Our new paper about word-meaning priming is out now in JML! “The relationship between sentence comprehension and lexical-semantic retuning”. With @DrMattDavis @mggaskell @JenniRodd https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2020.104188">https://doi.org/10.1016/j... Here’s a thread to explain more...

Word-meaning priming shows how recent experience with an ambiguous word can change listeners’ preferred meaning minutes or hours later. Hearing “Sally worried about how crowded the BALL would be.” shifts your interpretation of ball towards the “dance party” meaning.

But when and how does this form of learning occur when someone hears an ambiguous word in a prime sentence? We tested 2 hypotheses:

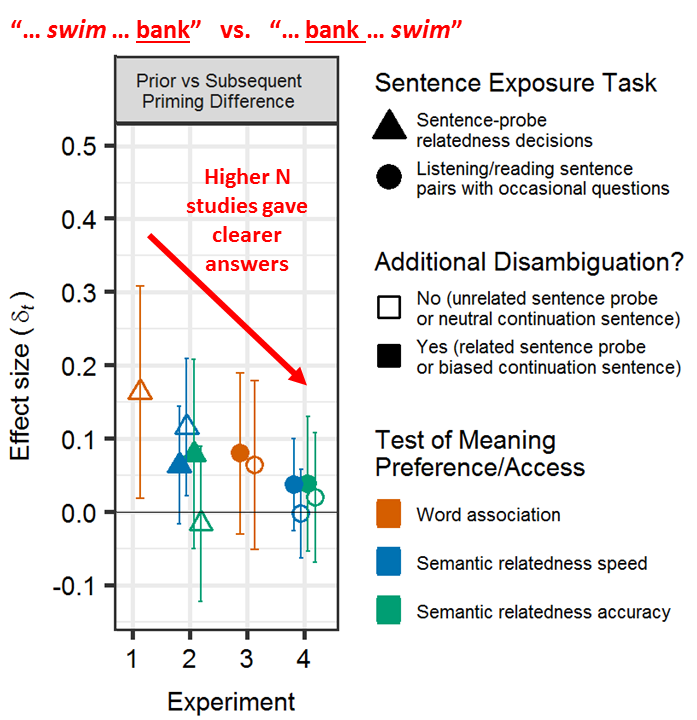

1. Learning happens during initial meaning activation/selection for the ambiguous word. So, priming should be strongest when the *context* comes before the ambiguous word (prior disambiguation, e.g. “Sally worried about how *crowded* the BALL would be.”).

Or 2. Learning happens when you correct an error and reinterpret the ambiguous word. So priming should be strongest when the word is initially misunderstood b/c critical *context* comes after (subsequent disambiguation, e.g. “Sally worried that the BALL would be too *crowded*”).

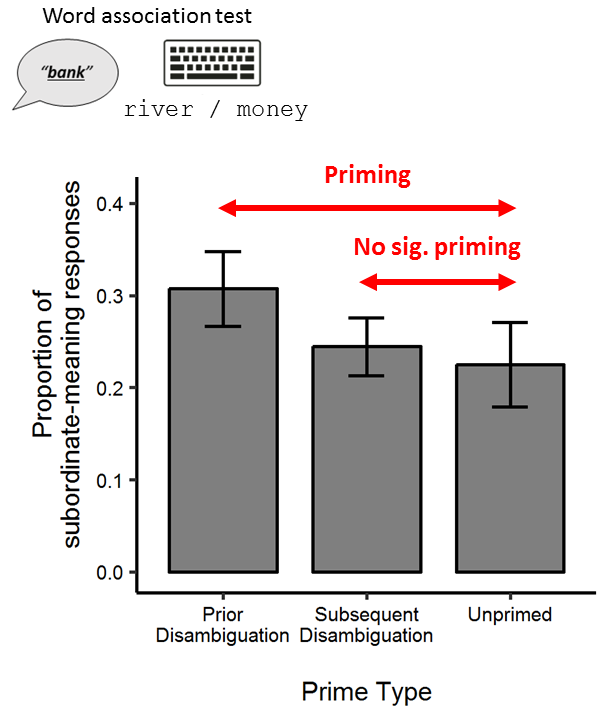

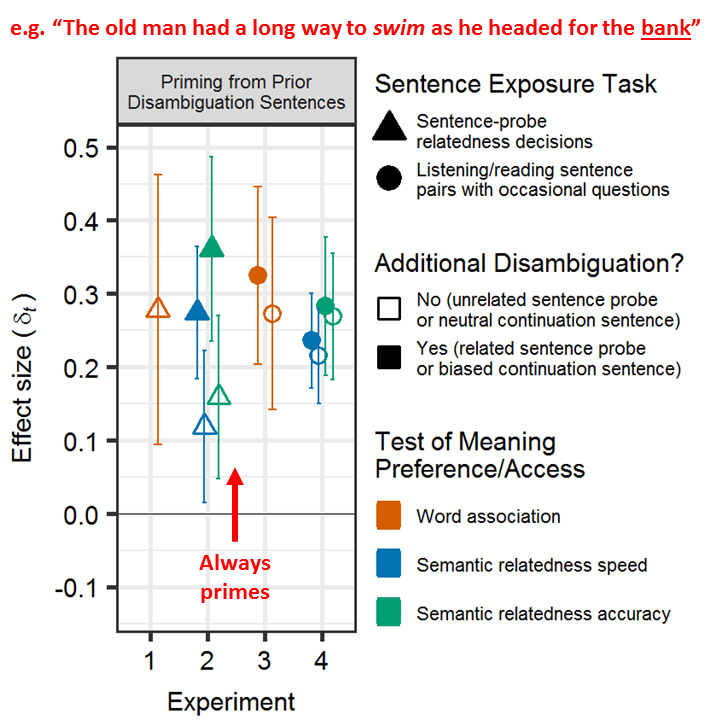

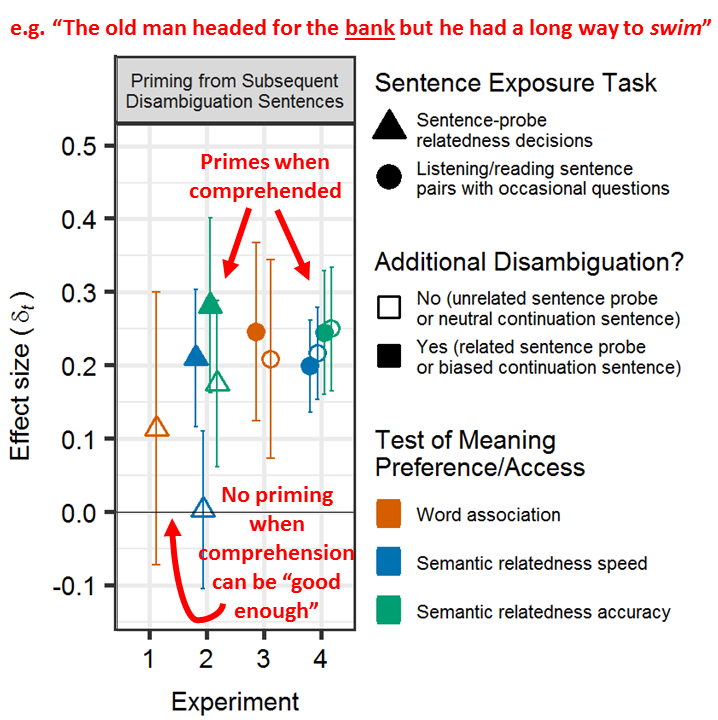

We ran 4 word-meaning priming experiments using prior and subsequent disambiguation sentences. So, which sentence type produced more priming? Well, it depends...

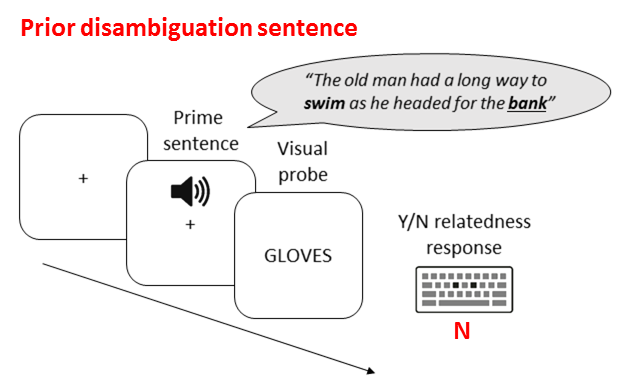

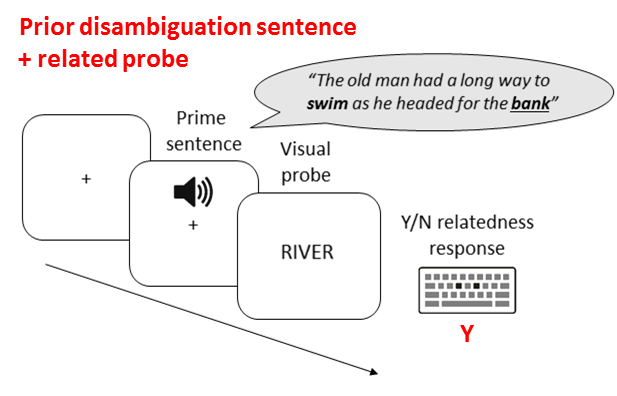

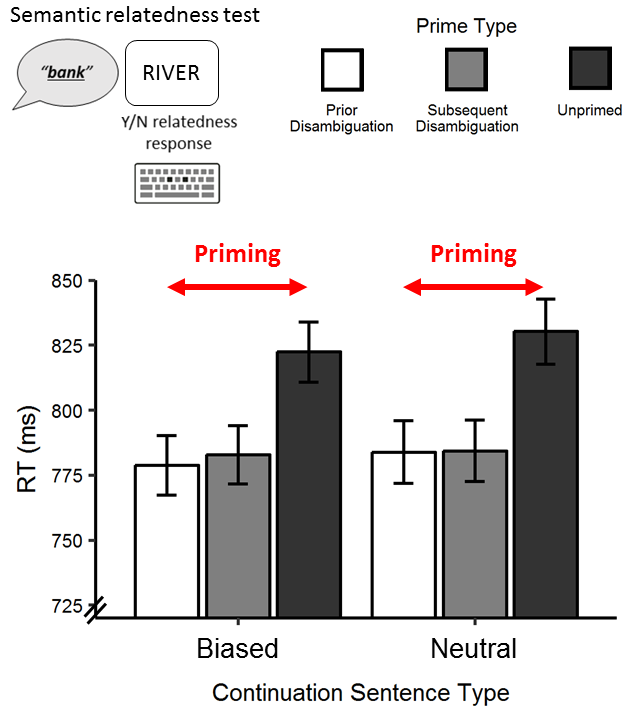

In 2 expts, we presented prime sentences in a semantic relatedness task. A word appeared after the sentence, and ppts made a Y/N judgment about whether the sentence and word meanings were related. At first it was looking like more priming with prior disambiguation sentences.

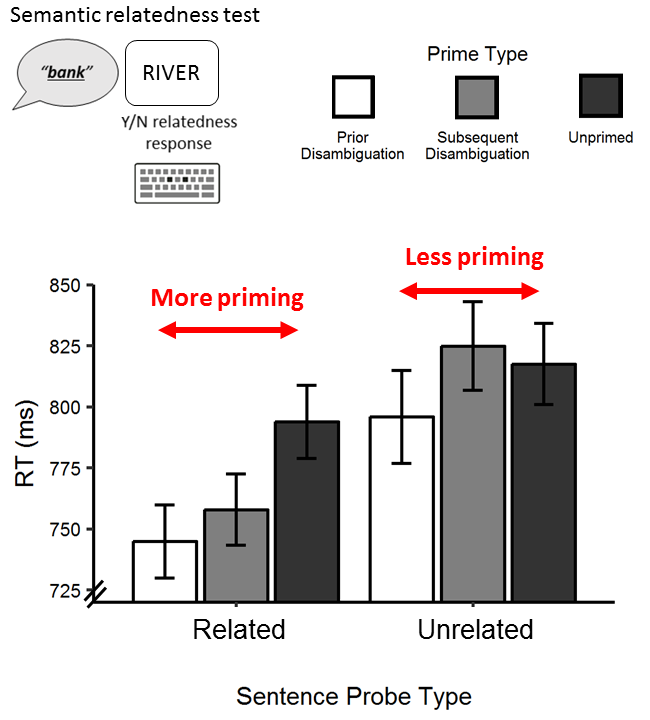

But then – and here’s the shock twist - we also saw more priming when the prime sentence was followed by a semantically-related probe word, compared to an unrelated probe word.

Huh? We didn’t expect probe relatedness to affect priming. Ok, 2 more hypotheses: 1. Related probes help people understand the sentences. 2. Unrelated probes interfere with sentence comprehension b/c participants can respond ‘No’ without (re)analysing the ambiguity.

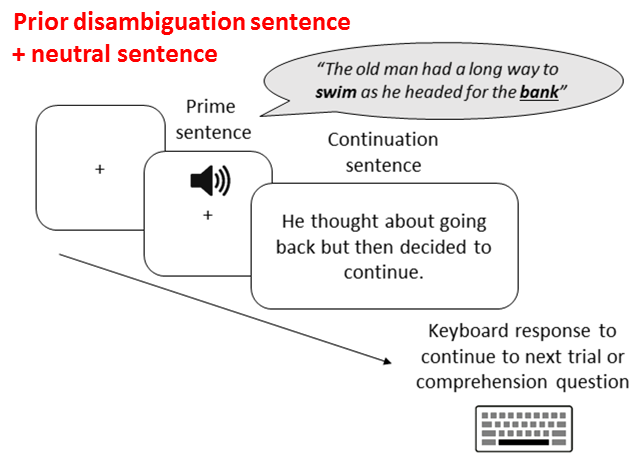

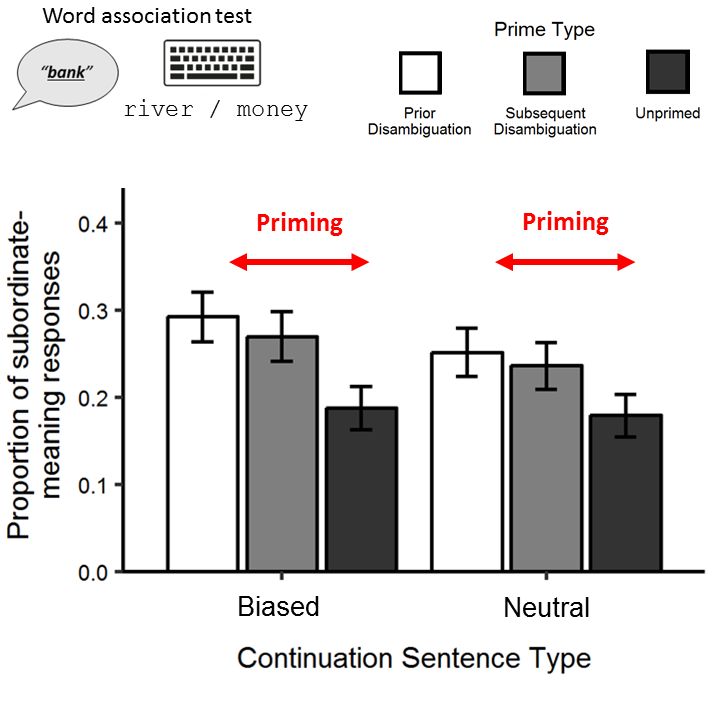

2 more expts! Prime sentence (“Sally worried that the BALL…”) then a 2nd sentence: biased to the correct meaning (“She had already bought a formal dress so…”) or neutral, (“She was the type of person who…”). We saw priming for ALL conditions, and no differences between them.

Summary: word-meaning priming can occur for both sentence types. BUT priming for harder-to-understand subsequent disambiguation sentences changes with task context: when participants can do the prime task without re-analysing the ambiguity, we don’t see significant priming.

This is consistent with the ‘good enough’ view of language processing: representations can remain as (im)precise as required to do the task. Lexical-semantic retuning seems to operate on the output of a good-enough interpretation.

What does it all mean for our research question? Well, it seems that that fine-tuning of word meanings is driven by listener’s *final* interpretation of an ambiguous word in a sentence, regardless of the path that they take to get there.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter