I did a talk in the excellent @MarkusEconomist Academy series yesterday on “Do Debt and Deficits Matter Anymore.” You can watch the video, see the slides, or read this longish thread for a summary.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwZnLVoiHi0&feature=youtu.be">https://www.youtube.com/watch... https://www.dropbox.com/s/lb2btgbadotwxcf/20201119%20Princeton%20Debt.pdf?dl=0">https://www.dropbox.com/s/lb2btgb... https://www.youtube.com/watch...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwZnLVoiHi0&feature=youtu.be">https://www.youtube.com/watch... https://www.dropbox.com/s/lb2btgbadotwxcf/20201119%20Princeton%20Debt.pdf?dl=0">https://www.dropbox.com/s/lb2btgb... https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Short version my points:

1. Don’t worry re debt in current emergency. But do ask whether scarce resources meet a cost-benefit test.

2. Best metric is real net interest/GDP, look ahead ~one decade

3. Target 1% of GDP in real net interest/GDP, which is 150-200% of GDP in debt

1. Don’t worry re debt in current emergency. But do ask whether scarce resources meet a cost-benefit test.

2. Best metric is real net interest/GDP, look ahead ~one decade

3. Target 1% of GDP in real net interest/GDP, which is 150-200% of GDP in debt

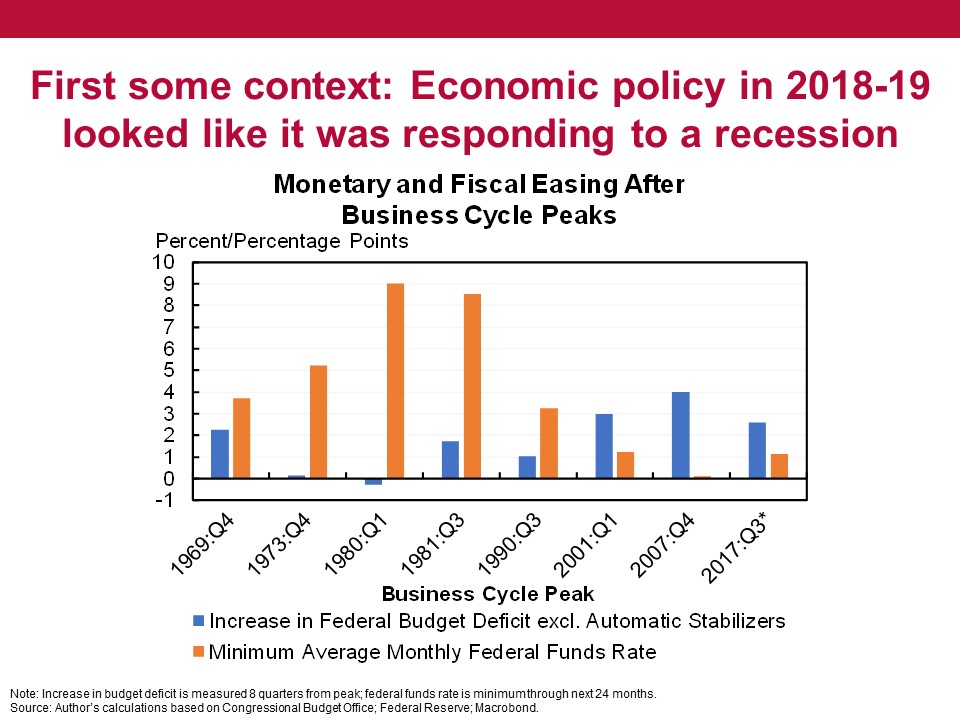

Before getting to my points some context. Macro policy in 2018-19 was extraordinary, more like the response to a moderate to severe recession. That this was needed to generate reasonable growth is due to long-term decline in interest rates.

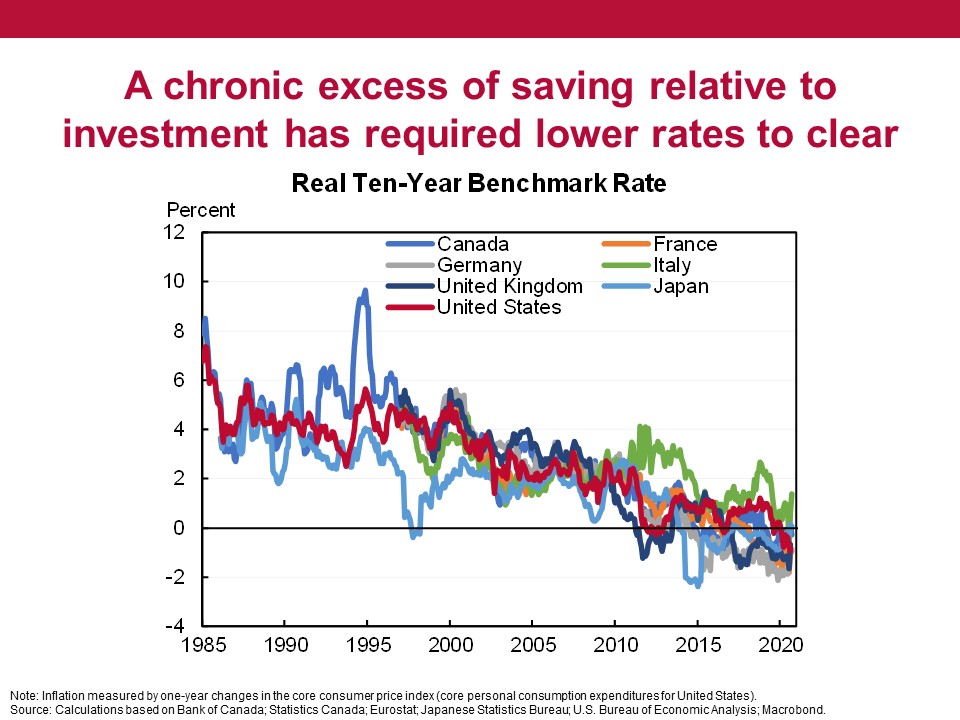

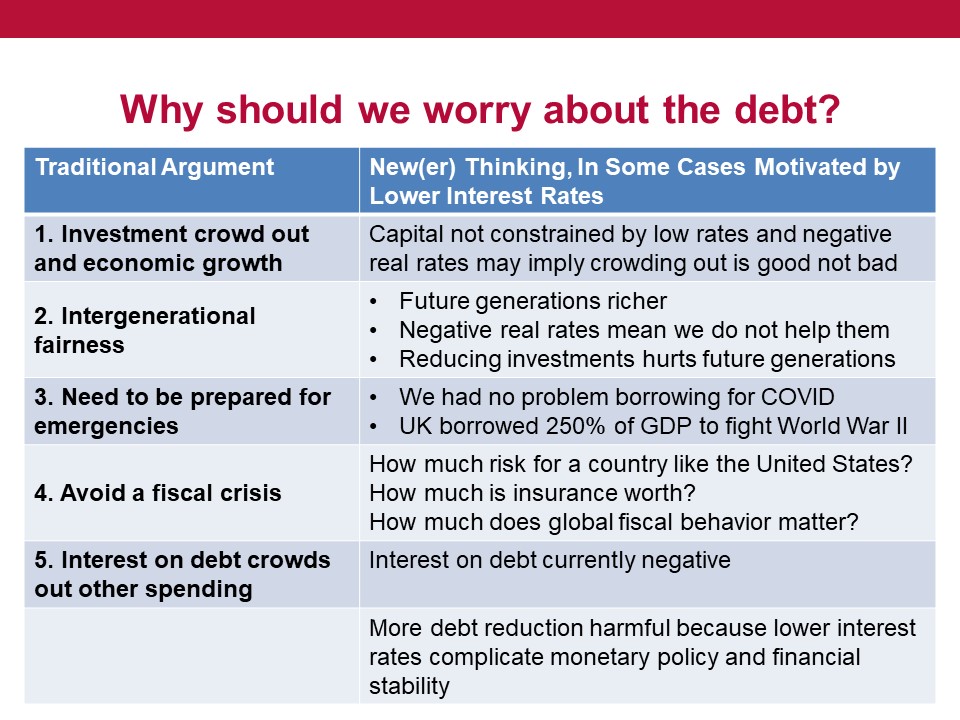

Long-term decline in rates should change how we think about fiscal issues. Many of the traditional arguments for debt concern are less operative now (& may not have been operative before). If worried about low rates causing financial instability that is an argument for more debt.

We don’t need to worry about debt in the immediate response. This doesn’t mean do anything, it means figure out top-down the right macro size or do a bottom-up calculation of cost-benefit for the allocation of scarce resources.

There is broad agreement among economists and policymakers that *now* is not the time to worry about debt. There is less agreement about *when*, if ever, to worry. Fair to say many economists getting less worried but still no agreement.

MMT and extreme fiscal hawks provide two views. One de facto says never worry and the other says always worry (I say de facto because MMT constantly offers various exceptions but then downplays them in policy advice). These are like stopped clocks, right twice a day.

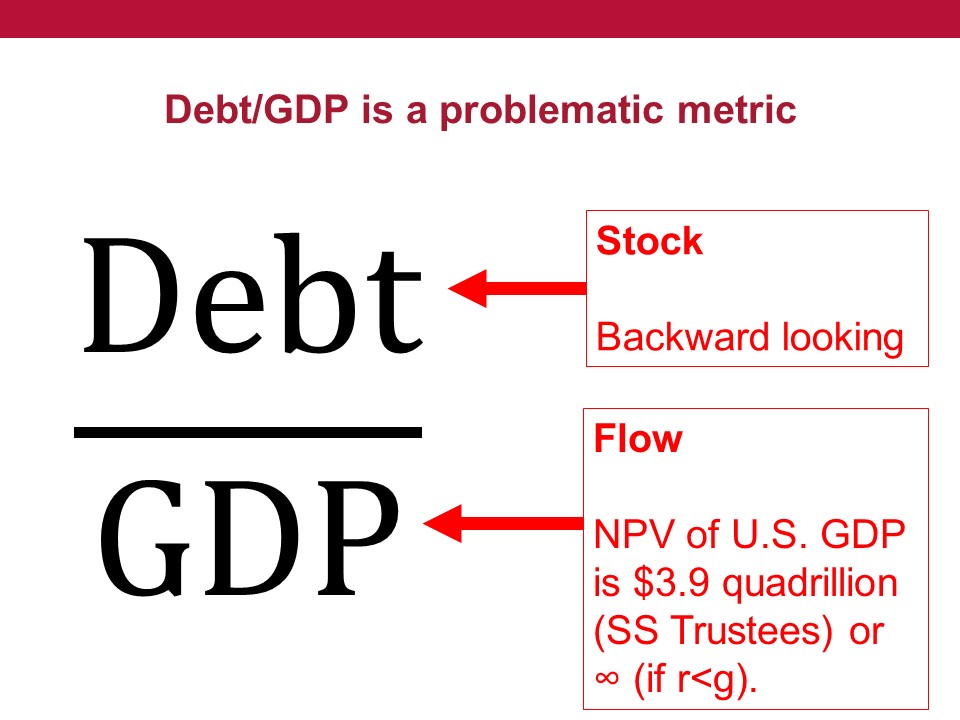

We all are very used to looking at debt/GDP as a fiscal metric, I’ve looked at it myself and shown it thousands of times. But that doesn’t make it right, and it suffers from several severe defects that make it misleading as a primary guide to fiscal space and the fiscal situation

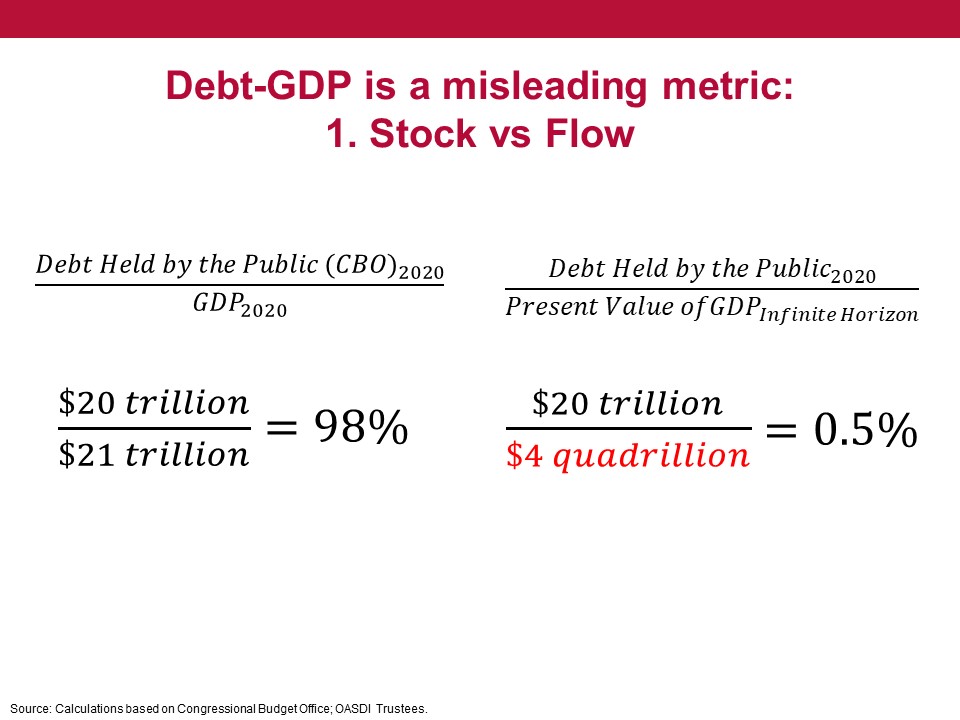

Issue 1: Debt is a stock (a total you have at one time) and GDP is a flow (the total over a period of time). Better to compare stocks to stocks (or flows to flows). Not hard to pay off $20T of debt when US GDP totals about $4 quadrillion going forward.

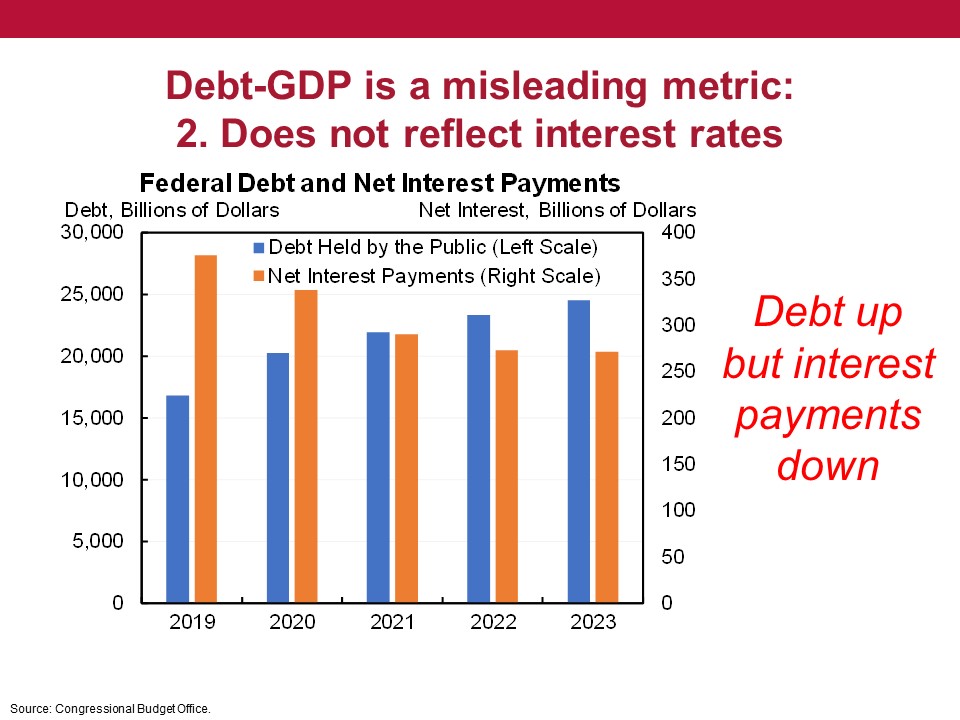

Issue 2: Interest rates have fallen. As a result, while the debt is rising over the next several years interest payments on the debt are actually falling (in nominal dollars).

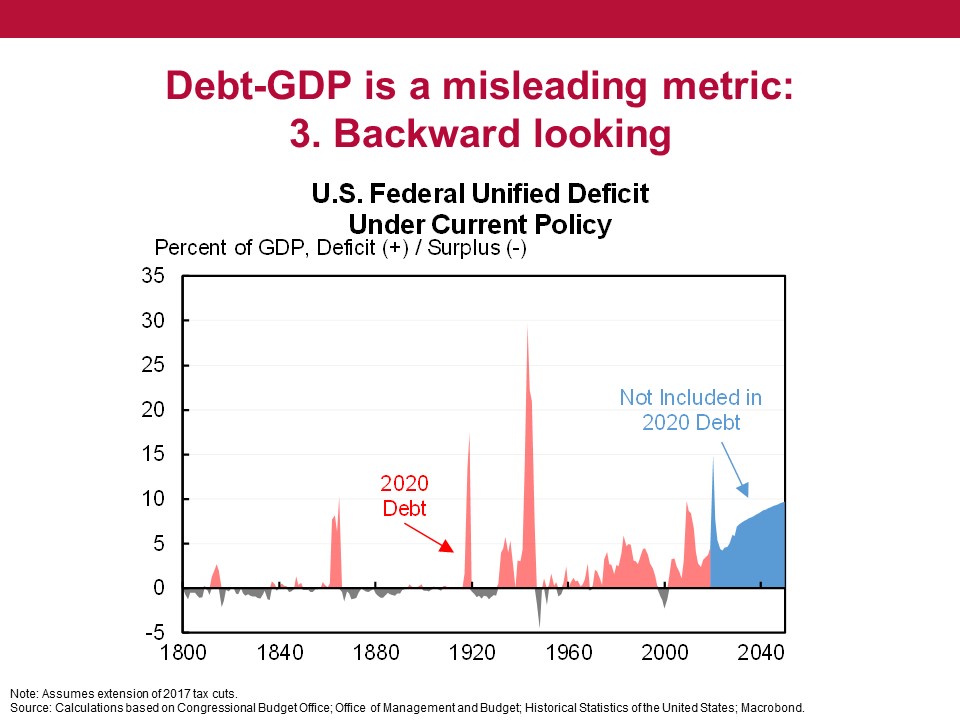

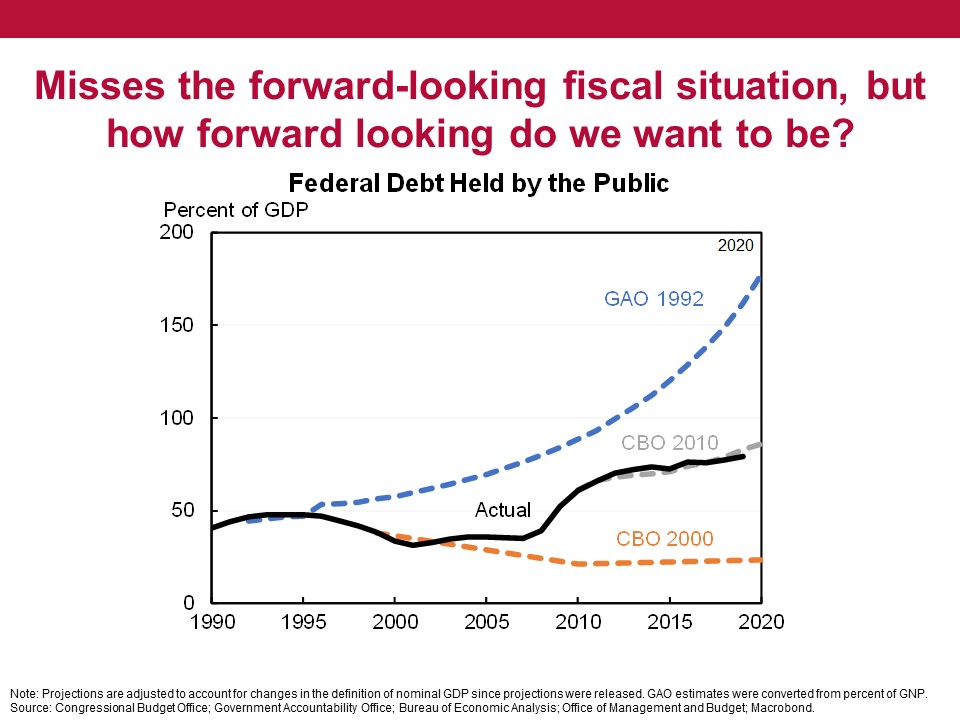

Issue 3: Debt is backward looking, it is the total cumulative deficits from 1789 to the present (give or take). Doesn’t reflect what is happening in the future.

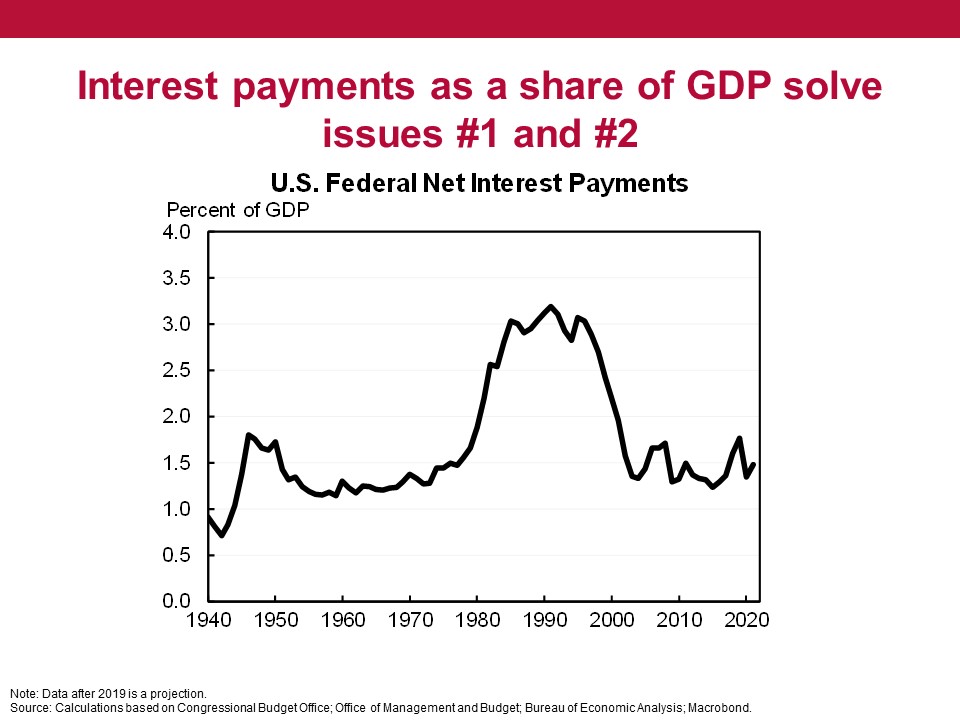

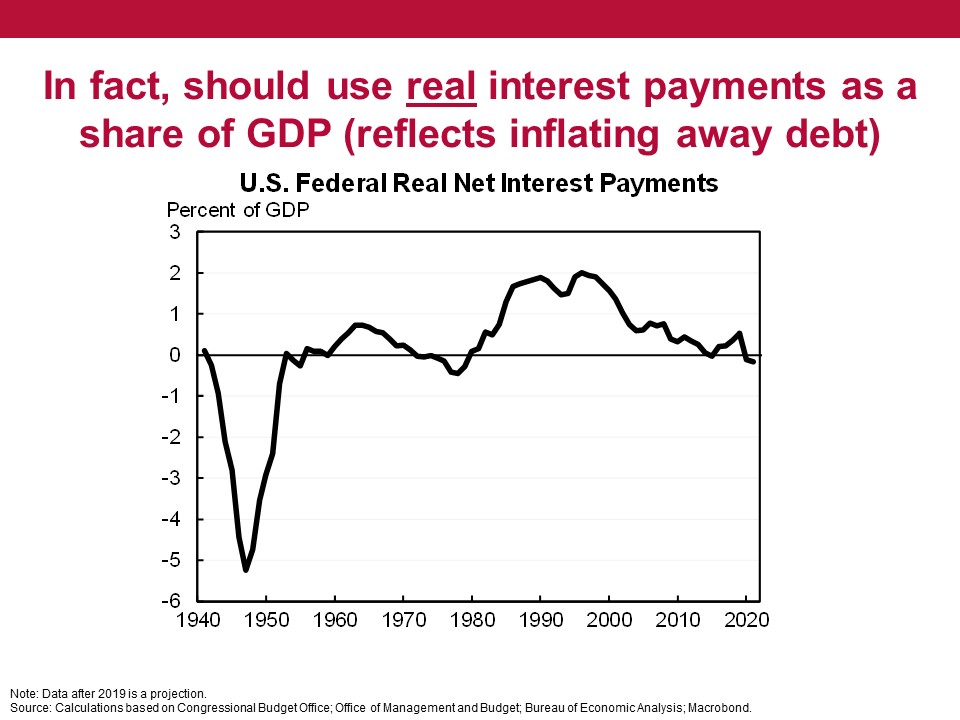

Issues #1 and #2 can be solved by shifting to focus on interest/GDP as a metric. This shows debt currently very manageable. In fact, a better metric is real interest/GDP which subtracts the portion of the debt that is inflated away. Even more affordable.

Issue #3 says be forward looking. One way to do that is the fiscal gap. But an issue is that forecasts of the future are very uncertain. 30 years ago we thought debt/GDP would be nearly 200% in 2020. Better not to make large policy changes today based on a very uncertain future.

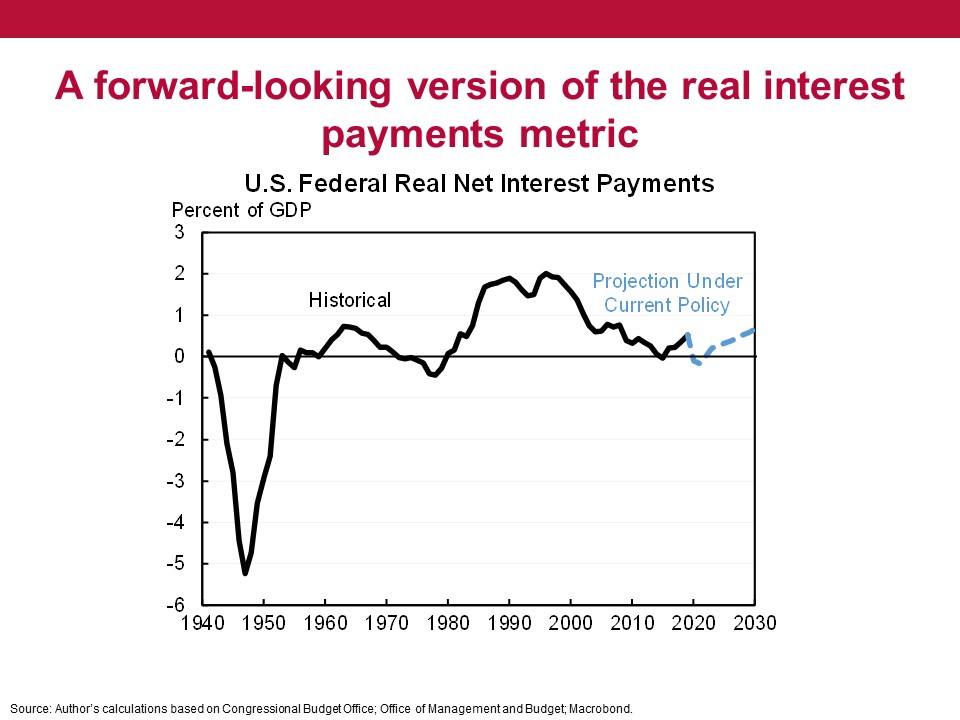

My own preference is to look at real net interest/GDP but project forward something like 10 years. This is a bit arbitrary but a way of saying emphasize what we have a tiny bit more clarity about and disregard what we have much less clarity about.

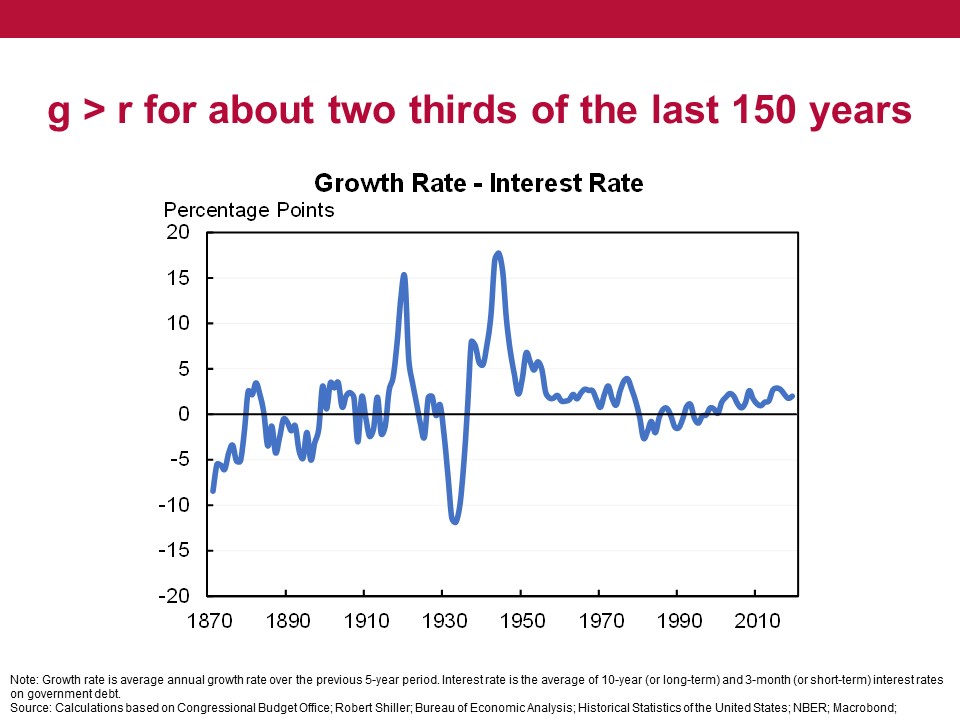

Finally, should we have a fiscal target and if so, what should it be? For this we need a view on g - r. About two thirds of the last 150 years it has been positive, meaning you can run a primary deficit (deficit excluding interest) and still have stable debt.

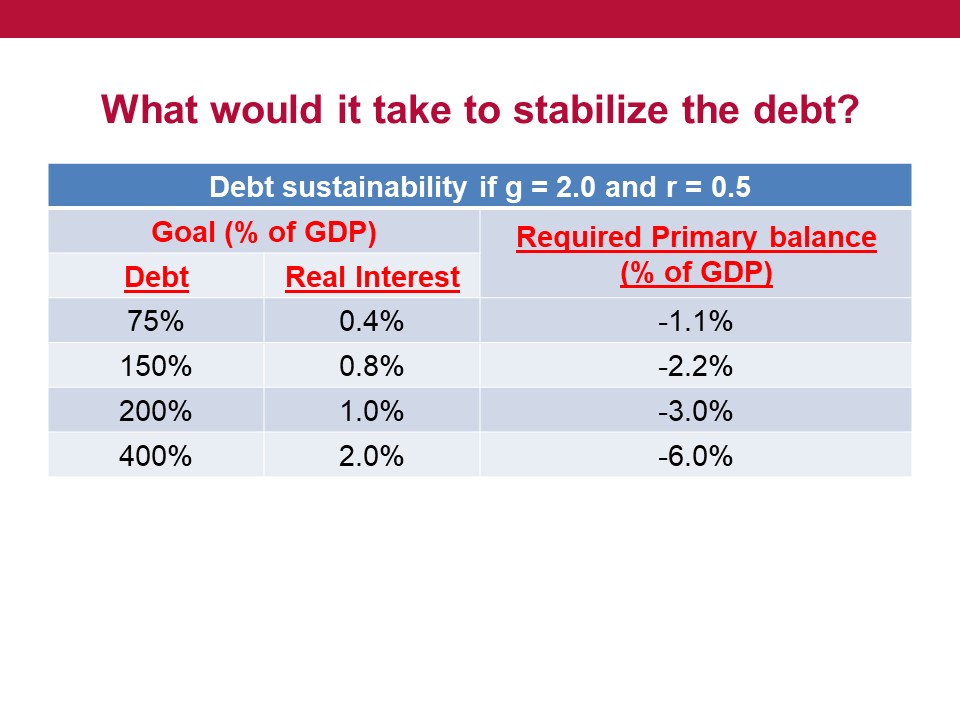

But g > r does not give unlimited license, still a specific primary deficit compatible with a specific debt goal. This gives a range of them and also shows the associated net interest assuming g - r = 1.5, about what CBO expects for 2030.

Translating this into specific policy we need to have some combination of: optimal, understandable and achievable.

Some policies do well on some dimensions but badly on others (e.g., balanced budget is understandable but bad policy and not achievable).

Some policies do well on some dimensions but badly on others (e.g., balanced budget is understandable but bad policy and not achievable).

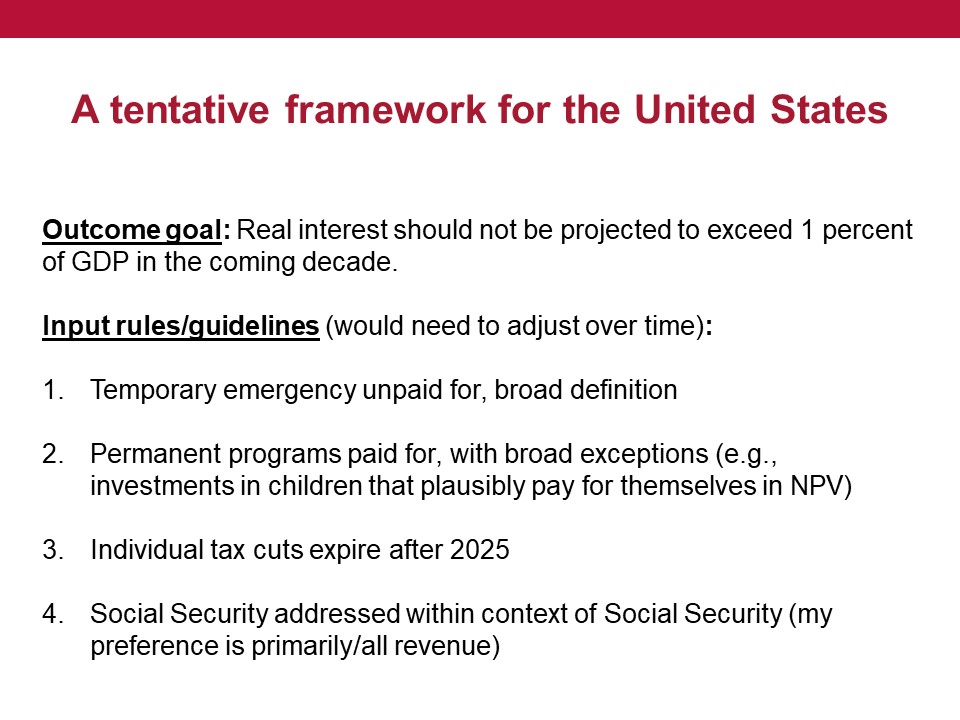

Tentative proposal is goal of real net interest 1% percent of GDP. Based on current projections could:

1. Emergency spending unpaid for, broad defn

2. Permanent spending paid for, with broad exceptions

3. Tax cuts expire in 2025

4. Reform Social Security (ideally w/ revenues)

1. Emergency spending unpaid for, broad defn

2. Permanent spending paid for, with broad exceptions

3. Tax cuts expire in 2025

4. Reform Social Security (ideally w/ revenues)

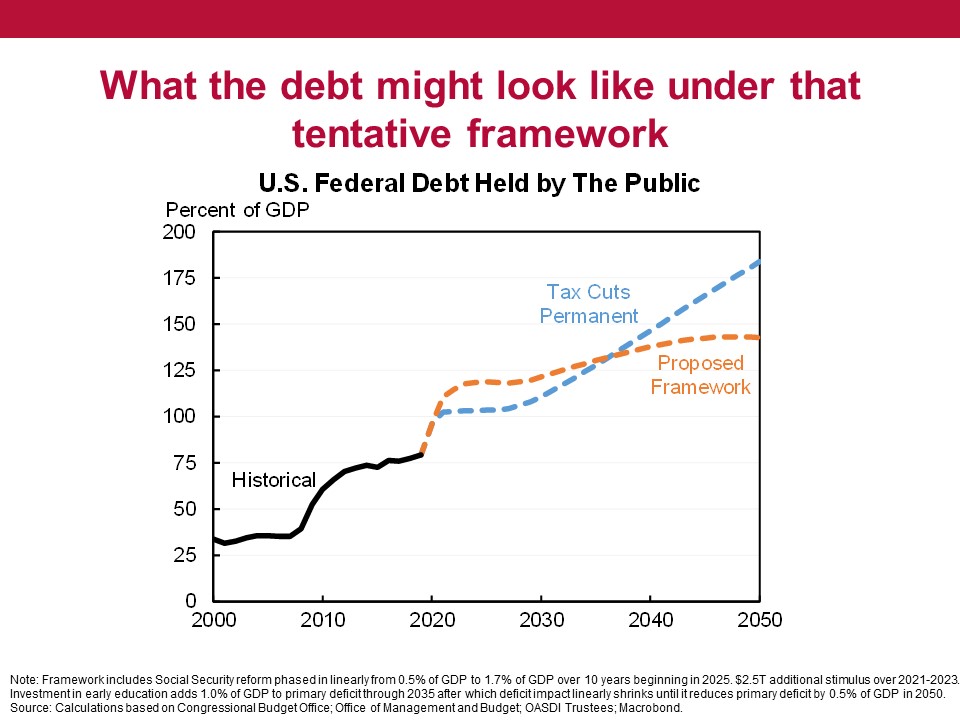

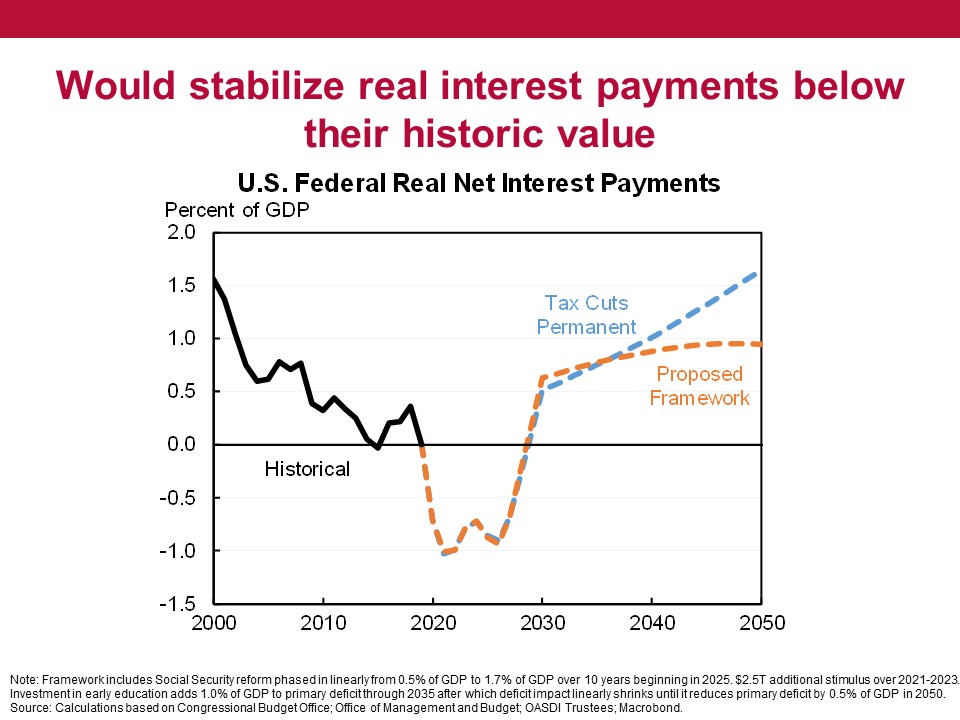

To give a sense of what this would mean, higher debt than the current baseline through about 2035 but then leveling off around 150% of GDP. Real net interest stabilizing around 1% of GDP. But, again, would mostly focus on the next decade, forecasts have massive errors after that.

Thanks for putting up with this long thread, maybe it would have been even shorter to watch the talk itself. You can do so here. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SwZnLVoiHi0&feature=youtu.be">https://www.youtube.com/watch... https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter