From 1996,

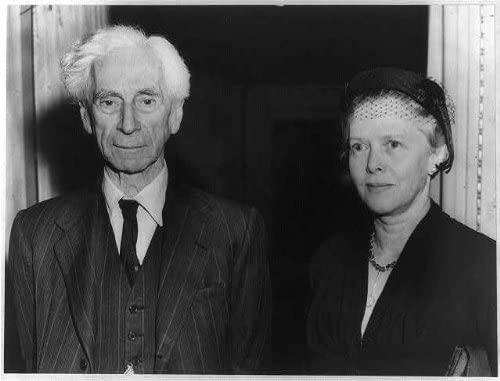

Bertrand Russell& #39;s vast contribution to Western thinking was largely a consequence of his personal loneliness and misanthropy, argues Ray Monk https://www.independent.co.uk/news/principles-of-passion-and-hatred-1303845.html">https://www.independent.co.uk/news/prin...

Bertrand Russell& #39;s vast contribution to Western thinking was largely a consequence of his personal loneliness and misanthropy, argues Ray Monk https://www.independent.co.uk/news/principles-of-passion-and-hatred-1303845.html">https://www.independent.co.uk/news/prin...

Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) led and inspired several waves of popular protest, ranging from the movement against conscription in the First World War to the campaigns against the nuclear deterrent in the 1950s and against the Vietnam War in the 1960s.

Wherever he lived, a bust of Voltaire stood on his mantelpiece.

In 1958, he published (in French) an article called & #39;Voltaire& #39;s Influence On Me& #39; that emphasized the connections.

In 1958, he published (in French) an article called & #39;Voltaire& #39;s Influence On Me& #39; that emphasized the connections.

Russell wanted to be Voltaire, but actually felt himself to be more like a character from a Dostoevsky novel.

He wanted to be ruled by cold reason precisely because he felt himself to be driven by deep, irrational fears and impulses.

He wanted to be ruled by cold reason precisely because he felt himself to be driven by deep, irrational fears and impulses.

Russell had an extraordinary and disturbing ability to hide even his strongest feelings from those around him.

When he was irritated, he could appear charming.

When he was passionately aroused, he could appear coldly indifferent.

When he was irritated, he could appear charming.

When he was passionately aroused, he could appear coldly indifferent.

It was a trait that had been built up from long years of isolation as a child, when, as he said later, "the most important hours of my day were those that I spent alone in the garden, and the most vivid part of my existence was solitary".

He was brought up by his grandmother, Countess Russell, the widow of the great Victorian Prime Minister, Lord John Russell, his mother having died when he was two, his father when he was three and his grandfather when he was six.

Lady Russell was pious and sentimental, and Russell quickly learnt to conceal from her those thoughts and feelings of which she might disapprove, which included almost all the thoughts and feelings most dear to him.

Denied the opportunity to express himself orally, Russell took to writing everything down.

An enormous amount of his writing is concerned with himself, revealing the feelings he kept hidden and trying to make sense of the conflicts that characterized his intellectual life.

An enormous amount of his writing is concerned with himself, revealing the feelings he kept hidden and trying to make sense of the conflicts that characterized his intellectual life.

"Most of the people jarred me, misanthropy and misogyny settled on me like a cloud. At night, I didn& #39;t kiss Alys often enough, and she began to cry when I put out the light, but I did nothing to comfort her."

For much of his life Russell felt, as he often put it, like a ghost, a quasi-substantial being, unable to make real contact with the flesh-and-blood creatures around him.

The intense passion that Russell kept locked up was, he often thought, akin to madness and frequently, when emotionally aroused, he thought himself on the brink of insanity.

His Uncle Willy had gone insane and, after murdering a complete stranger, had spent the rest of his life hidden away in an asylum.

Russell did not know this until he was 21, and ever afterwards his very deepest fear was of reliving his uncle& #39;s fate.

Russell did not know this until he was 21, and ever afterwards his very deepest fear was of reliving his uncle& #39;s fate.

"Russell& #39;s relations with men, while never sexual, were also often stormy and frequently unsuccessful.

Monk& #39;s account of his disastrous friendship with D. H. Lawrence is searing to read." https://www.nytimes.com/1996/12/06/books/more-adept-with-concepts-than-people.html">https://www.nytimes.com/1996/12/0...

Monk& #39;s account of his disastrous friendship with D. H. Lawrence is searing to read." https://www.nytimes.com/1996/12/06/books/more-adept-with-concepts-than-people.html">https://www.nytimes.com/1996/12/0...

According to Monk, it was Russell& #39;s failure as a parent that produced in his son and grandchildren the schizophrenia that destroyed their lives.

This "was the final visitation of the ghosts that haunted Russell throughout his life."

This "was the final visitation of the ghosts that haunted Russell throughout his life."

Of his four wives, only the last, Edith Finch, made Russell happy.

His passion for the wife of Alfred North Whitehead, Russell& #39;s collaborator in the three-volume Principia Mathematica, ended his friendship with Whitehead.

His passion for the wife of Alfred North Whitehead, Russell& #39;s collaborator in the three-volume Principia Mathematica, ended his friendship with Whitehead.

Russell, in fact, seems to have had a thing about married women.

He had affairs with the balmy wife of poet T.S. Eliot and with the immensely tall, intelligent and mysteriously attractive Ottoline Morrell, wife of Philip Morrell, a member of Parliament.

He had affairs with the balmy wife of poet T.S. Eliot and with the immensely tall, intelligent and mysteriously attractive Ottoline Morrell, wife of Philip Morrell, a member of Parliament.

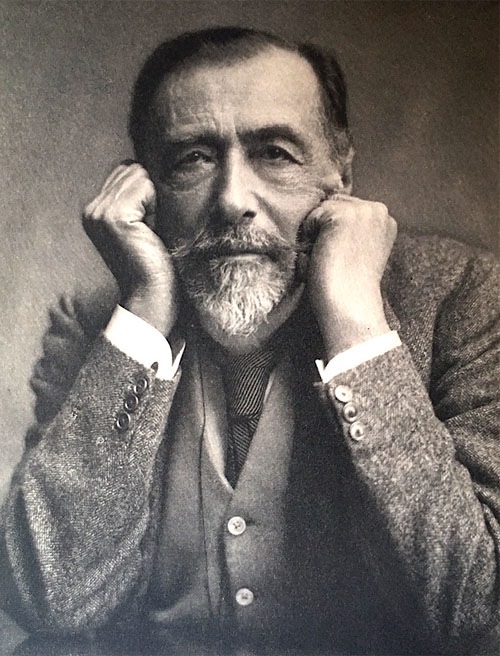

Russell& #39;s deepest and most enduring attachment, however, seems to have been with novelist Joseph Conrad (1857 –1924) .

Of his first meeting with the writer, Russell wrote: "I plucked up courage to tell him... It was impossible to say how much I loved him."

Of his first meeting with the writer, Russell wrote: "I plucked up courage to tell him... It was impossible to say how much I loved him."

Conrad and Russell met only a few times. Their surviving letters are mainly thank-you notes for books.

Yet Russell named his sons after Conrad: John Conrad Russell and Conrad Russell; the latter eluded the curse of madness and became a distinguished historian.

Yet Russell named his sons after Conrad: John Conrad Russell and Conrad Russell; the latter eluded the curse of madness and became a distinguished historian.

What attracted Russell to Conrad was not the man himself but his books.

Of these, Heart of Darkness and Amy Foster, "might be regarded as dramatizations of Russell& #39;s deepest fears and anxieties, of his terror of madness and of his acute sense of isolation."

Of these, Heart of Darkness and Amy Foster, "might be regarded as dramatizations of Russell& #39;s deepest fears and anxieties, of his terror of madness and of his acute sense of isolation."

In Russell& #39;s autobiography, he calls civilized life "a dangerous walk on a thin crust of barely cooled lava which at any moment might break and let the unwary sink into fiery depths."

Russell was in effect two persons: on the one hand the philosopher, and on the other a writer of "second-rate journalism," hastily written articles with such come-hither titles as "How to Be Free and Happy," "Is Modern Marriage a Failure?" and "Why I Am Not a Christian."

It was, however, a work that Monk might consign to the rubbish heap that led to a Nobel Prize for Russell: The History of Western Philosophy, an international best seller.

Because Nobel Prizes aren& #39;t awarded for mathematics or philosophy, Russell& #39;s prize was for literature.

Because Nobel Prizes aren& #39;t awarded for mathematics or philosophy, Russell& #39;s prize was for literature.

In his old age, when Russell long since had wearied of philosophy, he came under the spell of an enigmatic and, to some, malign figure, Ralph Schoenman, an American who wrote statements and articles that appeared under Russell& #39;s name.

His father’s family, who traced their lineage back to the time of the Norman Conquest, had a proud history of fighting for their beliefs; Russell was brought up to believe that opposition is a healthy and necessary political activity.

There is a severe deficit of literature describing Russell’s third marriage to the young Patricia Spence, who was 22 to Russell’s 64 years when they tied the knot in 1936.

Their bond spanned 13 years, ending cacophonously in 1949. The subsequent rift foiled Russell’s relationship with Conrad, who did not again see his father until the winter of 1968, a meeting which, for both of them, caused a permanent breach with Patricia.

World War I radicalized Russell. Soon, his anti-war protests first cost him his teaching position at Trinity College in 1916 and later landed him in jail for six months.

His thoughts, consistently complex, often lost their nuance when regurgitated by mass media, and soon he’d been accused of wholeheartedly siding with Lenin’s version of communism over the West’s “muscular capitalism.”

From the moment he started living in China in 1920, he was relieved to find a far saner civilization than the Western model he’d grown accustomed to: “The Chinese are gentle, urbane, seeking only justice and freedom,” Russell once wrote.

However, as he too would later wonder about Japan, Russell was concerned about China becoming too Westernized, thus polluting a society that has worked and progressed for centuries without the infringement of Western force.

Russell took with him his mistress Dora Black. The Chinese reacted in an embarassed though proper manner.

Russell reacted with ironic amusement; shortly after their arrival he wrote to Trinity College to resign his position as Lecturer on the grounds that he was ‘living in sin.’

Russell reacted with ironic amusement; shortly after their arrival he wrote to Trinity College to resign his position as Lecturer on the grounds that he was ‘living in sin.’

This contrasted sharply with the outraged attitude of the British Foreign Office, which even considered having Russell evicted from China because Russell "would certainly prove subversive and dangerous to British interests at a Chinese educational institution."

While the Chinese would have no part of any British scheme to get Russell out of China, the Foreign Office did manage, shortly after his arrival, to get him on a list of murderers, spies and other disreputable characters listed under “Suspected Persons”.

The Russian Revolution inspired the Chinese revolutionary movement in other ways largely because of the apparent good will toward China, including its stated willingness to return the Chinese Eastern Railroad, renunciation of the Czarist unequal treaties, and other generous acts.

Russell said, "I went to Russia a Communist, but contact with those who have no doubts has intensified a thousandfold my own doubts, not as to Communism itself, but as to the wisdom of holding a creed so firmly that for its sake men are willing to inflict widespread misery."

Russell attributed the despotism of Bolshevism to Russian character traits rather than to communist principles, implying that Bolshevism& #39;s ruthless and despotic qualities need not be part of communism in other countries.

Wang Jingwei is another example of the fluidity of politics: a man who moved from being a primary spokesman for nationalist revolution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to an interest in Marxism–Leninism in the 1920s, and then moved into the KMT.

In certain circles in China, ‘state socialism’ was already a popular idea in the early 1900s.

Both Russell and these early advocates of state socialism in China seemed to derive their model from the movement toward state socialism as practised in Germany and Austria.

Both Russell and these early advocates of state socialism in China seemed to derive their model from the movement toward state socialism as practised in Germany and Austria.

Even Marx recognized that socialism, as a transitional stage between capitalism and communism, necessarily retained certain capitalist characteristics.

Some Chinese socialists in the early 1920 presumed that an orderly progression through stages toward communism was required.

Some Chinese socialists in the early 1920 presumed that an orderly progression through stages toward communism was required.

Liang Qichao apparently held quite similar views.

He worried about the failure of nationalization unless there was a sufficient number of technicians, a public concern for the welfare of the state, and codification of laws and regulations.

He worried about the failure of nationalization unless there was a sufficient number of technicians, a public concern for the welfare of the state, and codification of laws and regulations.

Liang had argued that the priority for development of the Chinese economy would have to be to encourage capitalism.

Protecting the proletariat would be secondary.

Protecting the proletariat would be secondary.

In a private letter, Russell indicates a real fear of class war: "If the class war becomes world wide, the issue will be neither the establishment of communism nor the re-establishment of capitalism, but the ruin of industry/education, and the downfall of our whole civilization."

Arguably, Russell also developed a consequentialist attitude towards pacifism itself. He grew more and more wary of peace for peace’s sake, although he unabashedly clamored for peace negotiations.

The Problem of China might imply an anti-Chinese tone. Far from it. Instead Russell predicts China’s resurgence and looks at the strengths of its civilization.

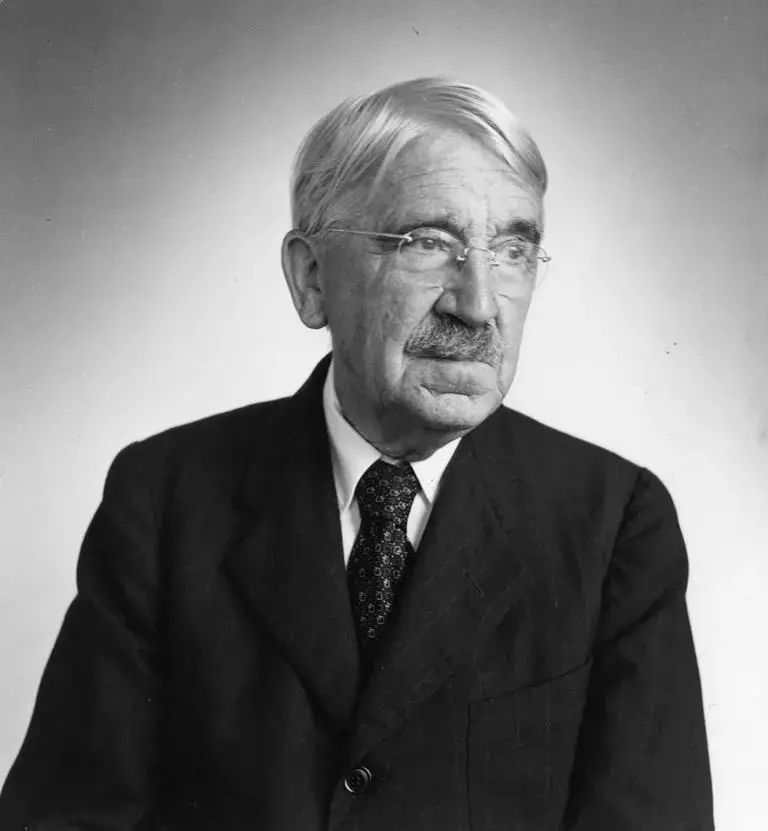

John Dewey and Bertrand Russell visited China at around the same time in 1920. Both profoundly influenced China during the great transition period of this country.

Most of Russell’s work was meant for Western readers, not Chinese ones.

Scholars have also often treated Russell as an independent thinker and analyze his views of China in isolation.

Scholars have also often treated Russell as an independent thinker and analyze his views of China in isolation.

Although Russell reproduced intellectual condescension and cultural essentialism like other Orientalists, he was decidedly anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist, which separates him from them.

Russell first, if not foremost, needed a salary, a job, and material for saleable journalism.

His former lovers, in addition, expected “riveting travelogue writing”.

Liang Qichao’s invitation offered all of the above.

His former lovers, in addition, expected “riveting travelogue writing”.

Liang Qichao’s invitation offered all of the above.

The historical moment that he stumbled into, however, was anything but typical.

In 1911, the Qing dynasty had collapsed. Eight years later, in 1919, Chinese politicians and intellectuals were still struggling to determine how to move forward.

In 1911, the Qing dynasty had collapsed. Eight years later, in 1919, Chinese politicians and intellectuals were still struggling to determine how to move forward.

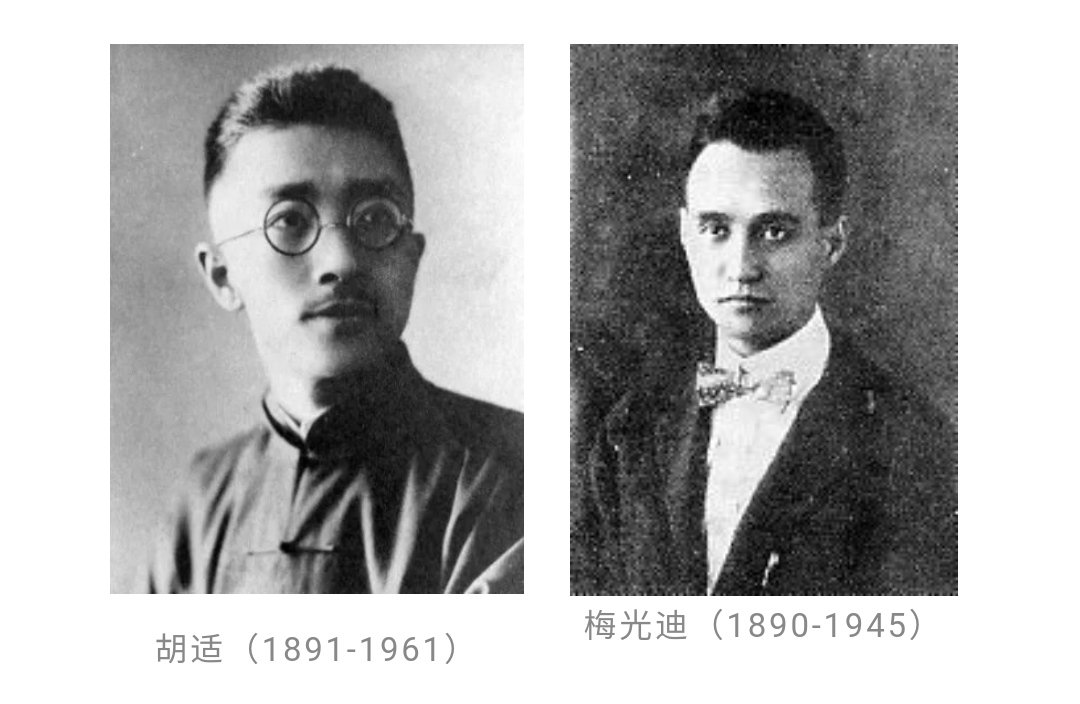

Hu Shih, a New Culture Movement leader and one of China’s premier public intellectuals, wrote an article titled “Intellectual China in 1919” that captures the moment.

New periodicals, he wrote, argued for modernization, scientific inquiry, and skepticism.

New periodicals, he wrote, argued for modernization, scientific inquiry, and skepticism.

Hu and his contemporaries confronted difficult questions, so they were eager to hear Western advice.

Since Russell was perceived as one the world’s premier social philosophers, expectations were particularly high for his visit.

Since Russell was perceived as one the world’s premier social philosophers, expectations were particularly high for his visit.

Upon arrival, Russell’s plans collapsed: he could not simply give the Chinese a few technical lectures.

He was surprised to find that his hosts wanted his advice on social issues, not technical philosophy.

He was surprised to find that his hosts wanted his advice on social issues, not technical philosophy.

This required him, as he described it, to go around “pretending to be a Sage” because “they [the Chinese] seem to think I must know by inspiration what they need.”

Although Russell made general claims, he did acknowledge his ignorance to his Chinese audience.

Russell began many lectures and articles with some recognition that he was not an expert and so his claims were only tentative.

Russell began many lectures and articles with some recognition that he was not an expert and so his claims were only tentative.

At least some of his audience members admired his reasonableness, and he was explicitly remembered as having never given “advice to the Chinese as to their immediate political difficulties”.

In 1920, Russell lectured to the Jiangsu Educational Society on “The Uses of Education”. He later published what seems to be the same lecture as a general article on education.

Even Russell’s recommendations on Chinese education were new versions of his pre-existing beliefs.

Even Russell’s recommendations on Chinese education were new versions of his pre-existing beliefs.

Russell’s views, sometimes inconsistent with his private opinions, gained geopolitical significance when he discussed Chinese politics and industrialization.

These two fields lie at the intersection of academic study, general concern, and the assertion of power.

These two fields lie at the intersection of academic study, general concern, and the assertion of power.

Russell, although he advised China to follow the Western path of industrialization, did advocate for domestic development and international socialism in place of development by Western powers.

Russell’s writing here implies a paradoxical power relationship in which China needed to develop to avoid Western domination, but could only do so through accepting Western methods and help.

Chinese politicians and intellectuals lent Russell their ears, but many ultimately disagreed with him.

These disagreements, though, were largely based on whether Russell agreed with their prior beliefs.

These disagreements, though, were largely based on whether Russell agreed with their prior beliefs.

Lu Xun, in a 1925 essay, criticized Russell’s rosy picture of Chinese peasant contentment, claiming that this contentment is what made China weak and conquerable.

What distinguishes Russell is that he used China to launch a non-trivial critique of Western political and cultural values.

Although this fits into the mould of “seeking answers in the East”, Russell’s intellectual independence is again notable.

Although this fits into the mould of “seeking answers in the East”, Russell’s intellectual independence is again notable.

Quite unfortunately, the bulk of The Problem of China discusses geopolitics based on a static and monolithic image of Chinese culture.

Witnessing a China in turmoil — warlords, demonstrations, strikes, the ever-present imperialist threats — Russell was both sympathetic and empathetic.

His trip overlapped with Dewey’s extended lecture tour, and there were short visits by Albert Einstein, Tagore, and many more.

His trip overlapped with Dewey’s extended lecture tour, and there were short visits by Albert Einstein, Tagore, and many more.

Unlike his backers in “Young China,” he had a great fondness for many aspect of the traditional culture.

He regarded with great skepticism plans to build up modern industry without taking into account of how it would actually benefit workers and ordinary consumers.

He regarded with great skepticism plans to build up modern industry without taking into account of how it would actually benefit workers and ordinary consumers.

By the traditional civilization, Russell meant courtesy, harmony, understatement, tolerance, a certain unworldliness — features that Russell directly contrasted to the Western lust for domination and that have perhaps become Oreintalist tropes of a certain kind.

Russell had every reason to like China. He was lionized; he could use Chinese civilization to criticize the West; he liked Chinese reformers, whom he hoped would lead China in a direction ultimately different from the capitalist-industrial-imperialist civilization of the West.

As it happened, China’s full induction into the world economic system was to await the war with Japan (1937-45), the Communist Revolution (1949), and three decades of real but autarkic development under Maoism.

Russell argued that "democracy presupposes a population that can read and write and that has some degree of knowledge as to political affairs. These conditions cannot be satisfied until at least a generation after the establishment of a government devoted to the public welfare."

Before he and Dora knew they were to be parents, Russell suffered a near-death experience.

In March 1921, he contracted pneumonia after bathing in hot springs near Beijing and was close to death on several occasions during the weeks that followed.

In March 1921, he contracted pneumonia after bathing in hot springs near Beijing and was close to death on several occasions during the weeks that followed.

His life was saved by the great efforts of a young doctor at the German Hospital, Franz Esser, with Dora’s help and the administration of some Chinese medication.

Russell changed tack because his work in logic reached the end of the line and he had a greater contribution to make as a public intellectual.

History has vindicated him: much of his popular writing stands the test of time better than his academic work. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/philosophy/what-people-get-wrong-about-bertrand-russell-philosophy-logic">https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/philosoph...

History has vindicated him: much of his popular writing stands the test of time better than his academic work. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/philosophy/what-people-get-wrong-about-bertrand-russell-philosophy-logic">https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/philosoph...

We might think that Russell treated religious belief too literally and it’s better understood as a form of life than a set of proto-scientific doctrines.

But he was simply taking on the religion of his time, which was dominated by literal clerics not postmodern theologians.

But he was simply taking on the religion of his time, which was dominated by literal clerics not postmodern theologians.

Much of what he once controversially advocated is now common sense, such as the need for honest sex education and the idea that “It seems absurd to ask people to enter upon a relation intended to be lifelong, without any previous knowledge as to their sexual compatibility.”

When Russell died, many obituarists reached for his remark that “Three passions, simple but strong, have governed my life: the longing for love, the search for knowledge and unbearable pity for the suffering of mankind.”

The New York Times ruefully noted that his longing for love was only satisfied in his 80s with marriage to his 4th wife; that his pity for humankind remained unbearable; and that of his search for knowledge, he himself had said “a little of this, but not much, I have achieved.”

John and Alice Dewey’s visit to Japan in 1919 and their subsequent sojourn in China from 1919 to 1921 are well documented/celebrated.

Dewey’s “Social & Political Philosophy” lecture series consisted of 16 lectures that he delivered at Peking University. https://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/408 ">https://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/408...

Dewey’s “Social & Political Philosophy” lecture series consisted of 16 lectures that he delivered at Peking University. https://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/408 ">https://journals.openedition.org/ejpap/408...

The Dewey lectures as published in Chinese were a product of a three-party collaboration that was twice removed from the original version, that is, from Dewey’s own typed notes and his delivery of them, through Hu’s interpretation, and, finally, to the recorder’s transcript.

Hu Shih lamented in a diary entry in 1922 that he could not find appropriate words in Chinese to render such simple terms in English as “tone,” “rhythm,” and “form.”

He was keenly aware of the poverty of vernacular Chinese vocabulary and the looseness of its syntax.

He was keenly aware of the poverty of vernacular Chinese vocabulary and the looseness of its syntax.

As Hu put Dewey’s ideas in words and phrases in vernacular Chinese, he simplified, conflated, emended, rearranged, and even expunged Dewey’s text, along with not infrequent translation mistakes.

Hu was enamored with “men of high ideals.” For he believed that society, and China of his times in particular, depended on these “men of high ideals” to provide guidance to dismantle the anachronistic and defective institutions and customs.

That Hu would substitute “socialism” for “communism” had nothing to do with fear of censorship. China was then divided, with regional warlords vying for power among themselves. They were too weak and too preoccupied with other priorities to exercise thought control.

While Hu was averse to Communism throughout his life, for almost thirty years until the early 1940s, he believed that socialism represented the latest phase of the development of the democratic ideal.

It is not just that democracy was a rallying cry of the New Culture Movement, of which Hu was its foremost leader, he genuinely believed democracy embodied the highest value of modern Western civilization, as testified by his hyperbolic phrase of the “religion of Democracy”.

He had no problem following Dewey’s differentiation between the state and the government.

He also appreciated Dewey’s reminder that “the government is itself composed of human beings having their own private interests, their own love of power and gain”.

He also appreciated Dewey’s reminder that “the government is itself composed of human beings having their own private interests, their own love of power and gain”.

Yet, Hu had difficulty seeing the state as anything but an instrument invented for the benefit of society in general.

He cared not who invented “the judge, the king, the law, and the state.” Nor would he consider it important to ask whose interests these inventions served.

He cared not who invented “the judge, the king, the law, and the state.” Nor would he consider it important to ask whose interests these inventions served.

Hu’s belief in the state as an instrument that could be harnessed to serve the public interest regardless of the power relations in society was closely tied to his organicist view of society, the third of the preoccupations that underpin his appropriation of Dewey.

Hu believed that there exists in society inequalities in the distribution of wealth, power, and intelligence, to be sure. But what look like inequalities at the individual level are nothing but nature’s way of fitting individuals to tasks suitable for them.

In the Chinese tradition, the “public” and the “private” were two antithetical concepts, with the former connoting “openness” and “fairness” and the latter “concealment” and “unseemliness.”

Hu’s social organicism complemented well this traditional ideal of “sublimating the private into the public” (化私为公) in that it enabled him to envision a society in which all members would follow a natural division of labor without being riven by class or group interests.

Hu cherished his public image as a staunch champion for democracy. He talked about democracy often, but mostly in general terms, never in the sustained and systematic manner as Dewey did.

More important, no translators are neutral or transparent conduits that decode ideas from one language to another.

When that translator happened to be the most celebrated intellectual leader of modern China, he was poised to stamp his imprint unequivocally on the translation.

When that translator happened to be the most celebrated intellectual leader of modern China, he was poised to stamp his imprint unequivocally on the translation.

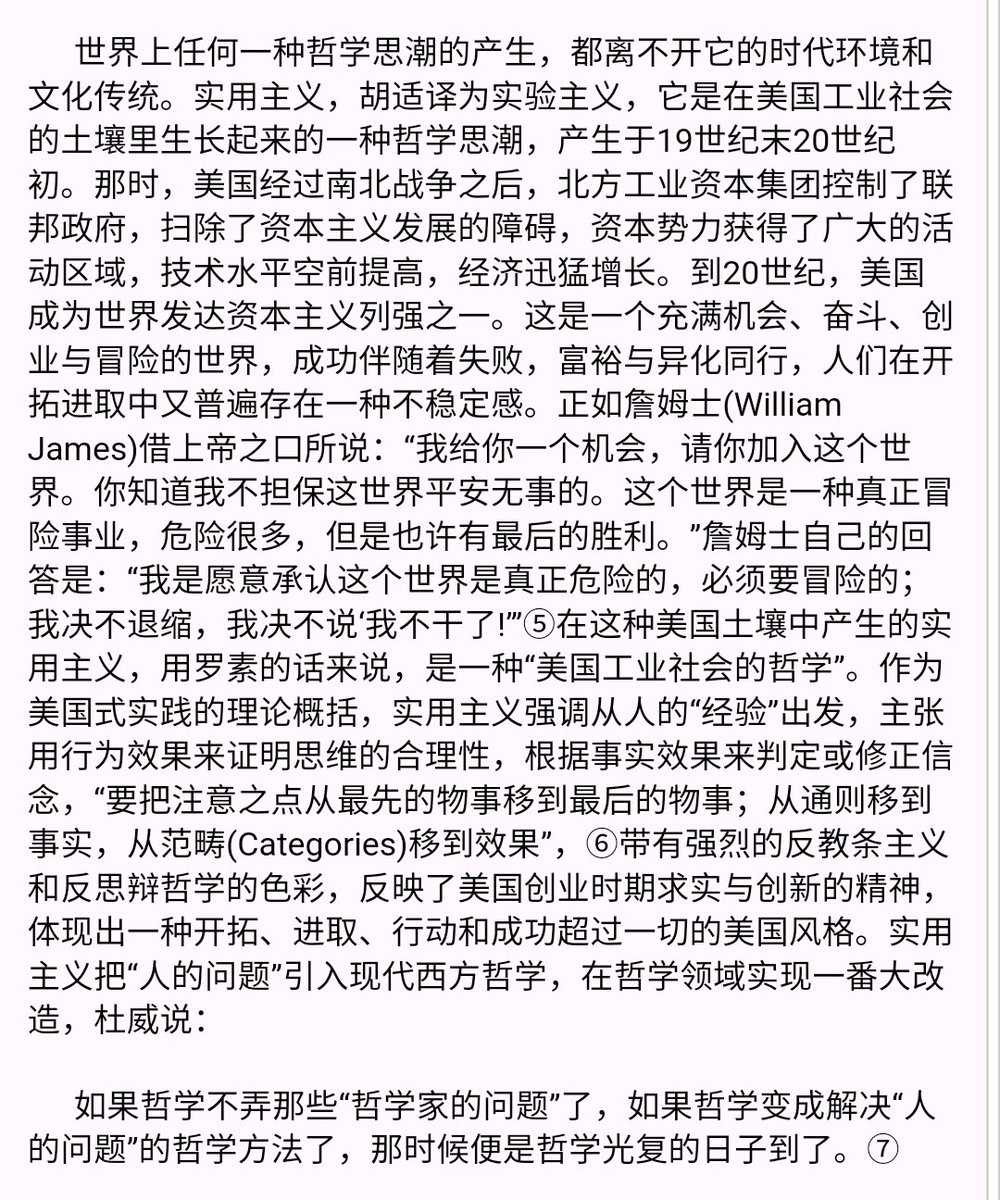

实用主义是在美国工业社会的土壤里生长起来的一种哲学思潮,产生于19世纪末20世纪初。当时,美国已经成为世界发达资本主义列强之一。作为美国式实践的理论概括,实用主义强调从人的“经验”出发,主张用行为效果来证明思维的合理性,带有强烈的反教条主义和反思辩哲学的色彩。

http://book.ifeng.com/special/wusiwenrenpu/list/200905/0501_6351_1135327.shtml">https://book.ifeng.com/special/w...

http://book.ifeng.com/special/wusiwenrenpu/list/200905/0501_6351_1135327.shtml">https://book.ifeng.com/special/w...

现代自由主义与经典自由主义的一个重大分歧在于是否承认个人利益与社会利益是天然和谐的。经典派认为只有去掉权威才有个人自由;现代派则认为为了社会自由也必须有社会约束,特别强调对某一个人的自由的约束是其他人自由的条件,同时允许并主张运用社会集体力量对经济等问题进行人为的调节和干预。

19 世纪美国思想界对英国情形所知最悉且追随亦紧。当社会主义在英国渐成显学时,其在美国的影响也日大。在进步主义初期的 1880 年代前后,社会主义在美国知识界非常风靡。只是因为种种社会历史和文化原因,当英国知识分子由自由主义迈向费边社会主义时,美国知识分子反从社会主义回归自由主义。

美国理想主义因与清教 (Puritanism) 的联系, 特别讲究理论框架和词句的紧密结构, 到 19、20世纪之交已成士人思想上的重负,很象中国理学在王阳明之前的状况, 这是实用主义得以成为显学的大背景。实用主义一旦进入社会政治领域, 所起的作用即是将理论研讨转向具体的问题。

余英时指出胡适在方法论的层次上把杜威的实验主义和中国考证学的传统汇合了起来, 是他的思想能够发生重大影响的主要原因之一。胡适在民国初年所写的那几篇论“问题与主义” 的文章堪称是他实验主义方法的典型表述。他借用了佛书上“ 论主” 这个词, 提出一切学说都是时代的产儿。

余英时在讨论美国的激进与保守时, 清楚地指出其间有一个大家接受的中心点,这是美国可以进行一点一滴的改革的根本基础。反观近代中国, 所缺的恰是这样一个大家接受的中心点;除了尊西趋新的大方向一致外, 各派各人对解决中国问题的方案是名符其实的五花八门,而且谁也说服不了谁。

贾祖麟 (J. B. Grieder) 注意到,温和的杜威到中国的胡适手里就变得激进了。他说, 杜威哲学的主要目的在于设法使失调的社会或文化重新获得和谐, 而胡适的态度则似乎与此相反。他在介绍杜威思想时转而强调“利用环境,征服他,约束他,支配他”。因此,他主张破坏旧传统,再造新文明。

胡适在 1930 年3 月与一位亲俄的法国人 Alfred Fabre-Luce 畅谈“ 几个钟头, 很相投”, 其主要内容即美国与苏俄的异同。Fabre-Luce 说:“法国人今日思想似乎不能脱离苏俄与美国两个极端理想。中国人恐怕也有点如此吧?”

杜威一直对中国政治和文化抱有浓厚兴趣,时刻关注中国的问题与时局命运,包括中国与美国的关系。用他女儿的话说,中国是杜威仅次于美国最爱的国家。杜威前后留下了几十万字关于中国问题的论述,包括时论、论文、游记、来信答复、解密报告、家信和演讲等各种形式。

https://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2019-04-06/doc-ihvhiewr3491278.shtml">https://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2019...

https://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2019-04-06/doc-ihvhiewr3491278.shtml">https://finance.sina.com.cn/roll/2019...

尽管杜威被自由主义的学生和“新青年”们包围,但他并不完全同意他们对事情的看法。他认为,必须从中国自身的情况出发,去理解中国的历史,而不应该用近代西方的那些政治概念来理解中国的历史状况。他认为,现代中国遇到了一个几乎在所有方面都与自身不同的组织起来的世界,遇到了一种全新的力量。

中国必须改革,但因为有自己长期形成的政治传统和见解,变革将变得长期而艰难。对于美国和远东、中国的关系,他认为美国“在外交和政治上的角色,很大程度上,一直是家长式的”。在许多家庭中,当处于照料和保护下的青少年成长到足以宣誓独立时,就会有危机。在国家这个大家庭中也一样。

20世纪初,中国不少学生赴美留学,其中在哥伦比亚大学受业于杜威的有郭秉文、胡适、陶行知、蒋梦麟、陈鹤琴、张伯苓、刘伯明、郑晓沧、李建勋等人。这些人回国后大力宣传杜威思想,同时用杜威思想积极指导自己的研究和实践。而他们对杜威的思想也有不同程度的继承和发展,因而呈现出不同的特点。

罗志田:胡适是我们四川话所说的“幺儿”,从小没有太多的责任和压力,所以对人生还常有偏于理想的一面;不像鲁迅,因家道中落,“从小康人家而坠入困顿”,在这过程中见识了“世人的真面目”;又身为长子,小则养家糊口,大则重振“家声”,都会感觉到明显的责任。

https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1317727">https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetai...

https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1317727">https://m.thepaper.cn/newsDetai...

胡适在“思想”领域或许有所谓“跟着少年跑”的下意识表现,一向注意随时调整自己与所处时代社会的位置,不给人以落伍的印象;但在学术上却更多是引领而很少迎合,有时甚至有点“独孤求败”的味道(例如坚持了几十年也没有多少人叫好的《水经注》研究)。

胡适1926年访问苏俄时,一个法国人告诉他:“俄国最大的成绩是在短时期中居然改变了一国的倾向,的确成了一个新民族。” 这句话真正打动了胡适,他不由感叹道:“这样子才算是真革命!” 这样的“真革命”,既是胡适愿意接受的,更是他所向往的。

胡适是文学革命的提倡者,也支持家庭革命等一系列社会习俗、礼仪等方面的“革命”。即使对暴力革命,他实际也持一种半可半不可的态度。为了“更好的中国”这一建设性目的,即使付出一定代价,破坏性的手段也是可以接受的,更何况革命还可以是非暴力的。

换言之,革命被认知为一种更多针对未来而非现状的开创性举措,其意义发生了很大的转变。如鲁迅所说:“革命是并非教人死,而是教人活的。” 由于是面向一个可能光明的未来,为许多人带来了乐观的心态、勇气和胆略,使他们可以接受一些他们本来未必欣赏的手段。

胡适的确正式反对过国民党和中共的暴力革命,但为了实现再造文明的根本目标,他似不排除任何手段,因为他知道,“养个孩子还免不了肚痛,何况改造一个国家,何况改造一个文化”!

梁启超在1927年就特别声明:“你们别以为我反对共产,便是赞成资本主义。我反对资本主义比共产党还利害。” 不论他理解的“共产”和“共产党”是否“准确”(当时说“共产党”多泛指国共合作的南方),都能体现出资本主义的不得人心。

在1919年 “五四” 运动前后时期,以胡适为主的“新文化派”和以梅光迪为主的“学衡派”,均在为古老中国寻找新的转机,希望中国文化复兴。但是,他们在接受和选择欧美文化时的不同认识,走上了截然相反的道路。在抗衡中,“学衡派” 一路败北。

http://m.zhishifenzi.com/depth/depth/7689.html">https://m.zhishifenzi.com/depth/dep...

http://m.zhishifenzi.com/depth/depth/7689.html">https://m.zhishifenzi.com/depth/dep...

Hu Shih believed the means to democracy lies in education rather than politics, since democracy as a way of life requires a cultural renewal beyond institutional changes while a problem-centered approach to social change does not preclude radical action, even revolution.

For Dewey, Japan seemed like "a land of reserves and reticence".

He was delighted to find that the social atmosphere in China was much more open and free-flowing.

He was delighted to find that the social atmosphere in China was much more open and free-flowing.

Compared to the huge bulk of literature on Dewey and his voluminous works, studies on his encounter with China are meager.

According to Dewey& #39;s own daughter, his time in China "had a deep and enduring influence upon him."

The encounter between Dewey and China in the 1920s was characterized by ambivalences, uncertainties, and changes on both sides.

Faced with challenges from the West, Chinese intellectuals had initially sought to acquire Western technology and implement Western institutions.

Later, they realized that they had to study the ideas that inform Western development and practice.

Later, they realized that they had to study the ideas that inform Western development and practice.

This meant that Chinese intellectual tradition could no longer remain intact and unimpaired.

On the basis of this realization, the May Fourth intelligentsia savagely attacked their Confucian tradition.

On the basis of this realization, the May Fourth intelligentsia savagely attacked their Confucian tradition.

Early opposition to this anti-traditionalist, iconoclastic trend was feeble.

However, toward theend of the May Fourth period, especially after 1921, traditionalist sentiments, fermented by nationalistic feelings, were beginning to gain momentum.

However, toward theend of the May Fourth period, especially after 1921, traditionalist sentiments, fermented by nationalistic feelings, were beginning to gain momentum.

Dewey correctly characterized the intellectual landscape as vexed by "confusion, uncertainty, mutual criticism and hostility among the various tendencies."

During the two years of his stay, Dewey came into contact with these contending ideologies that made Young China an "ambiguous term", signifying "all kinds of contradictory aspirations".

Although Chinese intellectuals had ambivalent attitudes toward the West, Dewey had his doubts about how the United States should respond to China, or rather, how the United States could help China.

Dewey was trying to understand China and its precarious position in the international world, while Chinese intellectuals were trying to understand Dewey and his position in their ideological battles.

Dewey was eventually able to understand China on its own terms and to propose thoughtful suggestions concerning the United States& #39; responsibility to China.

On the other hand, many Chinese created images of Dewey on their own terms to meet their own needs.

On the other hand, many Chinese created images of Dewey on their own terms to meet their own needs.

Changes in Dewey& #39;s views about China resulted from his own learning and reflection, whereas shifting views of Dewey among Chinese intellectuals reflected their deep-seated frustrations with contemporary events that led either to increasing radicalism or to conservatism.

The dialogue between Dewey and China has been ongoing and tends to be shaped by the historical circumstances and dominant ideologies of each era.

In the 1920s, Chinese opinions of Dewey reflected their own vexed interests in liberalism, neotraditionalism, and Marxism.

In the 1930s and 1940s, as China underwent a series of domestic and international wars, a natural eclipse of interest in Dewey occurred.

In the 1930s and 1940s, as China underwent a series of domestic and international wars, a natural eclipse of interest in Dewey occurred.

Since the establishment of the Communist regime in 1949, the dialogue between Dewey and China took a drastic turn.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Communist government launched a large-scale campaign to purge the pragmatic influences of Hu Shih and Dewey.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Communist government launched a large-scale campaign to purge the pragmatic influences of Hu Shih and Dewey.

During this period, pragmatism was eschewed as an evil influence of Western imperialism and capitalism.

In the 1980s, due to the Reform and Opening-up policy, the dialogue about Dewey was revived.

In the 1980s, due to the Reform and Opening-up policy, the dialogue about Dewey was revived.

Since then, Chinese scholars have started to reevaluate Dewey and pragmatism.

In fact, between 1999 and 2001, three collections of Dewey& #39;s lectures in China were reprinted.

In fact, between 1999 and 2001, three collections of Dewey& #39;s lectures in China were reprinted.

At the turn of the 21st century, China is ready to review and rethink her past.

Before we applaud the resurgence of scholarly interest in Dewey and his influence on Chinese philosophy and modern education, we need to return to the original encounter in the 1920s.

Before we applaud the resurgence of scholarly interest in Dewey and his influence on Chinese philosophy and modern education, we need to return to the original encounter in the 1920s.

Source,

John Dewey in China: To Teach and to Learn

by Jessica Ching-Sze Wang

https://books.google.com/books/about/John_Dewey_in_China.html?id=9Bt0wMdaDkwC">https://books.google.com/books/abo...

John Dewey in China: To Teach and to Learn

by Jessica Ching-Sze Wang

https://books.google.com/books/about/John_Dewey_in_China.html?id=9Bt0wMdaDkwC">https://books.google.com/books/abo...

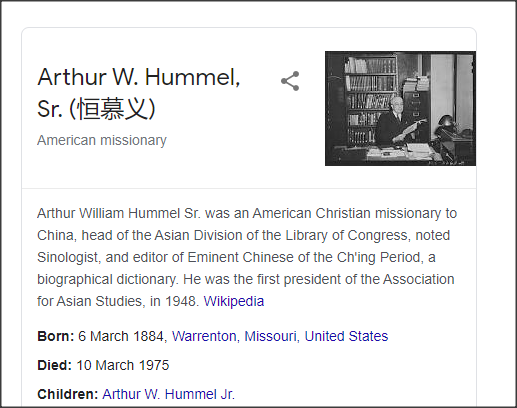

Fascinating article from 1931, on the New Culture Movement in China, by Arthur W. Hummel Sr. (1884 –1975)

#page_scan_tab_contents">https://www.jstor.org/stable/1016538?read-now=1&seq=1 #page_scan_tab_contents">https://www.jstor.org/stable/10...

#page_scan_tab_contents">https://www.jstor.org/stable/1016538?read-now=1&seq=1 #page_scan_tab_contents">https://www.jstor.org/stable/10...

"Chinese minds, trained in Japan, Europe and America, brought their wisdom to bear on this common task of creating a simple, beautiful literary style."

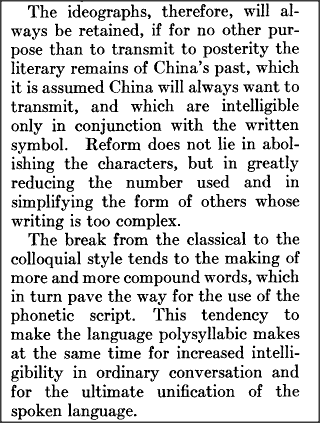

"Reform does not lie in abolishing the characters, but in greatly reducing the number used and in simplifying the form of others whose writing is too complex."

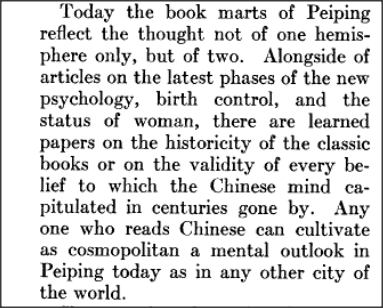

Today the book marts of Peiping (Beijing) reflect the thought not of one hemisphere only, but of two.

"A people who have set their hearts on initiating a new age ... are bound to amputate themselves from a part of their past."

"For recent activities of this realm the Chinese are certainly indebted to the West ... critical traditions of their own upon which they can and do draw."

抗日战争初期,中国国内形势动荡不安,各地藏书散出,恒慕义抓往这一机会,派人大量收集中文图书,出于对日本侵略者的愤恨,有的藏书家甚至分文不要,将珍藏赠与美国国会图书馆。一时间,我国的图书文献资料大量流向大洋彼岸,就连当时国立北平图书馆的善本藏书也不能自保。 http://epaper.gmw.cn/zhdsb/html/2013-11/27/nw.D110000zhdsb_20131127_2-14.htm">https://epaper.gmw.cn/zhdsb/htm...

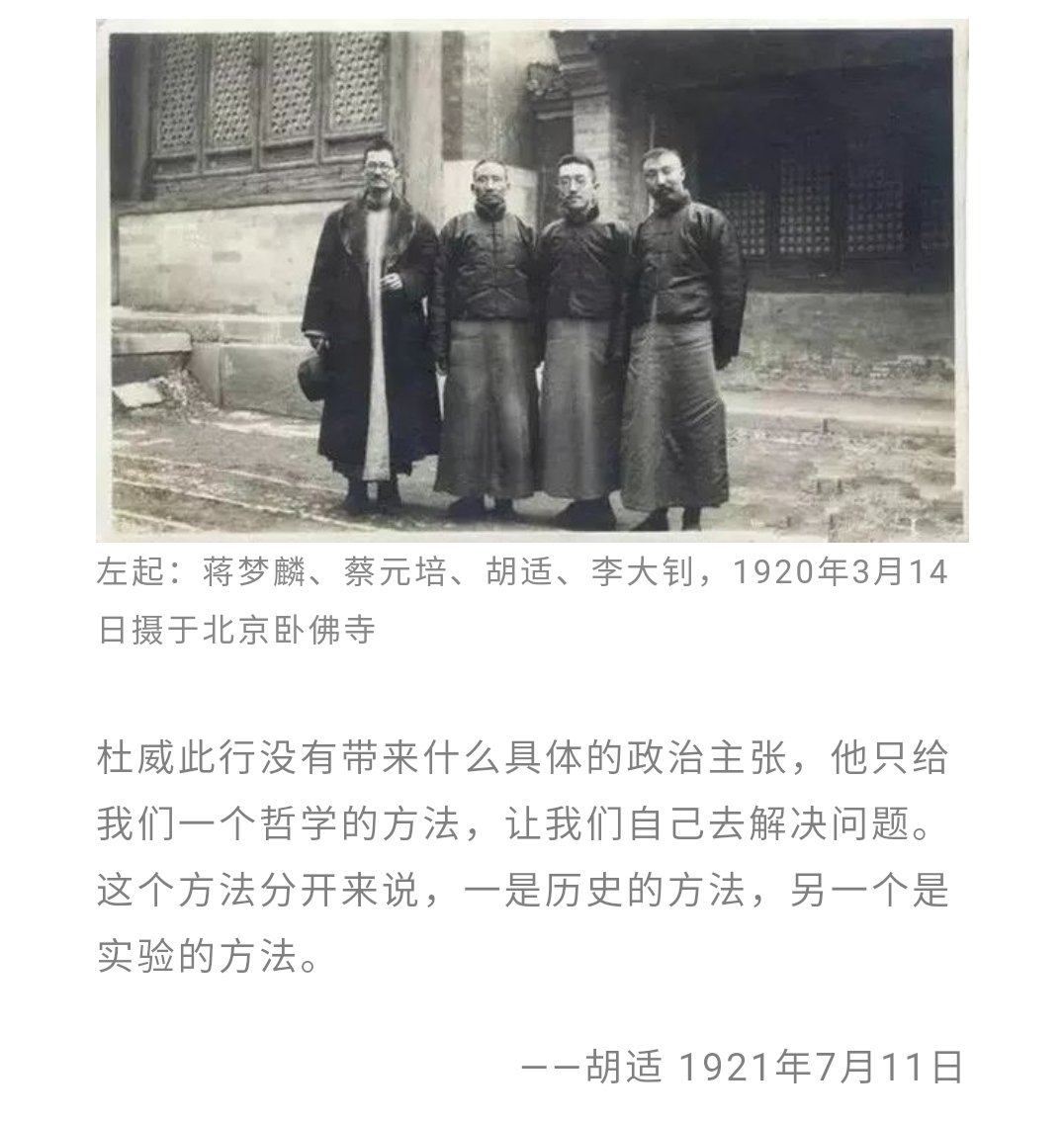

1919年,胡适以学术交流为名,促蔡元培邀杜威来华讲学。杜威的中国之行,是无薪俸的假,所有开销都由邀请方支付。五四运动爆发,蔡元培辞职离京,使北大的承诺不能兑现,杜威在的薪水没有着落,胡适对蔡元培生极大意见,最后由私人组织尚志学会、新学会与和清华学校分担。

杜威在中国一年零三个月,看到原本瞧不上的胡适居然有炙手可热的权势,大为意外,在给女儿信中说胡适“方面太广了,以至于没有太多的时间作哲学,不过他的《中国哲学史》已经付梓。他从事文字、戏剧的改革,翻译易卜生、莫泊桑之外,还是用白话而非文言写诗的第一人。总之,他是中国新文学运动的领袖”。

杜威多数演讲由胡适为之翻译,人们普遍的评价是:杜威的口才并不好,反倒是胡适的翻译,声声入耳,给听众留下难忘印象。胡适还将讲演发于报纸杂志,又汇编成书交北京晨报社出版,在杜威离华前重版十次,每版印数都是一万册。1927年胡适再到纽约,经杜威通融终于拿到博士学位。

最为“胡迷”津津乐道的是,胡适获得36个博士学位,是中国获得博士学位最多的人,“证明国际文化界学术界对胡适的尊重和认可”云云。殊不知荣誉博士的授受,取决于双方的需要。就大学而言,无非想借某人的名声来宣传自己,原是当不得真的。再说,你不跑到门上去招摇,人家怎会凭空授给荣誉博士呢?

按理而论,胡适是应该大搞西方文学翻译,以为中国“树立榜样”的,但他只在年青时译过几个短篇,就收手不干了;按理而论,胡适是应该大写一点白话诗,但是他只在年青时“尝试”了一阵,就收手不干了;按理而论,胡适是不应该对中国“死文学”感兴趣的,但他还没有迈出年青阶段,就开始“整理国故”了。

钱穆说,胡适“是个社会名流式的人物,骨子里不是个读书人”,“世俗之名既大,世俗之事亦困扰之无穷”,“以言以人,两无可取”。唐德刚说:“胡适之那几本破书,实在不值几文。所以我们如果把胡适看成个单纯的学者,那他便一无是处。连做个《水经注》专家,他也当之有愧。”

在半个多世纪里,费正清曾五度来华,亲历了中国的战乱、革命与建设,他结识交往的,包括胡适、傅斯年、梁思成、林徽因、金岳霖、费孝通等中国知识分子。

可以说,费正清的“老友记”几乎囊括了上世纪30年代中国自由主义知识分子的全貌。 https://book.douban.com/review/7390144/ ">https://book.douban.com/review/73...

可以说,费正清的“老友记”几乎囊括了上世纪30年代中国自由主义知识分子的全貌。 https://book.douban.com/review/7390144/ ">https://book.douban.com/review/73...

1932年,费正清第一次见到了胡适,在一封家书中他这样写:“我很惊奇地发现,胡适就是现代的伏尔泰,他坐在我的旁边,帮我递来竹笋和鸭肝。”

1943年10月,费正清与茅盾有过交流,“他留着一撮小八字胡,个头矮小,看起来像个日本人。他很正派,但比较严肃。他说如今每个人都在出版越来越多的翻译作品,因为它们容易通过审查。倘若你靠写文章或短篇小说为生,不小心涉及错误的思想,那么饭碗就不保了。”

在1944年回到华盛顿时,费正清认识到,中国当时的全面改革是必须的,但并不是要改变包罗万象的意识形态,“在中国,最终革命成为唯一的出路,而作为现存革命力量的化身,共产党成为其信仰者生活中类似衣食父母的偶像。”

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter