One environmental justice issue I& #39;ve been thinking about a lot lately is the impacts dams have had on native communities.

The Missouri River is an excellent example. In the & #39;40s, the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation were locked in a vicious competition to & #39;claim& #39; river systems for their dam builders.

USACE, whose mandate was flood control rather than river development, traditionally worked in the east and Reclamation in the West.

However, the USACE was allowed to provide farmers w/ free water (vs BoR& #39;s heavily subsidized, but still priced, water) and was interested in empire building, so it expanded west, w/ some success, into BoR territory.

I really am not understating things when I say that these were fights: the two agencies were constantly jostling for the upper hand in the executive branch, and would marshal support from congressional allies to gain them control of basins.

One of the river systems that became a flashpoint for this battle of bureaucracies was the Missouri. Undammed as of midcentury, both agencies came up with grandiose visions for the basin

(Incentives at that time were such that more dams = better, because then everyone& #39;s district/state gets a dam and related construction/cheap irrigation water largesse)

The USACE, which had been initially selected to develop the Missouri, developed the Pick plan. The BoR, not to be outdone, developed the Sloan Plan. Between them, they had proposed building 113 dams across the entire river system.

Rather than going with one plan or another, electeds chose to -- wait for it -- combine the two. This was, by and large, simply a combination. 107/113 projects remained.

There are many criticisms to be made on a purely environmental and economic basis of a dam plan that extensive (most dam projects had benefit/cost ratios <<1), but I wanna focus on the environmental justice impacts of this scheme.

Though the plan studiously avoided flooding white towns of any size (notice how Pierre SD, Bismarck ND, etc are along free-flowing bits of the river), it had a huge impact on native reservation lands.

Much of the area proposed to be flooded under Pick-Sloan was rich valley land on reservations, lands central to (agri)culture on the reservations.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pick%E2%80%93Sloan_Missouri_Basin_Program#/media/File:Map_Pick%E2%80%93Sloan_Missouri_Basin_Program.png">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pick...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pick%E2%80%93Sloan_Missouri_Basin_Program#/media/File:Map_Pick%E2%80%93Sloan_Missouri_Basin_Program.png">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pick...

To attain rights to those valley lands, the US ran roughshod over native sovereignty. Not only did they abrogate native rights to determine what happened on their land (which is all too common in history), but they refused to grant impacted communities any real compensation

The original settlement for the project had included some bare-bones givebacks to somewhat ameliorate at least the material impacts of the valley& #39;s loss: at-cost electricity, irrigation water, grazing rights, etc.

Through some particularly heinous maneuvering on the part of the USACE in congress, those rights were denied, and native communities were forbidden from so much as taking their cattle to drink at the reservoir, or removing the trees from the soon-to-be-flooded land.

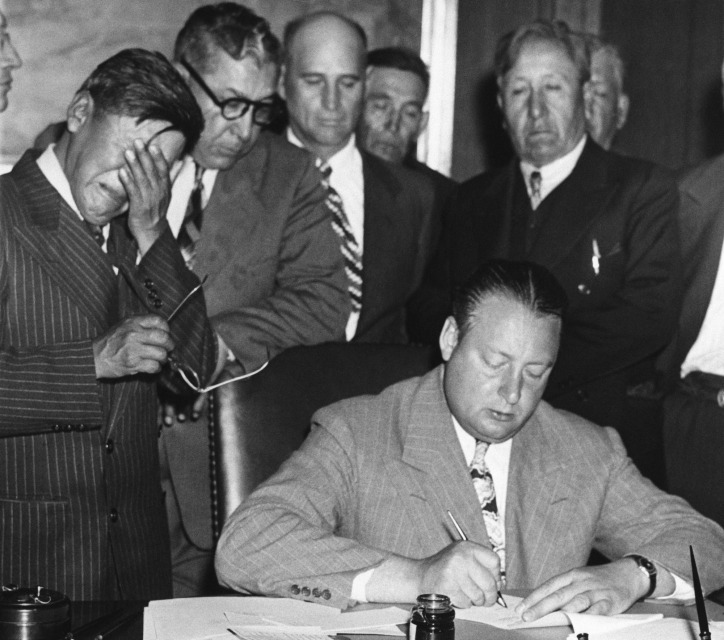

I think I posted this when I discussed this history on my streetview journey, but this is a photo that has really stuck with me over the years. We& #39;re looking at the signing of the & #39;agreement& #39; to build these dams; the man at left is the representative of the Fort Berthold Tribes.

And...so it was. The dams got built, native communities suffered, and the rest of America moved on. To this day, those communities are fighting for fair compensation -- including those who are once again facing threats to their sovereignty, for example at Standing Rock.

Reckoning with this story and others like it should be central to how we interpret infrastructural landscapes, how we affirm and restore the rights marginalized communities, and how we reckon w/ this country& #39;s deeply colonial past.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter