New paper out by Andrew E. Snyder-Beattie, me, Eric Drexler and @mbbonsall about how the timing of evolutionary transitions on Earth suggests intelligent life is rare: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/ast.2019.2149">https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/...

There is life on Earth but this is not evidence for life being common in the universe! This is since observing life requires living *observers*. Even if life is very rare, the observers will all see they are on planets with life. Observation selection effects need to be handled!

Observer selection effects are annoying can produce apparently paradoxical effects such that your friends on average have more friends than you or that our existence "prevents" recent giant meteor impacts. But one can control for them with some ingenuity! https://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/W6-Observer-selection-effects.pdf">https://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk/wp-conten...

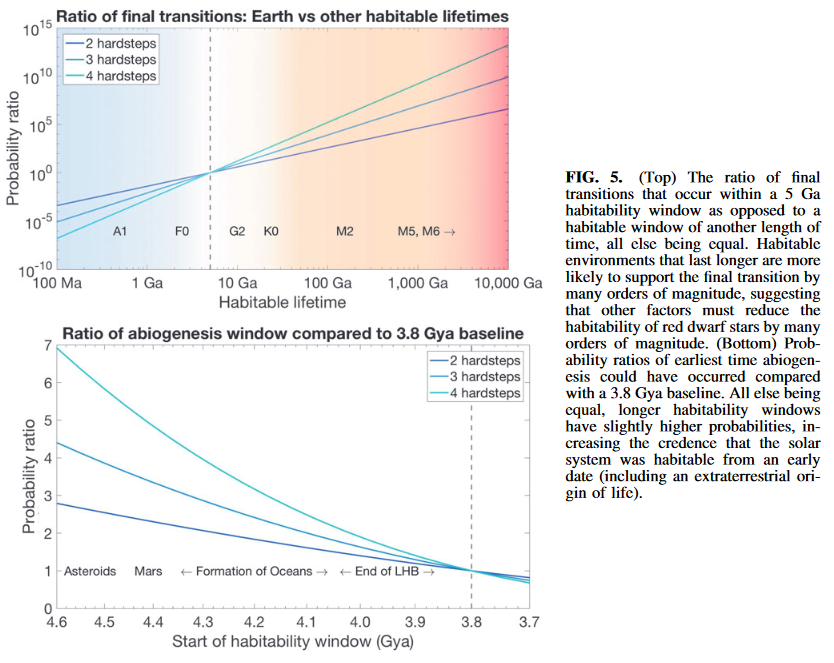

Life emerged fairly early on Earth: evidence that it is easy and common? Not so fast: if you need multiple hard steps to evolve an observer to marvel at it, then on those super-rare worlds where observers show up life statistically tend to be early.

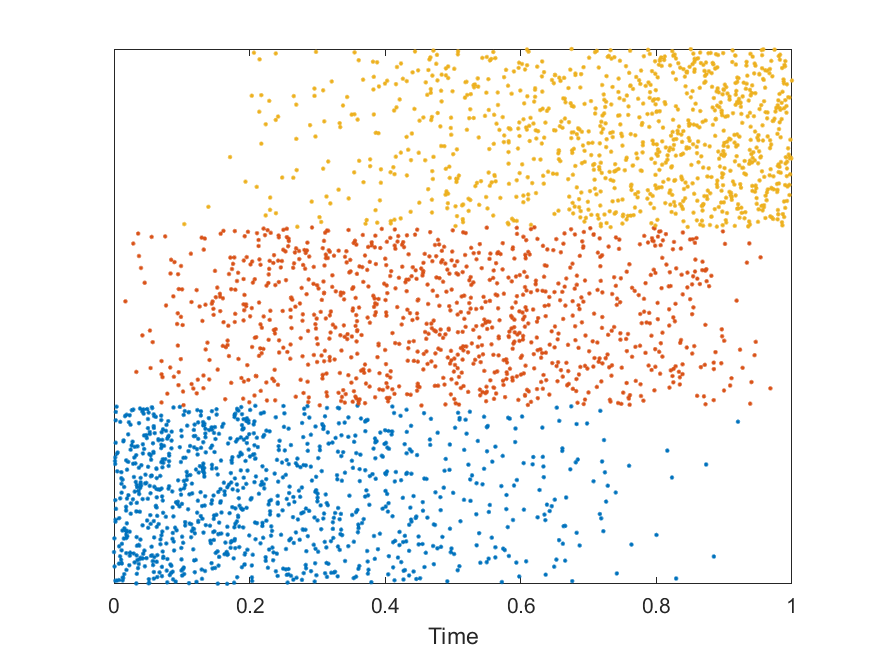

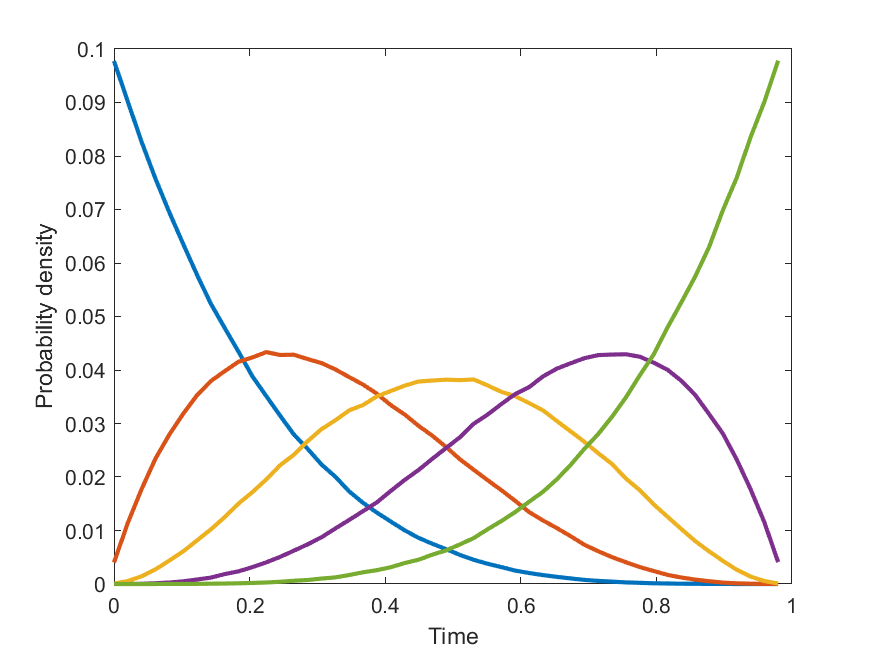

If we have N hard steps (say; life, good genetic coding, eukaryotic cells, brains, observers) as difficulty goes to infinity in cases where all steps succeed before biosphere ends they become equidistant between first and last habitability.

That means that we can take observed timings and calculate backwards to get probabilities compatible with them, controlling for observer selection bias.

Our argument builds on a chain from Carter& #39;s original argument and its extensions to Bayesian transition models. I think our main addition here is using noninformative priors.

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsta.1983.0096">https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.10... https://arxiv.org/abs/0711.1985v1 ">https://arxiv.org/abs/0711.... http://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/hardstep.pdf">https://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/... https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/109/2/395.full.pdf">https://www.pnas.org/content/p...

https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsta.1983.0096">https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.10... https://arxiv.org/abs/0711.1985v1 ">https://arxiv.org/abs/0711.... http://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/hardstep.pdf">https://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/... https://www.pnas.org/content/pnas/109/2/395.full.pdf">https://www.pnas.org/content/p...

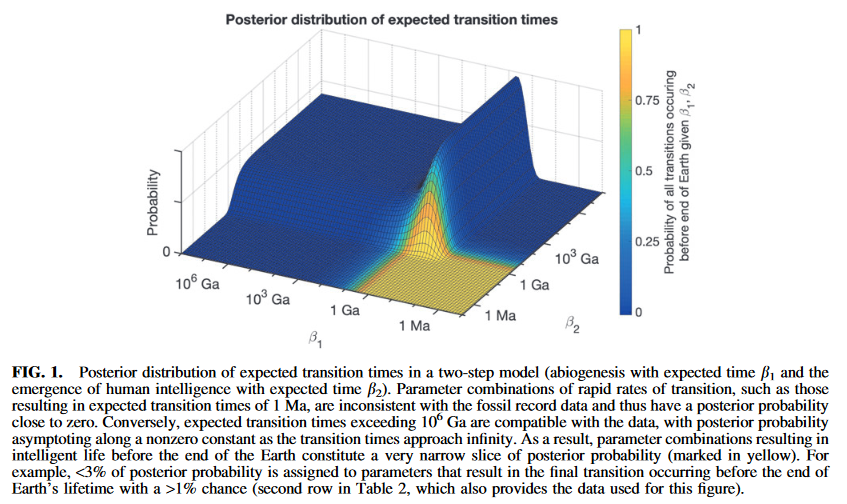

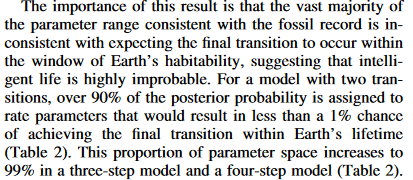

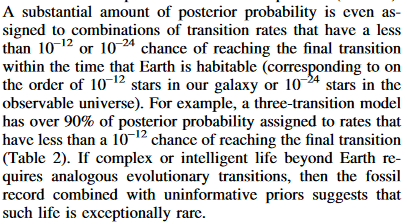

The main take-home message is that one can rule out fairly high probabilities for the transitions, while super-hard steps are compatible with observations. We get good odds on us being alone in the observable universe.

If we found a dark biosphere or life on Venus that would weaken the conclusion, similarly for big updates on when some transitions happened; we have various sensitivity checks in the paper.

Our conclusions (if they are right) are good news if you are worried about the Great Filter http://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/greatfilter.html">https://mason.gmu.edu/~rhanson/... - we have N hard filters behind us, so the empty sky is not necessarily bad news. We may be lonely but have much of the universe for ourselves.

Another cool application is that this line of reasoning really suggests that M-dwarf planets must be much less habitable than they seem: otherwise we should expect to be living around one, since they are so common compared to G2 stars.

Personally I am pretty bullish about M-dwarf planet habitability (despite those pesky superflares), but our result suggests that there may be extra effects impairing them. They need to be pretty severe too: they need to reduce habitability probability by a factor of over 10,000.

I see this paper as part of a trilogy started with our "anthropic shadows" paper https://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/anthropicshadow.pdf">https://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/an... and completed by a paper on observer selection effects in nuclear war near misses (coming, I promise!) Oh, and there is one about estimating remaining lifetime of biosphere.

The basic story is: we have a peculiar situation as observers. All observers do. But we can control a bit for this peculiarity, and use it to improve what we conclude from weak evidence, especially about risks. Strong evidence is better though, so let& #39;s try to find it!

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter