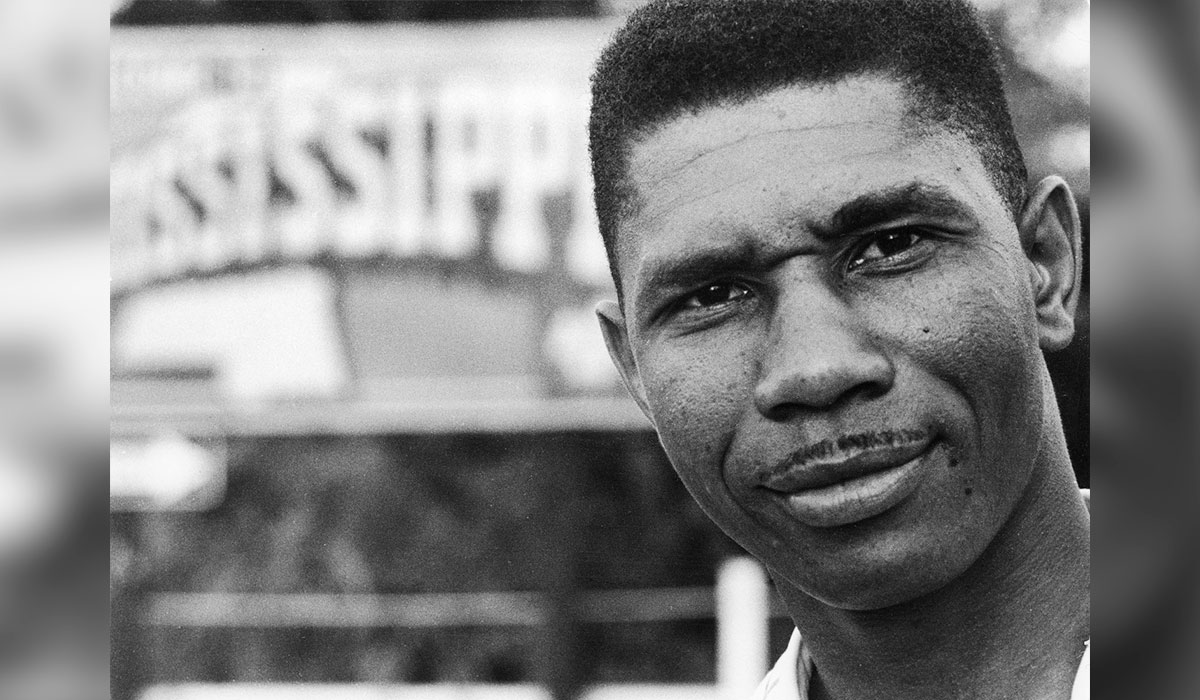

Rural Mississippi in 1925 was not a great time and place to have been born with brown skin.

But sometimes a man comes along at the wrong place at the wrong time, and still manages to change the course of history.

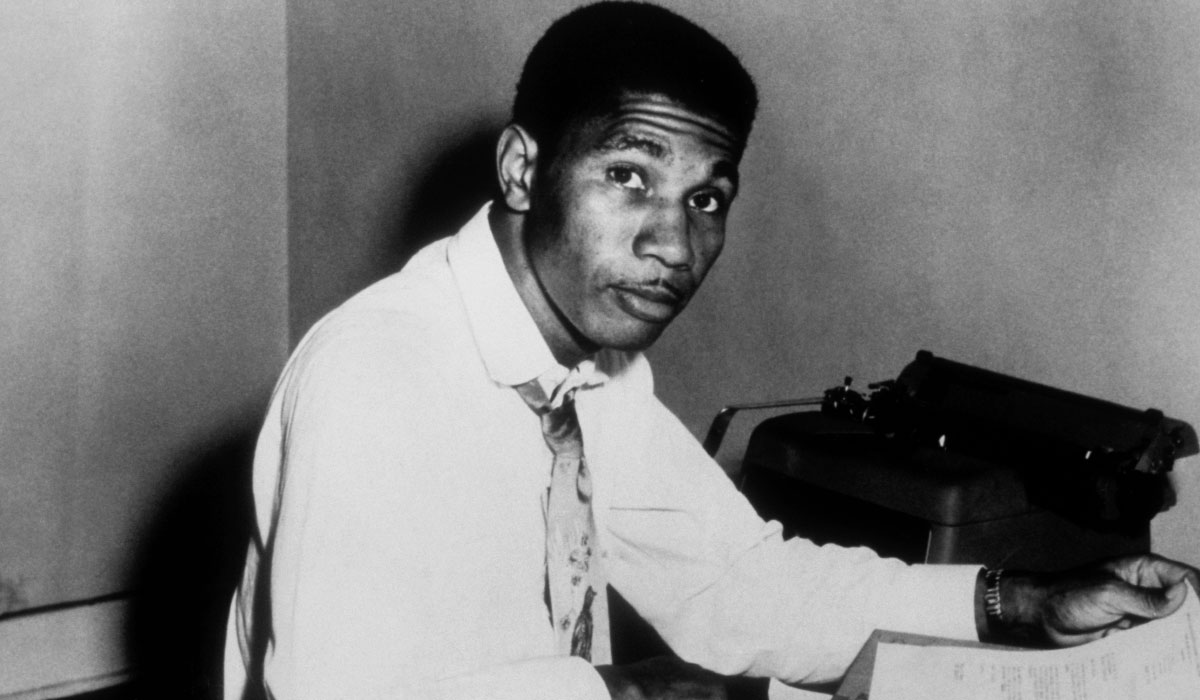

You& #39;re going to want to hear the story of Medgar Evers. Thread:

But sometimes a man comes along at the wrong place at the wrong time, and still manages to change the course of history.

You& #39;re going to want to hear the story of Medgar Evers. Thread:

White kids in Medgar Evers& #39; Mississippi town rode the bus to their school.

As a boy, Medgar would watch those busses pass him by as he walked along the side of the road 6 miles to school and 6 miles back each day. This wasn& #39;t the "back of the bus." It was off the bus altogether.

As a boy, Medgar would watch those busses pass him by as he walked along the side of the road 6 miles to school and 6 miles back each day. This wasn& #39;t the "back of the bus." It was off the bus altogether.

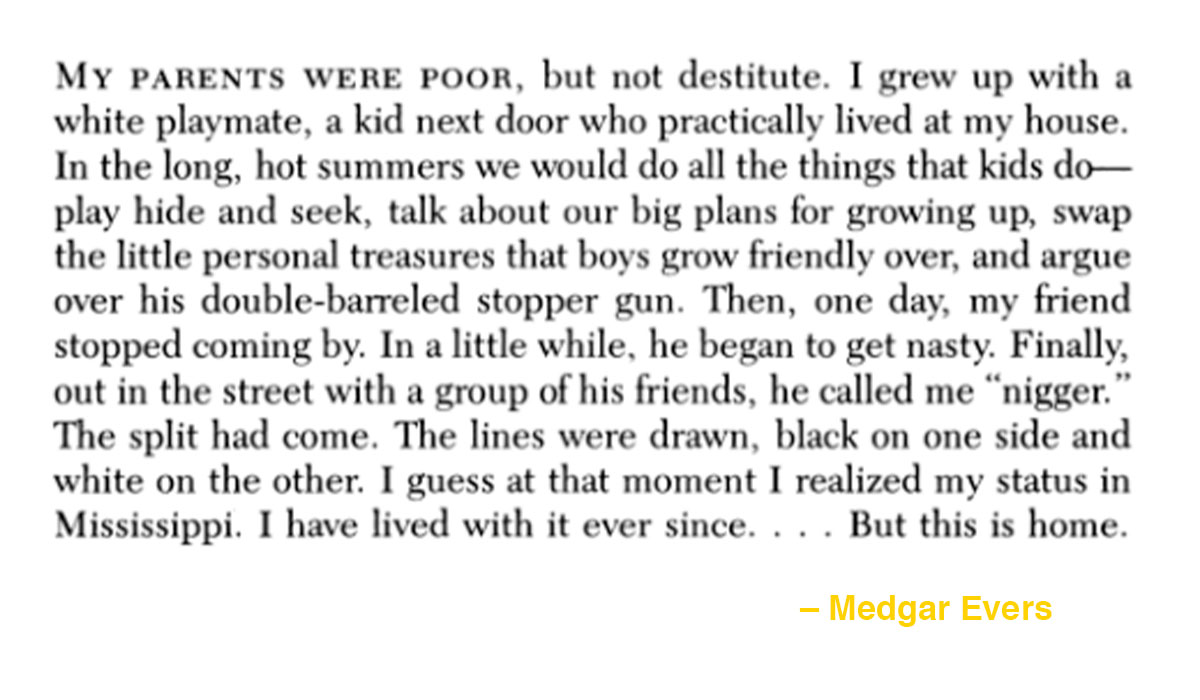

To paraphrase Nelson Mandela, no one is born racist. Racism is learned. And it is taught.

Read this soul-piercing memory from Medgar Evers about growing up as a young Black boy in Mississippi in the 1930s:

Read this soul-piercing memory from Medgar Evers about growing up as a young Black boy in Mississippi in the 1930s:

Many of us have formative moments in our lives that changed us forever. For Medgar Evers that moment came at age 14.

An adult family friend from down the street was lynched for "sassing a white woman" during a local fair. His death made Medgar determined to fight for change.

An adult family friend from down the street was lynched for "sassing a white woman" during a local fair. His death made Medgar determined to fight for change.

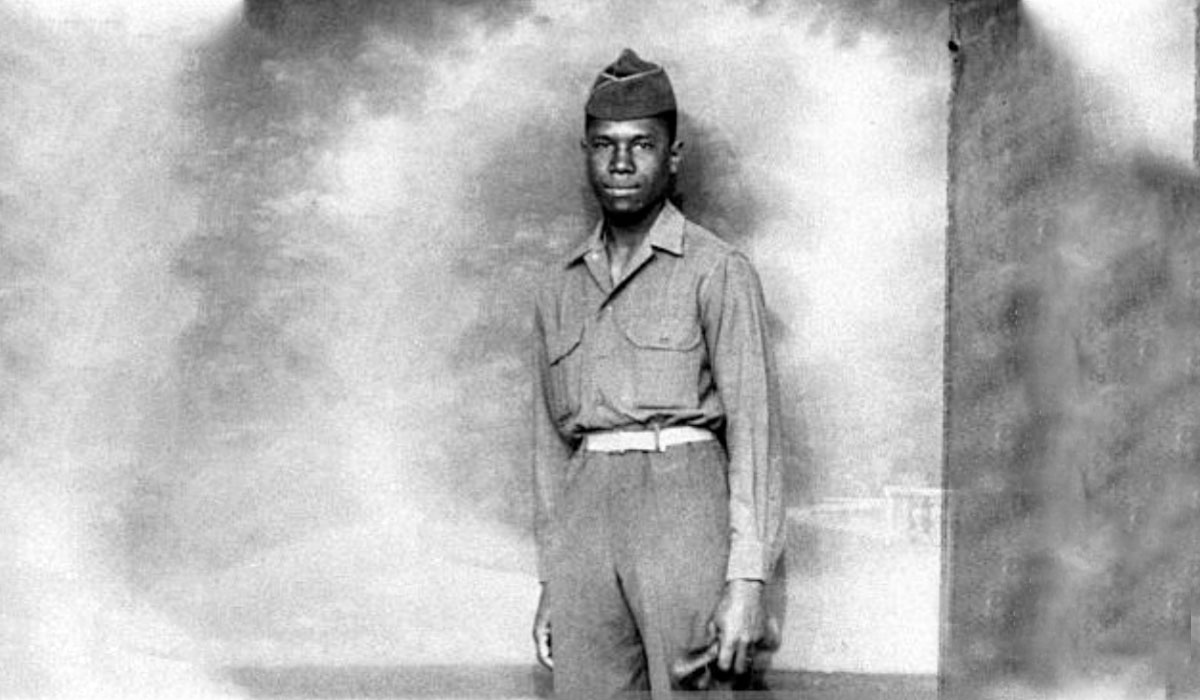

Growing up in Mississippi under Jim Crow you could have forgiven Medgar Evers if he had begun to quietly hate America.

Instead he put his life on the line for his country, lying about his age and following his older brother to enlist in the US Army fighting for freedom in WWII.

Instead he put his life on the line for his country, lying about his age and following his older brother to enlist in the US Army fighting for freedom in WWII.

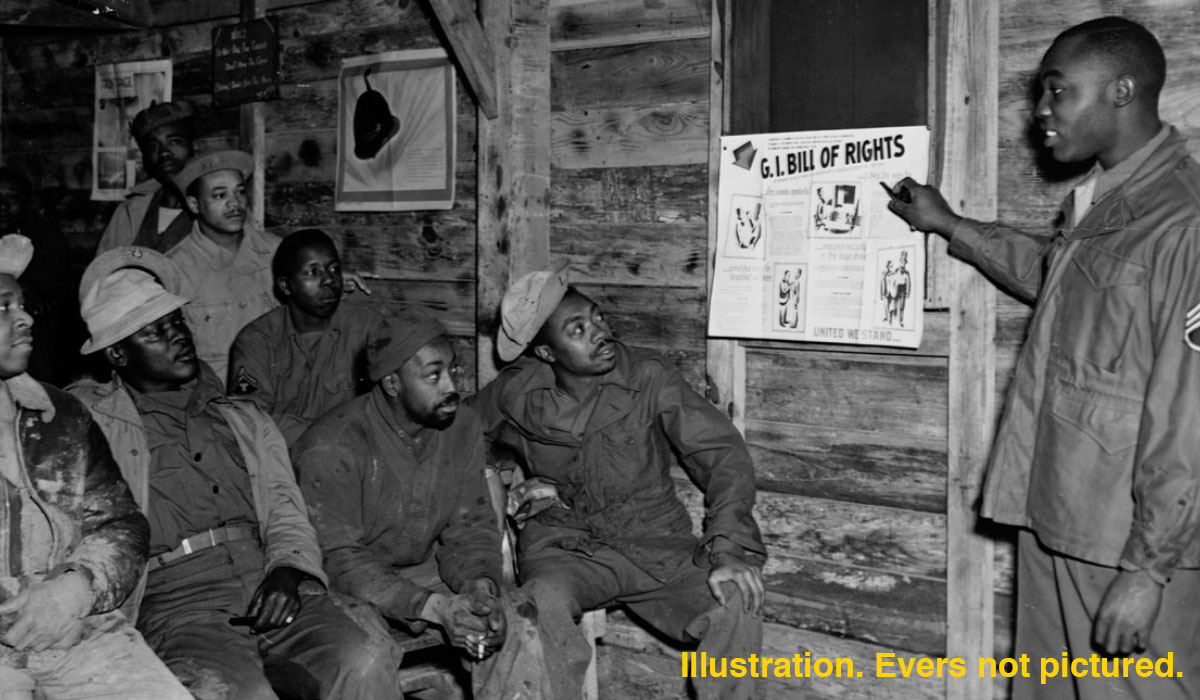

Starting in 1943 Medgar Evers served in an all-black unit of the 325th Port Company, led by white officers.

As part of the Normandy invasion of France Medgar fought for the freedom of people in far off lands, wearing the uniform of a country that did not treat him as a free man.

As part of the Normandy invasion of France Medgar fought for the freedom of people in far off lands, wearing the uniform of a country that did not treat him as a free man.

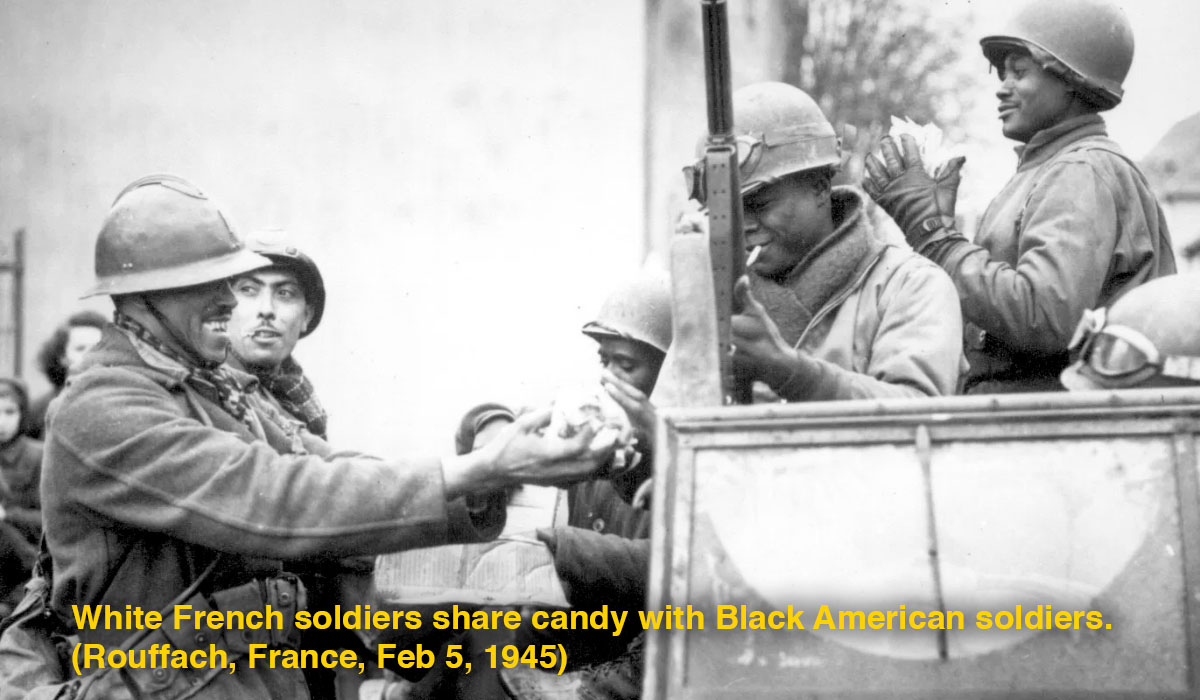

As they liberated France from Hitler many Black American soldiers were welcomed more warmly than they would be at home. It was a common experience.

After the end of World War II Medgar Evers returned to Mississippi wanting to bring home that same feeling of freedom to America.

After the end of World War II Medgar Evers returned to Mississippi wanting to bring home that same feeling of freedom to America.

After the end of WWII on the trip back home from Europe Medgar Evers convinced five of his fellow soldiers into registering to vote.

They would be 21 years old, the minimum legal age to vote at the time. They had fought bravely for their country abroad. But they were also Black.

They would be 21 years old, the minimum legal age to vote at the time. They had fought bravely for their country abroad. But they were also Black.

When Medgar Evers led his brother Charles and four other WWII veterans to register to vote in his hometown of Decatur Mississippi in 1946, they became the first Black men in the town& #39;s voter registry.

Six decorated Black veterans joined the 900 white voters of the town.

Six decorated Black veterans joined the 900 white voters of the town.

Whites showed up to intimidate Medgar Evers& #39; parents nightly, demanding he unregister to vote. His folks kept those visits a secret from him.

Imagine Black parents–themselves too afraid to register to vote–doing all they could to protect their son so he could be a full citizen.

Imagine Black parents–themselves too afraid to register to vote–doing all they could to protect their son so he could be a full citizen.

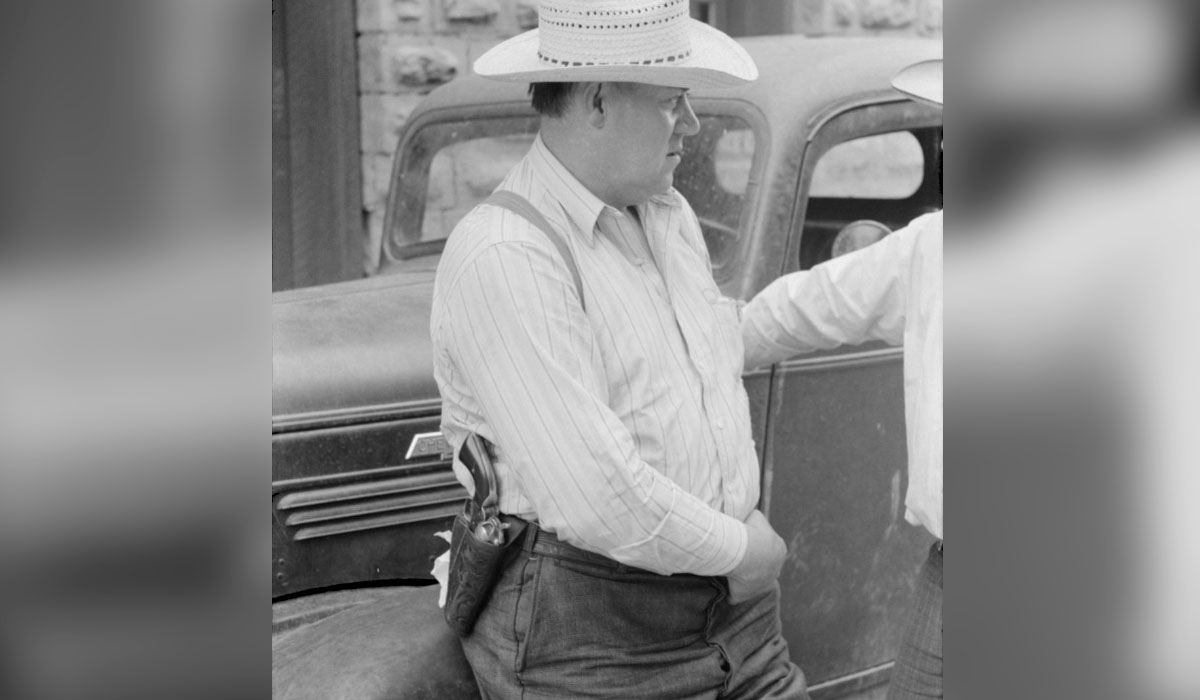

On election eve Mississippi& #39;s racist Sen Theodore Bilbo visited Medgar Evers& #39; hometown to whip up racist anger against the 6 Black WWII vets who had registered to vote.

"The best way to keep a n*gger from the polls on election day is to visit him the night before" he instructed.

"The best way to keep a n*gger from the polls on election day is to visit him the night before" he instructed.

Racist whites tried intimidate Medgar Evers at home the night before the election.

But the next day he showed up, leading his small group of Black vets to the county courthouse. The whole town seemed to know what would happen. They were the only Black men on the street that day.

But the next day he showed up, leading his small group of Black vets to the county courthouse. The whole town seemed to know what would happen. They were the only Black men on the street that day.

Armed whites met the Black WWII vets trying to register to vote.

"All we wanted was to be ordinary citizens. We fought during the war for America, Mississippi included. Now, after the Germans and the Japanese hadn& #39;t killed us, it looked as though the White Mississippians would."

"All we wanted was to be ordinary citizens. We fought during the war for America, Mississippi included. Now, after the Germans and the Japanese hadn& #39;t killed us, it looked as though the White Mississippians would."

Decatur Mississippi& #39;s white sheriff silently watched Medgar Evers and his group of Black WWII vets surrounded by armed white men on election day, his birthday. Police did not lift a finger to help them.

The veterans managed to escape. But they didn& #39;t get to vote that day.

The veterans managed to escape. But they didn& #39;t get to vote that day.

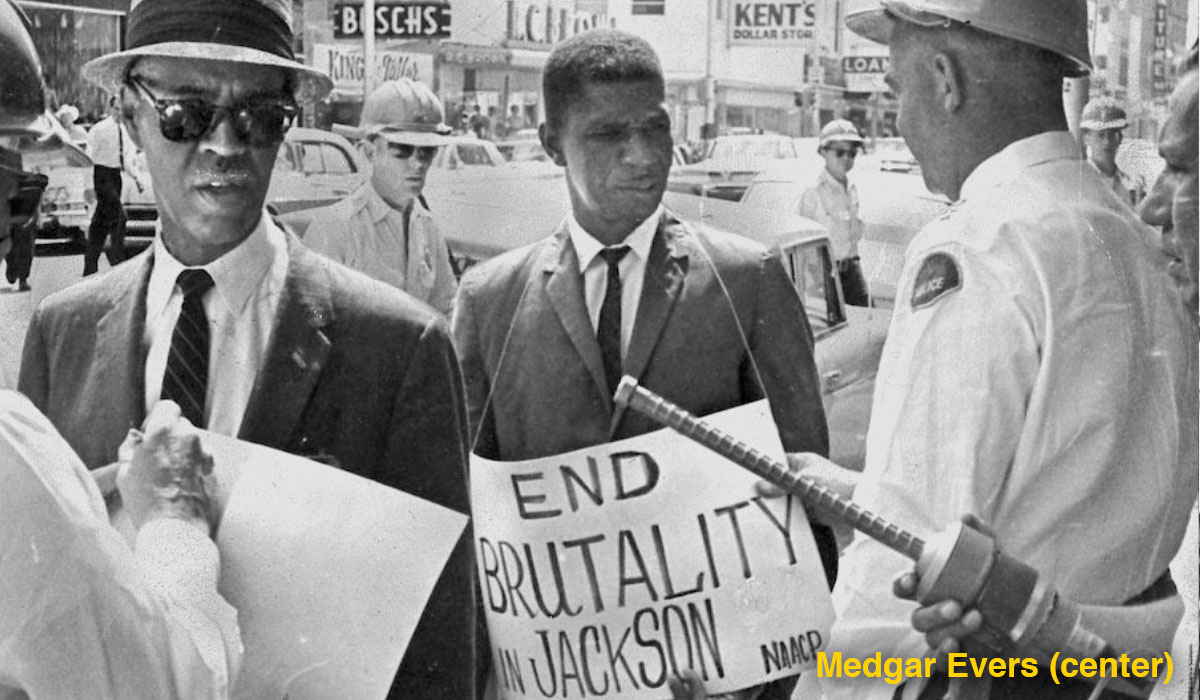

After whites threatened to lynch every single Black person in his hometown when he tried to vote, Medgar Evers resolved that he would never be turned away from a polling station ever again.

He marched. He gave speeches. He organized a local chapter of the NAACP.

He marched. He gave speeches. He organized a local chapter of the NAACP.

Theodore Bilbo, the Senator from Mississippi who whipped up racism against Blacks who wanted the right to vote won re-election.

But in an astonishing turn of events the US Senate refused to seat him, thanks to his remarks. Bilbo returned home and promptly died of oral cancer.

But in an astonishing turn of events the US Senate refused to seat him, thanks to his remarks. Bilbo returned home and promptly died of oral cancer.

Although Medgar Evers never became as famous as his fellow Civil Rights organizer Martin Luther King, he grew to be a force to be reckoned with in his home state of Mississippi.

But his effectiveness as a Black organizer eventually earned a target on his back.

But his effectiveness as a Black organizer eventually earned a target on his back.

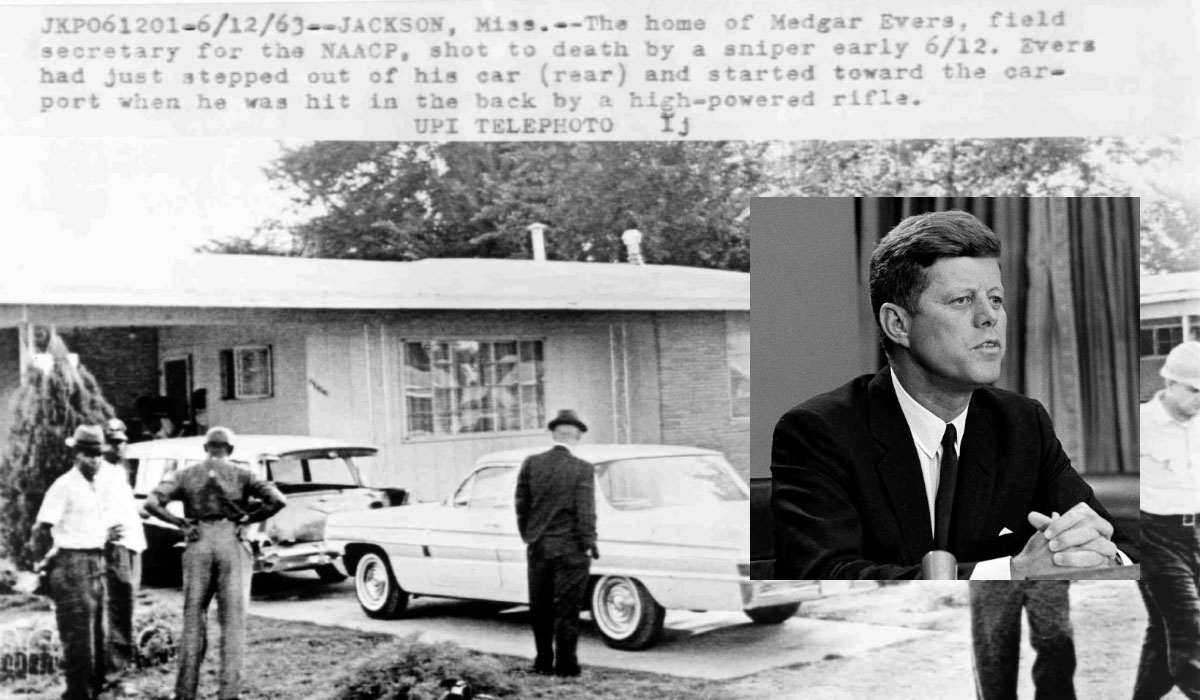

On the night of June 11, 1963 President Kennedy announced his support for the Civil Rights Movement in a major televised speech.

Hours later as Medgar Evers parked in his driveway, a stack of "Jim Crow Must Go" shirts he was carrying fell to the ground. A sniper had shot him.

Hours later as Medgar Evers parked in his driveway, a stack of "Jim Crow Must Go" shirts he was carrying fell to the ground. A sniper had shot him.

Medgar Evers& #39; young son Darrell recalls the night his father was murdered: "We were ready to greet him, because every time he came home it was special for us. He was traveling a lot at that time. All of a sudden, we heard a shot. We knew what it was."

Darrell hid in the bathtub.

Darrell hid in the bathtub.

Medgar Evers& #39; assassination just after Kennedy& #39;s Civil Rights speech shocked the nation. It crystallized the choice between right and wrong. Organizers rallied.

One year later, on what would have been Evers& #39; 39th birthday, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

One year later, on what would have been Evers& #39; 39th birthday, President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

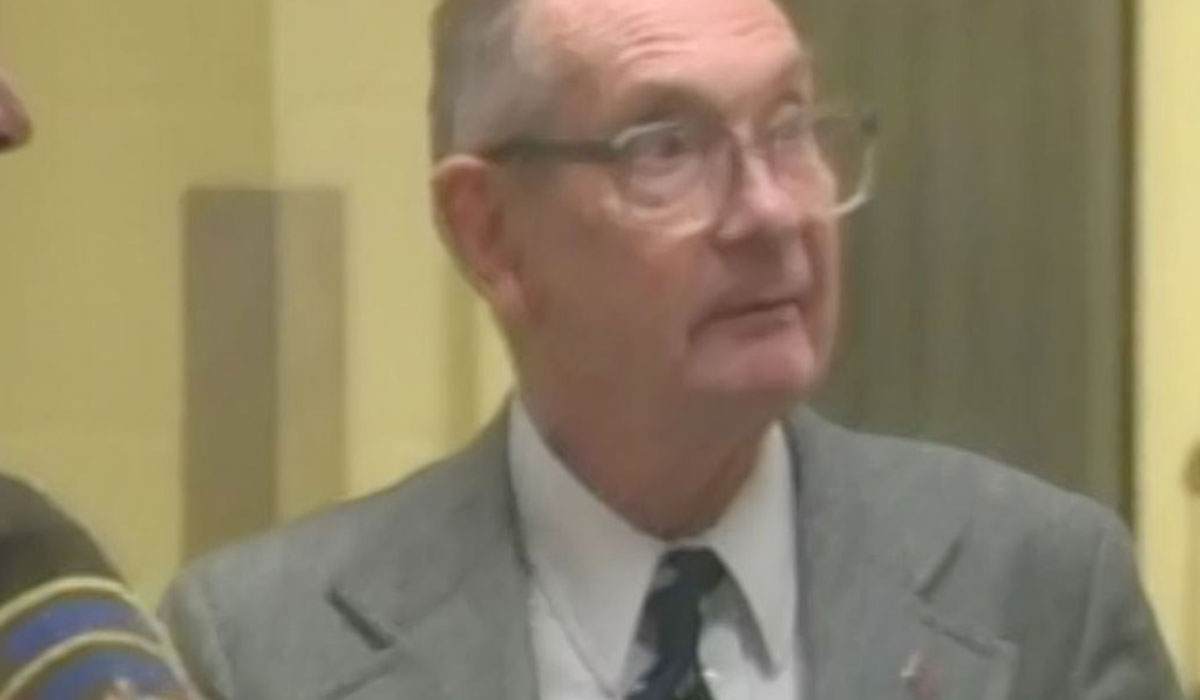

Medgar Evers& #39; murderer was local Klansman named Byron De La Beckwith.

Two all-white juries specially picked by Mississippi state government failed to find him guilty–despite his fingerprints on the murder weapon. He went on living his life a freer man than his victim ever did.

Two all-white juries specially picked by Mississippi state government failed to find him guilty–despite his fingerprints on the murder weapon. He went on living his life a freer man than his victim ever did.

Think about all the happy years of freedom that Medgar Evers& #39; killer lived after juries failed to convict him for the slaying of a civil rights hero. Years that Evers should have been alive. And voting.

If those stolen years don& #39;t churn your stomach, I don& #39;t know what could.

If those stolen years don& #39;t churn your stomach, I don& #39;t know what could.

After new evidence surfaced and attitudes towards race changed in Mississippi, Byron De La Beckwith was put on trial a third time in 1994.

Imagine how he felt finally getting convicted by a mostly Black jury at age 74. But his feelings did not matter. He went to prison and died.

Imagine how he felt finally getting convicted by a mostly Black jury at age 74. But his feelings did not matter. He went to prison and died.

Like many, Medgar Evers risked his life to vote. In the end it was a right he died for.

Now do you think he had great candidates to pick from in 1940s Mississippi? No. But he still put his life on the line to be able to choose.

Think about that when you hear people whining now.

Now do you think he had great candidates to pick from in 1940s Mississippi? No. But he still put his life on the line to be able to choose.

Think about that when you hear people whining now.

Medgar Evers& #39; brother Charles became Mississippi& #39;s first Black mayor since Reconstruction. He died on July 22, 2020.

Medgar& #39;s wife Myrlie delivered the invocation speech at Barack Obama& #39;s inauguration.

She is still alive. And you can be damn sure she is going to vote in 2020.

Medgar& #39;s wife Myrlie delivered the invocation speech at Barack Obama& #39;s inauguration.

She is still alive. And you can be damn sure she is going to vote in 2020.

If you learned something new about history from this thread, please consider sharing it.

If you want to make sure you don& #39;t miss out on another of my forgotten history threads, you can sign up to my substack. I only send history emails. No spam. https://arlen.substack.com/ ">https://arlen.substack.com/">...

If you want to make sure you don& #39;t miss out on another of my forgotten history threads, you can sign up to my substack. I only send history emails. No spam. https://arlen.substack.com/ ">https://arlen.substack.com/">...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter