A thread on blind judging and why I don’t like it: An article was recently published criticising a new procedure around blind judging that we’ve begun developing at Overland. I was aware of the criticism as the author of the piece sent the bulk of their points to us earlier.

We decided not to individually respond, but worked with an AusLit elder to commission an essay on prizes and judging, which will be published in our summer edition. These tweets are not my response to the article, but rather my statement on why we’re working on a new procedure.

Blind judging is a beneficial but deeply flawed process, for a multitude of reasons. Removing a name from a submission doesn’t conceal style, and it doesn’t place a sensitive text in a cultural, social, or political vacuum.

In a relatively small literary space such as Australia, blind judging prizes mostly serves to resist nepotism. In a field such as poetry, it’s hard to judge a prize without knowing at least a few of the entrants. Removing identifiers doesn’t prevent nepotism, but probably helps.

In my career I’ve judged a bunch of prizes across fiction, poetry, essay and performance. In every blind prize I’ve had the same reoccurring issue arise regarding works which I feel seek to take advantage of the goodwill assumed in blind judging processes.

I’ve spoken about this to many other judges and writers, and I’ve heard many similar accounts of works which style themselves directly in the voice, style, and often culturally specific language/literary techniques of an oppressed group.

The argument should be that the best piece wins, the author is dead and we should simply judge by the quality of work. It’s a pretty idea but it not only neglects the broader context of why blind judging was developed, it is also naive to the nuances judges are expected to bring.

A disenchanted and bitter writer who assumes prizes are judged by identity and not quality would look to the changing faces of shortlists and assume tokenism, pity or virtue signalling from the judges. Any writer of diversity has had that accusation flung against them many times.

While I try to give respect to everyone in the horrendously underfunded field of literature, I’m not going to lie that I do feel like this is an accusation that often serves to ever so thinly veil more aggressive acts of racism.

Blind judging is a faulty process, but can do something to challenge these accusations. But it doesn’t protect writers from marginalised communities, especially when they know they will face scrutiny from a literary community so ready to undermine anything that unsettled it.

I don’t know anyone who awarded a prize because of identity, but I know on many occasions work has not been awarded because the judges couldn’t be confident about the nature of a piece.

There’s no such thing as objective literary quality. When deciding between a range of excellent works, it never comes to “well what’s better?”

They’re questions of what is fresh and innovative, what is formally the most competent, what spoke to me most directly, what changed the way I thought about this topic, what should a wider audience read, what surprised me, what was brave, and so many other considerations.

Many of these considerations are what lead judges towards pieces exploring experiences and perspectives from marginalised communities. Unfortunately, it’s also what leads some writers to appropriate marginalised stories and voices.

Whether they do it to prove a point, to win a prize, or to genuinely explore the fullest potential of their own abilities, and whether you think every writer has the right to tell every story or not, the debate endlessly reaffirms the same damaging logic:

The notion that some lives make great content if you’re good enough at what you do to pull it off. This argument in the face of long histories of erasure, violence and exploitation.

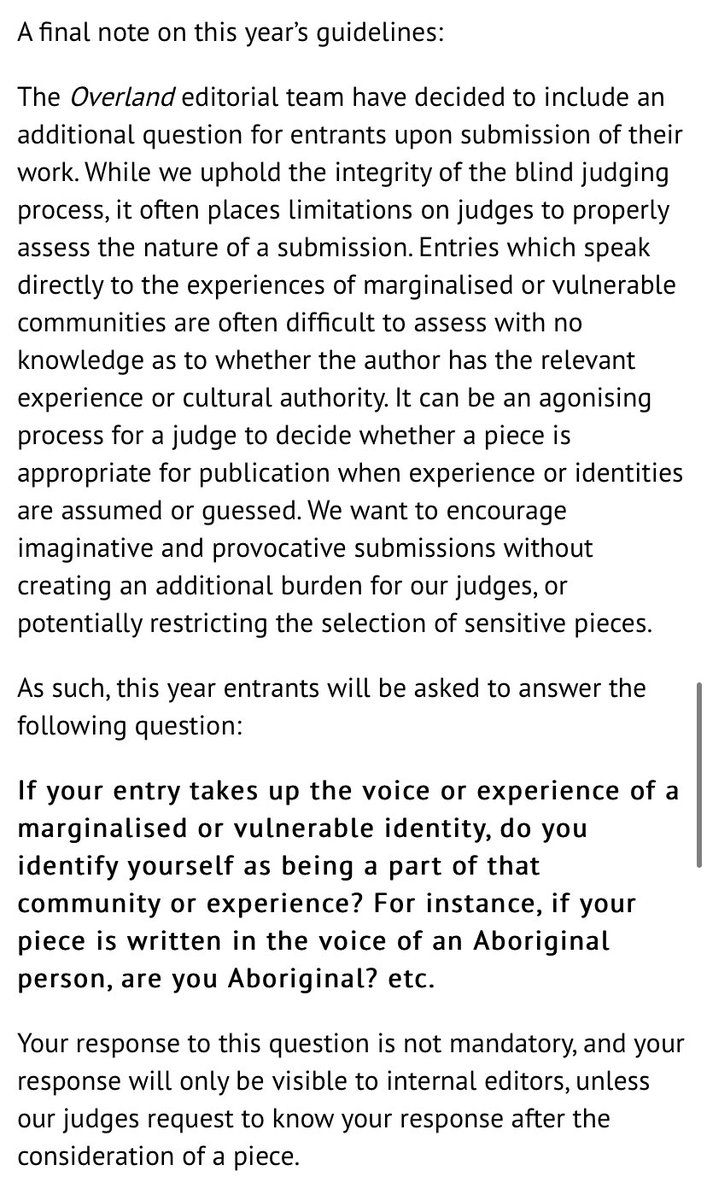

This year, we tried to do something a little different in our blind judging process. Next year we’ll try something different again. Hopefully this can be an industry conversation, and not just a solo experiment.

Time and time again I have seen brave and powerful pieces rejected by blind judging processes because judges didn’t have confidence in a system that makes possible appropriation and posturing. This voluntary question is an attempt to get people to think about what they submit.

Out of the hundreds of submissions we’ve already received, I think a very small handful of people have chosen to answer it. That’s totally fine! We wanted to try something new to see if it could make any sort of impact on an imperfect process.

We absolutely welcome criticism, suggestions, or any form of engagement with this process. But we collectively need to admit to ourselves that this process isn’t complete, and these procedures are too easy to exploit.

I absolutely do believe that writers of marginality are the ones most disadvantaged by blind judging, but I welcome other forms of engagement. This was my attempt to change something I had witnessed to be harmful.

I would also add: I never do anything without consultation. This policy has been in discussion well before I ever applied for this job. We didn’t announce this change because we have commissioned someone we deeply respect to write an article on the topic and encourage dialogue.

The piece responding to this procedure structured its argument as a rejection of the essentialist argument that you can only write what you’ve lived through. We didn’t say that in the implementation of this question. We work with a range of judges who will hold different views.

When we select a judging panel, we look for diversity of approach to create balance. We could have explained why we wanted that question, and give more detail on how it might be used in the process. However I did want to normalise this as much as possible. I didn’t want a stunt.

The question isn’t there to disqualify entries but to provide context where a piece might engage with highly sensitive topics. Specifically, it arose out of writers explicitly black-facing our blind judging process. We wanted it there to help our judges when these scenarios arise

Further, answers to this question will not be revealed to judges unless they request it due to any serious concerns being raised in the judging process. It’s not there for diversity bingo or to discourage imagination.

We published a piece only a few weeks ago discouraging the bottlenecking of ‘diverse’ writers into performing their diversity for mainstream consumption. We don’t support tokenism, and we don’t feel that this procedure does either.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter