touch would defile a deity who "already touches everything in the world."

Despite his assertions that he was a Brahmin, Sai never quite gave up his Sufi lifestyle.

27/101

Along with the Khandoba temple, Shirdi also had a mosque. But while the temple was still in use, the mosque was in ruins. This became Sai& #39;s residence.

He spruced up the place and named it Dwarka Mai Masjid, a deliberate exercise aimed at fostering Hindu-Muslim amity.

Along with the Khandoba temple, Shirdi also had a mosque. But while the temple was still in use, the mosque was in ruins. This became Sai& #39;s residence.

He spruced up the place and named it Dwarka Mai Masjid, a deliberate exercise aimed at fostering Hindu-Muslim amity.

28/101

From this point on, as is public knowledge, Sai continued to preach devotion and peace for the rest of his life, and never left Shirdi even as his fame did.

The Baba& #39;s defining leitmotif, "Allah malik" enjoyed no resistance among Shirdi& #39;s Hindus as it would among Muslims.

From this point on, as is public knowledge, Sai continued to preach devotion and peace for the rest of his life, and never left Shirdi even as his fame did.

The Baba& #39;s defining leitmotif, "Allah malik" enjoyed no resistance among Shirdi& #39;s Hindus as it would among Muslims.

29/101

Now we come to the mendicant& #39;s true identity. The interesting part here isn& #39;t the identity itself but what they& #39;d do with it over time. This is where the rabbit hole begins.

So Sai Baba claimed he was a Brahmin right off the bat as we& #39;ve already seen above.

Now we come to the mendicant& #39;s true identity. The interesting part here isn& #39;t the identity itself but what they& #39;d do with it over time. This is where the rabbit hole begins.

So Sai Baba claimed he was a Brahmin right off the bat as we& #39;ve already seen above.

30/101

This position is shared by a couple of theories and is the dominant one today. How it became dominant is something we& #39;ll come to a little later. Let& #39;s first explore those theories.

The first and the most unanimously held argument comes from one of Sai& #39;s contemporaries.

This position is shared by a couple of theories and is the dominant one today. How it became dominant is something we& #39;ll come to a little later. Let& #39;s first explore those theories.

The first and the most unanimously held argument comes from one of Sai& #39;s contemporaries.

31/101

Govindrao Raghunath Dabholkar—better known as Hemadpant—first came in contact with Sai in the first decade of the 20th century. By then, the Fakir had firmly established as a "servant of God" with a fanbase that spilled way beyond Shirdi& #39;s dusty frontiers.

Govindrao Raghunath Dabholkar—better known as Hemadpant—first came in contact with Sai in the first decade of the 20th century. By then, the Fakir had firmly established as a "servant of God" with a fanbase that spilled way beyond Shirdi& #39;s dusty frontiers.

32/101

The locals had floated numerous tales of Sai& #39;s miracles and consequent divinity, just as they do with godmen today. They made offerings to him, sought his counsel, and sang odes to him. Sai& #39;s response to this deification was an interesting blend of modesty and pragmatism.

The locals had floated numerous tales of Sai& #39;s miracles and consequent divinity, just as they do with godmen today. They made offerings to him, sought his counsel, and sang odes to him. Sai& #39;s response to this deification was an interesting blend of modesty and pragmatism.

33/101

While he consistently denied being God himself, he never forbade them from worshipping him either. His attitude was that of nonchalance. "God is everywhere, so what does it matter who they worship?" was his response when once asked if the deification bothered him.

While he consistently denied being God himself, he never forbade them from worshipping him either. His attitude was that of nonchalance. "God is everywhere, so what does it matter who they worship?" was his response when once asked if the deification bothered him.

34/101

Hemadpant, having met with Sai, decided to pen his biography. So he sought Baba& #39;s permission which the latter is said to have granted promptly. Some fringe accounts claim it was the other way around—that it& #39;s Sai who had asked Hemadpant to pen the biography.

Hemadpant, having met with Sai, decided to pen his biography. So he sought Baba& #39;s permission which the latter is said to have granted promptly. Some fringe accounts claim it was the other way around—that it& #39;s Sai who had asked Hemadpant to pen the biography.

35/101

This biography reaffirms Sai& #39;s Brahmin identity and is the one most widely accepted given its status as a primary source. Per this account, Sai never gave out specifics of his pre-Shirdi life and was particularly vague on questions around his birth. But there& #39;s clues.

This biography reaffirms Sai& #39;s Brahmin identity and is the one most widely accepted given its status as a primary source. Per this account, Sai never gave out specifics of his pre-Shirdi life and was particularly vague on questions around his birth. But there& #39;s clues.

36/101

Pathri. Sai makes it abundantly clear that this is where he was born. He also claims he was born in a Yajurvedi Deshastha Brahmin family.

Now let& #39;s rewind back to where we started this thread. Remember the Bhusaris, the family that once lived on Vaishnav Lane?

Pathri. Sai makes it abundantly clear that this is where he was born. He also claims he was born in a Yajurvedi Deshastha Brahmin family.

Now let& #39;s rewind back to where we started this thread. Remember the Bhusaris, the family that once lived on Vaishnav Lane?

37/101

You& #39;d recall we& #39;d parked two pieces of information on this family before the segue into Deccan Sufism. First, the Bhusaris& #39; oddball devotion to Hanuman in a Reṇukā-worshipping community. This is significant because Sai, despite his Sufi persona, was big on Ram.

You& #39;d recall we& #39;d parked two pieces of information on this family before the segue into Deccan Sufism. First, the Bhusaris& #39; oddball devotion to Hanuman in a Reṇukā-worshipping community. This is significant because Sai, despite his Sufi persona, was big on Ram.

38/101

The second item we& #39;d parked was Lendi, the river that washes around Pathri. Sai aficionados like Kher and Kamath have noted this as the memory behind Shirdi& #39;s own Lendi neighborhood, today called Lendi Baug.

Remember the boy child born to the Bhusari family?

The second item we& #39;d parked was Lendi, the river that washes around Pathri. Sai aficionados like Kher and Kamath have noted this as the memory behind Shirdi& #39;s own Lendi neighborhood, today called Lendi Baug.

Remember the boy child born to the Bhusari family?

39/101

Lendi Baug and Hanuman& #39;s worship establish with near certainty that Sai is that child.

A bonafide Deshastha Brahmin who grew up Sufi.

Why near certainty? Because it still remains a conjecture. A remarkably plausible conjecture, but a conjecture nonetheless.

Lendi Baug and Hanuman& #39;s worship establish with near certainty that Sai is that child.

A bonafide Deshastha Brahmin who grew up Sufi.

Why near certainty? Because it still remains a conjecture. A remarkably plausible conjecture, but a conjecture nonetheless.

40/101

Everything about the Fakir is veiled in mystery a fact that& #39;s a mystery in and of itself given the amount of intimate details the public domain has on his contemporaries like Tilak, Annie Besant, and Phirozshah Mehta.

Let& #39;s begin with his arrival in Shirdi.

Everything about the Fakir is veiled in mystery a fact that& #39;s a mystery in and of itself given the amount of intimate details the public domain has on his contemporaries like Tilak, Annie Besant, and Phirozshah Mehta.

Let& #39;s begin with his arrival in Shirdi.

41/101

Hemadpant& #39;s account, the one Sai devotees hold as canonical today, pins Sai& #39;s first visit to 1854 lasting three years. The second visit, it claims, was in 1858 and lasted until his death in 1918.

But this position is wildly contested by other contemporaries and experts.

Hemadpant& #39;s account, the one Sai devotees hold as canonical today, pins Sai& #39;s first visit to 1854 lasting three years. The second visit, it claims, was in 1858 and lasted until his death in 1918.

But this position is wildly contested by other contemporaries and experts.

42/101

Take B V Narasimha Swami, author of "The Thousand Names Of Shirdi Sai Baba" and a Sai contemporary, for instance. He agrees that Sai& #39;s final trip to Shirdi was with Chand Patil& #39;s sister& #39;s wedding party. But the year this takes place is 1872 and not Hemadpant& #39;s 1858.

Take B V Narasimha Swami, author of "The Thousand Names Of Shirdi Sai Baba" and a Sai contemporary, for instance. He agrees that Sai& #39;s final trip to Shirdi was with Chand Patil& #39;s sister& #39;s wedding party. But the year this takes place is 1872 and not Hemadpant& #39;s 1858.

43/101

The 14-year gap between Hemadpant& #39;s and Swami& #39;s claims is significant. But how did the latter come up with this information? From Ramgir Bua, one of Sai& #39;s first disciples, himself! Ramgir Bua had migrated to Shirdi from Jalgaon and was one of Sai& #39;s close confidants.

The 14-year gap between Hemadpant& #39;s and Swami& #39;s claims is significant. But how did the latter come up with this information? From Ramgir Bua, one of Sai& #39;s first disciples, himself! Ramgir Bua had migrated to Shirdi from Jalgaon and was one of Sai& #39;s close confidants.

44/101

Swami& #39;s claim matches closely with that of V B Kher and M V Kamath who offer the range 1868-1872. The latter also peg the wedding party as Sai& #39;s first trip to Shirdi, not second.

Alison Williams is yet another Sai scholar who echoes this theory albeit her range is wider.

Swami& #39;s claim matches closely with that of V B Kher and M V Kamath who offer the range 1868-1872. The latter also peg the wedding party as Sai& #39;s first trip to Shirdi, not second.

Alison Williams is yet another Sai scholar who echoes this theory albeit her range is wider.

45/101

Let me introduce a new character to the story now—Tatya Kote Patil. This character features in all contemporary accounts including that of Hemadpant.

What makes Tatya relevant is his affinity to Sai whom he affectionately called "mama," (mom& #39;s brother).

Let me introduce a new character to the story now—Tatya Kote Patil. This character features in all contemporary accounts including that of Hemadpant.

What makes Tatya relevant is his affinity to Sai whom he affectionately called "mama," (mom& #39;s brother).

46/101

So, Tatya& #39;s timeline should offer a fair idea of Sai& #39;s. But not much comes from Hemadpant& #39;s account on that front in the way of help. All he mentions is that Tatya& #39;s mom routinely fed a frugal meal of bhakri and veggies to the mad fakir in the woods—that& #39;d be Sai.

So, Tatya& #39;s timeline should offer a fair idea of Sai& #39;s. But not much comes from Hemadpant& #39;s account on that front in the way of help. All he mentions is that Tatya& #39;s mom routinely fed a frugal meal of bhakri and veggies to the mad fakir in the woods—that& #39;d be Sai.

47/101

But that doesn& #39;t tell us anything about Sai& #39;s or even Tatya& #39;s age. So let& #39;s ask Tatya himself.

Sainath Prabha Kiran was a special-interest magazine published out of Shirdi between 1916 and 1919. As the name suggests, it was all about Sai and his teachings.

But that doesn& #39;t tell us anything about Sai& #39;s or even Tatya& #39;s age. So let& #39;s ask Tatya himself.

Sainath Prabha Kiran was a special-interest magazine published out of Shirdi between 1916 and 1919. As the name suggests, it was all about Sai and his teachings.

48/101

The very first issue of this magazine, which came out when Sai was still alive), carried a statement by Tatya recorded by four members of the Dakshina Bhiksha Sanstha. In it, Tatya confirms that Sai raised him since infancy. This is some clue but not yet enough.

The very first issue of this magazine, which came out when Sai was still alive), carried a statement by Tatya recorded by four members of the Dakshina Bhiksha Sanstha. In it, Tatya confirms that Sai raised him since infancy. This is some clue but not yet enough.

49/101

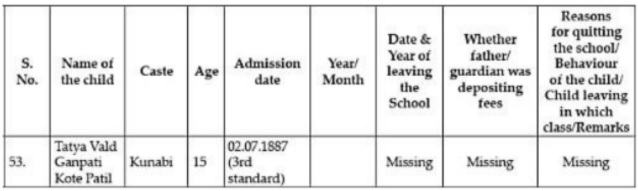

Fortunately, Tatya went to school. So we have his school records for reference.

Tatya& #39;s entry ( #53) in the school& #39;s admission register pegs him as 15 years old in 1887. That means he was born in 1872. So, Sai couldn& #39;t have arrived much before 1872.

Fortunately, Tatya went to school. So we have his school records for reference.

Tatya& #39;s entry ( #53) in the school& #39;s admission register pegs him as 15 years old in 1887. That means he was born in 1872. So, Sai couldn& #39;t have arrived much before 1872.

50/101

The next argument comes from yet another monthly by the name, Shri Sai Leela Maasik Pustak. This magazine& #39;s first issue came out in 1923 and carried a piece by one Hari Sitaram Dixit.

Born in 1864, Dixit was a practicing Nagri Brahmin lawyer from Mumbai.

The next argument comes from yet another monthly by the name, Shri Sai Leela Maasik Pustak. This magazine& #39;s first issue came out in 1923 and carried a piece by one Hari Sitaram Dixit.

Born in 1864, Dixit was a practicing Nagri Brahmin lawyer from Mumbai.

51/101

His first interaction with Sai was during his trip to Shirdi upon the insistence of Nanasaheb Chandorkar, a childhood buddy. That was in 1909.

Fondly referred to as Langda Kaka by Sai, Dixit went on to become one of the first prominent apostles of the fakir.

His first interaction with Sai was during his trip to Shirdi upon the insistence of Nanasaheb Chandorkar, a childhood buddy. That was in 1909.

Fondly referred to as Langda Kaka by Sai, Dixit went on to become one of the first prominent apostles of the fakir.

52/101

A few years after Sai& #39;s death, Kaka started Shri Sai Leela Maasik the first issue of which carried a piece by him titled "Shri Sai Sachcharit" under the pseudonym "Babanche Ek Lekru" (Marathi for "A Child of Baba"). In it, he gives a most direct clue of Sai& #39;s timeline.

A few years after Sai& #39;s death, Kaka started Shri Sai Leela Maasik the first issue of which carried a piece by him titled "Shri Sai Sachcharit" under the pseudonym "Babanche Ek Lekru" (Marathi for "A Child of Baba"). In it, he gives a most direct clue of Sai& #39;s timeline.

53/101

And that direct clue is in the first sentence after opening verses. It says that Sai came to Shirdi around 50 years earlier. Since the issue is dated 1923, that gives us, once again, 1873.

So, thus far, only Hemadpant& #39;s account offers a date that& #39;s outside of 1870s.

And that direct clue is in the first sentence after opening verses. It says that Sai came to Shirdi around 50 years earlier. Since the issue is dated 1923, that gives us, once again, 1873.

So, thus far, only Hemadpant& #39;s account offers a date that& #39;s outside of 1870s.

54/101

That& #39;s six individuals against one. Three of those, contemporaries of Sai. That& #39;s the first hole in the canonical position so far as Sai& #39;s timeline goes. But there& #39;s more.

This one comes from a rather unexpected contemporary—the British. After all, they ruled India.

That& #39;s six individuals against one. Three of those, contemporaries of Sai. That& #39;s the first hole in the canonical position so far as Sai& #39;s timeline goes. But there& #39;s more.

This one comes from a rather unexpected contemporary—the British. After all, they ruled India.

55/101

The Department of Criminal Intelligence was set up at the turn of the 20th century to provide Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India, with intel on revolutionary activities. Headquartered in Calcutta under a Director, part of its job was to publish a weekly report.

The Department of Criminal Intelligence was set up at the turn of the 20th century to provide Lord Curzon, the then Viceroy of India, with intel on revolutionary activities. Headquartered in Calcutta under a Director, part of its job was to publish a weekly report.

56/101

One such report from 1911, speaks of a 70 years old "Mohammedan fakir" in Shirdi who had arrived some 35-40 years earlier. Just so there& #39;s no ambiguity, the report goes on to identify the fakir as Sai Baba and confirms that he lived in a local mosque.

One such report from 1911, speaks of a 70 years old "Mohammedan fakir" in Shirdi who had arrived some 35-40 years earlier. Just so there& #39;s no ambiguity, the report goes on to identify the fakir as Sai Baba and confirms that he lived in a local mosque.

57/101

This report is in direct conflict with Dabholkar& #39;s Shri Sai Satcharita on several key issues. We& #39;ve already seen the conflict on Sai& #39;s date of arrival. But it also differs on Sai& #39;s age when he arrived as well as whether it was his first visit or second. And his birthdate.

This report is in direct conflict with Dabholkar& #39;s Shri Sai Satcharita on several key issues. We& #39;ve already seen the conflict on Sai& #39;s date of arrival. But it also differs on Sai& #39;s age when he arrived as well as whether it was his first visit or second. And his birthdate.

58/101

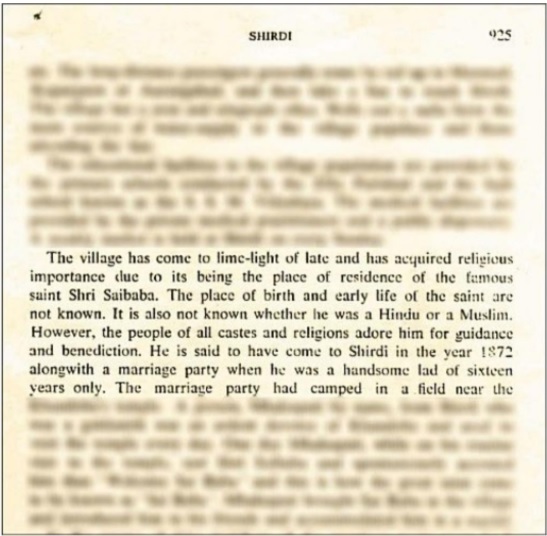

The final piece of evidence that the marriage party Sai accompanied to Shirdi was in 1872 comes from none other than the Government of Maharashtra. It& #39;s the Ahmadnagar section of a 1976 gazetteer report. Although it remains fuzzy on Baba& #39;s religion, it& #39;s clear on 1872.

The final piece of evidence that the marriage party Sai accompanied to Shirdi was in 1872 comes from none other than the Government of Maharashtra. It& #39;s the Ahmadnagar section of a 1976 gazetteer report. Although it remains fuzzy on Baba& #39;s religion, it& #39;s clear on 1872.

59/101

But why is Sai& #39;s timeline so important anyway?

The answer to that question is another question—Is Dabholkar& #39;s work historical or panegyric? Because if it& #39;s the former, there& #39;s no room for ambiguity, especially on such crucial milestones of Sai& #39;s life. If not, well...

But why is Sai& #39;s timeline so important anyway?

The answer to that question is another question—Is Dabholkar& #39;s work historical or panegyric? Because if it& #39;s the former, there& #39;s no room for ambiguity, especially on such crucial milestones of Sai& #39;s life. If not, well...

60/101

Almost all of Sai& #39;s contemporary retellers, including Dabholkar, agree on one thing though: That his lineage is ambiguous at best. Sai himself is said to have often claimed origins from the Brahmin family in Pathri, likely the one we discussed earlier. And vehemently so.

Almost all of Sai& #39;s contemporary retellers, including Dabholkar, agree on one thing though: That his lineage is ambiguous at best. Sai himself is said to have often claimed origins from the Brahmin family in Pathri, likely the one we discussed earlier. And vehemently so.

61/101

However, that doesn& #39;t jive with his lifestyle as recorded by the same sources. While the British straight-up reported him as a Muslim fakir, Hemadpant& #39;s account makes several references to Sai& #39;s Muslim ways. His taking up residence in a mosque is just one of many.

However, that doesn& #39;t jive with his lifestyle as recorded by the same sources. While the British straight-up reported him as a Muslim fakir, Hemadpant& #39;s account makes several references to Sai& #39;s Muslim ways. His taking up residence in a mosque is just one of many.

62/101

Dabholkar wrote Shri Sai Satcharita entirely in Marathi. The text was translated into English for a wider audience in 1944 by one Nagesh Gunaji. Both Marathi, as well as English, versions make no fewer than a dozen references to Allah. But that could just be incidental.

Dabholkar wrote Shri Sai Satcharita entirely in Marathi. The text was translated into English for a wider audience in 1944 by one Nagesh Gunaji. Both Marathi, as well as English, versions make no fewer than a dozen references to Allah. But that could just be incidental.

63/101

So let& #39;s visit Hemadpant& #39;s book.

Chapter 23. Last section.

Here, Hemadpant recounts an episode where Sai asked his disciples to slaughter a goat for mutton. One of them was Kakasaheb Dixit, a Brahmin, and the other was Haji Pir Mohammad of Malegaon.

So let& #39;s visit Hemadpant& #39;s book.

Chapter 23. Last section.

Here, Hemadpant recounts an episode where Sai asked his disciples to slaughter a goat for mutton. One of them was Kakasaheb Dixit, a Brahmin, and the other was Haji Pir Mohammad of Malegaon.

64/101

Funnily enough, Pir Mohammad declined while Kakasaheb, a meat-shunning Brahmin, proceeded to comply. Just before the latter could begin the slaughter, though, Sai intervened and said he& #39;d do it himself. The goat was then taken to a place named Takkiya and disposed of.

Funnily enough, Pir Mohammad declined while Kakasaheb, a meat-shunning Brahmin, proceeded to comply. Just before the latter could begin the slaughter, though, Sai intervened and said he& #39;d do it himself. The goat was then taken to a place named Takkiya and disposed of.

65/101

Takkiya, by the way, is where the Muslims of Shirdi buried their dead back in the day. Sai& #39;s choice of this specific spot is pertinent to Baba& #39;s religious identity. Besides his choice of residence, that is. But even more pertinent is the very idea of slaughter itself.

Takkiya, by the way, is where the Muslims of Shirdi buried their dead back in the day. Sai& #39;s choice of this specific spot is pertinent to Baba& #39;s religious identity. Besides his choice of residence, that is. But even more pertinent is the very idea of slaughter itself.

66/101

It& #39;s extremely unlikely for a 19th century Brahmin guru to even consider animal slaughter by any stretch of the imagination. Even as a test of devotion. Even if just for food.

And yet, this isn& #39;t the only reference to meat in the entire canon. There& #39;s one more.

It& #39;s extremely unlikely for a 19th century Brahmin guru to even consider animal slaughter by any stretch of the imagination. Even as a test of devotion. Even if just for food.

And yet, this isn& #39;t the only reference to meat in the entire canon. There& #39;s one more.

67/101

Chapter 38 (Baba& #39;s Handi, final chapter)

This chapter goes into the details of Baba& #39;s Chavadi procession. Baba would, according to this account, routinely feed a large contingent of devotees and visitors with a wholesome meal of both meat and plant-based dishes.

Chapter 38 (Baba& #39;s Handi, final chapter)

This chapter goes into the details of Baba& #39;s Chavadi procession. Baba would, according to this account, routinely feed a large contingent of devotees and visitors with a wholesome meal of both meat and plant-based dishes.

68/101

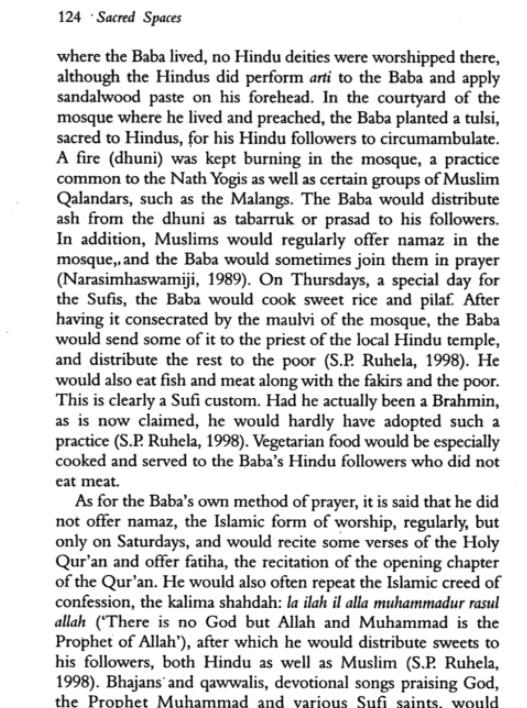

The chapter specifies that the Baba was not just a supervisor but an active participant in the entire activity—shopping, cooking, and feeding. He did it all with his own hands. This included meat for meat-eaters.

Again, inconceivable for a spiritual Brahmin even today.

The chapter specifies that the Baba was not just a supervisor but an active participant in the entire activity—shopping, cooking, and feeding. He did it all with his own hands. This included meat for meat-eaters.

Again, inconceivable for a spiritual Brahmin even today.

69/101

Do note, though, that the Baba himself never ate meat.

Moving on...

Around 1890, Shirdi had another visitor important to this thread—a 20-year-old Muslim boy named Abdul.

Abdul, too, was a mendicant who had left home on a spiritual journey at an early age.

Do note, though, that the Baba himself never ate meat.

Moving on...

Around 1890, Shirdi had another visitor important to this thread—a 20-year-old Muslim boy named Abdul.

Abdul, too, was a mendicant who had left home on a spiritual journey at an early age.

70/101

Just as Sai had tagged along with a Sufi Fakir before landing in Shirdi, Abdul had been traveling with a Nanded Sufi by the name Ameeruddin.

Legends say it& #39;s Amiruddin who sent Abdul to Shirdi after Sai showed up in his dream. But that& #39;s not of import here.

Just as Sai had tagged along with a Sufi Fakir before landing in Shirdi, Abdul had been traveling with a Nanded Sufi by the name Ameeruddin.

Legends say it& #39;s Amiruddin who sent Abdul to Shirdi after Sai showed up in his dream. But that& #39;s not of import here.

71/101

Abdul quickly, if not instantly, became a personal favorite of Sai. He lived in a stable next to the mosque where Sai lived and served the latter as a devout servitor.

Baba would often ask him to recite the Holy Qur& #39;an for him and make notes. This was a routine affair.

Abdul quickly, if not instantly, became a personal favorite of Sai. He lived in a stable next to the mosque where Sai lived and served the latter as a devout servitor.

Baba would often ask him to recite the Holy Qur& #39;an for him and make notes. This was a routine affair.

72/101

Abdul, fondly known as Abdul Baba even today, was to Sai what Peter was to Jesus. And yet, funnily enough, his affinity to Sai barely finds a mention in Dabholkar& #39;s account. He IS mentioned—a total of 9 times—but only as one of Sai& #39;s devotees, not a close comrade.

Abdul, fondly known as Abdul Baba even today, was to Sai what Peter was to Jesus. And yet, funnily enough, his affinity to Sai barely finds a mention in Dabholkar& #39;s account. He IS mentioned—a total of 9 times—but only as one of Sai& #39;s devotees, not a close comrade.

73/101

Another interesting facet of Sai& #39;s ways comes from Chandorkar, the same gentleman who had introduced Dixit to the holy man. Per him, Sai& #39;s preaching had a distinct Islamic character and his utterances were all in Persian or Arabic. No Sanskrit mantras or Vedic verses.

Another interesting facet of Sai& #39;s ways comes from Chandorkar, the same gentleman who had introduced Dixit to the holy man. Per him, Sai& #39;s preaching had a distinct Islamic character and his utterances were all in Persian or Arabic. No Sanskrit mantras or Vedic verses.

74/101

Dabholkar or Hemadpant, by the way, wasn& #39;t the only one recording Baba& #39;s activities and teachings. Abdul did it too.

The latter wrote in Urdu and opened each chapter with a customary Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim, an ode to Allah, followed by another to Prophet Mohammad.

Dabholkar or Hemadpant, by the way, wasn& #39;t the only one recording Baba& #39;s activities and teachings. Abdul did it too.

The latter wrote in Urdu and opened each chapter with a customary Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim, an ode to Allah, followed by another to Prophet Mohammad.

75/101

This manuscript, when completed, ran 200 pages and is still in possession of Abdul& #39;s descendants. Tragically, though, it never made it into the Sai canon. In fact, much of it has been lost to the wear and tear of time and lack of import. One can only guess the reasons.

This manuscript, when completed, ran 200 pages and is still in possession of Abdul& #39;s descendants. Tragically, though, it never made it into the Sai canon. In fact, much of it has been lost to the wear and tear of time and lack of import. One can only guess the reasons.

76/101

Sai died, or as the prevalent semantic goes, "attained mahasamadhi" in October 1918.

Those were volatile years. India& #39;s first wave of Hindu nationalism had only recently crystallized as the Hindu Mahasabha. The movement was gaining momentum and with it, communal tension.

Sai died, or as the prevalent semantic goes, "attained mahasamadhi" in October 1918.

Those were volatile years. India& #39;s first wave of Hindu nationalism had only recently crystallized as the Hindu Mahasabha. The movement was gaining momentum and with it, communal tension.

77/101

Although the Mahasabha originated up north in Haridwar, it& #39;s Maharashtra that was rapidly becoming the true laboratory of Hindu nationalism. Tilak, who was already in his 60s then, was actively spearheading the campaign here. It& #39;s against this backdrop that Sai died.

Although the Mahasabha originated up north in Haridwar, it& #39;s Maharashtra that was rapidly becoming the true laboratory of Hindu nationalism. Tilak, who was already in his 60s then, was actively spearheading the campaign here. It& #39;s against this backdrop that Sai died.

78/101

Officially, Sai left behind no heir, no will. There was no successor. But largely untouched by the communal anxiety in its vicinity, Shirdi didn& #39;t mind Abdul Baba taking his spot.

But before we get to that, a bit on Sai& #39;s post-death rites.

Officially, Sai left behind no heir, no will. There was no successor. But largely untouched by the communal anxiety in its vicinity, Shirdi didn& #39;t mind Abdul Baba taking his spot.

But before we get to that, a bit on Sai& #39;s post-death rites.

79/101

Gopalrao Mukund was a well-known lawyer and popularly known as Bapusaheb Buti, the multi-millionnaire of Nagpur. This gentleman paid his first visit to Shirdi, allegedly on a vision, in 1910. That& #39;s just a year after another lawyer—Dixit, who came from Bombay.

Gopalrao Mukund was a well-known lawyer and popularly known as Bapusaheb Buti, the multi-millionnaire of Nagpur. This gentleman paid his first visit to Shirdi, allegedly on a vision, in 1910. That& #39;s just a year after another lawyer—Dixit, who came from Bombay.

80/101

Used to the material luxuries of life, Buti decided to build himself a comfortable abode in Shirdi since it was to be his home for the rest of his life. The plan was to have Sai live with him in that house, a far cozier dwelling than the mosque he was living in.

Used to the material luxuries of life, Buti decided to build himself a comfortable abode in Shirdi since it was to be his home for the rest of his life. The plan was to have Sai live with him in that house, a far cozier dwelling than the mosque he was living in.

81/101

The project began in 1915 under Sai& #39;s regular supervision and rose quickly. They named it Buti Wada.

At one point, Buti sought Sai& #39;s nod on installing a Krishna figure inside the newly constructed building. For some reason, Sai shot down the idea almost right away.

The project began in 1915 under Sai& #39;s regular supervision and rose quickly. They named it Buti Wada.

At one point, Buti sought Sai& #39;s nod on installing a Krishna figure inside the newly constructed building. For some reason, Sai shot down the idea almost right away.

82/101

October 15, 1918.

Sai died.

Hindus cremate their dead, Muslims bury theirs. Sai& #39;s death threw his congregation into a fix. What rites to follow? After much deliberation, it was decided to bury him inside Buti Wada, given Sai& #39;s involvement with its construction.

October 15, 1918.

Sai died.

Hindus cremate their dead, Muslims bury theirs. Sai& #39;s death threw his congregation into a fix. What rites to follow? After much deliberation, it was decided to bury him inside Buti Wada, given Sai& #39;s involvement with its construction.

83/101

His "samadhi" resembled the archetypal mazaar Sufi pirs and holy men are given when they die.

As for Abdul Baba, he was unanimously appointed the tomb& #39;s custodian. Just another illustration of his intimacy with the dead saint and the acceptance of Sai& #39;s Muslim identity.

His "samadhi" resembled the archetypal mazaar Sufi pirs and holy men are given when they die.

As for Abdul Baba, he was unanimously appointed the tomb& #39;s custodian. Just another illustration of his intimacy with the dead saint and the acceptance of Sai& #39;s Muslim identity.

84/101

Abdul continued to diligently perform his custodian duties at the Wada every day—placing fresh flowers on the mazaar, changing the "chaadar," and generally sprucing up the place.

Buti still owned the place and continued to pay 500 rupees toward annual maintenance.

Abdul continued to diligently perform his custodian duties at the Wada every day—placing fresh flowers on the mazaar, changing the "chaadar," and generally sprucing up the place.

Buti still owned the place and continued to pay 500 rupees toward annual maintenance.

85/101

But that doesn& #39;t mean nobody had reservations.

The 1920s had brought radical Hindutva to Shirdi, firmly entrenched in Nagpur, Aurangabad, and Nashik. Sai& #39;s base couldn& #39;t stay unaffected for too long. It was only a matter of time and faultlines had already begun to appear.

But that doesn& #39;t mean nobody had reservations.

The 1920s had brought radical Hindutva to Shirdi, firmly entrenched in Nagpur, Aurangabad, and Nashik. Sai& #39;s base couldn& #39;t stay unaffected for too long. It was only a matter of time and faultlines had already begun to appear.

86/101

In 1921, on Sai& #39;s third death anniversary, Kaka Dixit and his cohorts established a formal governing body to manage Sai& #39;s physical legacy—Shri Saibaba Sansthan.

This was to come, by some accounts, as a body blow to Abdul Baba as he would no longer be the custodian.

In 1921, on Sai& #39;s third death anniversary, Kaka Dixit and his cohorts established a formal governing body to manage Sai& #39;s physical legacy—Shri Saibaba Sansthan.

This was to come, by some accounts, as a body blow to Abdul Baba as he would no longer be the custodian.

87/101

Sathpathy observes that Abdul was from that point on ousted not only from Sai& #39;s inheritance but also the Wada. While this may or may not be an exaggeration, the process did involve a legal battle. The Sansthan only formed after the Ahmednagar Judge& #39;s approval.

Sathpathy observes that Abdul was from that point on ousted not only from Sai& #39;s inheritance but also the Wada. While this may or may not be an exaggeration, the process did involve a legal battle. The Sansthan only formed after the Ahmednagar Judge& #39;s approval.

88/101

And this is where Sai& #39;s saffronization began. The Wada, which hitherto sported a distinct Dargah-like character, was now a mandir. Over time, more Hindu elements were added. What used to be an understated tomb was now an altar with a marble Sai statue decked in flowers.

And this is where Sai& #39;s saffronization began. The Wada, which hitherto sported a distinct Dargah-like character, was now a mandir. Over time, more Hindu elements were added. What used to be an understated tomb was now an altar with a marble Sai statue decked in flowers.

89/101

So the question you might ask now is, was Sai Muslim?

And if this thread is anything to go by, you& #39;ve perhaps concluded in the affirmative.

But that& #39;s neither the right conclusion nor the right question. Sufis are a complicated people. Not easy to pigeonhole them thus.

So the question you might ask now is, was Sai Muslim?

And if this thread is anything to go by, you& #39;ve perhaps concluded in the affirmative.

But that& #39;s neither the right conclusion nor the right question. Sufis are a complicated people. Not easy to pigeonhole them thus.

90/101

Sure, there are many, many indications of Sai& #39;s Muslim identity in nearly all accounts. But there are just as many of his Hindu identity. We may lean one way or the other driven by our own preferences, but Sai& #39;s true identity was, at best, fluid.

Sure, there are many, many indications of Sai& #39;s Muslim identity in nearly all accounts. But there are just as many of his Hindu identity. We may lean one way or the other driven by our own preferences, but Sai& #39;s true identity was, at best, fluid.

91/101

He never ate meat. But he didn& #39;t mind feeding it to others. He insisted he was a Brahmin, but he was fluent with the Qur& #39;an. He fawned over Ram, but also kept saying "Allah malik." He lit diyas every evening, but lived in a mosque. He was a pleasant bag of contradictions.

He never ate meat. But he didn& #39;t mind feeding it to others. He insisted he was a Brahmin, but he was fluent with the Qur& #39;an. He fawned over Ram, but also kept saying "Allah malik." He lit diyas every evening, but lived in a mosque. He was a pleasant bag of contradictions.

92/101

And that& #39;s how Sufis are. Technically, he may or may not have been a Muslim by birth. But his legacy certainly isn& #39;t.

So why this thread?

To shine a bright light. Not on Sai but on his communally questionable legacy. On how he was stolen by saffron strongmen.

And that& #39;s how Sufis are. Technically, he may or may not have been a Muslim by birth. But his legacy certainly isn& #39;t.

So why this thread?

To shine a bright light. Not on Sai but on his communally questionable legacy. On how he was stolen by saffron strongmen.

93/101

The Sansthan formed in 1922 was conveniently composed of Hindus. Entirely. Not one non-Hindu member.

Not even Abdul.

Some say Abdul was still respected, others say he was discarded. I& #39;m not sure what to follow, but he sure wasn& #39;t part of the new trust.

The Sansthan formed in 1922 was conveniently composed of Hindus. Entirely. Not one non-Hindu member.

Not even Abdul.

Some say Abdul was still respected, others say he was discarded. I& #39;m not sure what to follow, but he sure wasn& #39;t part of the new trust.

94/101

While in due time, Abdul Baba did regain some of his lost esteem and today even has a dargah, the Muslim claim to Sai& #39;s syncretic legacy stands irretrievably diminished. Sai never supported idolatry, possibly why he straight-up denied the Krishna statue at Buti Wada.

While in due time, Abdul Baba did regain some of his lost esteem and today even has a dargah, the Muslim claim to Sai& #39;s syncretic legacy stands irretrievably diminished. Sai never supported idolatry, possibly why he straight-up denied the Krishna statue at Buti Wada.

95/101

But today, his shrine sports not only his own statue but also an image of Ram. While Sai did worship Ram and Hanuman, he never approved of their idols or pictures.

Abdul may have enjoyed some regard in later years, but his manuscript remained unpublished. And neglected.

But today, his shrine sports not only his own statue but also an image of Ram. While Sai did worship Ram and Hanuman, he never approved of their idols or pictures.

Abdul may have enjoyed some regard in later years, but his manuscript remained unpublished. And neglected.

96/101

The Sansthan that was formed with less than 4,000 rupees in 1922 raked in 3 billion in 2019 alone, placing it among the wealthiest Hindu temples on Earth.

What should& #39;ve been a beacon of communal harmony became a cornucopia of tax-free bounty. With zero accountability.

The Sansthan that was formed with less than 4,000 rupees in 1922 raked in 3 billion in 2019 alone, placing it among the wealthiest Hindu temples on Earth.

What should& #39;ve been a beacon of communal harmony became a cornucopia of tax-free bounty. With zero accountability.

97/101

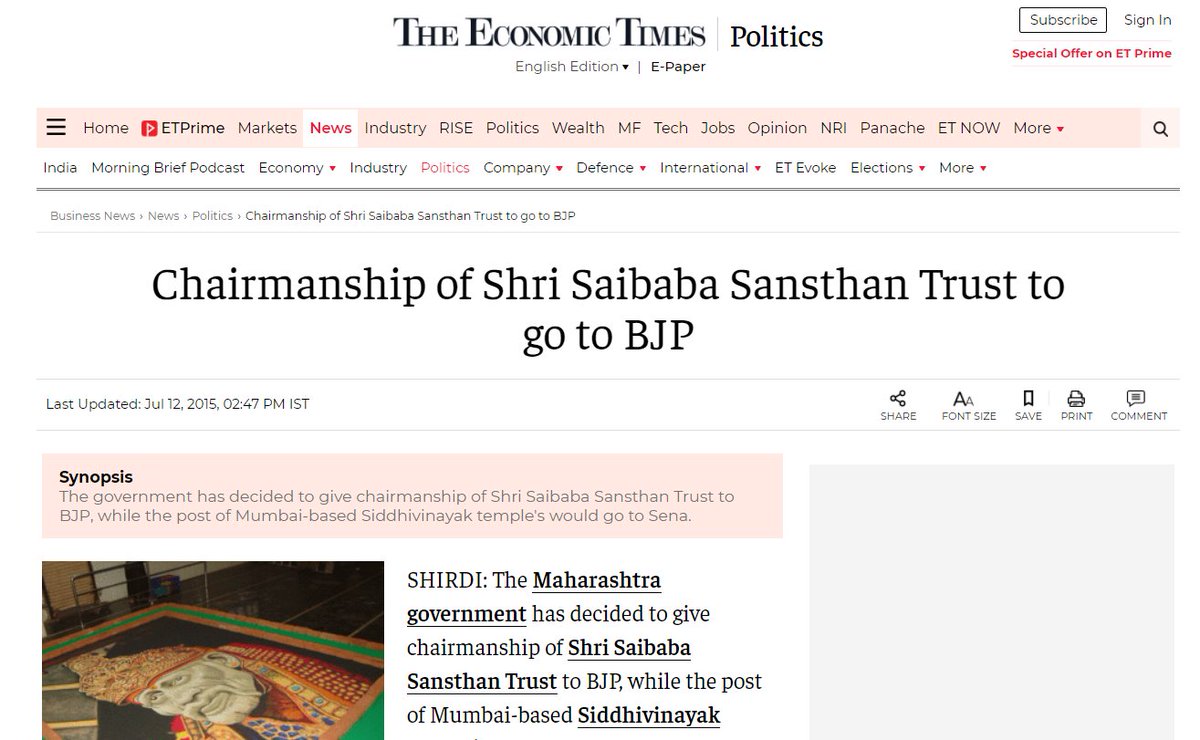

And in 2015, this cornucopia officially went to the only openly saffron political outfit in India, a veritable black hole of donations in its own right.

What do you think this would& #39;ve done to the non-Hindu part of Sai& #39;s legacy if any? Rhetorical.

https://bit.ly/3wFChcT ">https://bit.ly/3wFChcT&q...

And in 2015, this cornucopia officially went to the only openly saffron political outfit in India, a veritable black hole of donations in its own right.

What do you think this would& #39;ve done to the non-Hindu part of Sai& #39;s legacy if any? Rhetorical.

https://bit.ly/3wFChcT ">https://bit.ly/3wFChcT&q...

98/101

Sai& #39;s "handi," even by the most hagiographical of records included meat liberally. Today meat is forbidden in all of Shirdi. Again, what happens to Sai& #39;s non-Hindu legacy? Again, rhetorical.

Funnily enough, though, your monsters must eventually turn on you.

Sai& #39;s "handi," even by the most hagiographical of records included meat liberally. Today meat is forbidden in all of Shirdi. Again, what happens to Sai& #39;s non-Hindu legacy? Again, rhetorical.

Funnily enough, though, your monsters must eventually turn on you.

99/101

Remember the recent news of vandalism at a Sai temple in Delhi by saffron goons? Egged on by a "priest" from Ghaziabad, UP, they claimed he was no god. Words like "mullah" and "jihadi" were heard.

At this point, ask yourself as a Sai devotee, would he be pleased?

Remember the recent news of vandalism at a Sai temple in Delhi by saffron goons? Egged on by a "priest" from Ghaziabad, UP, they claimed he was no god. Words like "mullah" and "jihadi" were heard.

At this point, ask yourself as a Sai devotee, would he be pleased?

100/101

So that& #39;s the unfortunate story of a man who did his bit to bring two incompatible peoples together with his version of divinity.

A man whose legacy was systematically stolen by one community for power, money, and political hegemony.

So that& #39;s the unfortunate story of a man who did his bit to bring two incompatible peoples together with his version of divinity.

A man whose legacy was systematically stolen by one community for power, money, and political hegemony.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter![[QT: HOW TO STEAL A PROPHET]1/101About a hundred miles from Aurangabad, on NH-222, is a quaint little village called Pathri. Only a few years before the Sepoy Mutiny, the region had been the exclusive domain of various Muslim rulers including the Nizam of Ahmednagar. [QT: HOW TO STEAL A PROPHET]1/101About a hundred miles from Aurangabad, on NH-222, is a quaint little village called Pathri. Only a few years before the Sepoy Mutiny, the region had been the exclusive domain of various Muslim rulers including the Nizam of Ahmednagar.](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/EybhVG6VIAgefde.jpg)