SCOTUSBlog has posted a nice recap of my argument last week in Pereida v. Barr.

And here& #39;s a thread to honor two people who led, directly and indirectly, to my arguing this immigration case. https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/10/argument-analysis-justices-weigh-mandatory-deportations-based-on-thin-reed-of-minor-crimes/">https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/10/a...

And here& #39;s a thread to honor two people who led, directly and indirectly, to my arguing this immigration case. https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/10/argument-analysis-justices-weigh-mandatory-deportations-based-on-thin-reed-of-minor-crimes/">https://www.scotusblog.com/2020/10/a...

One is my great-grandfather, Philip Goldman, who represents my own family& #39;s immigration story.

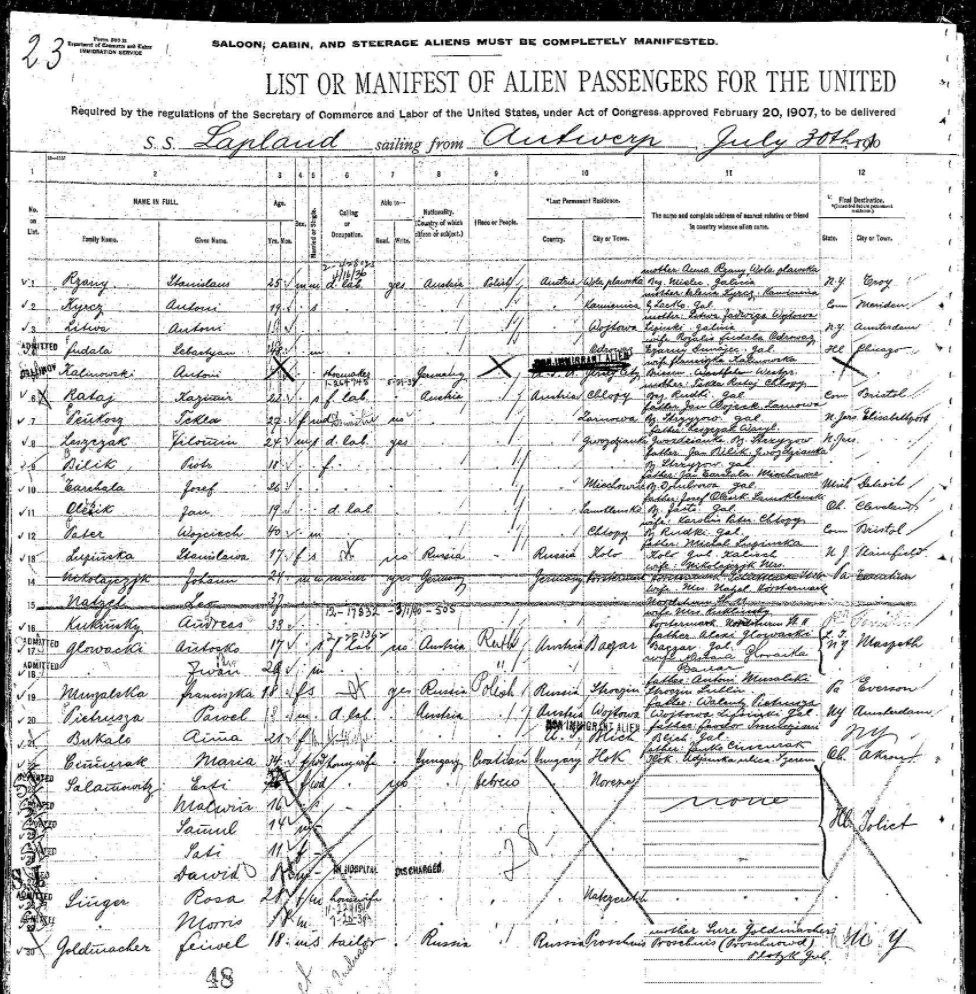

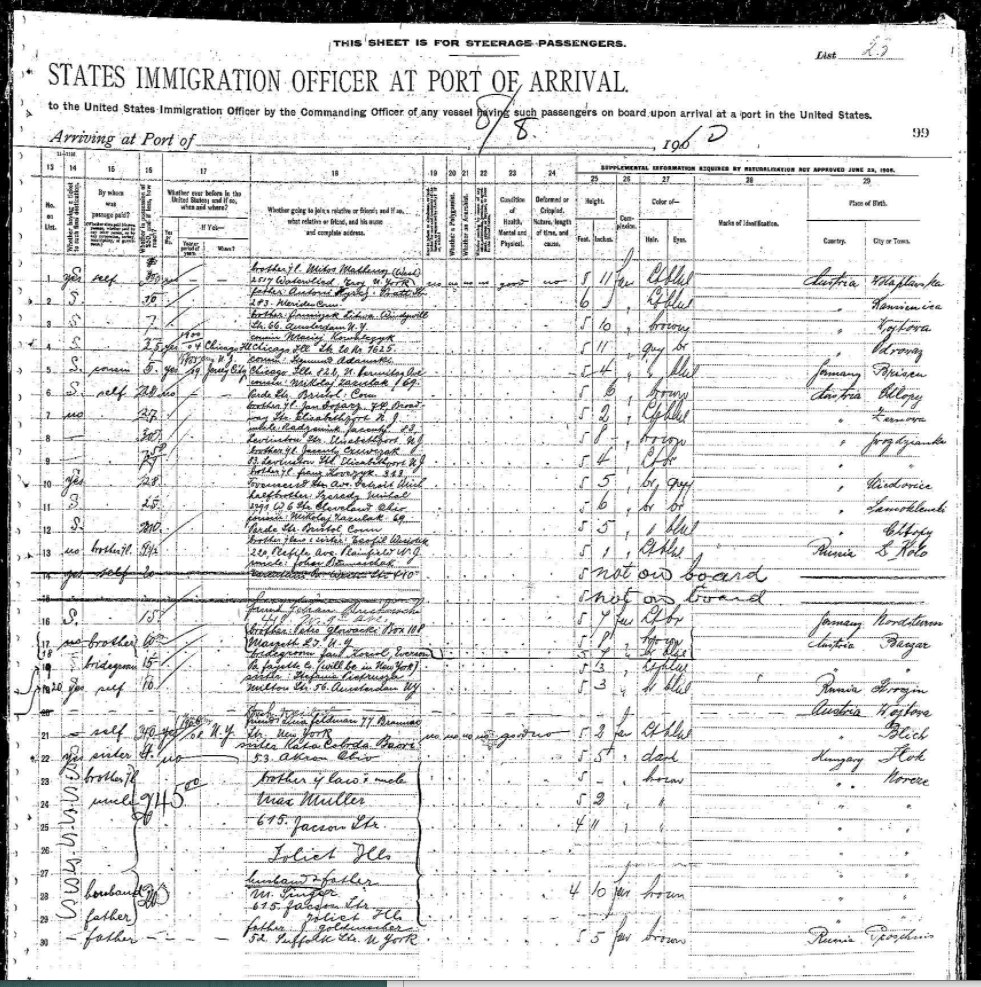

Philip was born Feivel Goldmacher in 1892, in the town of Przasnysz in the Russian Partition of Poland. In 1910, he fled anti-Semitism in the Pale and traveled alone -- at age 18 -- to build a new life in America.

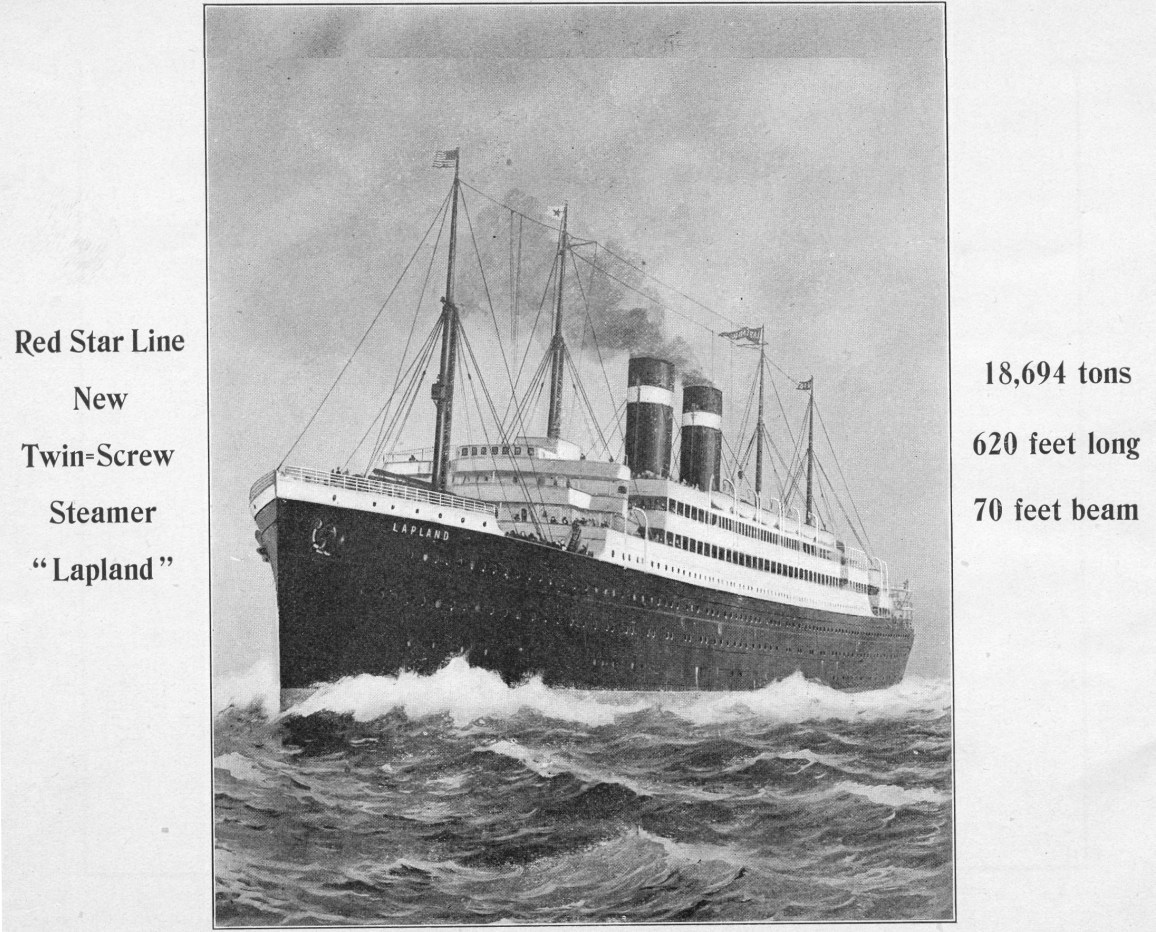

Aboard the SS Lapland, the ship& #39;s surgeon discovered early on that Philip spoke Russian, Polish, German, and Yiddish, and hired him as a translator. So, despite his steerage ticket, Philip made the journey in relative health and comfort in the upper decks.

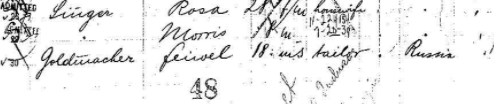

He arrived and was admitted to the United States at Ellis Island on August 8, 1910. One question he was asked at the border was whether he& #39;d ever been convicted of a crime. The Immigration Service Manifest reflects that his answer was no.

Three years later, though, another immigrant arrived in New York and had to answer yes -- he& #39;d been convicted in England of publishing a defamatory libel. His case, US ex rel Mylius v. Uhl, developed what we now call the "categorical approach" -- ...

the rule that courts evaluate the immigration consequences of a past conviction not by investigating the details of old offenses, but instead by asking whether the crime "necessarily" (i.e., by its nature) entailed the kind of criminal conduct that U.S. immigration law targeted.

Now, fast forward 85 years, and my client, Clemente Avelino Pereida, immigrates to the United States from Mexico at age 25 -- slightly older than my great-grandfather was. He too builds a life here, and has a family, including a U.S. citizen son.

But 13 years later, he& #39;s convicted in Nebraska of "attempted criminal impersonation" in connection with allegedly using a fake social security card to get a job to provide for his family.

The government orders him deported, and it says that his conviction strictly bars him from even asking for a form of mercy called "cancellation of removal."

How to analyze his conviction under the categorical approach turns out to be a tricky question that had divided lower courts. So the Supreme Court agrees to take up his case. And, having litigated these issues in the past, @Orrick and I offer to represent him at the Court.

That& #39;s how, 110 years after Philip Goldman arrived at Ellis Island, his great-grandson, Brian Philip Goldman, was arguing in the U.S. Supreme Court about the meaning of Ellis Island-era precedents on behalf of Mr. Pereida.

And staring up at me during the argument were photos of my great-grandfather and of Mr. Pereida. Two men, separated by 80 years, united in their belief in America& #39;s promise as a land of safety and opportunity for them and their posterity.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter