[THREAD: BRAHMINS, NAWABS, SHAMPOO, AND KENNEDY]

1/71

The White Man oppresses the Black Man. That& #39;s the most enduring statement on the Western society and its legacy. But go back a few centuries and new stratifications emerge. I examine one here.

1/71

The White Man oppresses the Black Man. That& #39;s the most enduring statement on the Western society and its legacy. But go back a few centuries and new stratifications emerge. I examine one here.

2/71

India& #39;s biggest claim to notoriety is its Hindu caste system, a hierarchical totem pole with Brahmins on top and Shudras at the bottom. While the structure remains in place even today, it& #39;s far more elastic compared to how it was just two centuries ago.

India& #39;s biggest claim to notoriety is its Hindu caste system, a hierarchical totem pole with Brahmins on top and Shudras at the bottom. While the structure remains in place even today, it& #39;s far more elastic compared to how it was just two centuries ago.

3/71

But this wasn& #39;t the only totem pole those days. There was another, a political one, that placed rulers above the plebians. Amongst those were some so steeped in wealth that "let them eat cake" was a lived reality of their times. These were India& #39;s nawabs.

But this wasn& #39;t the only totem pole those days. There was another, a political one, that placed rulers above the plebians. Amongst those were some so steeped in wealth that "let them eat cake" was a lived reality of their times. These were India& #39;s nawabs.

4/71

Of course, on top of every Indian hierarchy was the East India Company. But the nawabs, or nabobs as the British called them, enjoyed quite the esteem and awe even in European imagination. Their opulence was a subject of contemporary legend.

Of course, on top of every Indian hierarchy was the East India Company. But the nawabs, or nabobs as the British called them, enjoyed quite the esteem and awe even in European imagination. Their opulence was a subject of contemporary legend.

5/71

By the mid-1700s, the glitz had so gripped the mainstream British imagination that nabob entered popular lexicon as a common noun for anyone with an obscene amount of wealth regardless of their political status. More specifically, the term came to define a smaller subset.

By the mid-1700s, the glitz had so gripped the mainstream British imagination that nabob entered popular lexicon as a common noun for anyone with an obscene amount of wealth regardless of their political status. More specifically, the term came to define a smaller subset.

6/71

Many Company officers those days would come to India on deputation for a few years, make a killing, and return to England several times wealthier than they& #39;d been when they first sailed. India was their windfall. Just as the Middle East is for many Indians today.

Many Company officers those days would come to India on deputation for a few years, make a killing, and return to England several times wealthier than they& #39;d been when they first sailed. India was their windfall. Just as the Middle East is for many Indians today.

7/71

These returning retirees would then use their fortune to build themselves lavish manors and castles, and even buy seats in the British Parliament. This would greatly enhance their status in a highly class-riddled 18th-century England. The perks were tempting.

These returning retirees would then use their fortune to build themselves lavish manors and castles, and even buy seats in the British Parliament. This would greatly enhance their status in a highly class-riddled 18th-century England. The perks were tempting.

8/71

This class of nouveau riche came to be commonly known as the nabobs of the English society. The word, of course, was a reference to the bejeweled nawabs of northern India, and in many ways, derisive. But to the nabobs themselves, this envy was a badge of honor.

This class of nouveau riche came to be commonly known as the nabobs of the English society. The word, of course, was a reference to the bejeweled nawabs of northern India, and in many ways, derisive. But to the nabobs themselves, this envy was a badge of honor.

9/71

Some of the prominent nabobs include names like Robert Clive, Warren Hastings, and Basil Cochrane. This last one is a lesser-known figure to most Indians because he didn& #39;t do much here besides amassing himself a mega fortune and leaving without much action.

Some of the prominent nabobs include names like Robert Clive, Warren Hastings, and Basil Cochrane. This last one is a lesser-known figure to most Indians because he didn& #39;t do much here besides amassing himself a mega fortune and leaving without much action.

10/71

Cochrane was the sixth son of a Scottish nobleman, the Earl of Dundonald. He joined the East India Company at the age of 16 and was immediately put on a boat to Madras as a revenue administrator. This was 1783. A stint with the Company was a tempting proposition those days.

Cochrane was the sixth son of a Scottish nobleman, the Earl of Dundonald. He joined the East India Company at the age of 16 and was immediately put on a boat to Madras as a revenue administrator. This was 1783. A stint with the Company was a tempting proposition those days.

11/71

Cochrane& #39;s windfall came about 10 years later in 1792 when he got hold of a provisions contract for the British Navy. Britain ruled the seas those days and imperialism demanded a robust and ever-expanding naval fleet. This meant unlimited opportunities.

Cochrane& #39;s windfall came about 10 years later in 1792 when he got hold of a provisions contract for the British Navy. Britain ruled the seas those days and imperialism demanded a robust and ever-expanding naval fleet. This meant unlimited opportunities.

12/71

In 1806, having raked up a fortune that ran into millions of pounds (each of his million would be 85 million today), Cochrane returned to England. London those days was the socialite capital of the world. Within London, was a neighborhood called Portman Square.

In 1806, having raked up a fortune that ran into millions of pounds (each of his million would be 85 million today), Cochrane returned to England. London those days was the socialite capital of the world. Within London, was a neighborhood called Portman Square.

13/71

Portman Square was to the 19th-century London what Bel Air is to today& #39;s Los Angeles. A millionaire row, if you will. Home to Counts and Lords and Barons and Salonnières, this is where the lines between timeless patricians and jump-start parvenus blurred beyond recognition.

Portman Square was to the 19th-century London what Bel Air is to today& #39;s Los Angeles. A millionaire row, if you will. Home to Counts and Lords and Barons and Salonnières, this is where the lines between timeless patricians and jump-start parvenus blurred beyond recognition.

14/71

It& #39;s this melting pot of nobility where Basil Cochrane decided to plant himself. It was a most predictable decision for a nabob like him. Soon, a large mansion was up at 12, Portman Square. It was lavish, well-appointed with every amenity known at the time, and big.

It& #39;s this melting pot of nobility where Basil Cochrane decided to plant himself. It was a most predictable decision for a nabob like him. Soon, a large mansion was up at 12, Portman Square. It was lavish, well-appointed with every amenity known at the time, and big.

15/71

So big, he used part of his property for business. This enterprise would multiply his fortune overnight thanks to its novelty in the British market. It was an exotic new way to shower. Something miraculously therapeutic. But before we get to it, let& #39;s take a quick detour.

So big, he used part of his property for business. This enterprise would multiply his fortune overnight thanks to its novelty in the British market. It was an exotic new way to shower. Something miraculously therapeutic. But before we get to it, let& #39;s take a quick detour.

16/71

Just when Cochrane was busy building his mansion, another visitor was on a boat to England. It was a Muslim man and his Catholic wife coming from Ireland to make a fresh start. His name was Sake Dean Mahomet, a European corruption of Shaikh Deen Mohammad.

Just when Cochrane was busy building his mansion, another visitor was on a boat to England. It was a Muslim man and his Catholic wife coming from Ireland to make a fresh start. His name was Sake Dean Mahomet, a European corruption of Shaikh Deen Mohammad.

17/71

Mahomet came from a long line of Muslim servants from the Indian state of Bihar traditionally employed by the Mughal court. With the decline of the empire, the family had turned to the East India Company, like most others of its kind. The pay was good, as was security.

Mahomet came from a long line of Muslim servants from the Indian state of Bihar traditionally employed by the Mughal court. With the decline of the empire, the family had turned to the East India Company, like most others of its kind. The pay was good, as was security.

18/71

Dean& #39;s father died when he was very young, which pushed the boy to seek employment with the Company in order to make ends meet. At work, he got to travel to far corners of the subcontinent accompanying his boss, an Irish officer named Godfrey Evan Baker.

Dean& #39;s father died when he was very young, which pushed the boy to seek employment with the Company in order to make ends meet. At work, he got to travel to far corners of the subcontinent accompanying his boss, an Irish officer named Godfrey Evan Baker.

19/71

Upon retirement, Baker returned to Ireland. With him, tagged along his aide and now, friend, Dean Mahomet. Deen continued to work for Baker managing his household for him. Ireland was a spectacularly racist society back then, just like any White nation.

Upon retirement, Baker returned to Ireland. With him, tagged along his aide and now, friend, Dean Mahomet. Deen continued to work for Baker managing his household for him. Ireland was a spectacularly racist society back then, just like any White nation.

20/71

However, Dean showed remarkable enthusiasm and success at assimilation. He would never return to India. As the first known Indian immigrant to Ireland, assimilation wasn& #39;t exactly easy, but he persisted. In time, he fell for and married a wealthy Irish girl named Jane.

However, Dean showed remarkable enthusiasm and success at assimilation. He would never return to India. As the first known Indian immigrant to Ireland, assimilation wasn& #39;t exactly easy, but he persisted. In time, he fell for and married a wealthy Irish girl named Jane.

21/71

Jane Daly and Dean Mahomet had to elope in order to escape her parents& #39; wrath. Love marriage wasn& #39;t much of a thing in feudal Europe those days. By the turn of the 19th century, the couple had decided to explore greener pastures across the Irish Sea.

Jane Daly and Dean Mahomet had to elope in order to escape her parents& #39; wrath. Love marriage wasn& #39;t much of a thing in feudal Europe those days. By the turn of the 19th century, the couple had decided to explore greener pastures across the Irish Sea.

22/71

This move was also necessitated by Baker& #39;s death upon which Dean Mahomet had to seek employment elsewhere. By then, though, he had made enough money to explore a better life in a more expensive Britain. So that& #39;s exactly what he did. London& #39;s best part was Portman Square.

This move was also necessitated by Baker& #39;s death upon which Dean Mahomet had to seek employment elsewhere. By then, though, he had made enough money to explore a better life in a more expensive Britain. So that& #39;s exactly what he did. London& #39;s best part was Portman Square.

23/71

Here, through a series of acquaintances and cold calls, Dean finally ended up in the employment of a very wealthy nabob by the name Basil Cochrane. How he met Cochrane is a long story in its own right, but not very pertinent to this thread, so we& #39;ll skip it.

Here, through a series of acquaintances and cold calls, Dean finally ended up in the employment of a very wealthy nabob by the name Basil Cochrane. How he met Cochrane is a long story in its own right, but not very pertinent to this thread, so we& #39;ll skip it.

24/71

In a way it was coming a full circle for Dean Mahomet. His forefathers had once served kings and nawabs in India. Now he was serving a nabob. At first he did what he was doing in Ireland. Managing Cochrane& #39;s household for him. But later, a new enterprise came up.

In a way it was coming a full circle for Dean Mahomet. His forefathers had once served kings and nawabs in India. Now he was serving a nabob. At first he did what he was doing in Ireland. Managing Cochrane& #39;s household for him. But later, a new enterprise came up.

25/71

From his own experiences in India, Cochrane had become privy to and intrigued by a very exotic Indian practice — the practice of vapor bath with herbs and massage. Indians called this message, champi. It was considered hygienic, but more importantly, therapeutic.

From his own experiences in India, Cochrane had become privy to and intrigued by a very exotic Indian practice — the practice of vapor bath with herbs and massage. Indians called this message, champi. It was considered hygienic, but more importantly, therapeutic.

26/71

Soon enough, with inputs and expertise from Dean Mahomet, Cochrane set up in his property, London& #39;s first therapeutic vapor bath facility. He marketed it as an exotic Oriental therapy that could fix arthritis, lethargy, and everything in between. The market was ripe.

Soon enough, with inputs and expertise from Dean Mahomet, Cochrane set up in his property, London& #39;s first therapeutic vapor bath facility. He marketed it as an exotic Oriental therapy that could fix arthritis, lethargy, and everything in between. The market was ripe.

27/71

Cochrane& #39;s vapor bath filled a niche nobody had until that point, even though every Company officer returning from India was aware of how Indians bathed. Dean helped set up the entire apparatus from scratch and also stock it with all necessary products.

Cochrane& #39;s vapor bath filled a niche nobody had until that point, even though every Company officer returning from India was aware of how Indians bathed. Dean helped set up the entire apparatus from scratch and also stock it with all necessary products.

28/71

Given its unique proposition, the business proved wildly successful. But despite Dean& #39;s indispensable contributions, Cochrane refused to share credits or limelight. Irked, Dean left after a while. All this while, he continued to make some money off his book.

Given its unique proposition, the business proved wildly successful. But despite Dean& #39;s indispensable contributions, Cochrane refused to share credits or limelight. Irked, Dean left after a while. All this while, he continued to make some money off his book.

29/71

Oh, we never talked about his book. Dean Mahomet loved traveling. And he loved writing. So he& #39;d make notes in his journal everytime he visited someplace new. And he had traveled extensively before emigrating from India. By the time he was in Ireland, he had written a lot.

Oh, we never talked about his book. Dean Mahomet loved traveling. And he loved writing. So he& #39;d make notes in his journal everytime he visited someplace new. And he had traveled extensively before emigrating from India. By the time he was in Ireland, he had written a lot.

30/71

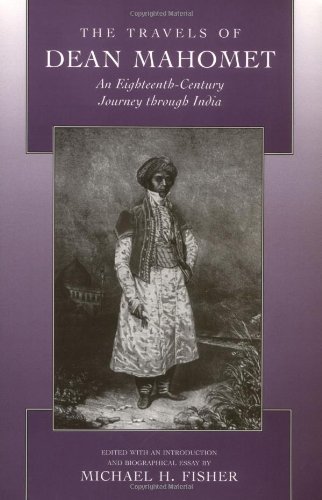

Since many Irish and British were traveling to India on job assignments with the EUC those days, Dean Mahomet decided to publish his notes as a guide to his native land for them. This he finally managed to do in 1794. It was titled "The Travels of Dean Mahomet."

Since many Irish and British were traveling to India on job assignments with the EUC those days, Dean Mahomet decided to publish his notes as a guide to his native land for them. This he finally managed to do in 1794. It was titled "The Travels of Dean Mahomet."

31/71

Travels was not only the first notable travel guide to India, it was the first English language book authored by an India. The book was a success and its royalties continued to keep Dean Mahomet afloat even after he quit Cochrane& #39;s bathhouse. But he needed a new business.

Travels was not only the first notable travel guide to India, it was the first English language book authored by an India. The book was a success and its royalties continued to keep Dean Mahomet afloat even after he quit Cochrane& #39;s bathhouse. But he needed a new business.

32/71

This new business couldn& #39;t be another bathhouse as it& #39;d be in direct competition to Cochrane& #39;s. So he picked something else. He started an Indian restaurant. And he picked Portman Square as the location because only the rich were expected to be open to exotic cuisines.

This new business couldn& #39;t be another bathhouse as it& #39;d be in direct competition to Cochrane& #39;s. So he picked something else. He started an Indian restaurant. And he picked Portman Square as the location because only the rich were expected to be open to exotic cuisines.

33/71

The place was called Hindoostane Coffee House and it was the Western world& #39;s first ever Indian restaurant. So by now, the humble Muslim from Bihar had given the West its 3 firsts: First Indian immigrant, first Indian English book, first Indian restaurant.

The place was called Hindoostane Coffee House and it was the Western world& #39;s first ever Indian restaurant. So by now, the humble Muslim from Bihar had given the West its 3 firsts: First Indian immigrant, first Indian English book, first Indian restaurant.

34/71

But the restaurant started failing after a while because the wealthy nobility with a palate for Indian food could easily afford dedicated kitchens for the cuisine with cooks imported from the subcontinent. And that& #39;s what they preferred over visiting a restaurant.

But the restaurant started failing after a while because the wealthy nobility with a palate for Indian food could easily afford dedicated kitchens for the cuisine with cooks imported from the subcontinent. And that& #39;s what they preferred over visiting a restaurant.

35/71

After a year or so, the restaurant had to shut down and Dean Mahomet verged on bankruptcy. A fresh start was needed. He started putting out job applications in local newspapers citing experiences with bathhouses and cooking. But nothing came by. Until one day.

After a year or so, the restaurant had to shut down and Dean Mahomet verged on bankruptcy. A fresh start was needed. He started putting out job applications in local newspapers citing experiences with bathhouses and cooking. But nothing came by. Until one day.

36/71

It was a job offer from a bathhouse in Brighton, the healthcare hub of England. The town was littered with bathhouses and sanatoriums of all sizes. Brighton is where Britain and even Europe came to recuperate. One such bathhouse wanted to do something exotic.

It was a job offer from a bathhouse in Brighton, the healthcare hub of England. The town was littered with bathhouses and sanatoriums of all sizes. Brighton is where Britain and even Europe came to recuperate. One such bathhouse wanted to do something exotic.

37/71

It wanted to add an Indian edge to its offerings and decided to hire an Indian native to complete the package. Dean Mahomet and his brown skin were the perfect pick. So the family — by now, they had almost half a dozen kids — moved to Brighton. The pay was good.

It wanted to add an Indian edge to its offerings and decided to hire an Indian native to complete the package. Dean Mahomet and his brown skin were the perfect pick. So the family — by now, they had almost half a dozen kids — moved to Brighton. The pay was good.

38/71

A fresh start was needed, and that& #39;s exactly what this was. But Dean was ambitious and soon went his own. He had saved up enough to buy and furnish a bathhouse of his own. So that& #39;s exactly what he did. Here, he made his champi the star attraction.

A fresh start was needed, and that& #39;s exactly what this was. But Dean was ambitious and soon went his own. He had saved up enough to buy and furnish a bathhouse of his own. So that& #39;s exactly what he did. Here, he made his champi the star attraction.

39/71

This champi became such a success that despite Brighton being stuffed with bathhouses of all kinds, Dean Mahomet became synonymous with the trade. They started calling him Dr. Brighton. Champi, with time, corrupted to shampoo. This was Dean& #39;s third contribution to the West.

This champi became such a success that despite Brighton being stuffed with bathhouses of all kinds, Dean Mahomet became synonymous with the trade. They started calling him Dr. Brighton. Champi, with time, corrupted to shampoo. This was Dean& #39;s third contribution to the West.

40/71

Dean Mahomet died a wealthy nabob himself, albeit much faded in popularity as compared to his heyday. His patrons at one time included names like King William IV and King George IV who even appointed him his "Royal Shampooing Surgeon."

Dean Mahomet died a wealthy nabob himself, albeit much faded in popularity as compared to his heyday. His patrons at one time included names like King William IV and King George IV who even appointed him his "Royal Shampooing Surgeon."

41/71

Basil Cochrane, the original nabob, had died childless in Paris, almost 30 years before Dean Mahomet. Cochrane was neither the first nabob, nor the last. The idea persisted well into the 20th century and well beyond the British shores.

Basil Cochrane, the original nabob, had died childless in Paris, almost 30 years before Dean Mahomet. Cochrane was neither the first nabob, nor the last. The idea persisted well into the 20th century and well beyond the British shores.

42/71

Not all nabobs had confined themselves to posh London neighborhood. Or even Britain. Some had made big enough fortunes to homestead in new but no longer uncharted lands. Many came to America. Many had become nabobs only after making a killing in America.

Not all nabobs had confined themselves to posh London neighborhood. Or even Britain. Some had made big enough fortunes to homestead in new but no longer uncharted lands. Many came to America. Many had become nabobs only after making a killing in America.

43/71

On a winter morning in 1848, a foreman found a shiny nugget while working at a lumber mill in San Francisco. Later, he and his employer tested the piece and learned it was gold. This kicked off a 7-year feeding frenzy known today as the California Gold Rush.

On a winter morning in 1848, a foreman found a shiny nugget while working at a lumber mill in San Francisco. Later, he and his employer tested the piece and learned it was gold. This kicked off a 7-year feeding frenzy known today as the California Gold Rush.

44/71

This frenzy saw its peak in 1849. The year saw prospecting immigrants from as far as Japan and China, colloquially referred to as the "forty-niners." If the name sounds familiar, blame it on the @49ers who even have gold in their team colors.

This frenzy saw its peak in 1849. The year saw prospecting immigrants from as far as Japan and China, colloquially referred to as the "forty-niners." If the name sounds familiar, blame it on the @49ers who even have gold in their team colors.

45/71

California Gold Rush triggered unprecedented gentrification of San Francisco which quickly burgeoned from a dusty settlement into a bustling metropolis that long outlived the rush itself. With gentrification, came new opportunities. One of these was railroad.

California Gold Rush triggered unprecedented gentrification of San Francisco which quickly burgeoned from a dusty settlement into a bustling metropolis that long outlived the rush itself. With gentrification, came new opportunities. One of these was railroad.

46/71

The Central Pacific Railroad was chartered in 1962 to build a railroad connecting Sacramento with San Francisco and beyond. This would eventually become part of the First Transcontinental Railroad. With the CPR, came what we now call the Big Four.

The Central Pacific Railroad was chartered in 1962 to build a railroad connecting Sacramento with San Francisco and beyond. This would eventually become part of the First Transcontinental Railroad. With the CPR, came what we now call the Big Four.

47/71

One of the four was the President of the railroad company, Leland Stanford. If this name sounds familiar, it& #39;s because he later founded a university on his family name. The second was the company& #39;s VP, Collis Huntington. You probably know him as founder of Huntington, WV.

One of the four was the President of the railroad company, Leland Stanford. If this name sounds familiar, it& #39;s because he later founded a university on his family name. The second was the company& #39;s VP, Collis Huntington. You probably know him as founder of Huntington, WV.

48/71

The remaining 2 names were partner Charles Crocker and treasurer Mark Hopkins. Together, these 4 came to be called the Big Four, an intimately-connected group of tycoons and philanthropists who were friends not only in business but also in life.

The remaining 2 names were partner Charles Crocker and treasurer Mark Hopkins. Together, these 4 came to be called the Big Four, an intimately-connected group of tycoons and philanthropists who were friends not only in business but also in life.

49/71

When the Big Four decided to settle down in San Francisco, given its entrepreneurial potential, they didn& #39;t know where to go. So they began scouting for a suitable spot.

After much scouting and a careful assessment, they finally picked California Hill.

When the Big Four decided to settle down in San Francisco, given its entrepreneurial potential, they didn& #39;t know where to go. So they began scouting for a suitable spot.

After much scouting and a careful assessment, they finally picked California Hill.

50/71

San Francisco is built on seven hills, which is what gives its streets their world-famous gradients. California Hill was one of them. This is where the Big Four decided to build homes. And before the turn of the century, they did. 4 magnificent mansions bedecked the hill.

San Francisco is built on seven hills, which is what gives its streets their world-famous gradients. California Hill was one of them. This is where the Big Four decided to build homes. And before the turn of the century, they did. 4 magnificent mansions bedecked the hill.

51/71

While Big Four remained an established name for this group, that also came to be individually called nabobs. Just like their British counterparts who struck gold in India. Soon, California Hill itself came to be called Nabob Hill, eventually corrupting to Nob Hill.

While Big Four remained an established name for this group, that also came to be individually called nabobs. Just like their British counterparts who struck gold in India. Soon, California Hill itself came to be called Nabob Hill, eventually corrupting to Nob Hill.

52/71

Nob Hill should sound familiar to those who have ever been to San Francisco. It still remains one of the most desirable pieces of real estate, not just in San Francisco but on the entire continent. The Big Four nabobs are still celebrated names in the neighborhood.

Nob Hill should sound familiar to those who have ever been to San Francisco. It still remains one of the most desirable pieces of real estate, not just in San Francisco but on the entire continent. The Big Four nabobs are still celebrated names in the neighborhood.

53/71

Just as the Big Four converged into San Francisco, another pocket of affluence was making its presence felt in slightly less charitable ways on the East Coast. This was old money and with a stronger pedigree; descendants of early Protestant Puritans.

Just as the Big Four converged into San Francisco, another pocket of affluence was making its presence felt in slightly less charitable ways on the East Coast. This was old money and with a stronger pedigree; descendants of early Protestant Puritans.

54/71

Sure some were of the nuveau riche kind like the nabobs of Britain, but most were aristocrats familiar with wealth for generations. This pedigree made them a cut above the nabobs. This made them superior. And they didn& #39;t shy away from making it known.

Sure some were of the nuveau riche kind like the nabobs of Britain, but most were aristocrats familiar with wealth for generations. This pedigree made them a cut above the nabobs. This made them superior. And they didn& #39;t shy away from making it known.

55/71

Although they were not royalty and America was not a feudal society, these New England families, almost all of whom were in Boston, did everything in their capacity to recreate the ambience. From dressing to architecture to demeanor to customs, they mimicked everything.

Although they were not royalty and America was not a feudal society, these New England families, almost all of whom were in Boston, did everything in their capacity to recreate the ambience. From dressing to architecture to demeanor to customs, they mimicked everything.

56/71

This lot of elites included families like the Bates, the Appletons, the Adams, the Bacons, the Cabots, and many more. Although not always, members of these families typically went to Harvard, dressed conservatively, and intermarried to preserve bloodline.

This lot of elites included families like the Bates, the Appletons, the Adams, the Bacons, the Cabots, and many more. Although not always, members of these families typically went to Harvard, dressed conservatively, and intermarried to preserve bloodline.

57/71

Unlike the nabobs, they didn& #39;t believe in ostentatious expression of affluence and stayed away from glitz and glamor. If this sounds like a rigid caste system, it probably was. If this reminds you of India, you& #39;re not alone. Say hi to Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Unlike the nabobs, they didn& #39;t believe in ostentatious expression of affluence and stayed away from glitz and glamor. If this sounds like a rigid caste system, it probably was. If this reminds you of India, you& #39;re not alone. Say hi to Oliver Wendell Holmes.

58/71

In 1861, Holmes released a novel on the Boston life titled Elsie Venner. In it, he wrote about Boston& #39;s aristocracy, the "Brahmin Caste of New England." He called them Boston Brahmins.

And just like their counterparts in India, they resented anyone outside their caste.

In 1861, Holmes released a novel on the Boston life titled Elsie Venner. In it, he wrote about Boston& #39;s aristocracy, the "Brahmin Caste of New England." He called them Boston Brahmins.

And just like their counterparts in India, they resented anyone outside their caste.

59/71

This resentment is older than Holmes& #39; novel though. At least by 20 years, if not more.

In the middle of the 19th century, Ireland was visited by a terrible famine. The Irish call it Gorta Mór, or the Great Famine. We call it the Irish Potato Famine.

This resentment is older than Holmes& #39; novel though. At least by 20 years, if not more.

In the middle of the 19th century, Ireland was visited by a terrible famine. The Irish call it Gorta Mór, or the Great Famine. We call it the Irish Potato Famine.

60/71

The famine killed upward of a million and drove many to leave the country. America, by then, had built a reputation as the homesteader& #39;s Promised Land. So, many of these starving Irish refugees wound up in boats headed across the Atlantic.

The famine killed upward of a million and drove many to leave the country. America, by then, had built a reputation as the homesteader& #39;s Promised Land. So, many of these starving Irish refugees wound up in boats headed across the Atlantic.

61/71

By the 1850s, these Irish immigrants had started flooding the streets of Boston, much to the Brahmins& #39; annoyance. They saw these tattered new visitors as an ugly blemish on their beautiful way of life, a disruption to the luxurious Boston tranquility.

By the 1850s, these Irish immigrants had started flooding the streets of Boston, much to the Brahmins& #39; annoyance. They saw these tattered new visitors as an ugly blemish on their beautiful way of life, a disruption to the luxurious Boston tranquility.

62/71

The bitterness grew with time and many clashes sparked between the two communities. The Irish, over time, managed to build themselves up too. Many Irish families put in a great deal of labor and amassed wealth that could rival at least some lesser Brahmins.

The bitterness grew with time and many clashes sparked between the two communities. The Irish, over time, managed to build themselves up too. Many Irish families put in a great deal of labor and amassed wealth that could rival at least some lesser Brahmins.

63/71

The Brahmin-Irish friction was driven as much by class as by religion. The Brahmins were Protestant and the Irish, Catholic.

In 1894, a Brahmin named Henry Cabot Lodge, Sr. organized the Immigration Restriction League to lobby for stricter immigration policies.

The Brahmin-Irish friction was driven as much by class as by religion. The Brahmins were Protestant and the Irish, Catholic.

In 1894, a Brahmin named Henry Cabot Lodge, Sr. organized the Immigration Restriction League to lobby for stricter immigration policies.

64/71

The League was composed of fresh Brahmin graduates from Harvard University with Lodge as its sponsor. Lodge, in behalf of the League, introduced a bill in the Congress to make a literacy test one of the prerequisites to asylum.

The League was composed of fresh Brahmin graduates from Harvard University with Lodge as its sponsor. Lodge, in behalf of the League, introduced a bill in the Congress to make a literacy test one of the prerequisites to asylum.

65/71

The best illustration of the Brahmin snobbery comes from this doggerel by John Collins Bossidy:

And this is good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where the Lowells talk only to Cabots

And the Cabots talk only to God.

The best illustration of the Brahmin snobbery comes from this doggerel by John Collins Bossidy:

And this is good old Boston,

The home of the bean and the cod,

Where the Lowells talk only to Cabots

And the Cabots talk only to God.

66/71

Another description comes from a piece on the subject by S Foster Damon in a 1935 Atlantic issue. In it, he described then as living on the waterside of Beacon Street or the sunny side of Commonwealth Street, dining at two, and having tea (not coffee) at six.

Another description comes from a piece on the subject by S Foster Damon in a 1935 Atlantic issue. In it, he described then as living on the waterside of Beacon Street or the sunny side of Commonwealth Street, dining at two, and having tea (not coffee) at six.

67/71

Brahmins, Damon observed, sent their kids to Harvard and their dead to Mt. Auburn.

But the single most prominent name from Boston name wasn& #39;t even a Brahmin.

Among the Irish refugees that streamed into the city after the potato famine, were Patrick and Bridget.

Brahmins, Damon observed, sent their kids to Harvard and their dead to Mt. Auburn.

But the single most prominent name from Boston name wasn& #39;t even a Brahmin.

Among the Irish refugees that streamed into the city after the potato famine, were Patrick and Bridget.

68/71

It was 1849. America was rushing to California and Ireland was rushing to America.

The couple didn& #39;t stay jobless for very long as Patrick soon got a job as a barrel maker in Eastie, or East Boston, still an immigrant hub of the city just as it was back then.

It was 1849. America was rushing to California and Ireland was rushing to America.

The couple didn& #39;t stay jobless for very long as Patrick soon got a job as a barrel maker in Eastie, or East Boston, still an immigrant hub of the city just as it was back then.

69/71

Patrick and Bridget worked their way up the prosperity ladder through some of the most underrated episodes of discrimination in the history of America. The Brahmins wouldn& #39;t touch them with a barge pole, but the couple hammered on.

Patrick and Bridget worked their way up the prosperity ladder through some of the most underrated episodes of discrimination in the history of America. The Brahmins wouldn& #39;t touch them with a barge pole, but the couple hammered on.

70/71

Over the next 4 generations, the couple gave America several senators, bankers, the first chairman of the SEC, and finally, the unthinkable.

A Catholic President.

In 1961, John F Kennedy, great-grandson of Patrick Kennedy swore in as America& #39;s 35th President.

Over the next 4 generations, the couple gave America several senators, bankers, the first chairman of the SEC, and finally, the unthinkable.

A Catholic President.

In 1961, John F Kennedy, great-grandson of Patrick Kennedy swore in as America& #39;s 35th President.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter