The art community has been having a really hard time recently. There is one thing that, I believe, we can agree on, and that& #39;s the beauty of artistic fundamentals.

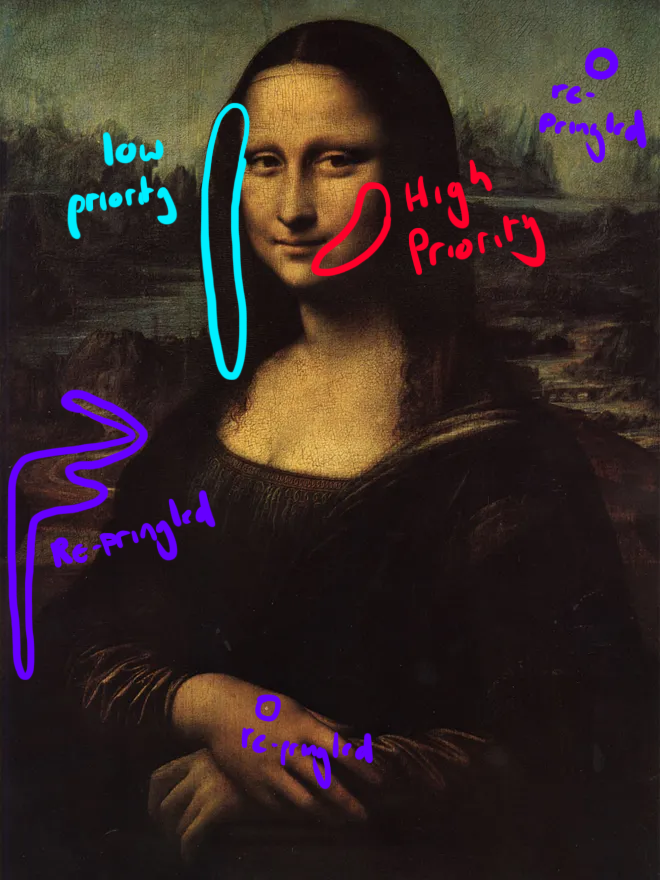

I& #39;m going to spend some time today talking about my favourite, somewhat underappreciated fundamental; Repringling.

I& #39;m going to spend some time today talking about my favourite, somewhat underappreciated fundamental; Repringling.

Pringling, as we all know, occurs in low to high frequency fields within artworks.

This has nothing to do with the potato chip named Pringles. Please cast them from your mind at this point if you are unfamiliar with Pringling.

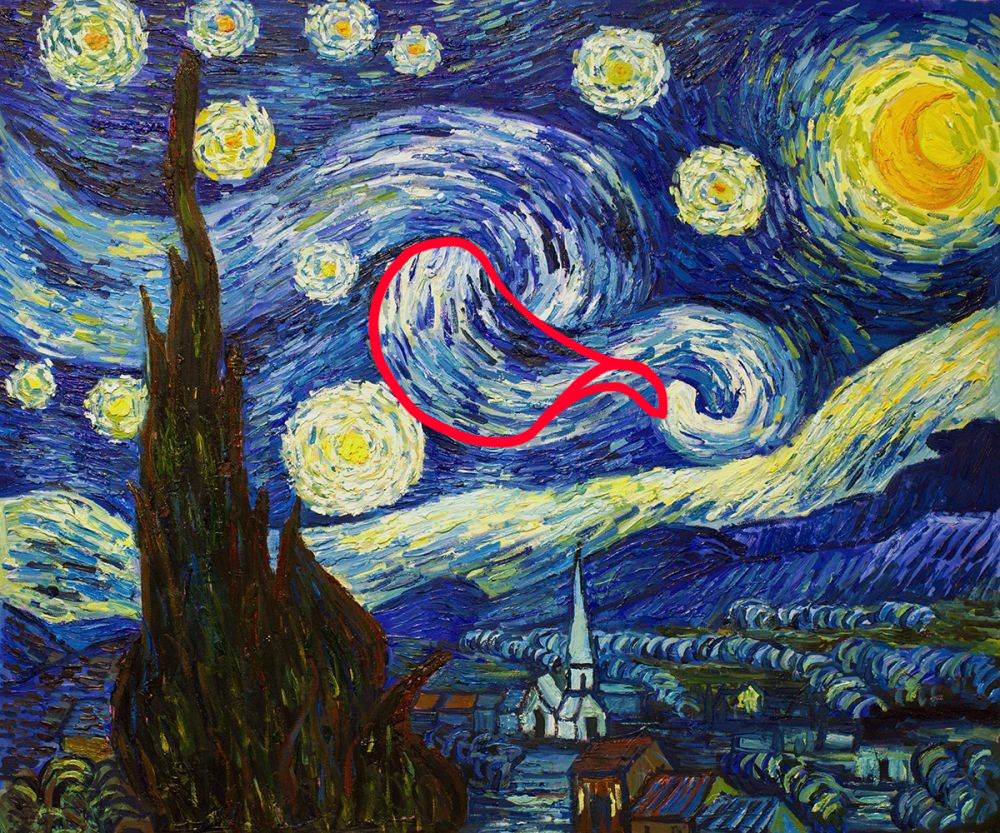

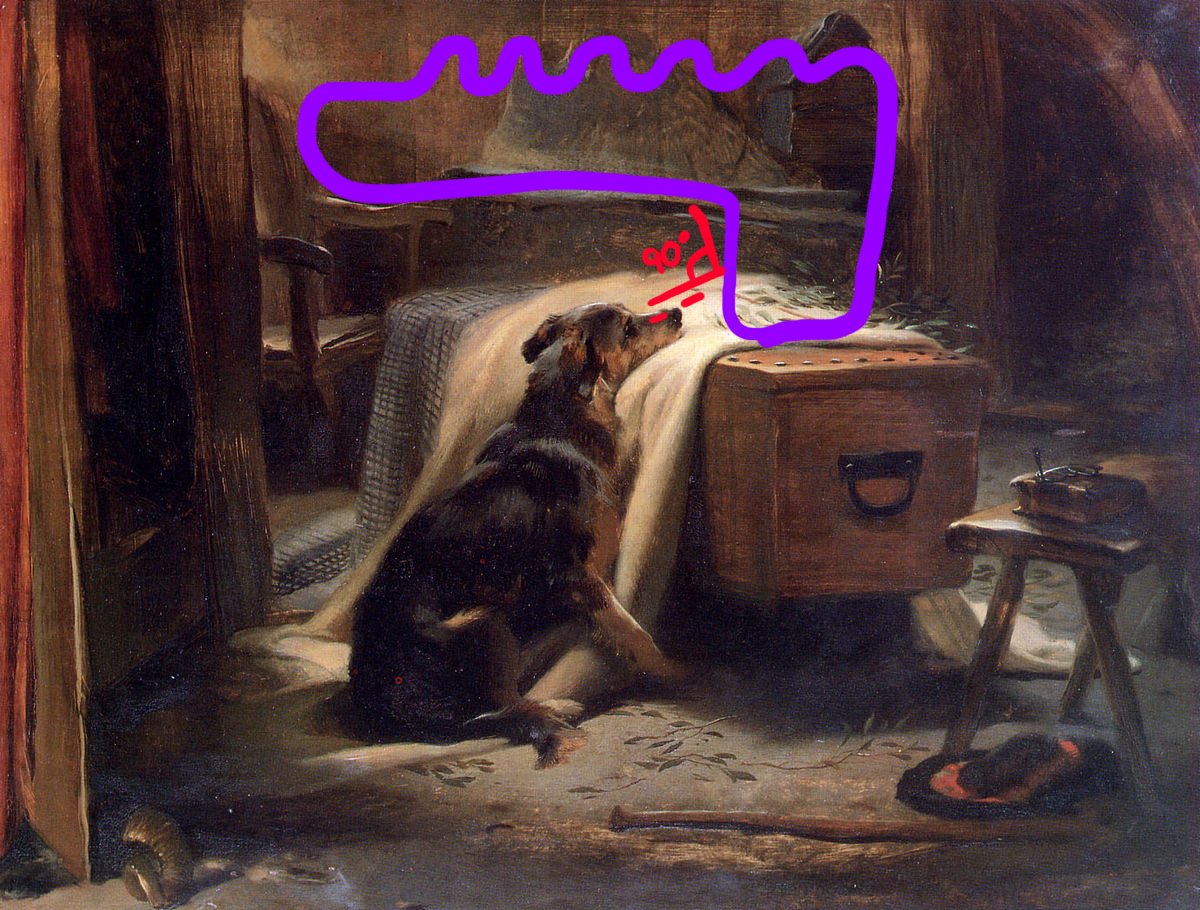

(Below, Gogh Pringling)

This has nothing to do with the potato chip named Pringles. Please cast them from your mind at this point if you are unfamiliar with Pringling.

(Below, Gogh Pringling)

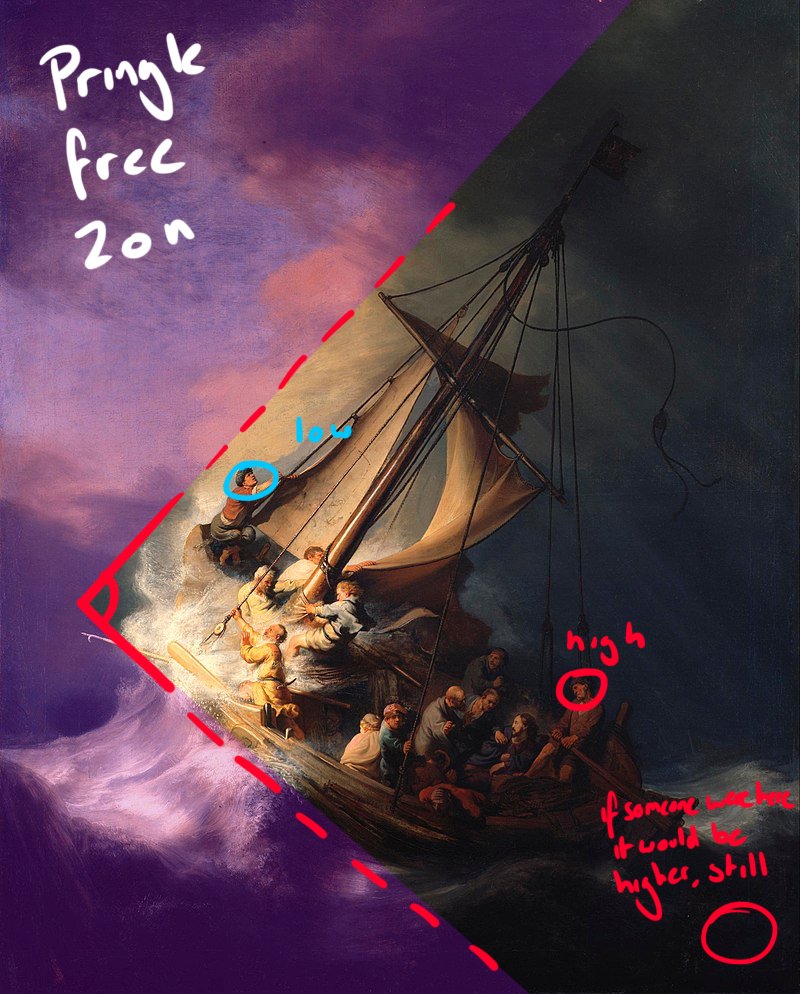

The Baroque period was rife with anti-pringling sentiment, but artists such as Rembrandt used the common right-angle rule to maintain Pringle-Free zones. As we all know, pringling is distributed based on distance from the prime angle.

There are many other rules to pringling, however; Vermeer was a master of utilising it in his work. The spiralling hair, for example, in the lacemaker, actually continues all the way down and off the canvas and onto the gallery floor.

This continued on, wherein the first examples of using pringling, and RE-pringling (That is, reframing the pringling within a context) were seen in equestrian and animal portraiture, namely by Stubbs and Landseer.

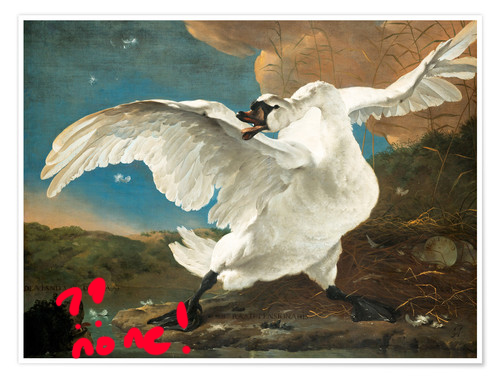

Interestingly, and this is fascinating, any painting containing a Swan, duck, or geese, by the nature of their very presence, contains NO pringling. This is a universal fact and scientists to this day are stumped as to why.

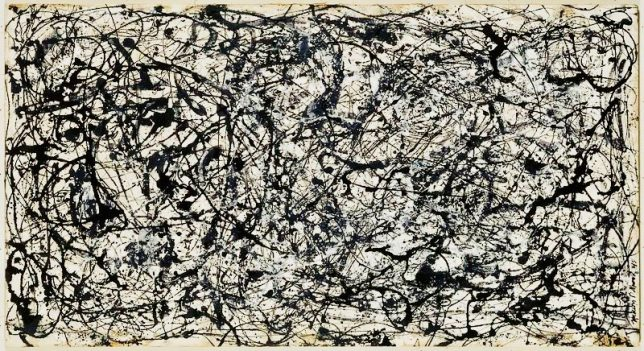

Abstract art is a hit or miss. Only one of these Pollock works features pringling. I don& #39;t think I need to point out which.

Anyway, I& #39;d love to hear your opinions on Pringling, and Repringling, and any examples you find that are noteworthy.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter