Physicist Lise Meitner was born #OTD in 1878. She discovered fission in uranium and was the first person to understand both its mechanics and implications.

Image: Atomic Heritage Foundation (photographer unknown)

Image: Atomic Heritage Foundation (photographer unknown)

Meitner’s PhD advisor at the University of Vienna was Ludwig Boltzmann, of S = k ln W fame. In 1907, she went to Berlin to work with Max Planck and Otto Hahn. Meitner& #39;s collaboration with Hahn would last for 30 years.

Meitner handled the physics and Hahn did the chemistry. They had complementary approaches to science — it was a partnership made for discovery. Together, they made several advances related to radioactivity. She also discovered what is commonly called the “Auger Effect” in 1922.

You will not be surprised to learn that Pierre Auger discovered it independently in 1923, a year after Meitner. Other people receiving credit for Meitner& #39;s work will be a theme, so please feel free to refer to it henceforth as the “Meitner effect” or the “Meitner-Auger effect.”

Meitner was Jewish, so in 1938 she was forced to flee Germany. She traveled to Sweden, where she began working in the lab of Manne Siegbahn. Siegbahn was not supportive of women in science, which complicated things for Meitner. But she managed to stay in touch with Hahn.

Meitner and Hahn secretly met in Copenhagen in November 1938, to plan experiments which would extend the "transuranium research” program they began in 1935. In December of 1938, those experiments — carried out by Hahn in Berlin — provided evidence of nuclear fission.

Hahn kept the results hidden from the physicists at his institute in Berlin, protecting his secret collaboration with Meitner. He published them in January 1939. Meitner, along with Otto Frisch, published the physical explanation in February.

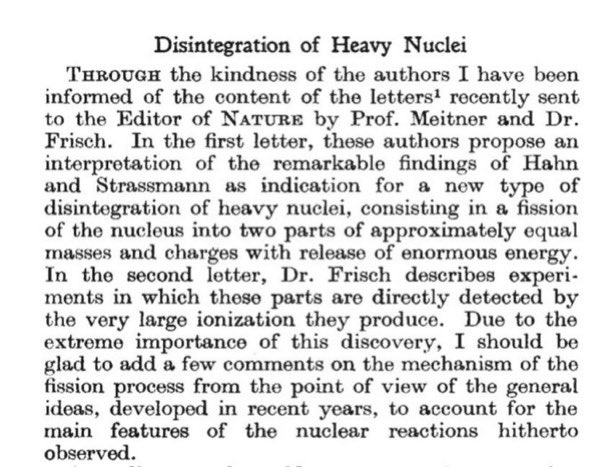

Niels Bohr was also working on fission with Léon Rosenfeld. Bohr knew of Meitner& #39;s work, so when Rosenfeld told the Princeton Physics Journal Club about their collaboration, Bohr quickly wrote a letter to Nature asserting the priority of Meitner & Frisch.

Anyway, Hahn won the Nobel in Chemistry in 1944 for the experiments he devised with Meitner. Meitner was left out. She was nominated for the Nobel several times, but she never won because the Nobel Prize has historically gone out of its way to overlook contributions by women.

And of course anti-Semitism played a huge part. Hahn remained in Berlin throughout the rise of the Nazis. He wasn& #39;t hiding his collaboration with Meitner to protect the results; he was trying to hide his connection to a Jewish collaborator whose insights made his work possible.

In the eyes of many of her colleagues, Meitner was a woman and a Jew first, and a superior scientist second. Her career suffered for it.

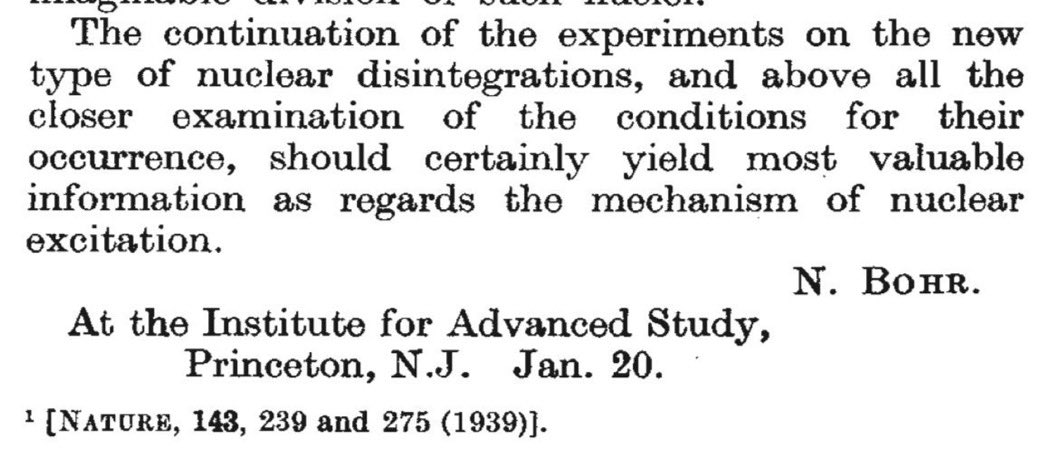

Meitner& #39;s work on fission set off a chain of events which led to the Manhattan Project and the atomic bomb. She came to the US, but refused an offer to work at Los Alamos. “I will have nothing to do with a bomb!”

Ref: Ruth Lewin Sime "Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics,” p. 305

Ref: Ruth Lewin Sime "Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics,” p. 305

Nevertheless, when she toured the US in 1946 she was given the Einstein celebrity treatment. The media tried to portray her as escaping Germany with the "bomb in her purse," but Meitner was not having it. (Sime, p. 332)

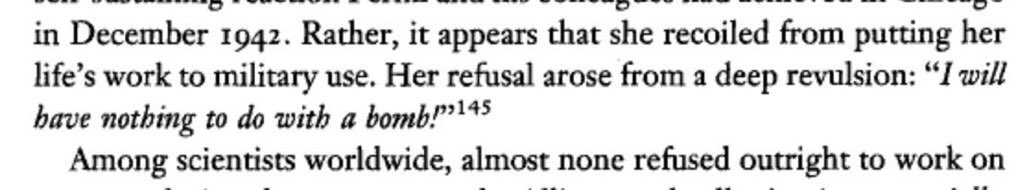

Here is Meitner talking with students during a 1959 visit to Bryn Mawr.

Image: Heka Davis, AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Image: Heka Davis, AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Physics Today Collection

Meitner returned to Sweden after the war, where she became the head of her own laboratory funded by the Swedish Atomic Energy Commission. In 1960 she settled down in Cambridge, close to relatives.

Lise Meitner passed away in 1968. Her nephew and collaborator Otto Frisch composed her epitaph: "Lise Meitner: a physicist who never lost her humanity"

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter