2/

Imagine that you& #39;ve just started an insurance company -- XYZ Corp.

XYZ is based in Florida, and it sells auto insurance.

By relentlessly pestering your family members and friends, you manage to convince 100 people to switch to XYZ from their current insurance provider.

Imagine that you& #39;ve just started an insurance company -- XYZ Corp.

XYZ is based in Florida, and it sells auto insurance.

By relentlessly pestering your family members and friends, you manage to convince 100 people to switch to XYZ from their current insurance provider.

3/

At the start of each year, your customers pay you an annual premium.

In exchange for this premium, you take on some risk.

If a customer& #39;s car is damaged during the year -- for example, due to an accident -- you have to pay to fix it.

At the start of each year, your customers pay you an annual premium.

In exchange for this premium, you take on some risk.

If a customer& #39;s car is damaged during the year -- for example, due to an accident -- you have to pay to fix it.

4/

Real-world insurance policies of course have a range of loss exposures, deductibles, etc.

But for this thread, let& #39;s simplify things a bit.

Let& #39;s say, in any year, there are only 2 possibilities for each car covered by XYZ Corp. -- either the car is fine, or it is totaled.

Real-world insurance policies of course have a range of loss exposures, deductibles, etc.

But for this thread, let& #39;s simplify things a bit.

Let& #39;s say, in any year, there are only 2 possibilities for each car covered by XYZ Corp. -- either the car is fine, or it is totaled.

5/

If a car is fine, great! XYZ Corp. gets to pocket the annual premium.

But if a car is totaled, XYZ Corp. has to pay the customer $10K.

If a car is fine, great! XYZ Corp. gets to pocket the annual premium.

But if a car is totaled, XYZ Corp. has to pay the customer $10K.

6/

You estimate that the probability of any one car being totaled in any one year is about 14.5%.

The question now is: what premium should you charge your customers?

You estimate that the probability of any one car being totaled in any one year is about 14.5%.

The question now is: what premium should you charge your customers?

7/

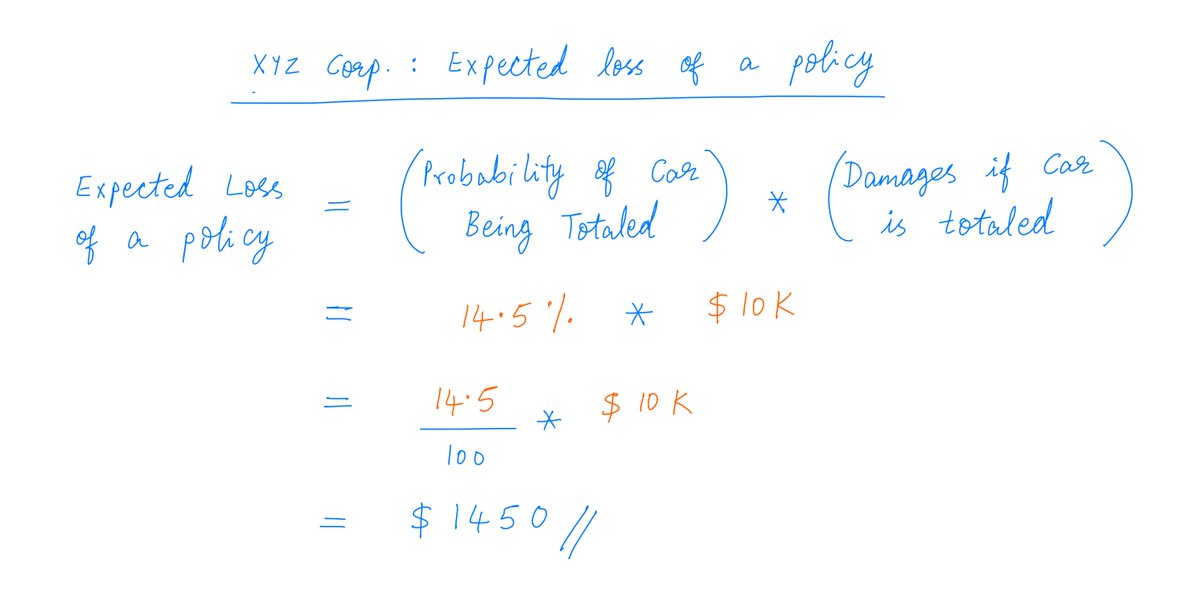

One way to answer this is to calculate the *expected* loss of a policy.

We know each policy has a 14.5% chance of a $10K loss, and an 85.5% chance of a $0 loss.

So the expected loss works out to $1450:

One way to answer this is to calculate the *expected* loss of a policy.

We know each policy has a 14.5% chance of a $10K loss, and an 85.5% chance of a $0 loss.

So the expected loss works out to $1450:

8/

Given this expected $1450 loss, let& #39;s say you set the annual premium at $1600.

This gives you a $150 expected underwriting profit per policy.

That& #39;s ($150 per policy) * (100 policies) = $15K in expected underwriting profit -- per year -- for XYZ Corp. Not bad.

Given this expected $1450 loss, let& #39;s say you set the annual premium at $1600.

This gives you a $150 expected underwriting profit per policy.

That& #39;s ($150 per policy) * (100 policies) = $15K in expected underwriting profit -- per year -- for XYZ Corp. Not bad.

9/

When evaluating such a policy portfolio, it& #39;s generally a good idea to ask: what will it take to push the portfolio into the red?

In this case, you collect ($1600 per policy) * (100 policies) = $160K in annual premiums.

And you have to pay out $10K for every totaled car.

When evaluating such a policy portfolio, it& #39;s generally a good idea to ask: what will it take to push the portfolio into the red?

In this case, you collect ($1600 per policy) * (100 policies) = $160K in annual premiums.

And you have to pay out $10K for every totaled car.

10/

This means you can handle up to 16 totaled cars in any one year without suffering a loss.

You incur a *loss* in any particular year only if *17 or more* cars are totaled that year.

What are the chances of that?

This means you can handle up to 16 totaled cars in any one year without suffering a loss.

You incur a *loss* in any particular year only if *17 or more* cars are totaled that year.

What are the chances of that?

11/

Well, if each car& #39;s probability of being totaled is independent of all the other cars, then your chances of an underwriting loss in any 1 year are about 27.74%.

That is, you have a ~72.26% chance of breaking even or realizing an underwriting profit in any 1 year.

Well, if each car& #39;s probability of being totaled is independent of all the other cars, then your chances of an underwriting loss in any 1 year are about 27.74%.

That is, you have a ~72.26% chance of breaking even or realizing an underwriting profit in any 1 year.

12/

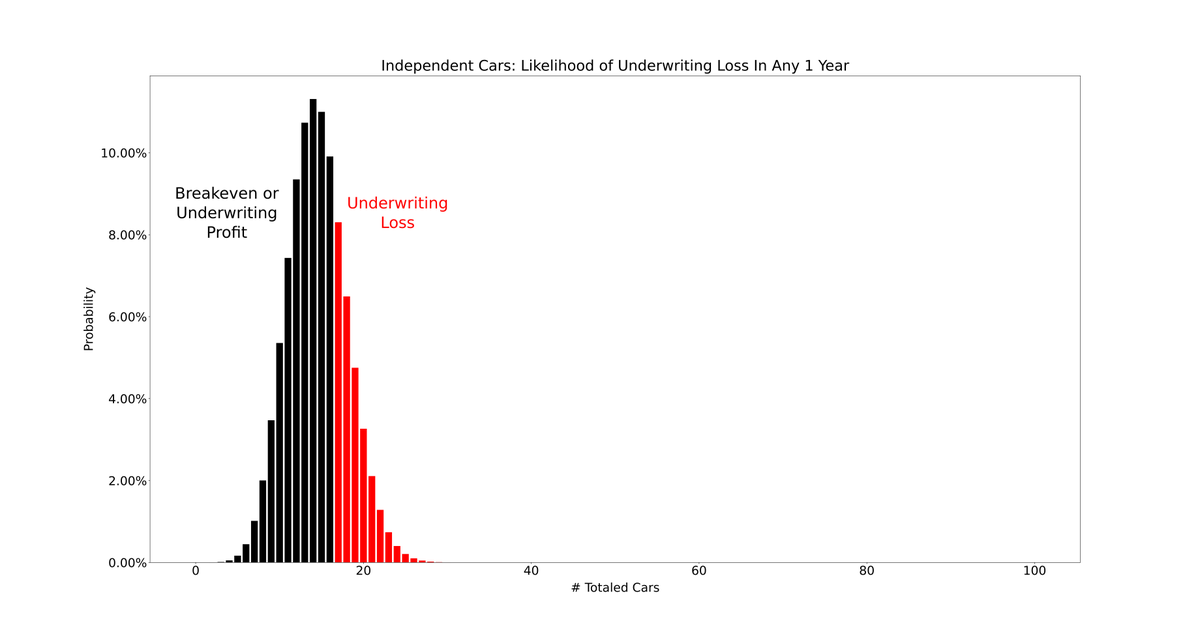

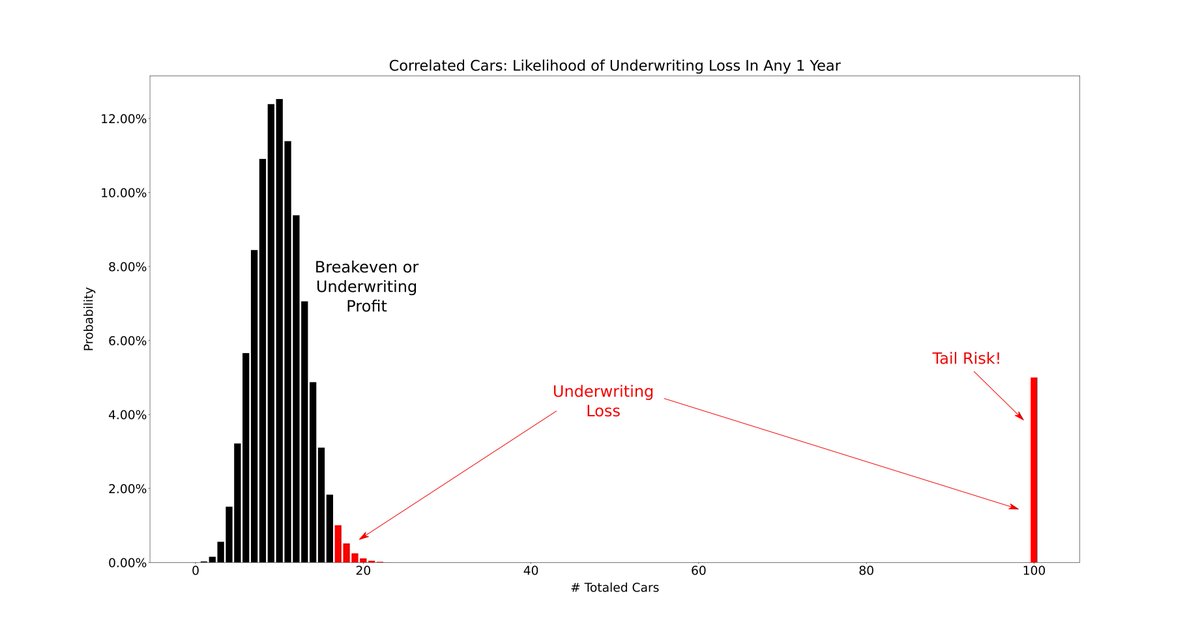

This picture shows all the possible outcomes and their respective probabilities.

Best case: 0 totaled cars

Worst case: 100 totaled cars

Breakeven or underwriting profit: <= 16 totaled cars

Underwriting loss: >= 17 totaled cars

This picture shows all the possible outcomes and their respective probabilities.

Best case: 0 totaled cars

Worst case: 100 totaled cars

Breakeven or underwriting profit: <= 16 totaled cars

Underwriting loss: >= 17 totaled cars

13/

Charging a $1600 premium is like placing a bet with odds of 72.26 to 27.74 in your favor.

Over time, you cannot lose.

If you stay in business long enough, your likelihood of accumulating a loss goes to zero -- *provided* your premium exceeds the $1450 expected loss.

Charging a $1600 premium is like placing a bet with odds of 72.26 to 27.74 in your favor.

Over time, you cannot lose.

If you stay in business long enough, your likelihood of accumulating a loss goes to zero -- *provided* your premium exceeds the $1450 expected loss.

14/

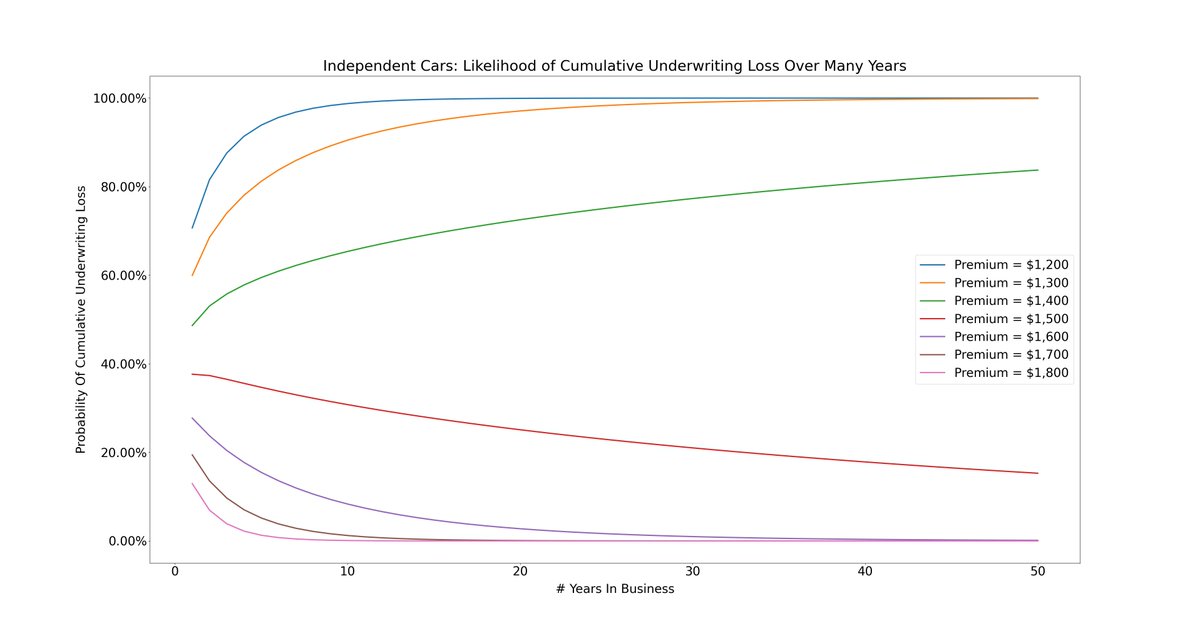

For example, with a $1600 premium, there& #39;s only a 2.76% chance that you& #39;d accumulate a loss if you stayed in business for 20 years.

But note this: if your premium is *lower* than the $1450 expected loss, then your probability of accumulating a loss grows to 100% over time.

For example, with a $1600 premium, there& #39;s only a 2.76% chance that you& #39;d accumulate a loss if you stayed in business for 20 years.

But note this: if your premium is *lower* than the $1450 expected loss, then your probability of accumulating a loss grows to 100% over time.

15/

So, charging a $1600 premium seems reasonable.

But remember: this all hinges on our *independence* assumption. We assumed that the probability of one car being totaled was independent of all the other cars.

So, charging a $1600 premium seems reasonable.

But remember: this all hinges on our *independence* assumption. We assumed that the probability of one car being totaled was independent of all the other cars.

16/

Unfortunately, in a place like Florida, this can be a bad assumption.

Why? Because hurricanes.

If a hurricane hits, let& #39;s say all the 100 cars covered by XYZ Corp. will be totaled -- in one shot.

Unfortunately, in a place like Florida, this can be a bad assumption.

Why? Because hurricanes.

If a hurricane hits, let& #39;s say all the 100 cars covered by XYZ Corp. will be totaled -- in one shot.

17/

That means, from a risk standpoint, our 100 insurance policies are *significantly* correlated.

This correlation creates "tail risk".

To understand tail risk, let& #39;s break down the risk of a car being totaled into 2 "sub-risks" -- "accident risk" and "hurricane risk".

That means, from a risk standpoint, our 100 insurance policies are *significantly* correlated.

This correlation creates "tail risk".

To understand tail risk, let& #39;s break down the risk of a car being totaled into 2 "sub-risks" -- "accident risk" and "hurricane risk".

18/

Let& #39;s say there& #39;s a 10% chance that a car will meet with an accident in any 1 year.

This "accident risk" is *independent*.

After all, in a large city, the chances of any 1 car meeting with an accident are pretty much independent of any other car.

Let& #39;s say there& #39;s a 10% chance that a car will meet with an accident in any 1 year.

This "accident risk" is *independent*.

After all, in a large city, the chances of any 1 car meeting with an accident are pretty much independent of any other car.

19/

But in addition to "accident risk", we also have "hurricane risk".

Let& #39;s say, in any 1 year, there& #39;s a 5% chance of a hurricane hitting the city.

In this case, the hurricane will total all the 100 cars.

Clearly, this is *not* an independent risk.

It& #39;s *correlated* risk.

But in addition to "accident risk", we also have "hurricane risk".

Let& #39;s say, in any 1 year, there& #39;s a 5% chance of a hurricane hitting the city.

In this case, the hurricane will total all the 100 cars.

Clearly, this is *not* an independent risk.

It& #39;s *correlated* risk.

20/

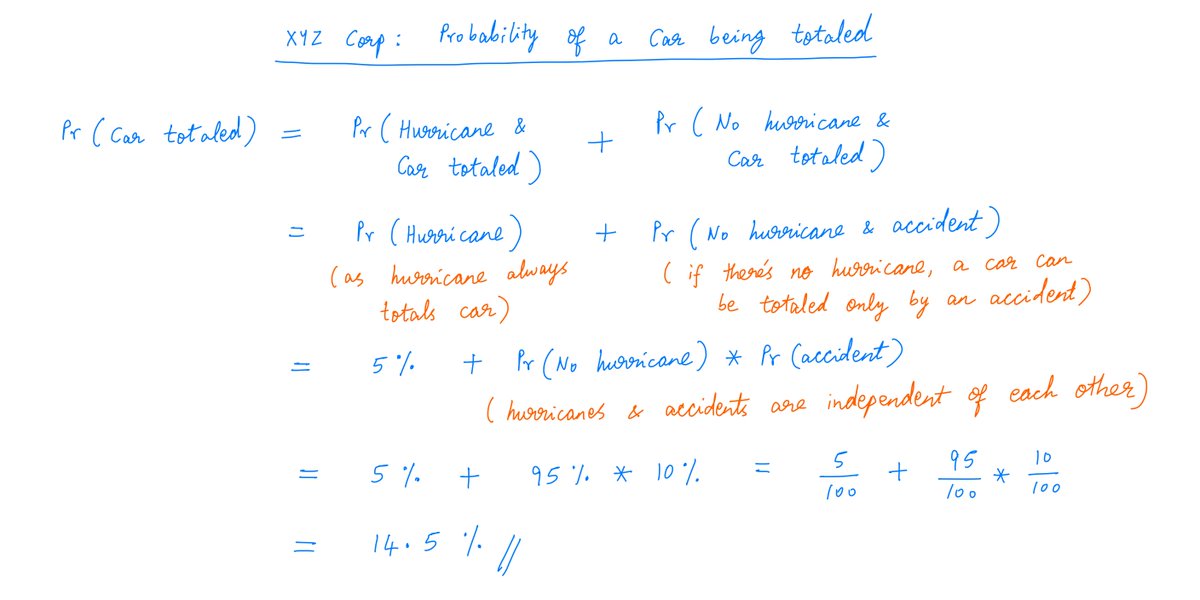

Note that the chance of a car being totaled in any 1 year is still the same 14.5%. And so, the expected loss of a policy is still the same $1450.

We& #39;ve just broken this down into an "accident" part and a "hurricane" part.

Calculations:

Note that the chance of a car being totaled in any 1 year is still the same 14.5%. And so, the expected loss of a policy is still the same $1450.

We& #39;ve just broken this down into an "accident" part and a "hurricane" part.

Calculations:

21/

So, here& #39;s an interesting question.

The expected loss of any 1 policy is still the same $1450.

So, if we charge the same $1600 premium, what& #39;s the problem?

We should still be covered because our premium exceeds the policy& #39;s expected loss, right?

So, here& #39;s an interesting question.

The expected loss of any 1 policy is still the same $1450.

So, if we charge the same $1600 premium, what& #39;s the problem?

We should still be covered because our premium exceeds the policy& #39;s expected loss, right?

22/

Theoretically, that is correct.

But practically, we now we have to grapple with an additional problem: tail risk.

To see *why* tail risk is a problem, let& #39;s again plot all possible outcomes and their respective probabilities in any 1 year:

Theoretically, that is correct.

But practically, we now we have to grapple with an additional problem: tail risk.

To see *why* tail risk is a problem, let& #39;s again plot all possible outcomes and their respective probabilities in any 1 year:

23/

In this case, the chance of an underwriting loss in any 1 year is *only* 6.96% -- as opposed to the 27.74% we had earlier.

In other words, charging a $1600 premium is like placing a bet with odds of 93.04% to 6.96% in our favor!

What could possibly go wrong!

In this case, the chance of an underwriting loss in any 1 year is *only* 6.96% -- as opposed to the 27.74% we had earlier.

In other words, charging a $1600 premium is like placing a bet with odds of 93.04% to 6.96% in our favor!

What could possibly go wrong!

24/

I& #39;ll tell you.

In the 6.96% of the time the bet goes against us -- or, to be more precise, the 5% of the time the bet goes against us *because of a hurricane* -- we& #39;re taken to the cleaners.

In such years, our losses will be so heavy they& #39;ll negate many years of gains.

I& #39;ll tell you.

In the 6.96% of the time the bet goes against us -- or, to be more precise, the 5% of the time the bet goes against us *because of a hurricane* -- we& #39;re taken to the cleaners.

In such years, our losses will be so heavy they& #39;ll negate many years of gains.

25/

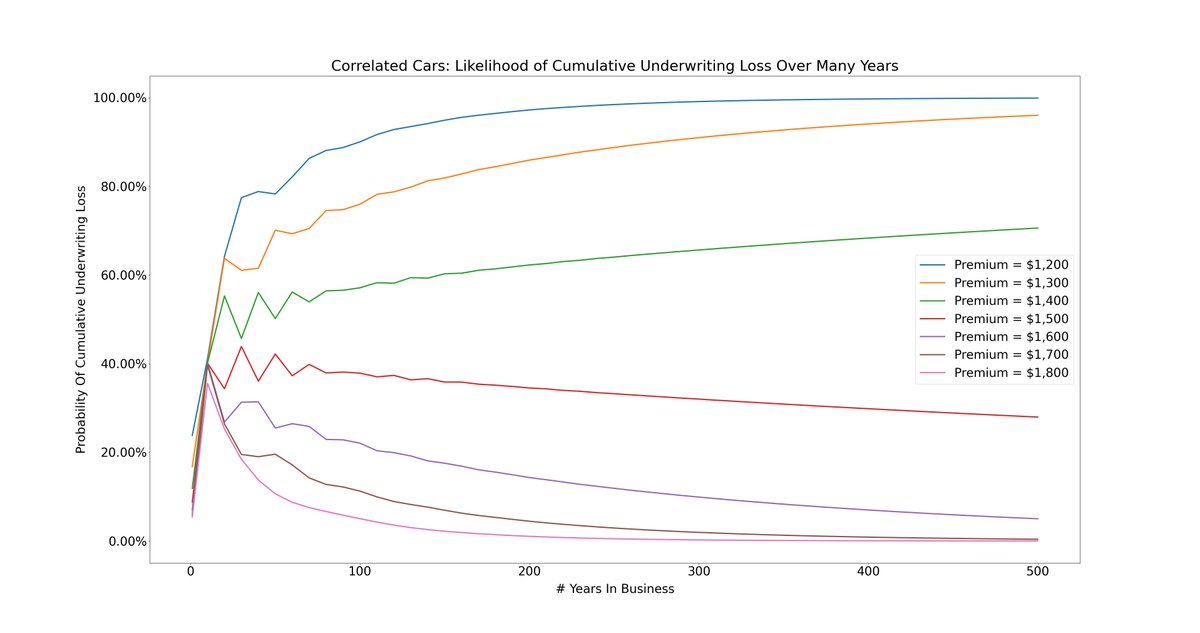

We may get lucky with a few hurricane free years.

But eventually, if we stay in business long enough, a hurricane *will* hit. That& #39;s the tail risk.

Here& #39;s a plot showing the probability of accumulating a loss over many years in business:

We may get lucky with a few hurricane free years.

But eventually, if we stay in business long enough, a hurricane *will* hit. That& #39;s the tail risk.

Here& #39;s a plot showing the probability of accumulating a loss over many years in business:

26/

Note: that& #39;s a 500 year plot!

The same observations apply. Premiums that exceed the $1450 expected loss are *eventually* guaranteed to produce profits.

But *convergence* to that eventuality can take centuries!

That, unfortunately, is how tail risk rolls.

Note: that& #39;s a 500 year plot!

The same observations apply. Premiums that exceed the $1450 expected loss are *eventually* guaranteed to produce profits.

But *convergence* to that eventuality can take centuries!

That, unfortunately, is how tail risk rolls.

27/

For example, at our $1600 premium, even after 20 years in business, there& #39;s still a 26.83% chance of an accumulated loss.

Even after 500 years in business, there& #39;s a 5.02% chance.

For example, at our $1600 premium, even after 20 years in business, there& #39;s still a 26.83% chance of an accumulated loss.

Even after 500 years in business, there& #39;s a 5.02% chance.

28/

What if we want to get the 20-year loss likelihood under 3% -- comparable to the respectable 2.76% we had earlier?

In that case, there& #39;s only 1 course open to us. We have to raise the premium by about 50% -- from $1600 to about $2400.

What if we want to get the 20-year loss likelihood under 3% -- comparable to the respectable 2.76% we had earlier?

In that case, there& #39;s only 1 course open to us. We have to raise the premium by about 50% -- from $1600 to about $2400.

29/

Key lesson: when deciding whether to bet on a probability distribution, don& #39;t look at just its *expected value*.

Understand the whole distribution -- including its tail outcomes, their probabilities, and the consequences if such outcomes occur. Because one day, they will.

Key lesson: when deciding whether to bet on a probability distribution, don& #39;t look at just its *expected value*.

Understand the whole distribution -- including its tail outcomes, their probabilities, and the consequences if such outcomes occur. Because one day, they will.

30/

Many investment portfolios contain meaningful tail risk.

Usually, this is because of correlations.

If *many* portfolio companies are exposed to the *same* risk factor (like the value of a particular currency) -- that& #39;s exactly like many cars exposed to the same hurricane.

Many investment portfolios contain meaningful tail risk.

Usually, this is because of correlations.

If *many* portfolio companies are exposed to the *same* risk factor (like the value of a particular currency) -- that& #39;s exactly like many cars exposed to the same hurricane.

31/

Some tail risks are easy to eliminate -- once we know some probability basics.

For example, the Kelly Criterion teaches us never to go all in on a bet if there& #39;s a chance of total ruin -- even if it& #39;s a 99 to 1 shot.

For more: https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1264622958468726785">https://twitter.com/10kdiver/...

Some tail risks are easy to eliminate -- once we know some probability basics.

For example, the Kelly Criterion teaches us never to go all in on a bet if there& #39;s a chance of total ruin -- even if it& #39;s a 99 to 1 shot.

For more: https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1264622958468726785">https://twitter.com/10kdiver/...

32/

But often, tail risks are unavoidable.

Whenever we get in a car or on a plane, we assume some tail risk.

The best we can do is to be aware of it, and if possible anticipate and prepare accordingly.

But often, tail risks are unavoidable.

Whenever we get in a car or on a plane, we assume some tail risk.

The best we can do is to be aware of it, and if possible anticipate and prepare accordingly.

33/

In investing, that usually means either hedging or diversifying.

For example, if we put a lot of money on one stock that has a small chance of going to zero, it may be a good idea to cap our downside by buying put options. This is hedging.

For more: https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1276905920929206272">https://twitter.com/10kdiver/...

In investing, that usually means either hedging or diversifying.

For example, if we put a lot of money on one stock that has a small chance of going to zero, it may be a good idea to cap our downside by buying put options. This is hedging.

For more: https://twitter.com/10kdiver/status/1276905920929206272">https://twitter.com/10kdiver/...

34/

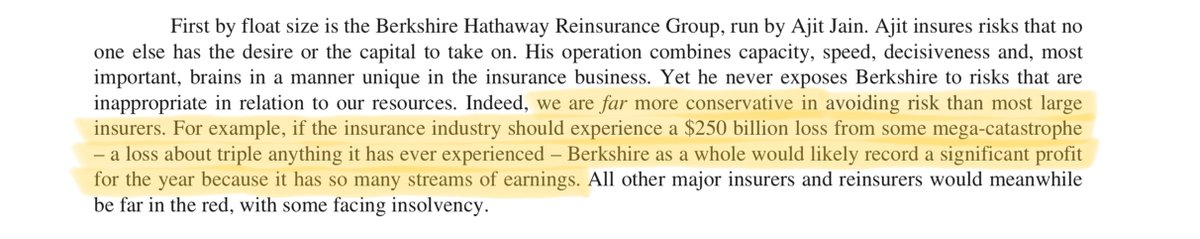

Diversifying can also dramatically minimize tail risk.

For example, Buffett often attributes Berkshire& #39;s ability to write huge insurance policies to its many diversified earnings streams.

From his 2012 letter:

Diversifying can also dramatically minimize tail risk.

For example, Buffett often attributes Berkshire& #39;s ability to write huge insurance policies to its many diversified earnings streams.

From his 2012 letter:

35/

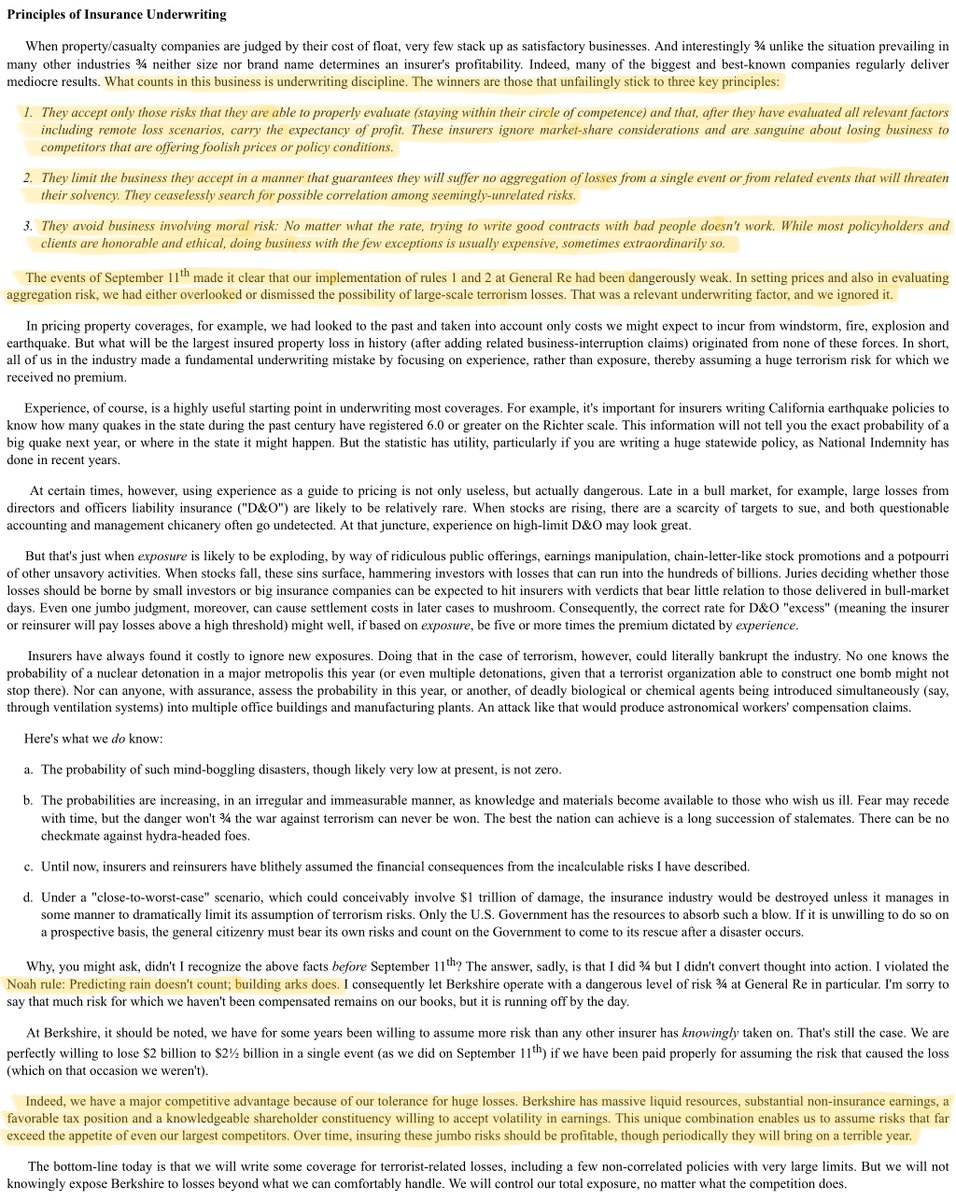

I also recommend reading Buffett& #39;s 2001 letter, which delves into how insurers should think about risk aggregation and correlated tail risks across a policy portfolio.

For some reason, in subsequent letters, Buffett removed the part about correlations. I wish he& #39;d kept it.

I also recommend reading Buffett& #39;s 2001 letter, which delves into how insurers should think about risk aggregation and correlated tail risks across a policy portfolio.

For some reason, in subsequent letters, Buffett removed the part about correlations. I wish he& #39;d kept it.

36/

@nntaleb& #39;s books (Fooled By Randomness, The Black Swan) are also full of interesting lessons on understanding tail risk and minimizing one& #39;s exposure to it.

@nntaleb& #39;s books (Fooled By Randomness, The Black Swan) are also full of interesting lessons on understanding tail risk and minimizing one& #39;s exposure to it.

37/

@HowardMarksBook has also written some beautiful memos on uncertainty and risk in general, and on tail risk in particular.

I think this memo from 2014 is particularly illuminating: https://www.oaktreecapital.com/docs/default-source/memos/2014-09-03-risk-revisited.pdf">https://www.oaktreecapital.com/docs/defa...

@HowardMarksBook has also written some beautiful memos on uncertainty and risk in general, and on tail risk in particular.

I think this memo from 2014 is particularly illuminating: https://www.oaktreecapital.com/docs/default-source/memos/2014-09-03-risk-revisited.pdf">https://www.oaktreecapital.com/docs/defa...

38/

If you& #39;d rather listen to @HowardMarksBook, this episode of The Knowledge Project by @ShaneAParrish has you covered.

Here, @HowardMarksBook beautifully describes why we should go beyond the expected value -- and consider tail risks as well: https://fs.blog/knowledge-project/howard-marks/">https://fs.blog/knowledge...

If you& #39;d rather listen to @HowardMarksBook, this episode of The Knowledge Project by @ShaneAParrish has you covered.

Here, @HowardMarksBook beautifully describes why we should go beyond the expected value -- and consider tail risks as well: https://fs.blog/knowledge-project/howard-marks/">https://fs.blog/knowledge...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter