<THREAD>

TITLE: The Serpent, Balaam’s Donkey, and the Cross.

Animals don’t speak much in the Hebrew Bible, so, when they do so, we should pay attention to them.

With that uncontroversial premise in mind, let’s take a look at Genesis 3 and Numbers 22–25.

TITLE: The Serpent, Balaam’s Donkey, and the Cross.

Animals don’t speak much in the Hebrew Bible, so, when they do so, we should pay attention to them.

With that uncontroversial premise in mind, let’s take a look at Genesis 3 and Numbers 22–25.

Although the serpent (in the garden of Eden) and Balaam’s donkey are quite different animals, their stories have a number of things in common.

Like Genesis 3, Balaam’s story contains a number of references to serpents,

Like Genesis 3, Balaam’s story contains a number of references to serpents,

some of which are explicit and others of which are homonyms of the word ‘serpent’ (נָחָשׁ).

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> Balaam arises against the backdrop of a plague of fiery serpents (נְחָשִׁים) (cp. 21.7–9).

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> Balaam arises against the backdrop of a plague of fiery serpents (נְחָשִׁים) (cp. 21.7–9).

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> At Balak’s behest, Balaam performs acts of ‘divination’ (נְחָשִׁים) (cp. 23.23, 24.1).

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> At Balak’s behest, Balaam performs acts of ‘divination’ (נְחָשִׁים) (cp. 23.23, 24.1).

Significantly, all of these serpentine allusions describe incidents in which Israel’s enemies are overcome by means of their own devices—where God fights fire with fire.

all of which is reminiscent of Gen. 3,

where YHWH says the seed of the woman will ‘bruise’ (שוף) the head of the serpent even as the serpent ‘bruises’ the heel of the woman’s seed,…

With these claims in mind, it’s not too hard to see how Balaam’s story can be viewed as part of a longer term theme woven into the Biblical narrative in which God overturns the curse of the serpent-induced sin.

At the outset of the creation story, man is blessed (Gen. 1.28).

Man’s line cannot, therefore, be entirely cursed,

on which see @DrPJWilliams: https://twitter.com/DrPJWilliams/status/1057424662588809217">https://twitter.com/DrPJWilli...

Man’s line cannot, therefore, be entirely cursed,

on which see @DrPJWilliams: https://twitter.com/DrPJWilliams/status/1057424662588809217">https://twitter.com/DrPJWilli...

So, in the aftermath of man’s sin, God doesn’t curse ‘man’ (אדם), but the ‘ground’ (אדמה).

And, amidst the pain (עצבון) of the curse, God provides hope in the form of a ‘seed’.

And, amidst the pain (עצבון) of the curse, God provides hope in the form of a ‘seed’.

That hope first finds an echo in man’s tenth generation in the birth of Noah,

whom God ‘blesses’ (9.1),

and of whom it’s said, ‘Out of the cursed ground (אדמה), he will bring relief from the painful toil (עצבון) of our hands’ (5.29).

whom God ‘blesses’ (9.1),

and of whom it’s said, ‘Out of the cursed ground (אדמה), he will bring relief from the painful toil (עצבון) of our hands’ (5.29).

And it finds a further echo another ten generations later in the birth of Abraham, of whom God says,

‘I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonours you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth (אדמה) will be blessed’ (12.3).

‘I will bless those who bless you, and him who dishonours you I will curse, and in you all the families of the earth (אדמה) will be blessed’ (12.3).

Thereafter, the covenant made with Noah and Abraham is perpetuated by means of their ‘seed’ (9.9, 12.7)...

...as the command ‘Be fruitful and multiply’ (1.28) is fulfilled by God’s promise, ‘I will make you fruitful’ (17.6, 20, 28.3, etc.).

...as the command ‘Be fruitful and multiply’ (1.28) is fulfilled by God’s promise, ‘I will make you fruitful’ (17.6, 20, 28.3, etc.).

With the advent of Balaam, however, an anti-Abraham arrives on the scene—a man with the (alleged) ability to curse what God has blessed, to undo God’s promise to Abraham.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> Like Abraham, Balaam sets out from Mesopotamia.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> Like Abraham, Balaam sets out from Mesopotamia.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> Like Abraham, Balaam receives a call (קרא).

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> Like Abraham, Balaam receives a call (קרא).

where he goes up to a high place (or, to be precise, three high places).

As we’ve noted, however, what God has blessed cannot be cursed. And so Balaam’s threat soon dissolves.

In his final discourse, the great diviner who is said to be able to bless and curse at will (cp. Num. 22.6’s אשר תברך מברך ואשר תאר יואר) is able only to confirm YHWH’s promise to Abraham,

namely, ‘Blessed are those who bless you, and cursed are those who curse you’ (מברכיך ברוך וארריך ארור) (Num. 24.9).

Hence, as Balaam departs at the end of Numbers 24, his illusion of autonomy in tatters, Balak’s intended object of attack—Israel—is not only left uncursed,

Hence, as Balaam departs at the end of Numbers 24, his illusion of autonomy in tatters, Balak’s intended object of attack—Israel—is not only left uncursed,

but is made a sanctuary and rock of offense (לְמִקְדָּשׁ וּלְאֶבֶן נֶגֶף) (Isa. 8.14).

Those who desire to bless Israel will find sanctuary in her, while those who seek her destruction will themselves be destroyed.

Those who desire to bless Israel will find sanctuary in her, while those who seek her destruction will themselves be destroyed.

With these things in mind, it’s instructive to note the various ways in which Balaam’s story contrasts the actions of the proverbially dumb donkey with those of the proverbially wise snake.

Balaam’s story thus begins with an inverted version of Genesis 3.

And, in Numbers 23–24, where Balaam assumes the role and ministry of his donkey (e.g., he thrice fails to do what he’s been told, angers his master, etc.), further inversions take place.

And, in Numbers 23–24, where Balaam assumes the role and ministry of his donkey (e.g., he thrice fails to do what he’s been told, angers his master, etc.), further inversions take place.

More specifically, YHWH employs Balaam’s divination (נחשׁ) to undo the curse of the serpent (נחשׁ). (The more creative reader may be tempted to read Balaam’s statement לא־נחשׁ ביעקב as ‘No serpent will harm Jacob!’)

GOD USES MEANS

But the reversal of creation’s curse and the restoration of an edenic state in the earth doesn’t materialise out of thin air.

Balaam frames it against the backdrop of a ‘seed’ which arises from Israel’s waters and a king who is raised up in Israel’s midst (24.7).

But the reversal of creation’s curse and the restoration of an edenic state in the earth doesn’t materialise out of thin air.

Balaam frames it against the backdrop of a ‘seed’ which arises from Israel’s waters and a king who is raised up in Israel’s midst (24.7).

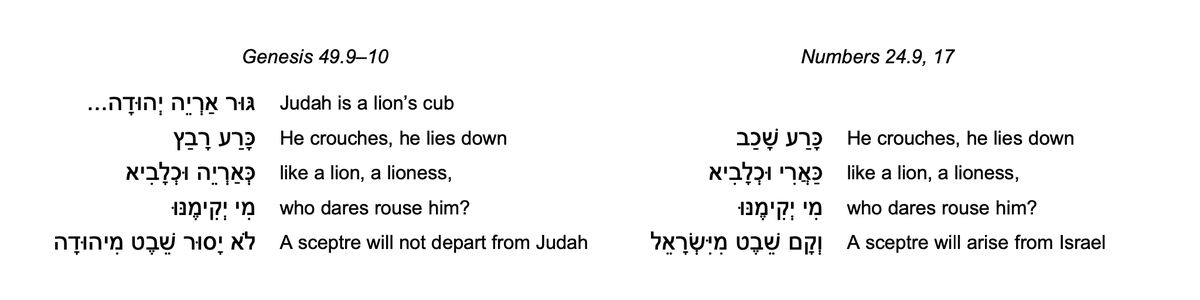

And Balaam later portrays that king as a lion-like warrior (24.9) and associates him with a sceptre (24.17),

which the Targums interpret Messianically.

which the Targums interpret Messianically.

As such, Balaam’s prophecy picks up the thread of Genesis 49.9–10’s prophecy,

where the divinely-blessed Jacob blesses his son Judah and speaks about a lion-like king who will arise from his line.

Indeed, the similarities between Balaam and Jacob’s words are pronounced:

where the divinely-blessed Jacob blesses his son Judah and speaks about a lion-like king who will arise from his line.

Indeed, the similarities between Balaam and Jacob’s words are pronounced:

Balaam’s edenic description is hence bound up with the ‘seed’ of the woman in Genesis 3 and, by extension, with the emergence of a king from the ranks of Judah.

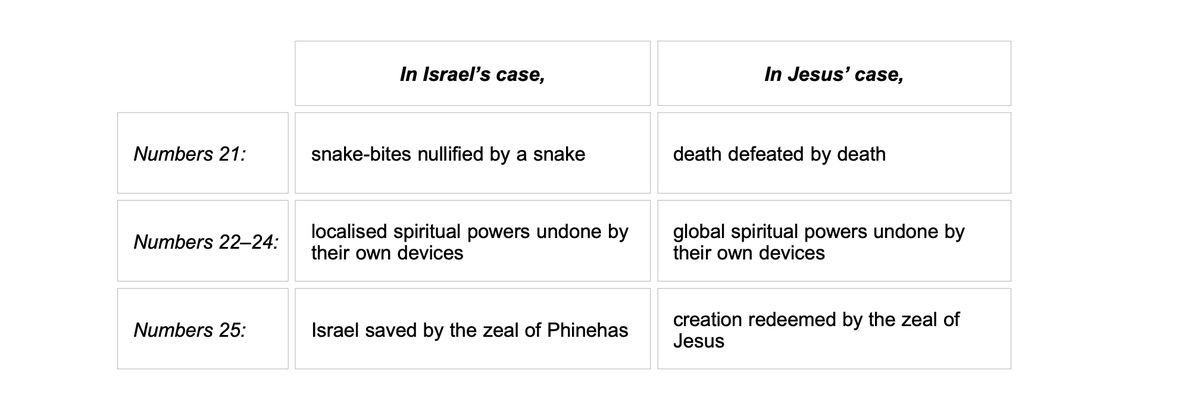

And, significantly, the NT’s description of how Jesus defeats Israel’s enemies is predicated on the theme of Numbers 21–25.

Just as, in Numbers 21–25, God brings about the defeat of Israel’s enemies by means of their own devices, so too does Jesus.

Just as, in Numbers 21–25, God brings about the defeat of Israel’s enemies by means of their own devices, so too does Jesus.

Poison is already present in the veins of many of those around him—that is to say, they are ‘already condemned’ (3.18). Yet, if they look towards the soon-to-be-lifted-up Son of Man, they will live (3.16).

whose crucifixion of Jesus seals their destiny (1 Cor. 2.8).

Also worthy of note is Balaam and Judas’s motive for their behaviour:

Also worthy of note is Balaam and Judas’s motive for their behaviour:

both men act in the way they do because of their love for ‘unrighteous gain’ (μισθός ἀδικίας)—a phrase employed only to describe Balaam and Judas in the NT (Acts 1.18, 2 Pet. 2.15).

Consumed by ‘zeal for YHWH’s house’, Jesus voluntarily puts himself in harm’s way, and ‘the reproaches of those who reproach YHWH fall upon him’ (Psa. 69.9, John 2.17).

In Jesus’ case, however, the guilty party is not pierced (דקר) by a spear. Instead, Jesus is pierced (דקר) (Zech. 12.10).

The lion of Judah he may be, yet he does not lift himself up like a lion (כארי) (Num. 23.24).

The lion of Judah he may be, yet he does not lift himself up like a lion (כארי) (Num. 23.24).

Rather, he walks into the lion’s den like a lamb (Psa. 22.13, 21), where his hands and feet are wounded ‘as if by lions’ (כארי) (Psa. 22.15–16).

The serpent may, therefore, be said to have bruised Jesus’ heel on the cross, yet, as Jesus tasted the curse of sin—namely the dust of death and sting of thorns—, he crushed the serpent’s head (Psa. 22, Matt. 27, Rom. 16.20).

As Samuel Gandy puts it,

By weakness and defeat,

he won a glorious crown;

trod all our foes beneath his feet,

by being trodden down.

He Satan’s power laid low;

made sin, he sin o’erthrew;

bowed to the grave, destroyed it so,

and death, by dying, slew.

By weakness and defeat,

he won a glorious crown;

trod all our foes beneath his feet,

by being trodden down.

He Satan’s power laid low;

made sin, he sin o’erthrew;

bowed to the grave, destroyed it so,

and death, by dying, slew.

A FINAL REFLECTION

That Balaam’s story is a strange one is quite true, yet it is by no means incoherent, nor is it unrelated to its context.

It picks up and runs with a number of threads of the Biblical narrative,

That Balaam’s story is a strange one is quite true, yet it is by no means incoherent, nor is it unrelated to its context.

It picks up and runs with a number of threads of the Biblical narrative,

which it weaves together in order to form a complex and coherent picture.

Equally important to note is the distinctiveness of the role played by Balaam’s donkey in our text.

Balaam’s dialogue with his donkey is sometimes associated with ancient Near Eastern ‘fables’.

Equally important to note is the distinctiveness of the role played by Balaam’s donkey in our text.

Balaam’s dialogue with his donkey is sometimes associated with ancient Near Eastern ‘fables’.

Yet, in such fables, animals play stereotypical roles (which is part of their utility), and they invariably dialogue with one another rather than with humans (Savran 1994).

By contrast, Balaam’s donkey acts in a highly un-donkey-like manner, and interacts directly with mankind,

By contrast, Balaam’s donkey acts in a highly un-donkey-like manner, and interacts directly with mankind,

which is fundamental to her role in Numbers 22–24.

Balaam’s story is, therefore, a story which is best analysed not by reference to comparative ANE material, but by reference to its particular role within Numbers 22–24 and the wider Biblical narrative.

</THREAD>

Balaam’s story is, therefore, a story which is best analysed not by reference to comparative ANE material, but by reference to its particular role within Numbers 22–24 and the wider Biblical narrative.

</THREAD>

P.S. With many thanks to @DrJimHamilton for a great paper on the subject, which is available here:

https://legacy.tyndalehouse.com/tynbul/Library/TynBull_2007_58_2_05_Hamilton_SeedOfWoman.pdf">https://legacy.tyndalehouse.com/tynbul/Li...

https://legacy.tyndalehouse.com/tynbul/Library/TynBull_2007_58_2_05_Hamilton_SeedOfWoman.pdf">https://legacy.tyndalehouse.com/tynbul/Li...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter

And, whereas the serpent tempts Eve to acquire an unlawful knowledge of ‘good and evil’ (טוב ורע), God won’t allow Balaam to do ‘good’ or ‘evil’ without his permission (24.13), and so, since God is ‘pleased’ (טוב) to bless Israel, Balaam can only see ‘good’ in Israel (24.5)." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> And, whereas the serpent tempts Eve to acquire an unlawful knowledge of ‘good and evil’ (טוב ורע), God won’t allow Balaam to do ‘good’ or ‘evil’ without his permission (24.13), and so, since God is ‘pleased’ (טוב) to bless Israel, Balaam can only see ‘good’ in Israel (24.5)." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

And, whereas the serpent tempts Eve to acquire an unlawful knowledge of ‘good and evil’ (טוב ורע), God won’t allow Balaam to do ‘good’ or ‘evil’ without his permission (24.13), and so, since God is ‘pleased’ (טוב) to bless Israel, Balaam can only see ‘good’ in Israel (24.5)." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔹" title="Kleine blaue Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine blaue Raute"> And, whereas the serpent tempts Eve to acquire an unlawful knowledge of ‘good and evil’ (טוב ורע), God won’t allow Balaam to do ‘good’ or ‘evil’ without his permission (24.13), and so, since God is ‘pleased’ (טוב) to bless Israel, Balaam can only see ‘good’ in Israel (24.5)." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>