I& #39;ve been waiting to read Vera Stein Ehrlich& #39;s (Vera St. Erlich& #39;s) book for ages; I finally found it in Stabi ten days ago & want to share some thoughts about her study on transformation of family in old Yugoslavia, based on research conducted in 300 villages across the country.

Vera Ehrlich (1897-1980) was born in Zagreb, where she studied psychology, but also moved to Vienna and Berlin. Being Jewish and antifascist, she had to flee Zagreb and spent the next few decades working for UNRA and teaching at Berkeley.

The book Jugoslavenska porodica u transformaciji (Yugoslav family in transition: a study of three hundred villages) is a fascinating attempt to understand the break-up of the old family structures across Yugoslavia before the WWII.

In the 1930s, Ehrlich was approached by three Bosnian Muslim students (Miralem Ljubović, Sulejman Azabagić and Muhamed Dusinović) who asked for help in the struggle of ‘’emancipation of Muslim women’’.

While she did not want to join their fight against face veil, she agreed to study Muslim family life. Slowly, the word spread around and many other Yugoslav students and teachers wanted to study their own contexts.

Ehrlich prepared the questionnaires about family life and sent them across the country. Teachers conducted research in individual villages and sent the answers back.

She knew she was racing against time. German invasion forced her to move to Dalmatia, and then onwards to South Italy. All that time, research material describing village life that no longer existed travelled with her in a trunk.

After the war, Vera Ehrlich lived in the USA, but insisted on the book to be published in Yugoslavia. It became an instant best-seller and was also translated into English and read at American universities as part of curriculum.

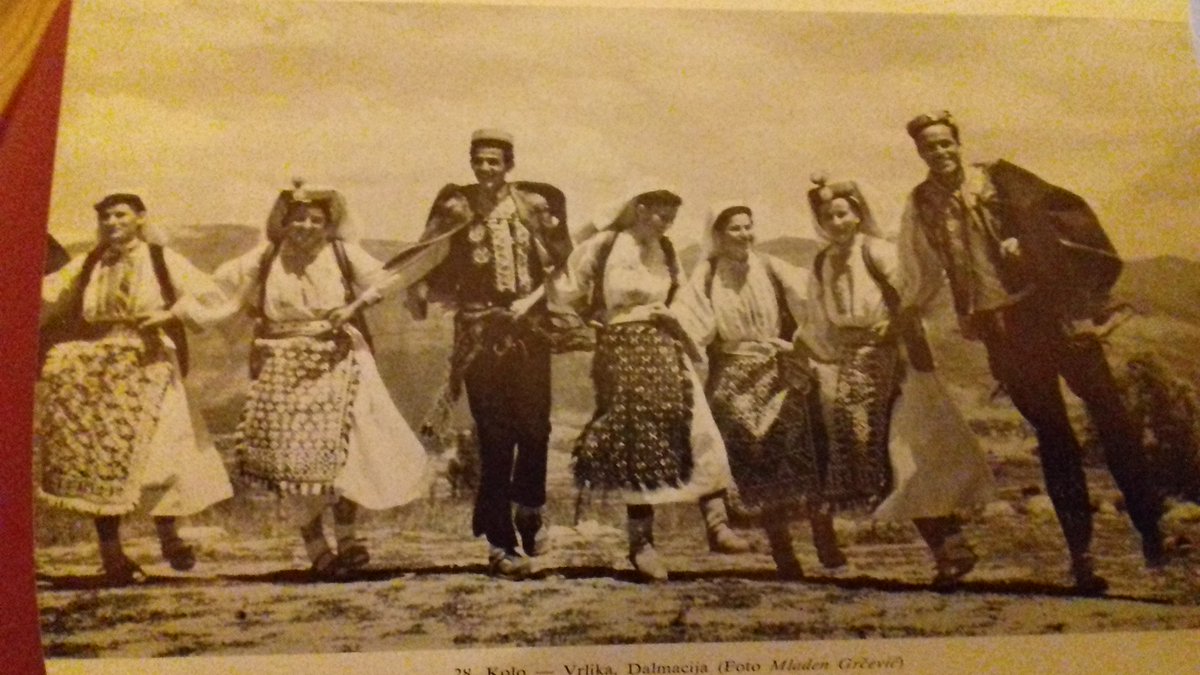

The book divides Yugoslav villages into several groups: Muslim Macedonia, Christian Macedonia, Muslim Bosnia, Christian Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia and Primorje. The division was done on a scale from ‘’old-fashioned/quaint’’ (starinski) to modern.

Major topics that were covered included descriptions of patriarchy – position of father, mother, mother-in-law, siblings, unmarried people, marriage, marital relations, children, adultery, alcoholism, literacy.

In every chapter, Ehrlich comparatively observes differences in family relations across Yugoslavia and how they were affected by modernity, especially the authority of father and husband, position of women, and individualism.

The results are surprising. Ehrlich suggests that traditional – patriarchal family had a certain stability to it where members were not equal, but their basic needs were met. Modern family offers stability as well, through increased egalitarianism.

It’s the family in transition that is the most violent, especially for women. Destruction of the authoritative role of the father does not bring prosperity for other members of the family. On the contrary, women are left to fend for themselves without means to do so.

Here Ehrlich emphasizes the case of Bosnia,the ultimate example of a society in transition. She often states the benevolent role of Islamic social framework for the position of women in traditional society, but indicates that it does not figure in some respects: e.g.alcoholism.

We cannot think about femininity without considering masculinity. The ‘’pauperization’’ of Bosnian Muslim men necessarily led to harder circumstances of life for Bosnian women.

The changes that occurred were a result of many external and internal factors, such as the transition from natural to monetary economy, dependence on international trade, and overall technological developments of the 20th century.

Ehrlich also gives some of her own explanations, many of which sound obsolete: Yugoslav Muslims are described as fatalist, their family life quaint and exotic. Albanian Muslims are especially essentialized with no apparent change going on.

The origin of regional differences Ehrlich locates at the time of the Ottoman rule. The more a society stayed under the Ottomans, the more old-fashioned it is. The Ottoman influence is ‘’Oriental’’ and shared by diffuse nations from Turkey to Mexico (Global South??)

Yet, despite its obsoleteness, the book raises some important questions such as the role of stability in human lives and how all the elements of the society are intricately connected to each other. It also speaks about the enduring links of belonging and love.

In many ways, and especially the way in which this book came into being, it reminded me of Tone Bringa’s & #39;& #39;Being Muslim the Bosnian Way& #39;& #39; that documented Bosnian Muslim lives that no longer exist today.

And postwar Bosnian village life is the subject of @henigdavid& #39;s exciting new book: https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/catalog/46pqw9wn9780252043291.html">https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/cat...

thread addendum - a heartbreaking detail (one of the many in this rich ethnography) which speaks about old values in a modern world:

Huso, a Bosnian Muslim man, wrote down all the things he purchased. His interviewer saw his notebook and noticed that it contained only +

Huso, a Bosnian Muslim man, wrote down all the things he purchased. His interviewer saw his notebook and noticed that it contained only +

bare necessities, sometimes a bit of coffee, meat very rarely. But it contained lots of chocolate. Why? Huso and his wife would buy it as gifts for other people. They themselves never tasted chocolate in their lives.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter