For my #CYO2 in #CLST6, I will be talking about Johannes Krause’s lecture titled, “The Genetic History of Plague: On the Doorstep to the Ancient Eastern Mediterranean.”

Johannes Krause is a researcher at the Max-Planck Institute, and he focuses much of his study on pathogens.

Johannes Krause is a researcher at the Max-Planck Institute, and he focuses much of his study on pathogens.

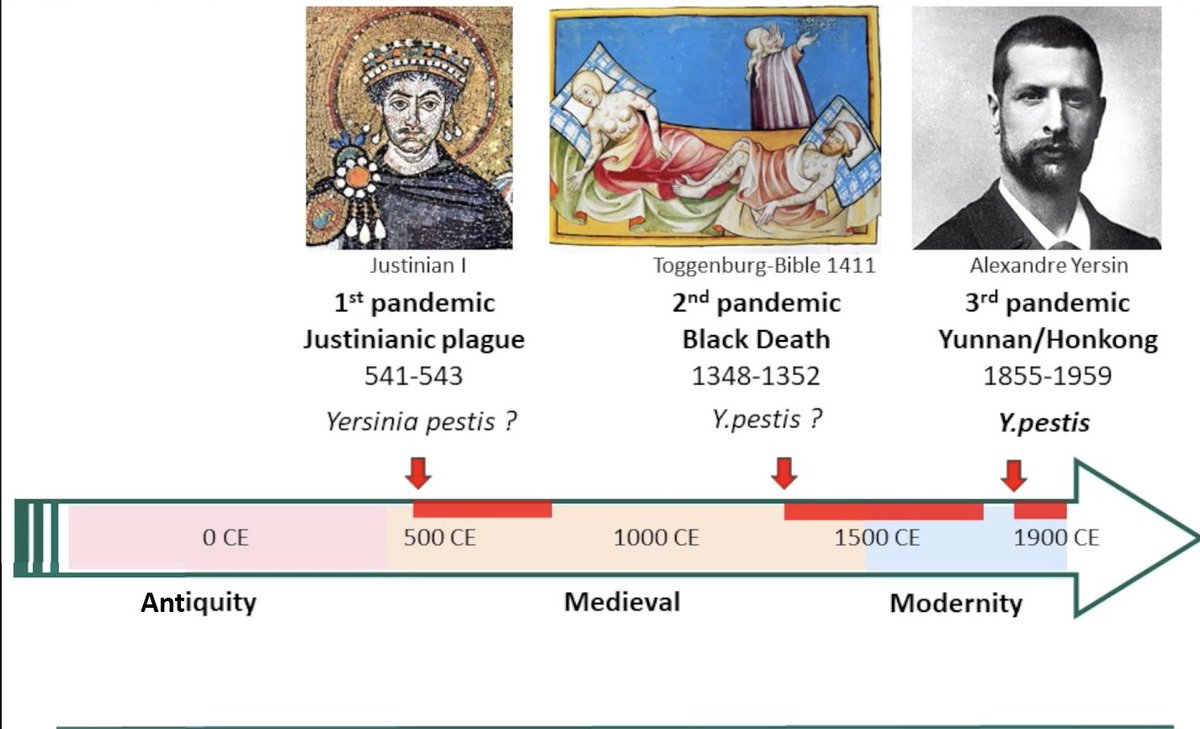

Krause uses many different methods of analysis, one of which includes sequencing genomes of ancient people. One pathogen that he has focused much of his studies on has been Yersinia pestis, which was the cause for multiple pandemics in history (most notably the Black Death).

In this lecture, he covers the history of pathogens and how they developed, then he looks more specifically at the history of Y. pestis and its evolution among humans.

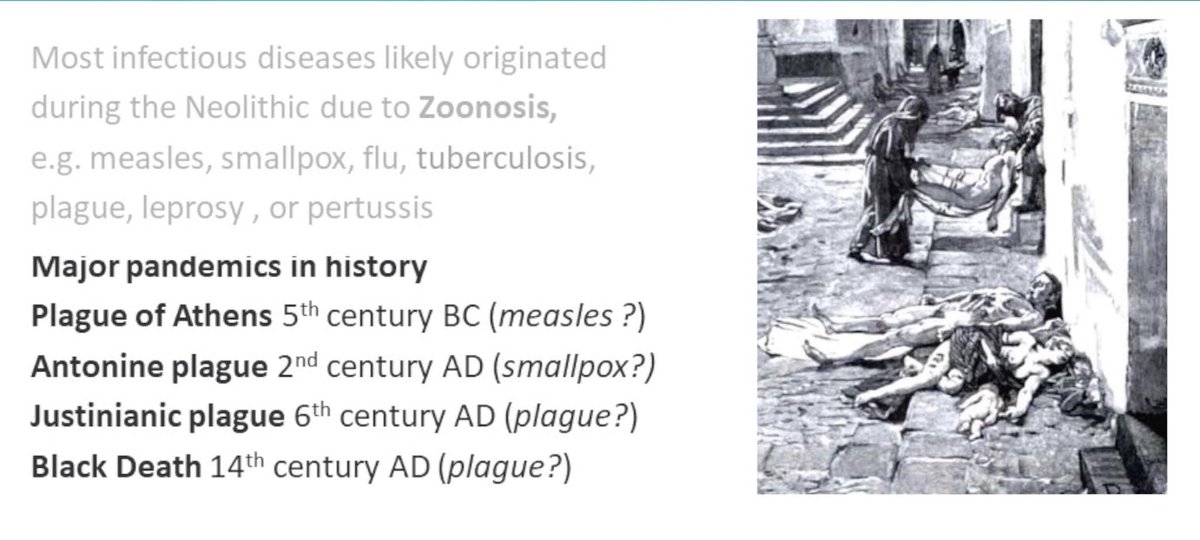

Humans first started encountering dangerous pathogens during the domestication of animals.

Humans first started encountering dangerous pathogens during the domestication of animals.

Many pathogens originate in rodents or bugs, and when humans began sleeping in the same house as cows, dogs, cats, and other domesticated animals the infection rate became much higher. Additionally, with the development of societies, more people lived in densely populated areas.

This would make it easier for the disease to spread because people would be in contact with neighbors and family members at a might higher rate than if they were spread out.

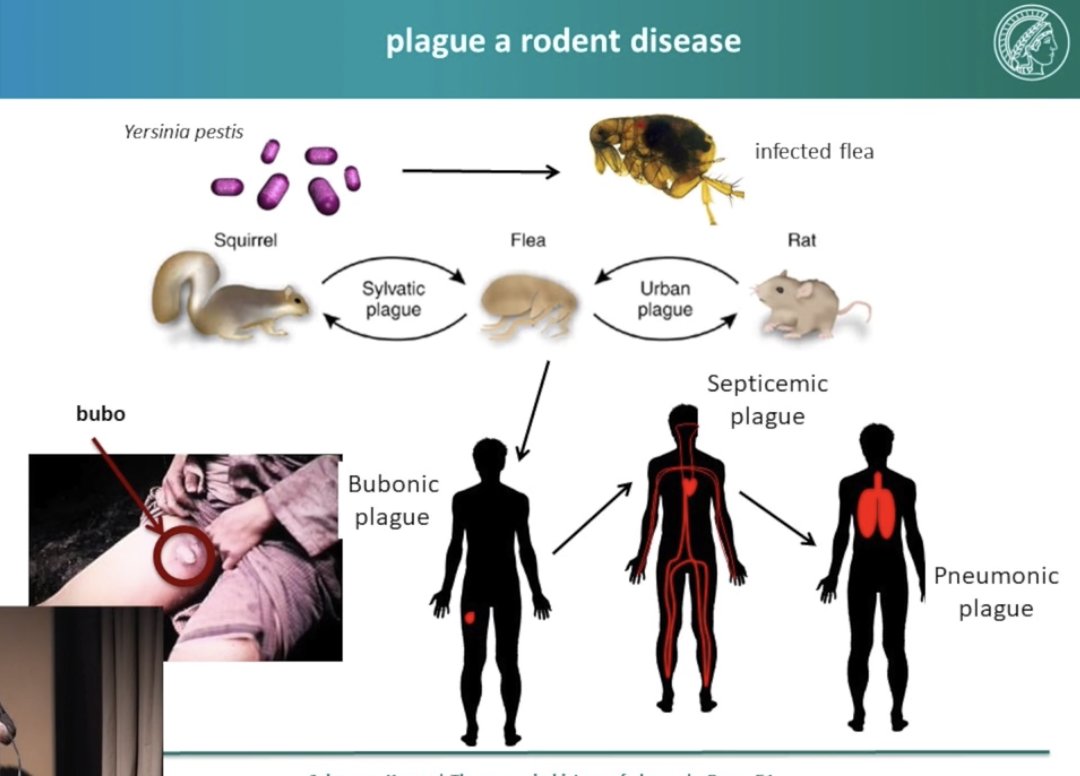

The bubonic plague began because of our close proximity to one another and to rodents.

The bubonic plague began because of our close proximity to one another and to rodents.

Animals such as rats would have fleas on them that were infected with Y. pestis, a bacteria that would propagate within the flea on the rodent until it had killed the rodent and moved the fleas to a new host: a human.

There were three ways that a human could be affected by Y. pestis. One is through the bubonic plague (where the pathogen would travel through the lymph system), another is through a septicemic plague (through the blood), and lastly through a pneumonic plague (through the lungs).

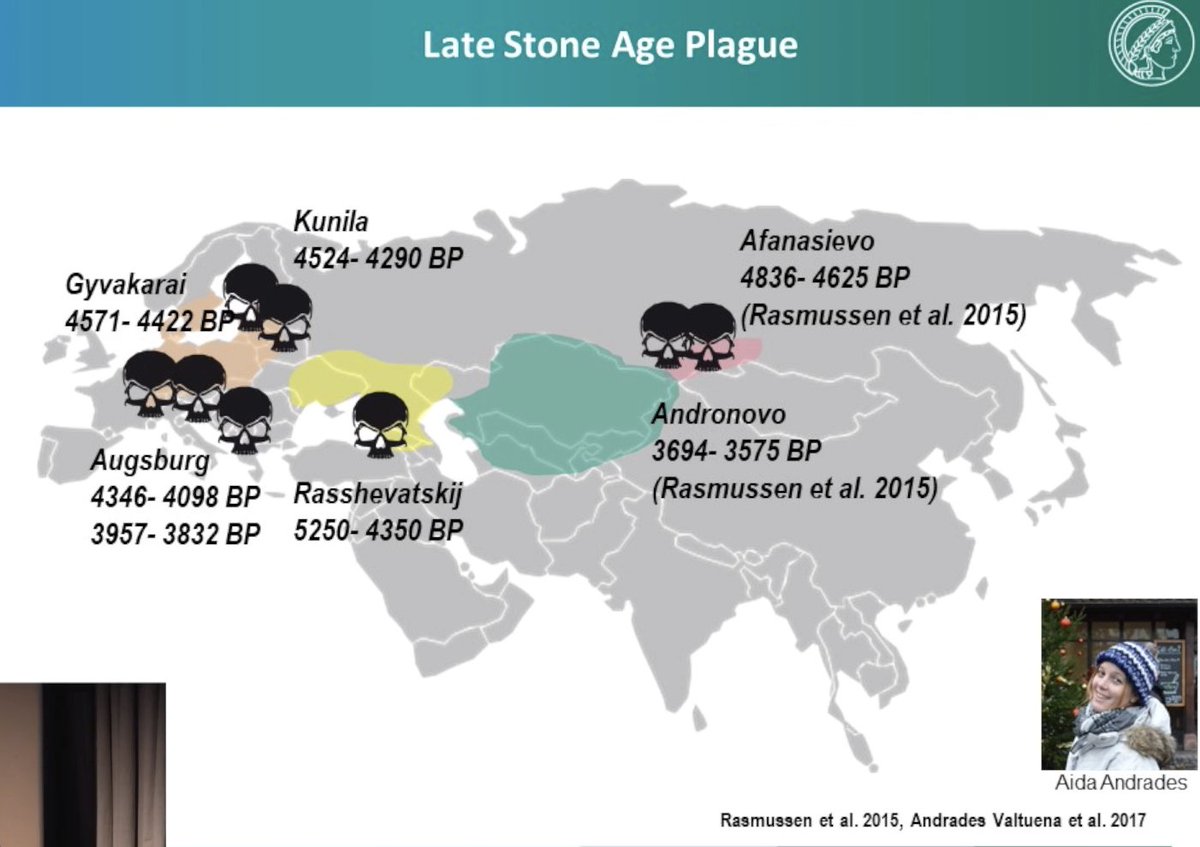

These plagues were thought to have been seen multiple times, but Krause was actually able to use genome sequencing to prove its presence in human history. To do so he would take fragments of teeth from human skulls and try to get DNA samples from any remaining dried blood.

From this, Krause and his team of researchers were able to run the sample through computer programs to see if there was any evidence of Y. pestis. He was able to confirm its presence during the black death, and even as early as the Bronze Age!

This reminds me of our #RR6 focused on bioarchaeology and its wide range of uses ( https://twitter.com/AnnaCLST6/status/1312925999571628032).">https://twitter.com/AnnaCLST6...

This lecture ties into the course more generally because it shows the power of archaeological and bioarcheological evidence in the analysis of human history.

This lecture ties into the course more generally because it shows the power of archaeological and bioarcheological evidence in the analysis of human history.

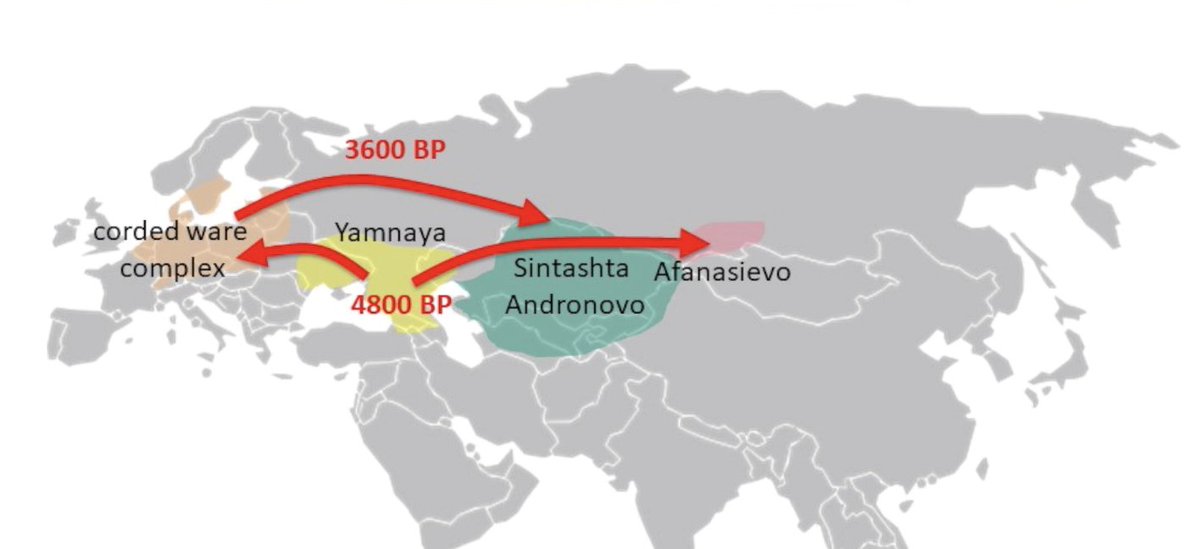

By tracking Y. pestis we are able to learn more about the movements of people and the evolution or downfalls of certain societies. In the course, we aim to use evidence in a similar way to tell a more complete story.

Krause concludes his lecture with a short discussion about the future for bioarchaeology and the potential for new discoveries. Even within his own lab, they have made huge improvements in the efficiency of genome sequencing, and they expect this innovation to continue.

It is interesting to look at this lecture in light of the current pandemic. The COVID pandemic has followed the outline of general pandemics listed in this lecture: starting from an animal, spreading because of the close proximity of humans and globalization.

Hopefully, the results today won& #39;t be as severe as seen in other pandemics in history, but it is important to look to these examples today to understand the vulnerability of the human population against biological threats.

Citations:

The Genetic History of the Plague https://vimeo.com/326994026

RR6https://vimeo.com/326994026... href=" https://twitter.com/AnnaCLST6/status/1312925999571628032">https://twitter.com/AnnaCLST6...

The Genetic History of the Plague https://vimeo.com/326994026

RR6

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter