Last year at @CompPolicyLab, we created the country’s first race-blind charging platform, intended to reduce racial bias in prosecutor’s charging decisions. We’ve analyzed the data! Here’s what happened when we deployed it in a major district attorney’s office (thread)

Before I dive into the details, it’s worth noting why this single decision is so important. If an individual is charged with a crime, they might be held in jail for months; and if eventually convicted, they might spend years in prison or on parole.

As a result, the decision to charge a case can incur enormous burdens for individuals and communities. That’s why it’s critical for district attorneys to strive for charging decisions that are free of racial bias.

Our team ( @joenudell, @ItsMrLin, @JulianNyarko, @5harad, and myself) partnered with a district attorney in a major American city to adopt and use our race-blind charging platform. We studied their behavior up to March of 2020, before the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic.

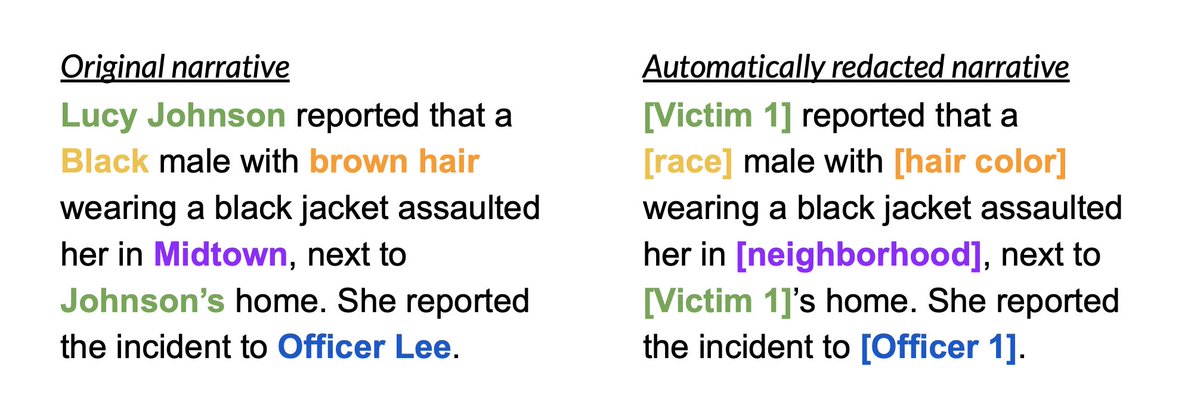

At the heart of our platform is a redaction algorithm that automatically masks race-related information from police incident narratives. Once a narrative has been redacted, prosecutors can understand the nuances of a case without learning the race of those involved.

How does this work? Of course, the algorithm redacts explicit mentions of race (like “Black”). But we also remove physical descriptors, people’s names, and any location information, given that these tidbits are often highly suggestive of one’s race.

What’s left is an entirely readable narrative that redacts race-related information while preserving all other information relevant to the charging decision. To make the point, here’s a toy example before and after redaction.

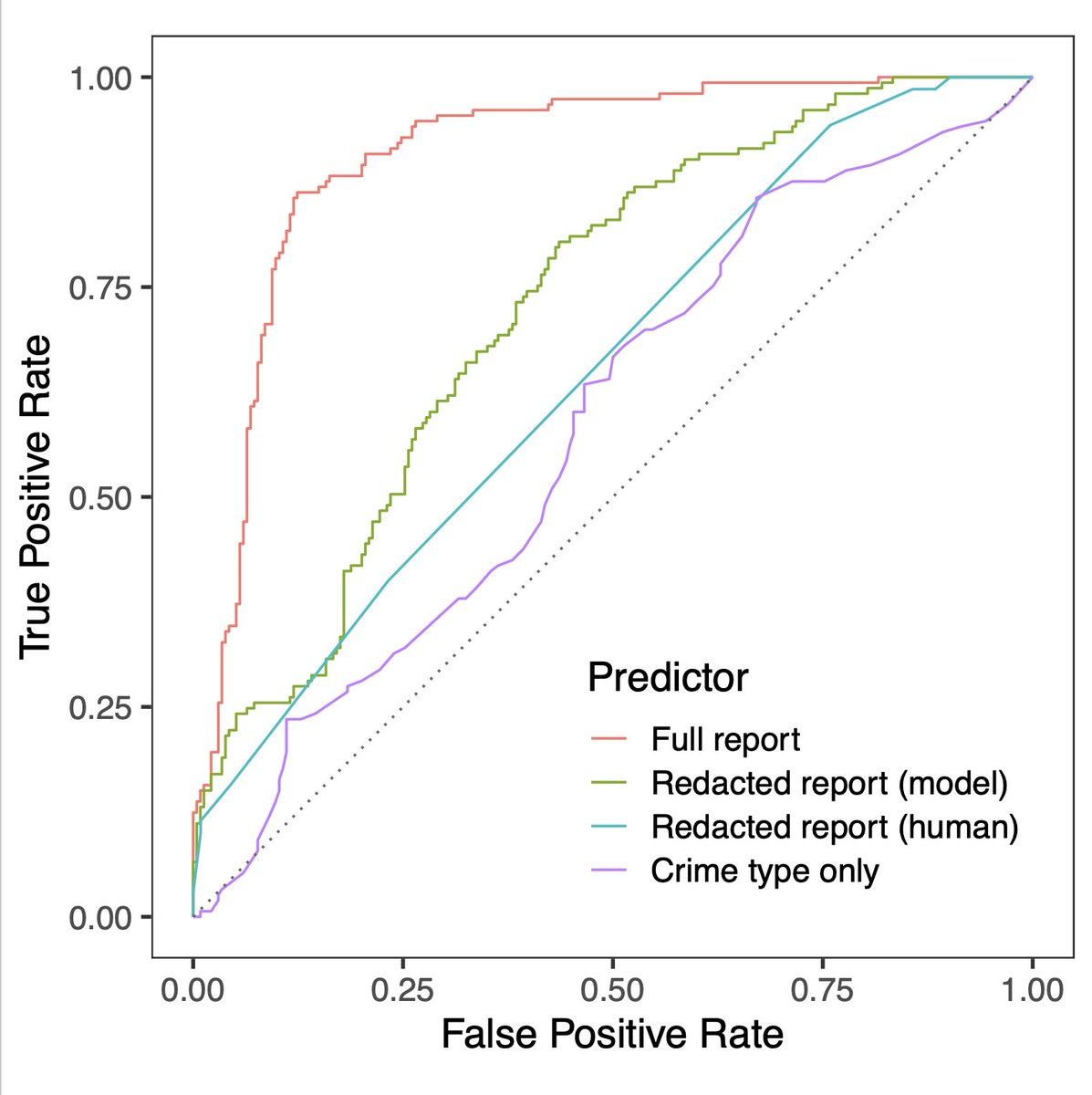

To check that it’s actually hard to infer someone’s race from our redacted reports, we had a researcher read the redacted reports and guess the race of each suspect. As a further test, we trained several machine learning models to do the same task.

We found that it’s difficult (but not impossible) to infer race from redacted narratives—partly because knowing the alleged crime type helps you infer a suspect’s race. But redaction makes it substantially harder to infer race when compared to the original.

Next, we wanted to know if our intervention actually changed charging decisions. We started by studying charging decisions before the start of our pilot.

Fortunately, we found no evidence of disparate treatment in historical charging decisions. So unsurprisingly—given this lack of disparate treatment historically—we also found that charging rates by race did not change with the use of race-blind charging.

On that note, though, a final **crucial** point: disparate treatment in charging decisions is wholly different from disparate impact in charging decisions. Both are forms of discrimination, but manifest very differently.

To put it succinctly:

Disparate treatment occurs when race influences decisions.

Disparate impact occurs when decisions influence race groups.

Disparate treatment occurs when race influences decisions.

Disparate impact occurs when decisions influence race groups.

Or here’s a theoretical (but realistic) example: even if charging decisions for marijuana possession are race-blind, if Black individuals are largely the only ones arrested for marijuana possession, the decision to charge these cases disproportionately impacts Black communities.

Our race-blind charging platform is intended to mitigate disparate treatment—one important form of discrimination. But the criminal justice system is rife with examples of harmful disparate impact on communities of color.

Race-blind charging, and race-blind decision-making in general, is only a first step. It’s also critical for agencies across the criminal justice pipeline to re-examine the effect of their policies, and reduce disproportionate impacts they might have on communities of color.

For more information on race-blind charging, see our paper here:

https://5harad.com/papers/blind-charging.pdf">https://5harad.com/papers/bl...

https://5harad.com/papers/blind-charging.pdf">https://5harad.com/papers/bl...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter