2/

Imagine that you& #39;re an electronics hobbyist.

You love tinkering with gadgets -- taking them apart, figuring out how they work, thinking of ways to improve them, etc.

You& #39;ve converted your garage into a lab of sorts, where you spend endless hours playing with your toys.

Imagine that you& #39;re an electronics hobbyist.

You love tinkering with gadgets -- taking them apart, figuring out how they work, thinking of ways to improve them, etc.

You& #39;ve converted your garage into a lab of sorts, where you spend endless hours playing with your toys.

3/

From a young age, you& #39;ve had a fascination for batteries and battery technology.

You& #39;re amazed by the progress we& #39;ve made.

Today, we have batteries that can power a full-sized car for hundreds of miles on a single charge.

But you know there& #39;s still a long way to go!

From a young age, you& #39;ve had a fascination for batteries and battery technology.

You& #39;re amazed by the progress we& #39;ve made.

Today, we have batteries that can power a full-sized car for hundreds of miles on a single charge.

But you know there& #39;s still a long way to go!

4/

One night, working late in your garage, a sudden brainwave hits you.

Why not use positively charged electrons (positrons) to store energy?

Such a "positronic battery" could have 10x the energy density, and one-tenth the charging time, of today& #39;s most advanced batteries!

One night, working late in your garage, a sudden brainwave hits you.

Why not use positively charged electrons (positrons) to store energy?

Such a "positronic battery" could have 10x the energy density, and one-tenth the charging time, of today& #39;s most advanced batteries!

5/

So you spend the next few weeks building a prototype and testing it.

And it works!

You find that your positronic battery can indeed power a car for 3000 miles on a single charge. And what& #39;s more, charging the battery takes only 10 minutes.

So you spend the next few weeks building a prototype and testing it.

And it works!

You find that your positronic battery can indeed power a car for 3000 miles on a single charge. And what& #39;s more, charging the battery takes only 10 minutes.

6/

The next steps are clear.

You get a patent.

Then you start a battery company: Positronics, Inc.

You meet with potential investors. Once you demonstrate to them that your battery is capable of driving a car *uphill*, you have no trouble raising money.

The next steps are clear.

You get a patent.

Then you start a battery company: Positronics, Inc.

You meet with potential investors. Once you demonstrate to them that your battery is capable of driving a car *uphill*, you have no trouble raising money.

7/

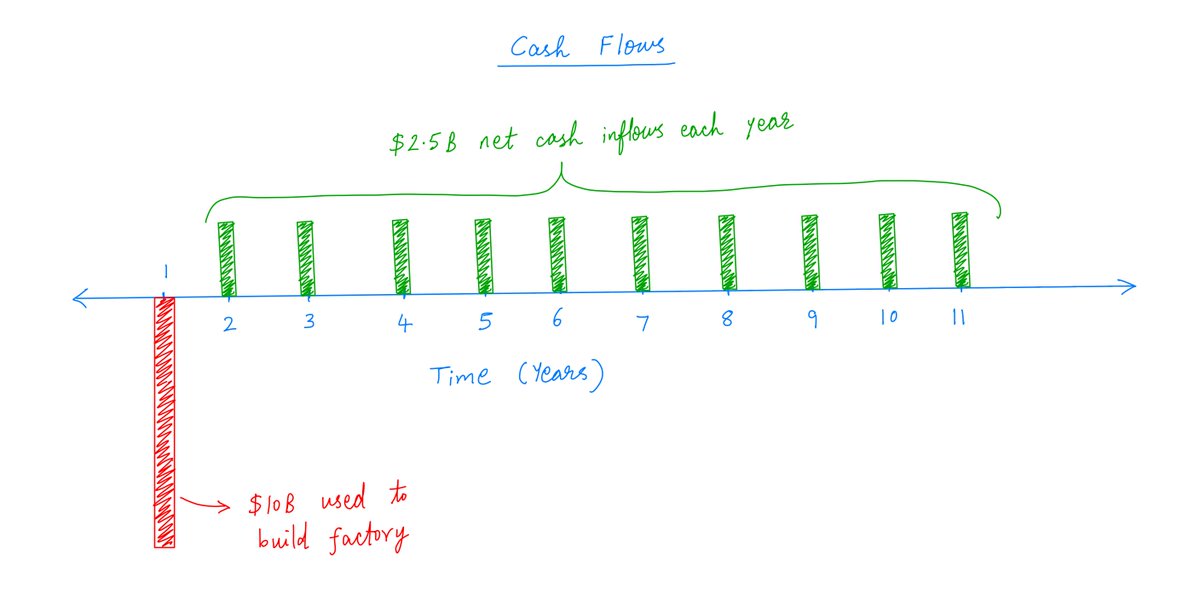

You raise $10B.

You use this money to build a factory. This takes about a year.

At the end of the year, you have a factory that& #39;s capable of manufacturing 3 million positronic batteries annually.

Finally, you& #39;re open for business -- ready to book your first battery order.

You raise $10B.

You use this money to build a factory. This takes about a year.

At the end of the year, you have a factory that& #39;s capable of manufacturing 3 million positronic batteries annually.

Finally, you& #39;re open for business -- ready to book your first battery order.

8/

So, between the time you started building the factory and the time you actually opened for business, one year has passed.

During this year, you had no revenue. But you spent $10B on the factory.

Does that mean your company lost $10B in its very first year?

So, between the time you started building the factory and the time you actually opened for business, one year has passed.

During this year, you had no revenue. But you spent $10B on the factory.

Does that mean your company lost $10B in its very first year?

9/

No.

The $10B spent on the factory was an *investment*, not an *expense*.

Sure, you spent $10B. But now, you have a factory that& #39;s worth $10B.

You didn& #39;t lose $10B. You just converted $10B of one asset (cash) into $10B of another asset (the factory).

No.

The $10B spent on the factory was an *investment*, not an *expense*.

Sure, you spent $10B. But now, you have a factory that& #39;s worth $10B.

You didn& #39;t lose $10B. You just converted $10B of one asset (cash) into $10B of another asset (the factory).

10/

So the first year was actually a *wash*.

*Not* a $10B loss.

Whew! That& #39;s a relief.

OK. What happens in subsequent years?

So the first year was actually a *wash*.

*Not* a $10B loss.

Whew! That& #39;s a relief.

OK. What happens in subsequent years?

11/

Let& #39;s say the factory has a useful life of 10 years.

That is, the factory will be able to manufacture 3 million batteries every year -- for the next 10 years.

After 10 years, everything in the factory will have worn out, and the whole factory will need to be rebuilt.

Let& #39;s say the factory has a useful life of 10 years.

That is, the factory will be able to manufacture 3 million batteries every year -- for the next 10 years.

After 10 years, everything in the factory will have worn out, and the whole factory will need to be rebuilt.

12/

From the moment we open for business, let& #39;s say demand is off the charts.

So we easily sell all the 3M batteries made by the factory each year.

We charge customers $2000 per battery.

So, our annual cash inflows are: (3M batteries) * ($2000 per battery) = $6B.

From the moment we open for business, let& #39;s say demand is off the charts.

So we easily sell all the 3M batteries made by the factory each year.

We charge customers $2000 per battery.

So, our annual cash inflows are: (3M batteries) * ($2000 per battery) = $6B.

13/

Let& #39;s say each battery costs us $1000 to make and sell.

This includes the cost of raw materials, employee salaries, electricity, insurance, etc. -- all paid in cash.

Thus, we have annual cash outflows of: (3M batteries) * ($1000 per battery) = $3B.

Let& #39;s say each battery costs us $1000 to make and sell.

This includes the cost of raw materials, employee salaries, electricity, insurance, etc. -- all paid in cash.

Thus, we have annual cash outflows of: (3M batteries) * ($1000 per battery) = $3B.

14/

So, we have cash inflows of $6B and cash outflows of $3B each year.

Does that mean our annual profits are $6B - $3B = $3B?

Unfortunately, the answer is no.

That& #39;s because these cash inflows and outflows haven& #39;t factored in the $10B sunk into the factory at the beginning.

So, we have cash inflows of $6B and cash outflows of $3B each year.

Does that mean our annual profits are $6B - $3B = $3B?

Unfortunately, the answer is no.

That& #39;s because these cash inflows and outflows haven& #39;t factored in the $10B sunk into the factory at the beginning.

15/

That $10B was a cash *outflow* in the very first year. Cash went out and the factory came in.

*After* the first year, the $10B had *no* impact on cash flows.

But we didn& #39;t count the $10B as a loss in the first year. So we should somehow account for it in subsequent years.

That $10B was a cash *outflow* in the very first year. Cash went out and the factory came in.

*After* the first year, the $10B had *no* impact on cash flows.

But we didn& #39;t count the $10B as a loss in the first year. So we should somehow account for it in subsequent years.

16/

This is where depreciation comes in.

The key idea is this:

Our factory is initially worth $10B. But after 10 years, it& #39;s worth nothing (as its useful life is only 10 years).

So, we deduct $10B/(10 years) = $1B per year from the value of the factory.

This is where depreciation comes in.

The key idea is this:

Our factory is initially worth $10B. But after 10 years, it& #39;s worth nothing (as its useful life is only 10 years).

So, we deduct $10B/(10 years) = $1B per year from the value of the factory.

17/

At the end of the Year 1, we open for business with a brand new factory worth $10B.

One year later, at the end of Year 2, our factory is worth only $9B.

At the end of Year 3, only $8B.

Finally, at the end of Year 11, the factory is worth $0.

That& #39;s depreciation.

At the end of the Year 1, we open for business with a brand new factory worth $10B.

One year later, at the end of Year 2, our factory is worth only $9B.

At the end of Year 3, only $8B.

Finally, at the end of Year 11, the factory is worth $0.

That& #39;s depreciation.

18/

This $1B per year reduction in factory value has to be treated as a cost for our business.

But notice that there isn& #39;t a $1B *cash* outflow each year.

Depreciation is a "non-cash expense".

This $1B per year reduction in factory value has to be treated as a cost for our business.

But notice that there isn& #39;t a $1B *cash* outflow each year.

Depreciation is a "non-cash expense".

19/

One way to think about depreciation is:

Instead of treating the $10B cash outflow in the very first year as an expense, we& #39;re treating it as 10 separate expenses of $1B each -- over the next 10 years (the useful life of the factory).

One way to think about depreciation is:

Instead of treating the $10B cash outflow in the very first year as an expense, we& #39;re treating it as 10 separate expenses of $1B each -- over the next 10 years (the useful life of the factory).

20/

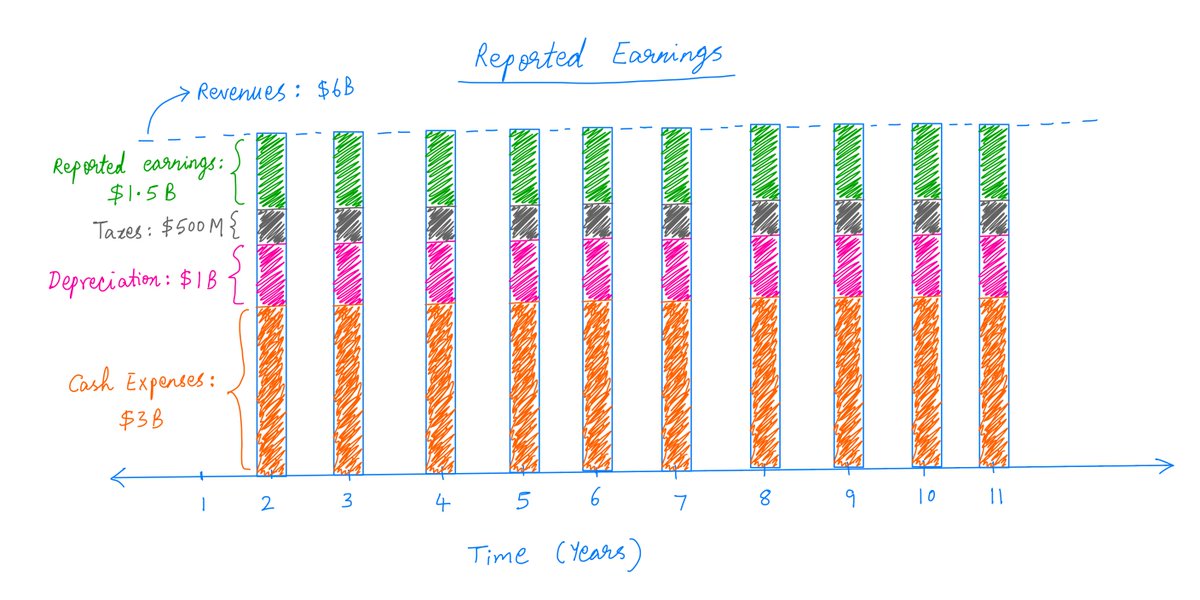

So, each year, for the next 10 years, we have:

$6B in cash inflows,

$3B in cash outflows, and

$1B in depreciation (non-cash) expenses.

Thus, our annual (pre-tax) profit is: $6B - $3B - $1B = $2B.

So, each year, for the next 10 years, we have:

$6B in cash inflows,

$3B in cash outflows, and

$1B in depreciation (non-cash) expenses.

Thus, our annual (pre-tax) profit is: $6B - $3B - $1B = $2B.

21/

Suppose our tax rate is 25%.

Then we pay 25% of $2B = $500M in taxes each year.

This leaves us with $2B - $500M = $1.5B in after tax profits.

This $1.5B is what we& #39;d report to shareholders as net income. So this $1.5B is called "reported earnings".

Suppose our tax rate is 25%.

Then we pay 25% of $2B = $500M in taxes each year.

This leaves us with $2B - $500M = $1.5B in after tax profits.

This $1.5B is what we& #39;d report to shareholders as net income. So this $1.5B is called "reported earnings".

22/

But notice this:

Even though the company only reports *$1.5B* in earnings, it can comfortably pay out *$2.5B* in dividends for 10 straight years (Years 2 through 11).

But notice this:

Even though the company only reports *$1.5B* in earnings, it can comfortably pay out *$2.5B* in dividends for 10 straight years (Years 2 through 11).

23/

Why?

Because, in each of these years, the company has cash inflows of $6B and cash outflows of only $3.5B ($3B operating expenses + $500M taxes).

Dividends are paid from *cash flows*. And in cash flow land, depreciation doesn& #39;t count.

Why?

Because, in each of these years, the company has cash inflows of $6B and cash outflows of only $3.5B ($3B operating expenses + $500M taxes).

Dividends are paid from *cash flows*. And in cash flow land, depreciation doesn& #39;t count.

24/

Suppose the company went ahead and paid out these $2.5B in dividends each year.

Then, from the shareholders& #39; point of view, they put in $10B in Year 1, and got back $2.5B in each of Years 2 through 11.

That& #39;s an annualized return of about 21.4% on their invested capital.

Suppose the company went ahead and paid out these $2.5B in dividends each year.

Then, from the shareholders& #39; point of view, they put in $10B in Year 1, and got back $2.5B in each of Years 2 through 11.

That& #39;s an annualized return of about 21.4% on their invested capital.

25/

Key lesson: Return On Invested Capital depends on the timing of *cash flows* in and out of a business -- not on *reported earnings*. Non-cash accounting adjustments like depreciation can significantly widen the gap between cash flows and reported earnings.

Key lesson: Return On Invested Capital depends on the timing of *cash flows* in and out of a business -- not on *reported earnings*. Non-cash accounting adjustments like depreciation can significantly widen the gap between cash flows and reported earnings.

26/

Lawmakers like to encourage businesses to invest in new projects -- like the $10B invested in our positronic battery factory.

Such investments spur economic activity and create jobs.

To incentivize businesses, lawmakers sometimes allow them to *accelerate* depreciation.

Lawmakers like to encourage businesses to invest in new projects -- like the $10B invested in our positronic battery factory.

Such investments spur economic activity and create jobs.

To incentivize businesses, lawmakers sometimes allow them to *accelerate* depreciation.

27/

Accelerated depreciation means a business deliberately *underestimates* the useful life of its investments.

This "pulls forward" depreciation expenses from the future, which reduces near term earnings and taxes, and hence improves returns on invested capital.

Accelerated depreciation means a business deliberately *underestimates* the useful life of its investments.

This "pulls forward" depreciation expenses from the future, which reduces near term earnings and taxes, and hence improves returns on invested capital.

28/

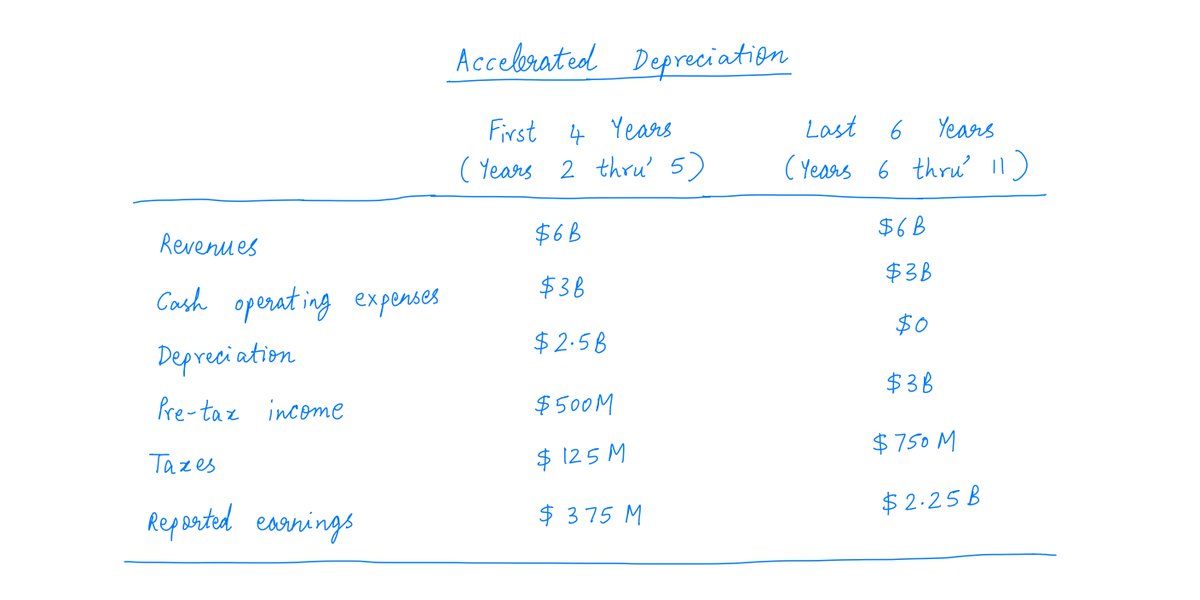

Let& #39;s do an example.

Suppose we deliberately underestimate the useful life of our positronic battery factory. Even though the factory will actually last 10 years, we& #39;ll assume that it will last only 4 years.

Let& #39;s do an example.

Suppose we deliberately underestimate the useful life of our positronic battery factory. Even though the factory will actually last 10 years, we& #39;ll assume that it will last only 4 years.

29/

With this assumption, our depreciation expense is no longer $1B per year for 10 years.

Instead, it& #39;s $2.5B per year for 4 years, and $0 thereafter.

We& #39;ll pay $125M in taxes and report $375M in earnings for 4 years. And $750M taxes, $2.25B earnings thereafter.

With this assumption, our depreciation expense is no longer $1B per year for 10 years.

Instead, it& #39;s $2.5B per year for 4 years, and $0 thereafter.

We& #39;ll pay $125M in taxes and report $375M in earnings for 4 years. And $750M taxes, $2.25B earnings thereafter.

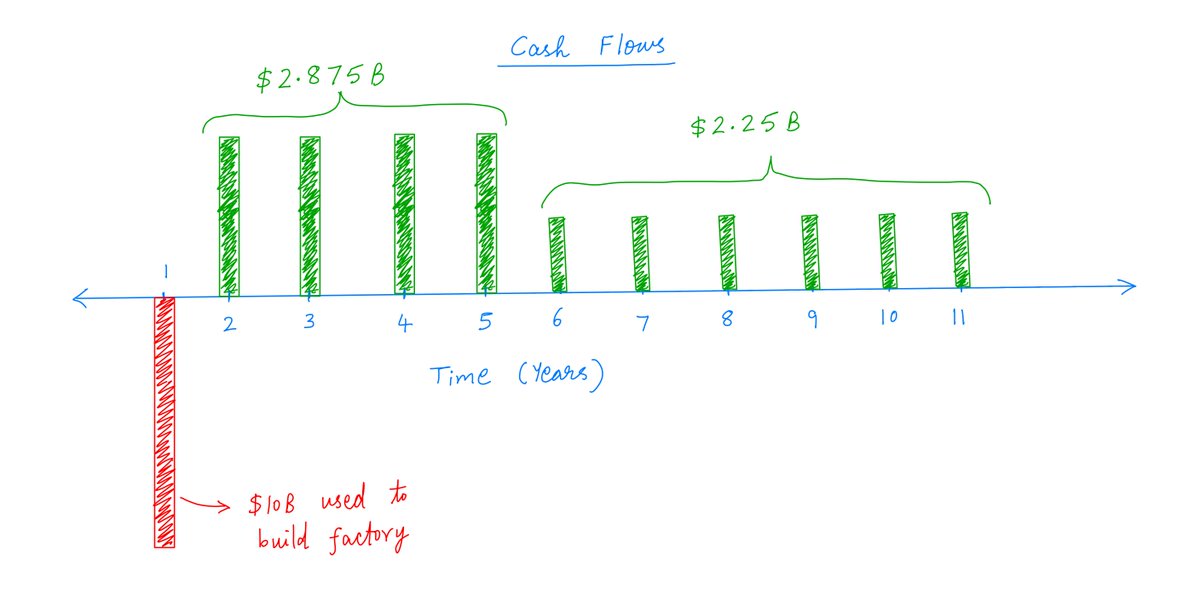

30/

Now, our dividends (reported earnings plus depreciation) can be $2.875B for 4 years and $2.25B thereafter.

This represents a 23.3% return on invested capital -- up from 21.4% when we didn& #39;t accelerate depreciation.

Now, our dividends (reported earnings plus depreciation) can be $2.875B for 4 years and $2.25B thereafter.

This represents a 23.3% return on invested capital -- up from 21.4% when we didn& #39;t accelerate depreciation.

31/

Note:

Over the full 10 year period, total dividends ($25B) and total taxes ($5B) remain the same whether we accelerate depreciation or not.

But with acceleration, dividends are *pulled forward* and taxes are *pushed back*, which improves return on invested capital.

Note:

Over the full 10 year period, total dividends ($25B) and total taxes ($5B) remain the same whether we accelerate depreciation or not.

But with acceleration, dividends are *pulled forward* and taxes are *pushed back*, which improves return on invested capital.

32/

Of course, it& #39;s hard to put a precise figure on the useful life of an asset.

For example, who can say for certain how long a piece of battery making equipment will last?

So, most of the time, depreciation figures have to be "guesstimates". Managements have wide latitude.

Of course, it& #39;s hard to put a precise figure on the useful life of an asset.

For example, who can say for certain how long a piece of battery making equipment will last?

So, most of the time, depreciation figures have to be "guesstimates". Managements have wide latitude.

33/

If management *overestimates* useful lives, we get the *opposite* of accelerated depreciation. This hurts shareholder returns.

But it pulls forward reported earnings. And many management teams are compensated on reported earnings. So there may be a perverse incentive here.

If management *overestimates* useful lives, we get the *opposite* of accelerated depreciation. This hurts shareholder returns.

But it pulls forward reported earnings. And many management teams are compensated on reported earnings. So there may be a perverse incentive here.

34/

Most companies are constantly depreciating some assets, while simultaneously investing capital into other assets.

And reported earnings and cash flows usually consolidate all these depreciation and capital expenses into a single line item.

Most companies are constantly depreciating some assets, while simultaneously investing capital into other assets.

And reported earnings and cash flows usually consolidate all these depreciation and capital expenses into a single line item.

35/

This can make it hard for investors to understand unit economics and thereby infer returns on invested capital.

Reading the "notes to the financial statements" of a company can help here. The notes usually contain information about depreciation schedules and such.

This can make it hard for investors to understand unit economics and thereby infer returns on invested capital.

Reading the "notes to the financial statements" of a company can help here. The notes usually contain information about depreciation schedules and such.

36/

As usual, I& #39;ll leave you with a few references.

In this podcast episode, @ChrisBloomstran beautifully explains the accelerated depreciation provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and how they impact capital allocation decisions at companies: https://moiglobal.com/twiii-s1-e13/ ">https://moiglobal.com/twiii-s1-...

As usual, I& #39;ll leave you with a few references.

In this podcast episode, @ChrisBloomstran beautifully explains the accelerated depreciation provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and how they impact capital allocation decisions at companies: https://moiglobal.com/twiii-s1-e13/ ">https://moiglobal.com/twiii-s1-...

37/

In this episode of Focused Compounding ( @FocusedCompound), Andrew and Geoff discuss in detail the various relationships between the income statement, the cash flow statement, depreciation, and capital expenses: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHYFzrLJAe4">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

In this episode of Focused Compounding ( @FocusedCompound), Andrew and Geoff discuss in detail the various relationships between the income statement, the cash flow statement, depreciation, and capital expenses: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UHYFzrLJAe4">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

38/

This lecture by John Malone also drives home the importance of optimizing depreciation and other expenses to minimize taxes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5QfCLeloEg">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

This lecture by John Malone also drives home the importance of optimizing depreciation and other expenses to minimize taxes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5QfCLeloEg">https://www.youtube.com/watch...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter