I.

You got the sense from spending any time around him that Pap knew some shit.

And I don’t mean dead languages or Auden’s poetry or a Wittgenstein aphorism, though he read often and he knew a thing or two about those too. But James Farrell knew some shit.

You got the sense from spending any time around him that Pap knew some shit.

And I don’t mean dead languages or Auden’s poetry or a Wittgenstein aphorism, though he read often and he knew a thing or two about those too. But James Farrell knew some shit.

It was the understated look of disappointment on his face when the soda hit his tongue. It was how he cocked his hat slightly to the left. It was how he discarded loser cards when he played a game of gin.

It was how he laughed so tight and so deep, and how he would stare—the only time he really ever looked at you—when he laughed, a stare of such intensity, like a tiger pacing its cage.

It was how he held his cigarette, those withered, nicotine-stained fingers of his left hand lifting the Marlboro and then drawing a long, luxurious pull and then he would rest it and stare down at his right.

He didn’t drink anymore, Pap, but he smoked like a chimney. It was his shock of red hair, still thick and full after all these years.

My mother laughed, at the end of it all, that the booze destroyed so many things, but it never took his hair.

My mother laughed, at the end of it all, that the booze destroyed so many things, but it never took his hair.

Pap, he knew some things you might not want to know, or that you might try to forget if you did. Pap knew how not to die, but I suspect Pap knew how not to die in ways that would make many people not want to live.

Pap knew how to give unearned violence too. Pap knew how to drink an entire bottle of vodka in under five minutes. He knew how to live on the streets of Chicago and not freeze to death in an alley there.

Pap knew how to abandon his wife and six children for long stretches of time, because he couldn’t face what he knew and, equally, because he couldn’t face what he didn’t know.

What he didn’t know. James Farrell knew so many things you’ll never know, that you wouldn’t want to know, but *what he didn’t know*—it was everything.

II.

It is 1918 and a boy’s mother dies. She’s dying with thousands of others, lying in a ward a few miles from her tenement apartment on Chicago’s south side.

Our boy’s father does not stay with his children, though he cannot be with his wife, quarantined as she is.

It is 1918 and a boy’s mother dies. She’s dying with thousands of others, lying in a ward a few miles from her tenement apartment on Chicago’s south side.

Our boy’s father does not stay with his children, though he cannot be with his wife, quarantined as she is.

His oldest daughter married well and stayed in Cork. The oldest child living with him in Chicago, a boy, but not *our* boy, is not yet thirteen, too young still to look after his five siblings.

He asks the woman across the hall to keep an eye on the youngest two and our boy’s father leaves the apartment, perhaps to weep in the privacy of the street, perhaps to drink until he is numb, or perhaps to claim and bury his wife’s body.

What happens next is odd even by the standards of a strange and ill time. The woman across the hall takes the two youngest children—our boy and his younger brother—to the train station.

There she boards a train to Milwaukee with her common-law husband. Our boy’s father will never see any of them again. He dies a few years later: suicide by bottle, they say.

III.

Pap was a prolific storyteller. If I have painted him as a forbidding character it is only half the story.

He was a curmudgeon and a crab, to be sure. He was a man who had lived a hard life, but he could also charm you, or anyone, particularly small children.

Pap was a prolific storyteller. If I have painted him as a forbidding character it is only half the story.

He was a curmudgeon and a crab, to be sure. He was a man who had lived a hard life, but he could also charm you, or anyone, particularly small children.

And he knew some fine stories, stories that could make a small child roll on the floor with laughter, sides splitting, the silliness of it all. Pap also wrote poetry and short stories, but he never published them. He locked away his words in notebooks.

Pap talked openly of his silly, impossible dream of being a police officer, a dream that came not, I think, from an overcompensating desire for power or from stale machismo.

It came from an attachment to an image: a large police officer picks up a small boy, hugs him close to his shoulder, his big hand cups the back of the boy’s head.

Pap was also prone to puns, sly witticisms, delightfully nonsensical malapropisms and neologisms, and even droll, well-placed asides. He was irreverent and wicked, and disliked authority instinctively, his obsession with the police notwithstanding.

My mother recounted the day he took her on a trip to downtown Fort Wayne. It ended with her waiting outside of a bar well after dark, but sometime midday—perhaps two whiskeys before four—they’d run into an evangelist on a corner.

“Do you believe Jesus Christ is your lord and savior? Are you a Christian, sir?”

Pap winked at my mother and then, with his distinctive grin, stare, and laugh, he barked back at the street preacher, “Why, no, sir, I’m a devout, lifelong heathen!”

Pap winked at my mother and then, with his distinctive grin, stare, and laugh, he barked back at the street preacher, “Why, no, sir, I’m a devout, lifelong heathen!”

IV.

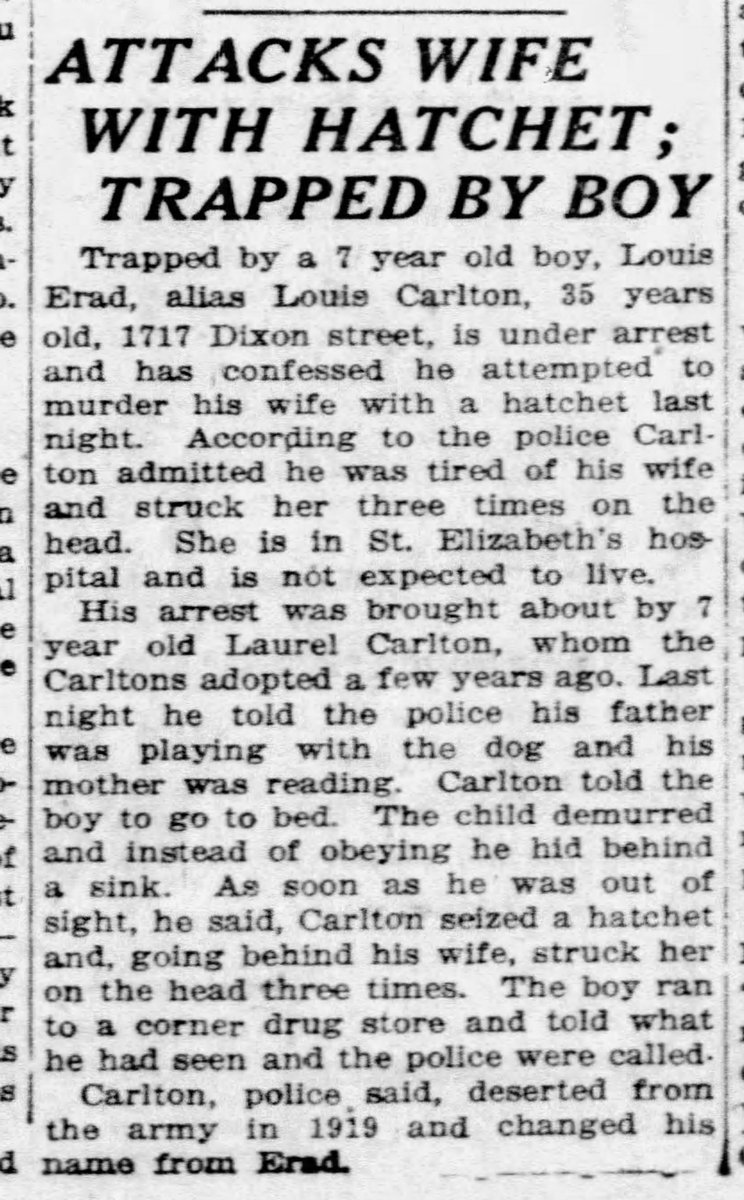

The newspapers tell it this way: Laurel Erard hid under the sink. At this time, sinks had curtains rather than cabinetry beneath, and Laurel was a small boy.

The newspapers tell it this way: Laurel Erard hid under the sink. At this time, sinks had curtains rather than cabinetry beneath, and Laurel was a small boy.

It seems implausible that Louis Erard would not have seen Laurel, even concealed behind this curtain, but Louis was drunk and angry and he never gave much thought to Laurel in any case, except for beatings when he was bored and drunk.

Laurel watched from behind this curtain as Louis sank his hatchet into the face of Jessie LeFleur, his common-law wife, three times. When Louis stumbled out of that apartment on the south side of Chicago in December of 1923, Laurel wasted no time.

Laurel ran. And he ran until he found a police officer and he dragged the police officer back to the apartment. And maybe the police officer picked him up then, cradled him to his shoulder, and cupped the back of Laurel’s head with his hand.

V.

James Farrell died in a VA hospital in Fort Wayne, Indiana on a Friday night in the autumn of 1996. The news came during my high school football game. My coach pulled me aside after the game and delivered the news with the absurd directive not to cry.

James Farrell died in a VA hospital in Fort Wayne, Indiana on a Friday night in the autumn of 1996. The news came during my high school football game. My coach pulled me aside after the game and delivered the news with the absurd directive not to cry.

Did I cry? Pap had lingered near death for so long. He had only outlived Ma’am by a few weeks and the whole family had spent most of the month in mourning. We were all cried out.

But I think I made myself cry anyway, if only because I thought—or intuitively knew—that it completed the circuit of my coach’s absurd directive and somehow made the directive less absurd.

My coach was not a bad man, or even a stupid man. Far from it, he was a kind man who, facing a bad situation, said something stupid. In spite of the stupidity, crying became the polite thing to do if only to justify, like a call and response, my coach’s words.

And so, to justify a manhood entirely alien to Pap and myself both, I wept for my grandfather, there, in my pads, helmet hanging at my side, already anticipating the slow, grey drive to Fort Wayne for Pap’s funeral.

VI.

Pap once shared what he said was his single fondest childhood memory. At the time, his father and mother and he were living in a cabin, probably some place in the Dakotas, making money running whiskey down from Canada.

Pap once shared what he said was his single fondest childhood memory. At the time, his father and mother and he were living in a cabin, probably some place in the Dakotas, making money running whiskey down from Canada.

Pap, though still a small boy, had many chores. One was to draw water from a stream and bring it up to the cabin.

On one such occasion, Pap was confronted by an irate rattlesnake in the middle of the path.

On one such occasion, Pap was confronted by an irate rattlesnake in the middle of the path.

VII.

I had my first taste of whiskey at Pap’s wake: we sipped the family poison. I don’t think I’ve seen my mother drink whiskey before or since, but she drank it then, propelled, I think, by the need, at last, for a symmetry.

I had my first taste of whiskey at Pap’s wake: we sipped the family poison. I don’t think I’ve seen my mother drink whiskey before or since, but she drank it then, propelled, I think, by the need, at last, for a symmetry.

IIX.

Pap said he froze when he saw the rattlesnake. The way he told it, Pap thought he was a goner and began preparing to meet his maker, as best as a six-year-old can make such preparations.

Pap said he froze when he saw the rattlesnake. The way he told it, Pap thought he was a goner and began preparing to meet his maker, as best as a six-year-old can make such preparations.

Before the snake could strike, or perhaps just as it began to strike, the edge of a hatchet, tossed from over Pap’s shoulder, caught the snake and separated its head from its body.

Pap’s father didn’t say much but he retrieved his hatchet and sent Pap on his way. Pap recalled that his father kept that hatchet with him at all times, flipping it as a nervous tick.

Pap said he took the body of that snake and when he got to the stream he swung it over his head in a circle with all his strength.

And he swung the snake’s body around and around for ages—a timeless whirling there in that sunny stream—a freedom surging through his body, until, exhausted, he hurled it with a splash far into the cold waters.

Pap was ecstatic, or he remembered that he was ecstatic. And perhaps he misremembered or willed himself to believe what was not true at the time. But I choose to believe that, there in the open of the stream, he was ecstatic.

IX.

There were problems with the bills from Pap’s care and death. It had come at the VA. But we couldn’t establish Pap’s identity to the VA’s satisfaction, the same problem that made it impossible for Pap to get a Social Security Card when he was alive.

There were problems with the bills from Pap’s care and death. It had come at the VA. But we couldn’t establish Pap’s identity to the VA’s satisfaction, the same problem that made it impossible for Pap to get a Social Security Card when he was alive.

The root of the problem: No one—not Pap, not Ma’am, not any of their six children, not any of his brothers and sisters—no one had ever located a birth certificate or a record of birth for James Farrell.

As far as the written word was concerned, James Farrell had only begun to exist sometime in December of 1923. My mother is a miracle when it comes to fighting—and beating—bureaucracies, and somehow she bested the VA, evidence of identity or not.

But the issue was not merely one of tidy record keeping.

My mother tells me that sometimes when Pap was deep in his cups—when he was in a melancholy drunk rather than a violent one—Pap would mutter a refrain or mantra.

“I don’t know my own name.”

My mother tells me that sometimes when Pap was deep in his cups—when he was in a melancholy drunk rather than a violent one—Pap would mutter a refrain or mantra.

“I don’t know my own name.”

Had James Farrell forgotten his own name?

You’d be surprised by the things you can never learn to forget.

You’d be surprised by the things you can never learn to forget.

IX.

It made for sensational press. Louis Erard was apprehended. His common-law wife clung to life in a hospital. Even if his son, Laurel, had not saved his mother, his quick thinking brought her justice, and that was something.

It made for sensational press. Louis Erard was apprehended. His common-law wife clung to life in a hospital. Even if his son, Laurel, had not saved his mother, his quick thinking brought her justice, and that was something.

And what a strange and wonderful boy he was, the newspapers said. He was quiet and unfailingly polite. And despite the squalor and moral turpitude of his family, he could read.

The newspapers said that Laurel had taught himself to read from his mother’s bible. It was the only way he could entertain himself when his parents, living as they had out in the Dakotas, had locked him in a cabin and headed to town to drink and dance.

They had only recently arrived in Chicago, the newspapers said, moving into the apartment with the sink with the curtain behind which Laurel hid as his father in his drunken rage took the hatchet to his mother.

Louis Erard was a known quantity to the police. He had deserted from the Army and run off with a rich man’s wife from Kalamazoo, a rich man named LeFleur. He had gone by many names to evade the police. His most common alias was Louis Carlton.

X.

I never met any of pap’s brothers or sisters. It seems that many were bitterly estranged from Pap. I do not know that he ever met his sister Mary, who lived in Ireland.

I never met any of pap’s brothers or sisters. It seems that many were bitterly estranged from Pap. I do not know that he ever met his sister Mary, who lived in Ireland.

Mary denied Pap was even her brother, that he was any kind of Farrell at all. John and Emmett may have felt similarly, though they did not deny the blood relation explicitly.

Joseph, Pap’s sole younger brother, did not, of course, even consider himself a Farrell, having been raised by a middle-class family in Milwaukee with the name Krause. Pap was close only with the two siblings he had lived with in the orphanage in Skokie: Danny and Maggie.

Danny was a bad influence on Pap. It’s hard to know for certain, but my aunts and uncles seem to suggest that Danny had a way of sending Pap on spiraling benders.

He’d drop in on the family every few years and he’d invite Pap to go and “reminisce” for a night. Depending on how much money the two had on them, Pap might not resurface for days or weeks. Once he was gone for longer.

It had also been that way in their youth. Pap arrived at the orphanage and been reunited with Danny and Maggie in early 1924. But it was Danny who had convinced Pap to run away from the orphanage in Skokie in the spring of 1930.

The two boys schemed to ride the rails out to Utah and find their older brother John, who wrote to Maggie occasionally about his family and homestead. And they hoboed out to Utah and found John.

John’s wife was not pleased to meet them, nor to add two more mouths to the family. She had sent them packing not long after their arrival. They hoboed their way back to Chicago, arriving on the rails in the dead of winter 1930, without penny, home, or friend.

XI.

For all his polite demeanor and gentle erudition, there was something obviously off about Laurel. He was a pale, freckled boy, with a full shock of bright red hair.

For all his polite demeanor and gentle erudition, there was something obviously off about Laurel. He was a pale, freckled boy, with a full shock of bright red hair.

Louis Erard, however, was a towering, swarthy man. Jessi too had long dark hair. When pressed, though she was barely able to maintain consciousness, at first she claimed they had adopted Laurel. But then Jessi had let the full story spill.

They had stolen Laurel, and his brother too, some years earlier from a man here in Chicago. She could not recall the man’s name, only that he was a neighbor, that his wife had died in the influenza epidemic, and that they had taken the boys in the confusion of her death.

She had wanted a child, she said, though she had convinced Louis they would be able to sell both of the boys in Milwaukee. Later, she would not part with the older of the stolen boys, would not let Louis take him, though Louis took his younger brother.

They had raised the boy, our boy, Laurel, as their own son, living in cabins and wagons in remote country quarters. Louis ran booze, leaving Jessi and Laurel for months on end.

The newspapers spilled buckets of ink. A woman came forward. She claimed to know Laurel’s true identity. She said she had known Laurel’s real father and mother, had watched his true father weep when he learned that his two youngest sons had been stolen.

She had watched as Laurel’s true father drink himself to death to drown the grief.

The boy’s true name, she said, was not Laurel at all. He was the lost son of the now-deceased John Farrell. His real name was James Farrell.

The boy’s true name, she said, was not Laurel at all. He was the lost son of the now-deceased John Farrell. His real name was James Farrell.

XII.

You can imagine that Pap and Danny’s situation in that cold winter was dire. But Danny had a scheme. Danny told Pap that he’d heard of a theater. It was a theater where men who liked boys went.

You can imagine that Pap and Danny’s situation in that cold winter was dire. But Danny had a scheme. Danny told Pap that he’d heard of a theater. It was a theater where men who liked boys went.

And the two of them – Pap and Danny – would head to that theater. Pap would linger until he was approached by a man who sought his company. He would lure the man to an alley where Danny was waiting and they would knock the man out cold and steal his wallet.

XIIV.

Little Jimmy Farrell the newspapers dubbed the pale and polite boy. He became something of cause célèbre in the Chicago press. A policeman, a man named Sullivan, would look after him until suitable arrangements could be made for his permanent care.

Little Jimmy Farrell the newspapers dubbed the pale and polite boy. He became something of cause célèbre in the Chicago press. A policeman, a man named Sullivan, would look after him until suitable arrangements could be made for his permanent care.

Sullivan, they said, welcomed Jimmy into his home and treated him like a son. Jimmy, they reported, had fast made an innocent crush on Sullivan’s only daughter, the aptly named Sunshine.

Pap told a different story. Pap said that Sullivan told him he would be his father and that Sunshine would be his sister. And Pap was overflowing with joy at this turn of events.

He had, after all, never liked his cruel parents – though, in spite of their cruelty, he missed them terribly – and they weren’t his parents at all, but his kidnappers, a thing that made little sense to him, but that circumstances demanded he accept.

Sullivan enrolled him at a diocesan school. On the first day, a nun had handed Pap a tablet of paper and a pencil, which, to Pap, were unimaginable luxuries. Then the nun sat him at a desk.

Pap said he found it hard to concentrate on much beside the pencil and paper. To own them, he said, outstripped his wildest fantasies. He sat in the classroom in a dazed bliss, clutching the pencil and tablet, as the other children filed out for recess.

Upon their return, the other children in Pap’s class discovered their own pencils and tablets had vanished from their desks. The nuns located the items in Pap’s satchel. Pap ran then, out of the school, into the street, and finally to a nearby park.

He said, so many years later, that he had not known why he took the other tablets and pencils. He had no plan to use them or sell them. But they had seemed like such unimaginable treasures, that he had grasped as many as he could.

It was after dark when Sullivan found him in the park, cold, terrified, and weeping in a thicket of bushes. Pap never said, and I can only speculate, that Sullivan picked up Pap, held him tight to his shoulder, and cupped the back of Pap’s head with his hand.

I am sorry for what happens next, because it seems, even for a story of such cruelty, to be too much, too cruel. But it is how the story goes.

Sullivan took Pap, placed him in the back of his car, and after a drive, deposited him at an orphanage in Skokie. Sullivan never spoke a word on the drive or when he left him, and Pap never saw Sullivan or Sunshine again.

XIV.

A man approached Pap outside the theater in that frigid Chicago winter.

“Is the boy waiting in that alley with you?” the man asked.

Pap panicked and nodded yes.

A man approached Pap outside the theater in that frigid Chicago winter.

“Is the boy waiting in that alley with you?” the man asked.

Pap panicked and nodded yes.

“I know what you’re up to, and you’re bound to get yourself killed.”

Pap stood captivated and terrified. The man told Pap to fetch Danny from the alley, and Frank – the man’s name was Frank, you see – bought them to dinner at a nearby diner.

Pap stood captivated and terrified. The man told Pap to fetch Danny from the alley, and Frank – the man’s name was Frank, you see – bought them to dinner at a nearby diner.

Midway through the meal, Danny pulled Pap aside. Frank, he said, was a solid fellow, and Pap should stick with him. Moments later, Danny ran out on them, leaving Pap with Frank.

Pap lived with Frank for six years. Pap moved out only after he met, courted, and married my grandmother, Ma’am, sometime around 1937.

XV.

Some of this you’ll have to take on Pap’s not entirely reliable word. But I saw, as a child, crumbling newspaper articles, and, as an adult, I looked those articles up. The stories are there if you trust the Chicago press circa 1923 any more than you trust Pap.

Some of this you’ll have to take on Pap’s not entirely reliable word. But I saw, as a child, crumbling newspaper articles, and, as an adult, I looked those articles up. The stories are there if you trust the Chicago press circa 1923 any more than you trust Pap.

But what a strange little conspiracy that would be: the same bizarre story, across these several newspapers, each with photographs taken from different angles by different photographers of the same boy at roughly the very same moment.

I wonder if all these angles might have reversed the apocryphal myth of primitives terrified that the camera would steal their souls: so many cameras, crossing the same space, summoning from the void a boy, or the story of a boy.

What haunted my grandfather more than all the pain was the possibility that what little past those crumbling papers gave him, those too might be a lie. This is perhaps what he meant when he said he did not know his own name.

When the hatchet cleaved his world it orphaned him, not to his family, which was hardly a family at all, but to a past, any past. All pasts were lost in that moment, irreparably lost for all time to float down a stream like the body of a headless snake.

Fin.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter