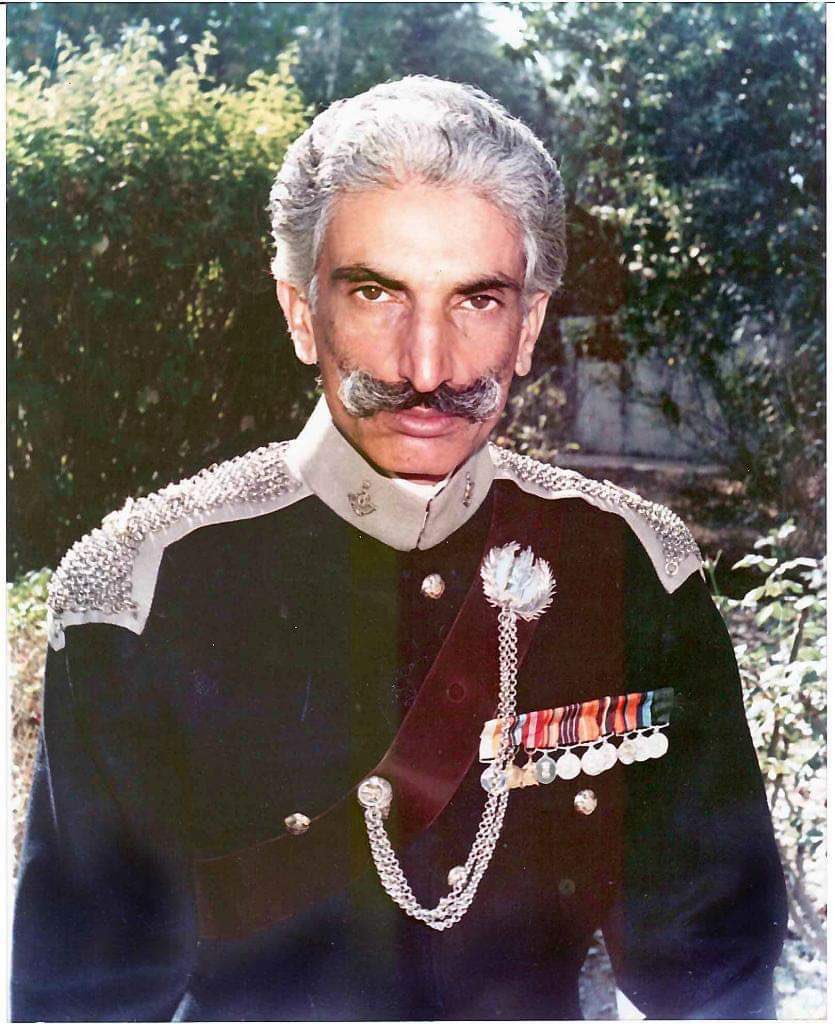

Lt Gen Hanut Singh Rathore, PVSM, MVC

If one was asked to describe Hanut Singh, in one word, the one that would fit the bill is `Soldier’. He epitomizes courage, both moral and physical, a high standard of morality, fair-mindedness, discipline, and professionalism.+

If one was asked to describe Hanut Singh, in one word, the one that would fit the bill is `Soldier’. He epitomizes courage, both moral and physical, a high standard of morality, fair-mindedness, discipline, and professionalism.+

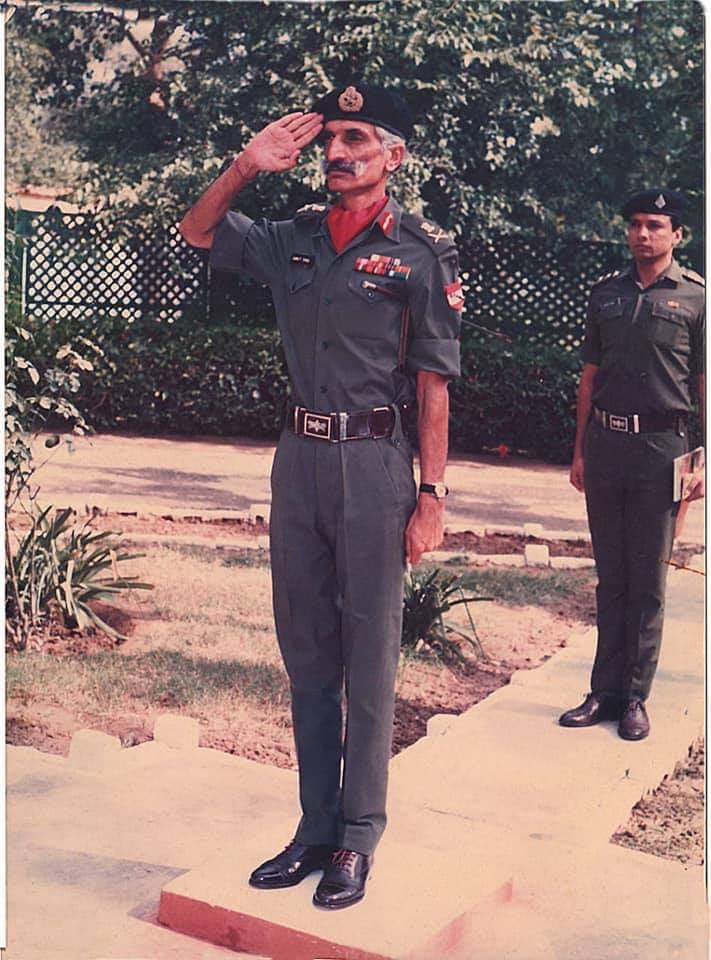

Though he did not reach the highest rank - he retired as a Lt Gen - Hanut had become a legend even as a Lt Colonel when he was commanding the most prestigious cavalry regiment in the Indian Army, 17 Horse. Also called the Poona Horse, this unit has the unique distinction of+

winning four VCs and two PVCs.

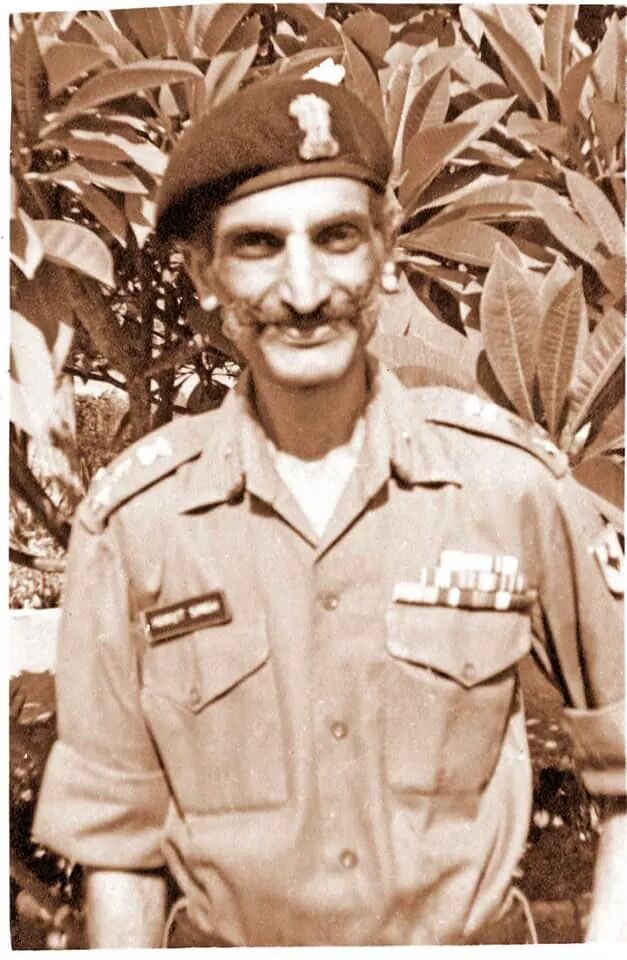

Hanut was himself decorated with the MVC, in 1971, when he was in command of the regiment. His subsequent tenures, in command of the Armoured Division, and the Strike Corps, only reinforced his claim, as the best armor commander which India has+

Hanut was himself decorated with the MVC, in 1971, when he was in command of the regiment. His subsequent tenures, in command of the Armoured Division, and the Strike Corps, only reinforced his claim, as the best armor commander which India has+

produced, and the only one the Pakistani Army feared and respected.

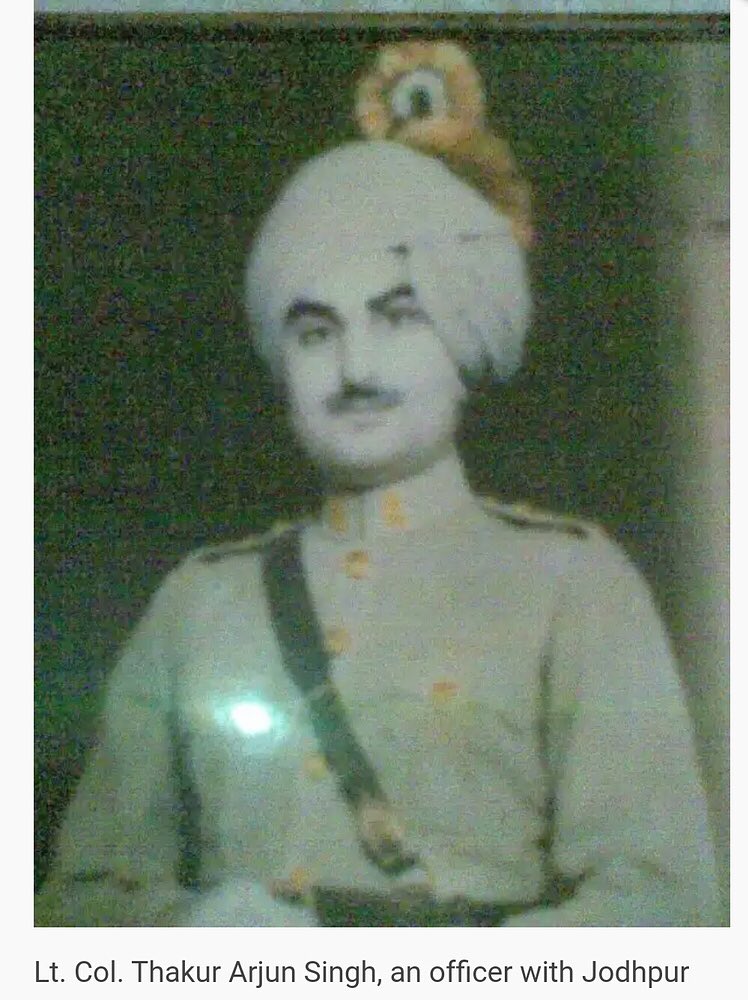

To understand Hanut, one must study his background and early life, which were instrumental in the development of his unique traits and value systems. Hanut is the scion of a proud clan of Rathore Rajputs, from+

To understand Hanut, one must study his background and early life, which were instrumental in the development of his unique traits and value systems. Hanut is the scion of a proud clan of Rathore Rajputs, from+

Jasol, in Barmer district of Rajasthan. The Jasol Rajputs are known for their valour, patriotism, courage and highly individualistic nature, born out of centuries of independent existence.

After losing Kanauj, a branch of the Rathores, under Rao Siaji, the son of Raja Jai Chand+

After losing Kanauj, a branch of the Rathores, under Rao Siaji, the son of Raja Jai Chand+

of Kanauj, established a kingdom at Khed, near Jasol. It was from here that the Rathores branched out and established the kingdoms of Jodhpur, Bikaner, Idar, and the rest. For this reason, the Rathores of Jasol consider themselves as the senior House of the Rathores.+

They have maintained their independent status ever since, defending it against all comers. Hanut’s father, Lt Colonel Arjun Singh, was himself a great soldier, who served in the Jodhpur Lancers and later commanded the famous Kachawa Horse.

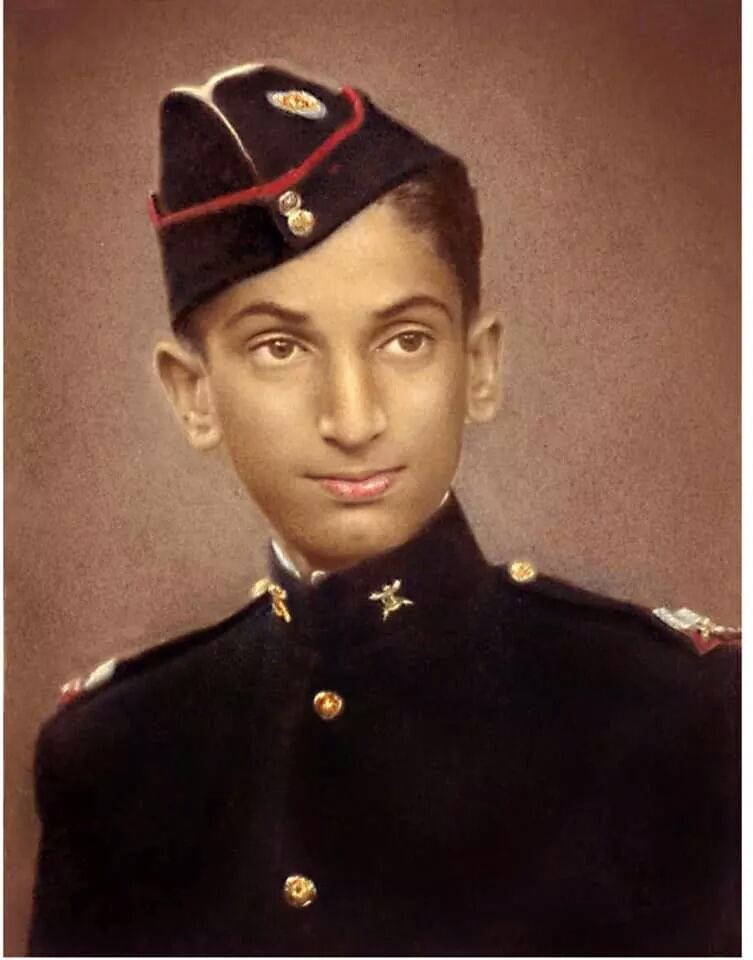

Hanut was born on 6 July 1933, at Jasol. He was sent to Colonel Brown’s School at Dehradun for his early education, where he was exposed to Western values, some of which conflicted with those in existence for centuries in Rajput society. He tried to synthesize them, by adopting+

what was best in both traditions. At school, Hanut was a brilliant student and earned a double promotion, from Class 7 to Class 9. He was a voracious reader and made an extensive study of Rajput history and tradition, in which he took immense pride. His choice of the martial+

profession was almost natural, as was his predilection for the Cavalry, which he later joined.

On 1 January 1949, the Joint Services Wing (JSW) of the IMA was established, at Clement Town, in Dehradun. This was later shifted to Khadakvasla, near Poona, and renamed the+

On 1 January 1949, the Joint Services Wing (JSW) of the IMA was established, at Clement Town, in Dehradun. This was later shifted to Khadakvasla, near Poona, and renamed the+

National Defence Academy. Hanut joined the first course at the JSW, along with S.F. Rodrigues, who later become COAS; Ram Das, who rose to be the Chief of Naval Staff, and N.C. Suri, who retired as the Chief of Air Staff. In the Academy, he was a loner, known for his strict+

personal discipline, moral values and strength of character. His colleagues could not fail to notice these qualities and held him in high regard. Unfortunately, this envy turned to jealousy, in later years, when some of his colleagues used his strong individualistic traits to+

sideline him, calling him arrogant and stubborn. Hanut was commissioned on 28 December 1952 into 17 Horse, also known as the Poona Horse, which is one of the elite cavalry regiments of the Indian Army. This was natural, given his background, and inclination. In the early 1900s,+

Maharaja Sir Pratap Singh of Jodhpur, the famous Sir ‘P’, had funded the raising of two Rathore Rajput squadrons in The Poona Horse. Sir ‘P’ was appointed Honorary Colonel of the Regiment, and since then, the Maharajas of Jodhpur have continued to hold this appointment.+

Hanut’s father and uncle, who were in the Jodhpur Lancers, did attachments with the Poona Horse. So it was only natural that Hanut should join the Poona Horse.

The Poona Horse was one the last regiments to be Indianised. As a result, there were very few Indian officers in the+

The Poona Horse was one the last regiments to be Indianised. As a result, there were very few Indian officers in the+

regiment at the time of Independence. To make up the deficiencies, several officers from other regiments were transferred. This heterogeneous collection of officers, most of whom were of average calibre, did little to enhance the reputation of the regiment. For some reason, most+

of the officers who joined after Independence, from the Indian Military Academy, were from a feudal background, and the Poona Horse came to be know as “Kunwar Sahib’s Regiment”, where the accent was on high living, rather than professionalism (In Rajasthan, the name of a high+

born Rajput is prefixed with ‘Thakur’, that of his son with ‘Kunwar’, and grandson with ‘Bhanwar’). It was only in the fifties, after a new breed of officers started being commissioned into Poona Horse, that the tide turned, and the regiment once again began to regain its lost+

glory and place of honor in the Indian cavalry.

Hanut had immense pride in his regiment, which he considered to be the best, in the Indian Army. In those days, for various reasons, it did not get the recognition it deserved, and Hanut was pained to hear certain senior officers+

Hanut had immense pride in his regiment, which he considered to be the best, in the Indian Army. In those days, for various reasons, it did not get the recognition it deserved, and Hanut was pained to hear certain senior officers+

pass uncharitable remarks about the regiment. He came to the conclusion that it was not enough for him to consider his regiment to be the best - every good regimental officer would feel the same way. It was only when the Poona Horse was acknowledged as the best by others,that it+

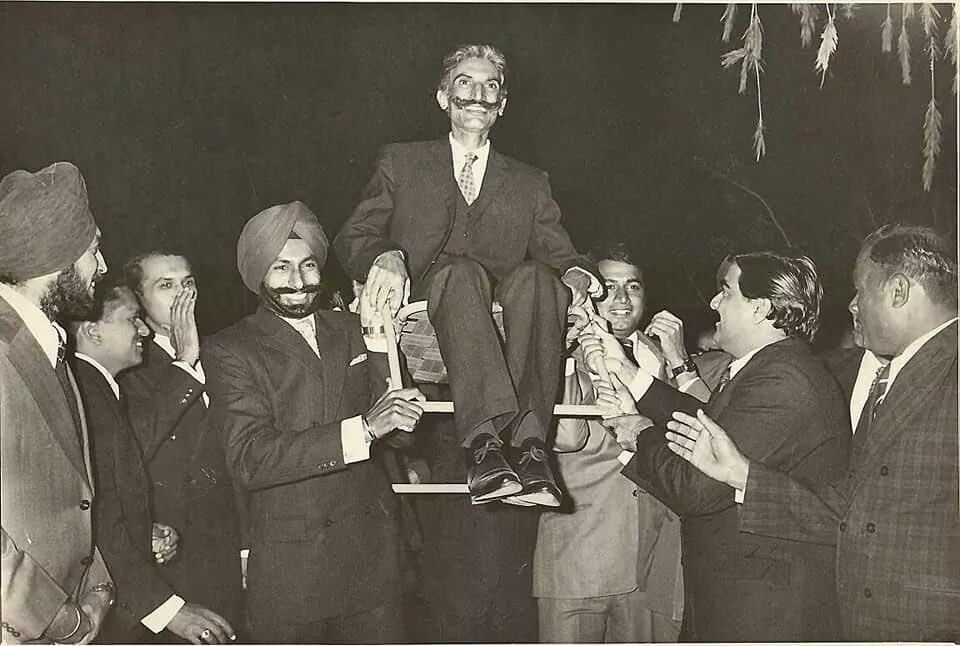

could legitimately claim this distinction. This became his self imposed mission - to get the Poona Horse accepted, and universally acclaimed, as the best cavalry regiment of the Indian Army. He worked with missionary zeal towards achieving this goal, and motivated and inspired+

other officers of the regiment to do likewise. The success of these efforts can be gauged from the fact that the exploits of the Poona Horse during the Indo Pak Wars of 1965 and 1971 became legends. It emerged as the most highly decorated regiment, in both Wars, winning a PVC in+

each. In 1965, the Commandant, Lt Colonel A.B. Tarapore was awarded the PVC; in 1971, the youngest officer in the unit, Second Lt Arun Khetarpal got the coveted award. This is a unique distinction, unmatched by any other unit in the Indian Army. To top it all, the Pak Army+

acknowledged the regiment’s valour on the battlefield by conferring on it the title ‘Fakhr-e-Hind’ (Pride of India). Hanut’s pride and faith in his regiment was vindicated.+

As a young officer, Hanut developed a deep admiration for the German General Staff, particularly their total dedication to the profession of arms, and their unmatched expertise in the art of war. He sought to emulate these qualities himself, and motivated other officers in the+

regiment to do the same. As a result, qualities like professionalism, personal rectitude and a total dedication to the regiment and the service became the distinctive hallmark of officers of the Poona Horse and continues to be so even today. In fact, a group of officers in the+

regiment jokingly referred to themselves as the ‘PH General Staff’, and being admitted to this group was a coveted distinction, for the others. A whole generation of Poona Horse officers was directly influenced by Hanut’s ideas and views, and it is interesting to note that+

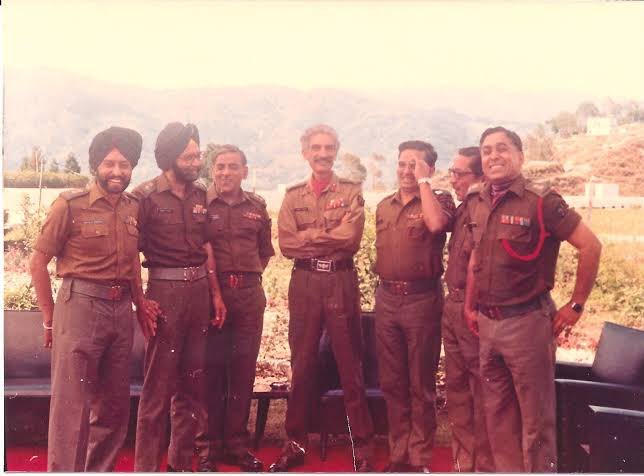

almost all of them rose to become General officers - just one more of the many unique distinctions earned by the regiment. Many of them, such as Ajai Singh, Surrinder Singh, Amrik Virk, Neville Foley, and Moti Dar, who joined the regiment after Hanut, recall with nostalgia the+

days spent under his tutelage.

Describing his first meeting with Hanut, in July 1956, Lieut General Ajai Singh has written, in the book ‘Fakhr-e-Hind - The Story of the Poona Horse’:

"It was after two to three days of my stay in the Regiment that I met him. I was sitting in+

Describing his first meeting with Hanut, in July 1956, Lieut General Ajai Singh has written, in the book ‘Fakhr-e-Hind - The Story of the Poona Horse’:

"It was after two to three days of my stay in the Regiment that I met him. I was sitting in+

the C Squadron office after the Maintenance Parade when a tall, thin, smartly turned out officer entered the office. What struck me most about him was his prominent hooked nose and very proud and penetrating look in his eyes. He walked to me and met with such enthusiasm, warmth,+

and affection that I felt as though we had known each other for ages…Thereafter, without further ado, he took me to the Squadron and introduced me to all members of his troop, which I was to take over. Having done this at the garages itself, he gave me a programme for my+

training which I was to commence from the next day; he also gave me a large bundle of books and precis which I was to read in my own time. I went through all this business-like activity in a state of total shock because, till then, such a serious approach to professional+

matters had neither been seen or heard during the few days I had spent in the Regiment. So this was Hanut - stoic, business-like and upright. Being a senior subaltern he had full authority over the Young Officers (YOs) which he exercised with ruthless impartiality, whether it+

was in the Officers’ Mess, or on the playgrounds. Some of the senior YOs, of course, resented this attitude but Hanut would not compromise. Irrespective of what the juniors and seniors felt about this remarkable man, one thing was universally true; he was loved by the men and+

admired and respected by all officers. Even then, as a youngster, I could foresee that he might just be the right man to usher in a new era in the Poona Horse -an era of regenerated Regimental spirit, professionalism, and high spirits. As time passed, my anticipation proved+

more than correct. His influence on all the officers that were to follow was so complete that some of them went so far as to emulate him even in talk, gestures, and mannerisms. This also explains why, in the course of time, he came to be nicknamed ‘Gurudev’ (teacher, or master)."

Writing in a similar vein in the same book, Lieut General Surrinder Singh, who joined the Poona Horse in January 1958, reminisces:

Amongst this lot, the officer who was to have the most profound influence was Hanut Singh, who had joined the Regiment in January 1953.+

Amongst this lot, the officer who was to have the most profound influence was Hanut Singh, who had joined the Regiment in January 1953.+

A tall, lean and ascetic figure, uncompromising in his beliefs and convictions yet gentle and considerate to his juniors and subordinates, possessed with an exuberant sense of humour and pungent, ready wit, he was an extremely dedicated and devoted professional. His forte was+

instruction, delivered in a modulated and compelling tone which carried conviction and understanding. A man of sterling character combined with a forceful personality, he had no time for fools - a fact which was soon apparent to those in this category.

An amusing sidelight was Hanut’s bachelorhood. He was strongly of the view that a married officer could not devote himself wholeheartedly to his profession, as his family would demand some of his time and attention. He remained a bachelor himself, and also encouraged others to+

follow his example. As a result, the Poona Horse had a fair number of rather senior bachelors. This added great zest to mess life but also caused considerable anxiety and consternation to the concerned parents, who naturally blamed Hanut for the continued refusal of their sons+

to enter into matrimony. Hanut devoted his spare time to spiritual pursuits, and to his favourite hobby of reading. He had an abiding love for books, and read extensively on a wide variety of subjects. But what he loved to read was spiritual literature, and the biographies of+

great men, particularly the great Captains of War. He found socializing, and the meaningless small talk that goes with it, painfully boring. He liked nothing better than to be left alone, with a good book. In an extroverted society like the Army, this character trait of his was+

considered odd, and he was soon dubbed as being anti-social. Hanut did not mind this and was quite happy as long as he was left to himself, and his books.

In the mid-fifties, the Poona Horse was issued with Centurion tanks. Hanut, who was then a young Captain, was selected to+

In the mid-fifties, the Poona Horse was issued with Centurion tanks. Hanut, who was then a young Captain, was selected to+

attend a Centurion tank gunnery course, in the United Kingdom, in 1958. He was awarded a ‘Distinction’ on this course, and on his return, was appointed a gunnery instructor at the Armoured Corps Centre and School, Ahmednagar, in May 1959. There he rewrote the General Staff+

pamphlet on ‘Technique of Shooting from Armoured Fighting Vehicles’. He also introduced revised techniques of shooting, and new tank gunnery training methods, and wrote out precis for disseminating instructions on these subjects. These continued to be the bedrock of gunnery+

training in the Armoured Corps, as long as the Centurions were in service; and it was these techniques, and training methods, which enabled the Centurions to outshoot the Pakistani Pattons, & establish their supremacy on the battlefield, during the Indo Pak wars of 1965 and 1971.

When Hanut joined the Armoured Corps, there was no tactical doctrine available on armour, and neither were there any publications on armour tactics at the unit level. What was taught at the Armoured Corps Centre and School was basically Infantry oriented tactics, based on precis+

issued by the Infantry School, Mhow. Hanut felt that armour must have a tactical doctrine of its own, based on the principles of mobile warfare. So he decided to evolve such a doctrine, and based on that, develop unit-level tactics, for armoured troops, squadrons, and regiments.+

In this context, he was of the view that only the Germans had really understood mobile warfare and practiced it during the war. He carried out a deep study of the campaigns and battles fought by the Panzer formations and units during World War II, in order to grasp the basic+

principles of mobile warfare. Based on these, he began developing unit-level tactics, which he would teach, and practice in his troop and squadron during training. From the experience gained, he would modify and expand them, and disseminate them to other officers in the regiment+

He kept detailed notes, which were constantly updated, over the years.

In December 1960, Hanut returned to the regiment. After attending the Junior Command Course at the Infantry School in 1961, he began preparations for the Staff College entrance examination.+

In December 1960, Hanut returned to the regiment. After attending the Junior Command Course at the Infantry School in 1961, he began preparations for the Staff College entrance examination.+

He qualified, and proceeded to Wellington, to attend the course in 1963. His colleagues on the course remember him as a thoroughly dedicated professional, who had little time for distractions such as the races at Ooty, or the weekly dances at the Gymkhana Club. Even as a+

student, his leadership qualities became abundantly clear, to his instructors, as well as his colleagues.

There is an interesting anecdote about Wellington, which brings out Hanut’s character, and style. During the telephone battle, he was given the appointment of a divisional+

There is an interesting anecdote about Wellington, which brings out Hanut’s character, and style. During the telephone battle, he was given the appointment of a divisional+

commander. As is the custom, he was wearing the badges of rank of a Major General, though he was actually a Major. This was done to give realism, during training. After he had given out his orders, the actual ‘battle’ commenced. At about 9 p.m., after the ‘enemy’ had made his+

opening moves, Hanut told his staff that he was retiring for the night, and was not to be disturbed until a situation arose which required his decision, or personal intervention. This caused some surprise since it was contrary to the normally accepted, nail chewing image of a+

GOC, supposedly under pressure, who remained on tenterhooks and kept harassing his staff and subordinates, instead of letting them alone to get on with their jobs. The result was that by the time he was actually required to do something, he was already bleary-eyed, and his mind+

fogged for want of rest and sleep.

Having said so, Hanut went to his allotted office and went to bed on the camp cot, which he had placed there. He slept soundly and awoke the next morning to the twittering of birds. It seemed strangely quiet, so he went out to find out what+

Having said so, Hanut went to his allotted office and went to bed on the camp cot, which he had placed there. He slept soundly and awoke the next morning to the twittering of birds. It seemed strangely quiet, so he went out to find out what+

was going on. He found all the rooms locked, and no sign of the other student officers, or directing staff. He later learnt that as the ‘enemy’ had failed to make any headway, the exercise had been prematurely called off at 1 a.m. The senior instructor told the others to go+

home, without disturbing Hanut, in accordance with the instructions he had given to his staff! This incident became the subject of much-amused comment, during the summing up, and even later. Hanut performed exceptionally well on the course, and when it was over, he was posted as+

Brigade Major of 66 Infantry Brigade. During the 1965 War, when Poona Horse wrote its name into history books, by destroying 60 enemy tanks for the loss of only nine of its own, and Lieut Colonel Tarapore won a posthumous PVC, Hanut was not with the regiment. After a tenure of+

a little over two years in this appointment, he was reverted to his regiment, in October 1966. After spending two years with the regiment, Hanut was again posted to a prestigious staff appointment, as GSO 2, in the MO Directorate at Army HQ. This was the first of his many stints+

in MO, where he was to serve again as a Brigadier and as a Major General.

In August 1970, Hanut was promoted to Lieut Colonel and posted as Officer Commanding Tactical Wing in the Armoured Corps Centre and School. Hanut had retained his notes, made during his earlier tenures+

In August 1970, Hanut was promoted to Lieut Colonel and posted as Officer Commanding Tactical Wing in the Armoured Corps Centre and School. Hanut had retained his notes, made during his earlier tenures+

at the School, and which he had updated periodically, during his subsequent tenures in the regiment, and on staff. He used his notes to write out the basic books on armour tactics, and on the tactical handling of armoured units and subunits. +

These remain the basic books on armour tactics even today and are still used at the Armoured Corps Centre and School and the College of Combat. In April 1971, he was nominated on the Senior Command course at the College of Combat, which had recently been established at Mhow.+

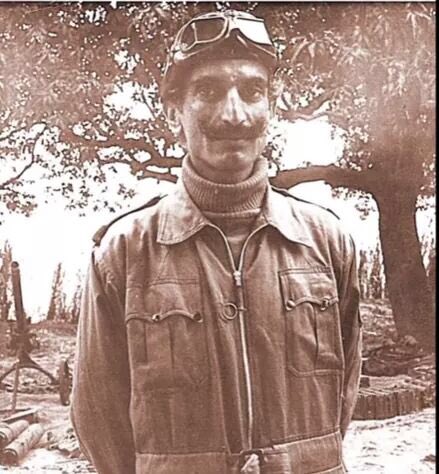

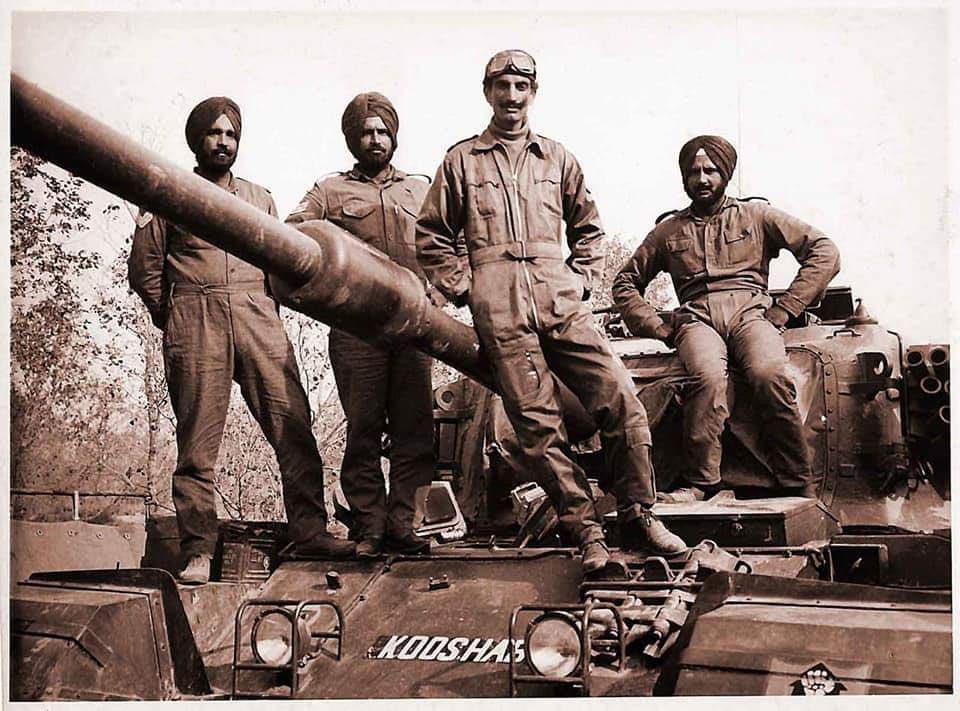

In September, 1971, Hanut was posted as Commandant, 17 Horse. (The Commanding Officer, or CO, is called the Commandant, in cavalry regiments). The regiment was located at Sangrur, and was part of 16 Independent Armoured Brigade, which was then commanded by Brigadier A.S. Vaidya,+

MVC, who later became Chief of Army Staff. By then, war clouds had begun gathering, and within days of his assuming command, Hanut had to move his regiment to battle locations. 17 Horse was carrying out its annual field firing at Naraingarh ranges on 8 October 1965, when it+

received a message asking it to return at once to its permanent location. On his way back to Sangrur, Hanut reported to HQ 16 Independent Armoured Brigade, where he was briefed by the Brigade Commander. Vaidya informed him that 17 Horse had been placed under command+

323 Infantry Brigade, at Dinanagar, and he should move the regiment to its concentration area immediately. The regiment began moving by road and rail on 10 October, and within four days, had concentrated at Sujanpur, a small village near Madhopur. After reaching its new+

location, Hanut was called to HQ 39 Infantry Division, and briefed regarding his task. Hanut learned that his regiment had been temporarily placed under command 323 Infantry Brigade, for a defensive task. There were reports of an impending attack by Pakistan in the general area+

Gurdaspur-Dinanagr, and 323 Infantry Brigade was deployed to contain this thrust, with 17 Horse in a supporting role. Hanut was subsequently briefed by Brigadier G.S. Grewal, Commander 323 Infantry Brigade, who asked him to base himself at Dinanagar, and select suitable+

dispersal areas for his regiment. By the time Hanut reached the rest house at Dinanagar, which he had selected as his regimental HQ, it was almost 10 p.m. While Hanut was inside the rest house, he felt that some men were was following him, in the dark. +

He stopped, and asked the men, in loud voice, what they were upto. It transpired that it was a party, led by an officer, from 36 Infantry Division, who had been reconnoitering the area. Hearing the tanks of 17 Horse coming into the area, they had assumed that it was the+

spearhead of the Pak offensive. Hanut’s aquiline nose, and handlebar moustache had led them to mistake him for a Pathan. They were apologetic when they found that they had been stalking the Commandant of the Poona Horse, instead of a Pakistani officer.+

Next morning, orders were received that the Scinde Horse, which had just arrived, would relieve the Poona Horse, which was to revert under command of 39 Infantry Division, and move to Malichak. After spending almost a month there, the regiment moved to a forward concentration+

area near Dinai, just short of Samba, on the Pathankot-Jammu road. By this time, all personnel on leave, courses and extra regimental employment had rejoined, and the regiment was upto full strength. The period spent in Malichak had been put to good use, in training, and+

reconnaissance.

In 1971, the Indian Army’s main task was the liberation of Bangla Desh, then called East Pakistan. On the Western Front, it was decided that a posture of offensive defence would be maintained. This was primarily because of the commitments of troops in the East,+

In 1971, the Indian Army’s main task was the liberation of Bangla Desh, then called East Pakistan. On the Western Front, it was decided that a posture of offensive defence would be maintained. This was primarily because of the commitments of troops in the East,+

and the possibility of intervention by China. However, it was expected that Pakistan would undertake a major offensive, either in the Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, or Rajasthan. As part of his overall strategy, Lieut General K.P. Candeth, GOC-in-C, Western Command, had planned+

certain offensive operations, with the intention of drawing out Pakistani reserves, so that they were not in a position to undertake major offensives against India. An advance by 1 Corps into the Shakargarh bulge was part of these plans.

Lt General K.K. Singh, GOC 1 Corps,+

Lt General K.K. Singh, GOC 1 Corps,+

had been the DMO at Army HQ before assuming command of 1 Corps in October 1971. He was thus familiar with the overall strategy and plans, for the operations. He had three infantry divisions (36, 39 and 54), two independent armoured brigades (2 and 16), two independent artillery+

brigades and two engineer brigades. He also had a locating battery and an air observation post squadron. 36 Infantry Division, under Major General B.S. Ahluwalia, was initially deployed South East of the Ravi river, in the Thakurpur-Gurdaspur-Dinanagar area;+

39 Infantry Division, under Major General B.R. Prabhu, was North of the Ravi, in the Madhopur-Bamial-Dayalchak area; and 54 Infantry Division, under Major General W.A.G. Pinto, was deployed around Samba, between the Bein river and the Degh Nadi.+

Lt General K.K. Singh, known as ‘KK’, had commanded 1 Armoured Brigade during the 1965 war, and Poona Horse had been under his command at that time. In 1971, he was given the task of containing the enemy offensive, and then delivering a riposte against his lines of+

communication, so as to force him back. In case the enemy did not launch an offensive, ‘KK’ was to advance into the Shakargarh bulge east of the Degh Nadi, and capture Zafarwal, Dhamtal and Narowal. Subsequently, he was to secure the line Marala-Ravi link canal-Degh Nadi and+

later take Pasrur. ‘KK’ appreciated that the best manner of carrying out the tasks allotted to him was to go on the offensive. He planned to launch the offensive in the central sector of the Corps zone, retaining a strong defensive posture on the flanks. As part of this plan,+

54 Infantry Division was to advance between the Degh Nadi and the Karir Nadi, led by 16 independent Armoured Brigade less 16 Cavalry. 39 Infantry Division was to advance beteween the Bien river and the Karir Nadi, led by 2 Independent Armoured Brigade, to guard the western flank+

The eastern flank was to be guarded by two brigades (one each from 26 and 39 Infantry Divisions), supported by 16 Cavalry. 36 Infantry Division, supported by Scinde Horse, was to hold a defensive position along the Ravi river. +

Based on the information available at that time, it had been appreciated that the enemy would have laid three or four tiers of minefields, starting from the internatioanl border. In 54 Infantry Division sector, the first minefield was visualized to be at the border; the+

second along the general line Bhoi Brahma-Thakardwara-Nagwal; the third along the general line Ghamrola-Barkhanian; and the fourth in conjunction with the Basantar Nala. The enemy was also expected to have advanced positions based on the Basantar Nala, with covering troops+

operating ahead of it, to delay the advance of Indian troops, and deny crossings over the minefields. Based on the enemy’s anticipated deployment, it was planned that two infantry brigades ex 54 Infantry Division, with a squadron each of 17 Horse under command, would secure a+

bridgehead across the first minefield in area Dandaut-Gola-Mawa-Mukhwal and establish a firm base for the divisional advance. The third brigade of 54 Infantry Division and 4 Horse would then advance between the Basantar river and Karir Nadi, with a view to secure crossings+

across the second minefied at Thakurdwara. Thereafter 4 Horse with one brigade would make another bridgehead across the third minefield at Barkhanian. Once the third minefield had been breached, a combat group comprising 17 Horse and 18 Rajputana Rifles less two companies would+

break out and secure an encounter crossing over the Basantar Nala in general area Pinjori, for a subsequent advance for the capture of the Zafarwal-Dhamtal complex. While the various contingencies were being worked out, Hanut was dismayed to find that in each one of these plans,+

his regiment was kept in reserve, and not given an operational task. When this happened the third time running, Hanut met the Brigade Commander and asked him why his regiment was not being given any task. “From this,” said Hanut, “I can only conclude that you do not have +

confidence in me, or in my regiment, or both.” Vaidya was initially non-plussed, at being confronted in this manner by one of his COs, but had to agree that he was right. He went on to explain that he had just taken over the brigade and did not know the units well enough.+

He was going by what his predecessor, Brigadier K.K. Kaul had told him about the units, and their COs. Hanut pointed out that because of a personality clash between Lt Col Shiv Raj Singh, the previous Commandant of 17 Horse, and the Brigade Commander, the latter’s opinion about +

the regiment was biased, and requested him not to go by it. Vaidya agreed and assured Hanut that in future, he would see that his regiment got its rightful due.

After airstrikes against Indian airfields during the evening of 3 December 1971, Pakistan attacked Indian positions+

After airstrikes against Indian airfields during the evening of 3 December 1971, Pakistan attacked Indian positions+

in Chhamb the same night, preceded by heavy artillery bombardment of border outposts. The next day, Yahya Khan formally declared war. Indian counter offensive plans were immediately put into motion, in the Eastern as well as the Western sectors. In the evening, on 4 December,+

17 Horse received orders to deploy for the protection of the firm base of 54 Infantry Division. This entailed move of the regiment from East to West across the Samba T junction. Simultaneously, 7 Cavalry was asked to move from West to East across the same choke point, to its+

forward assembly area West of Samba. The two columns reached the choke point at the same time and got stuck in a traffic jam. Fortunately, the enemy artillery and air did not take advantage of the disaster, and the chaos was sorted out only after the two COs personally+

intervened. It was primarily the initiative of the junior leaders of both regiments, who worked overtime to disentangle their respective tanks, which enabled the regiments to reach their forward assembly areas by first light.

At the border post of Galar Tanda, there was a+

At the border post of Galar Tanda, there was a+

30 foot high observation tower, which provided the Pakistanis observation into Indian territory, & could be used to bring down artillery fire over the concentration areas of own troops. B Squadron was located at Gala,right opposite the tower, and Hanut ordered them to destroy it+

An accurate shot from one of the tanks of B squadron brought down the tower, and this signalled the start of the battle, in the 54 Infantry Division sector. A troop of Pakistani tanks, hidden behind the tall grass, emerged on hearing the shot, and pulled back in panic.+

Hanut realised that since the enemy tanks were moving freely along the border, there could not be a minefield in that area. He conveyed this information to Commander 16 Armoured Brigade, but Vaidya did not react. The full scale attacks went ahead as planned.+

91 and 74 Infantry Brigades launched their attacks for the capture of Dandout-Chamana Khurd-Chhahal and Mukhwal at 2000 hours on 5 December. The infantry did not encounter any enemy, and neither did the trawls find any mines, when they went through the anticipated minefield.+

Both brigades secured their bridgeheads, and two squadrons of 17 Horse were moved to protect their flanks. Shortly after midnight, 4 Horse was inducted into the bridgehead, but commenced its break out only at first light. By 0800 hours, leading elements of 4 Horse had contacted+

the minefield astride Thakurdwara. Surprisingly, the regiment waited till last light, before the leading squadron commenced breaching the minefield. Once again, no enemy was encountered, and a firm base was secured across the minefield. A squadron of 17 Horse was moved up, to+

take over the firm base, and relieve 4 Horse for further advance.

Unknown to Indian troops, Pakistani armour was present in the area. B Squadron of Pak 20 Lancers had withdrawn behind the first defensive minefield at Thakurdwara on the night of 5/6 December, and next day, when+

Unknown to Indian troops, Pakistani armour was present in the area. B Squadron of Pak 20 Lancers had withdrawn behind the first defensive minefield at Thakurdwara on the night of 5/6 December, and next day, when+

4 Horse was advancing, this squadron was strafed by the Indian Air Force, and withdrew to the next minefield, at Barkaniyan, by last light on 6 December. It was joined by a squadron of 33 Cavalry (Pattons), and soon afterwards, the rest of 20 Lancers had also concentrated+

behind the second minefield. On the morning of 7 December, 17 Horse was moved from Bhoi Brahmana to guard the western flank. To the East, the operations of 39 Infantry Division, with 7 Cavalry in support, had not made much progress, and were still to cross the first minefield.+

The enemy had developed Dehlra and Chakra as a strong defensive position, and a squadron ex Poona Horse was sent to Dadwan Kalan to mask Chakra, and secure Bari, while 4 Horse was orderd to clear Darman and Ghamrola. After completing its task, 4 Horse moved forward to+

Barkaniyan, and Poona Horse less two squadrons was moved from Rayian to Gala, with the other two squadrons at Bhoi Brahmana and Sadwal/Dadwan Kalan.

On the afternoon of 8 December, information was received of a likely enemy counter attack at Mukhwal. 17 Horse less two+

On the afternoon of 8 December, information was received of a likely enemy counter attack at Mukhwal. 17 Horse less two+

squadrons, with a company of 18 Rajputana Rifles under command, was ordered to secure Mukhwal. As the column was moving along a high embankment, it came under air attack. Only the leading tanks could get off the road, while the rest of the two-kilometer long column continued to+

move in single file along the narrow road. Hanut was in the leading tank and had managed to get off the road, into the tall elephant grass. However, he saw sortie after sortie of enemy aircraft coming in to attack the column with bombs and rockets.+

Expecting most of his tanks to have been written off, he was very perturbed, and when the attack was over, he asked all stations to report casualties. Everyone was surprised, and relieved, when it was found that there were no casualties. Having seen their bad shooting, the+

Poona Horse treated the Pakistani Air Force with contempt, for the rest of the war.

After reaching Mukhwal, Hanut deployed the company of 18 Rajputana Rifles on the high ground ahead of the village, with their armoured personnel carriers (APCs) in close support.+

After reaching Mukhwal, Hanut deployed the company of 18 Rajputana Rifles on the high ground ahead of the village, with their armoured personnel carriers (APCs) in close support.+

The armour was held in reserve, hidden from view in the village itself. The plan was that when the enemy launched his attack, the infantry would mount their APCs and withdraw towards Mukhwal, firing their machine guns. Once the enemy assumed that he had captured the area and+

began to reorganise, the tanks and APCs would mount a combined assault. Shortly after the deployment had been completed, the enemy started shelling the area, and Hanut thought that he was registering targets before the attack was launched. However, the infantry and armour+

waited in vain, as the enemy did not attack, causing all round disappointment.

While the operations of 54 Infantry Division had progressed well, 39 Infantry Division had not been able to capture Dehlra. Major General W.A.G. Pinto, GOC 54 Infantry Division, realised that unless+

While the operations of 54 Infantry Division had progressed well, 39 Infantry Division had not been able to capture Dehlra. Major General W.A.G. Pinto, GOC 54 Infantry Division, realised that unless+

the Dehlra- Chakra complex was cleared, he would not be able to progress his own operations. He therefore decided to clear it using his own troops, and gave the task to Brigadier Ujagar Singh, Commander 74 Infantry Brigade, who was given a squadron ex 4 Horse for this purpose.+

This was completed by first light on 11 December. Pinto now ordered Brigadier A. Handoo, Commander 91 Infantry Brigade, to establish a bridgehead across the Barkhaniyan minefield. 17 Horse was placed under command 91 Infantry Brigade for this operation, with the further tasks of+

breaking out from the bridgehead, contacting the enemy positions along the Basantar nullah, and if opportunity offered, to establish an encounter crossing across the Basantar. The regiment moved forward from Mukhwal and concentrated at Tarakwal by 1400 hours on 12 December.+

18 Rajputana Rifles less two companies, mounted in APCs, was placed under command 17 Horse for the encounter crossing, in addition to an Engineeer task force, with trawl tanks and bridge layer tanks.

Hanut planed to carry out the encounter crossing during the hours of darkness,+

Hanut planed to carry out the encounter crossing during the hours of darkness,+

as soon as the bridgehead acroos the minefied had been established by 91 Infantry Brigade. However, Commander 91 Infantry Brigade did not permit this, since he was worried about his own security. Hanut knew that the Basantar would be heavily defended, and a daylight encounter+

crossing would not succeed. Finally, it was agreed that a squadron of 4 Horse would take over the defence of the bridgehead, allowing 17 Horse to break out the same night. The operation began on the night of 13 December, and 91 Infantry Brigade secured a bridgehead across the+

minefield. The Engineers began trawling, and by 2330 hours, a safe lane for tanks had been cleared. At 0230 hours, the combat group commenced the break out.

After going some distance, some tank tracks were found. It was conjectured that these belonged to enemy tanks which had+

After going some distance, some tank tracks were found. It was conjectured that these belonged to enemy tanks which had+

withdrawn from the Barkhaniyan minefied, and would lead to a suitable crossing place over the Basantar. The regiment had made an elaborate navigation plan, with night charts, showing the route from point to point, and compass bearings. It was felt that following the tracks would+

result in faster movement, and save time. So the navigation plan was abandoned, and the combat group began to follow the tank tracks. This proved to be a mistake, since the enemy tanks, instead of crossing the Basantar, had veered off East, and crossed a tributary of the+

Basantar, instead of the main nullah. The ‘nullah’ was contacted in the early hours of 14 December. The crossing was found to be unmined and undefended, and only then did it dawn on the two COs that they had hit a tributary, rather than the main Basantar nullah. The combat group+

quickly swung round, to get back on the original axis, but it was soon daylight, and the area was found to be boggy. The tanks were dispersed, and it was decided to make an attempt later. As it turned out, the Basantar was heavily defended, and too formidable to have been+

breached by an encounter crossing, so the failure to reach the correct place was really a blessing in disguise. Though the regiment suffered a number of casualties due to air attacks during the day, these were not as large as what would have been inflicted if the encounter+

crossing had been attempted.

During the next two days the enemy resistance on the home side of the obstacle was systematically cleared, and on 15 December, a deliberate operation was launched, across the Basantar nullah. 47 Infantry Brigade, under Brigadier A.P. Bhardwaj, was+

During the next two days the enemy resistance on the home side of the obstacle was systematically cleared, and on 15 December, a deliberate operation was launched, across the Basantar nullah. 47 Infantry Brigade, under Brigadier A.P. Bhardwaj, was+

made responsible for securing a bridge head. The brigade had three battalions: 13 Grenadiers, 6 Madras and 16 Madras, in addition to 17 Horse nad 18 Rajputana Rifles less two companies. The plan involved the capture of area 2r in the Ghazipur reserved forest, including+

Saraj Chak by 16 Madras in Phase 1, followed by the capture of Jarpal and Lohal by 13 Grenadiers in Phase 2. 17 Horse and 18 Rajputana Rifles less two companies was to ensure protection of the bridge head against enemy counter attack. On the subsequent day, 13 Grenadiers,+

supported by a squadron of 17 Horse, was to capture Barapind, while 16 Madras, supported by another squadron of the regiment, was to capture Ghazipur.

The infantry attack went in as planned, and the bridge head was secured by 16 Madras at 2030 hous. Breaching of the minefield+

The infantry attack went in as planned, and the bridge head was secured by 16 Madras at 2030 hous. Breaching of the minefield+

commenced, and the armour was waiting, for safe lanes to be cleared. The second phase of the brigade attack also went in, and at 2330 hours 13 Grenadiers reported that it had secured Jarpal. Meanwhile, there were frantic calls from Lieut Colonel V. Ghai, CO 16 Madras, reporting+

that he was being threatened by enemy armour, building up for the counter attack. At about 0230 hours, there was another desperate appeal from Ghai, indicating that the situation was critical, and if he did not get any armour, he would not be able hold out. Hanut realised that+

waiting for the safe lanes could mean destruction of the infantry, and loss of the bridge head. Crossing the mine field, still unbreached, could result in a large number of his tanks being written off.

Hanut decided to take the risk, and send at least one squadron across, to+

Hanut decided to take the risk, and send at least one squadron across, to+

relieve the beleaguered infantry. He gave the task to ‘C’ squadron, which was led by the second-in-command, Major Ajai Singh, who had taken over after Major Moti Dar, the squadron commander, had been wounded, his tank having received a direct hit.+

Captain Ravi Deol was transferred to ‘C’ squadron from & #39;B ’ squadron, since he was familiar with the area, having seen it during daylight. The squadron began to negotiate the minefield, with Deol as the navigating officer, and Ajai in the following tank. Miraculously, the+

squadron crossed the minefield, without a single casualty, and successfully secured the bridgehead.

The next day, a jeep and an armoured personnel carrier (APC), which tried to follow the tank tracks, blew up on the enemy mines. Hanut attributes the luck of the squadron, in+

The next day, a jeep and an armoured personnel carrier (APC), which tried to follow the tank tracks, blew up on the enemy mines. Hanut attributes the luck of the squadron, in+

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter