Here, I’ll break down hospitalization data, and explain why we must avoid drawing conclusions or drafting policy based on these data *alone* https://www.axios.com/coronavirus-hospitalizations-increasing-abc7e1f7-51b1-4b5c-a2e8-ab55685ac522.html?utm_campaign=organic&utm_medium=socialshare&utm_source=twitter">https://www.axios.com/coronavir...

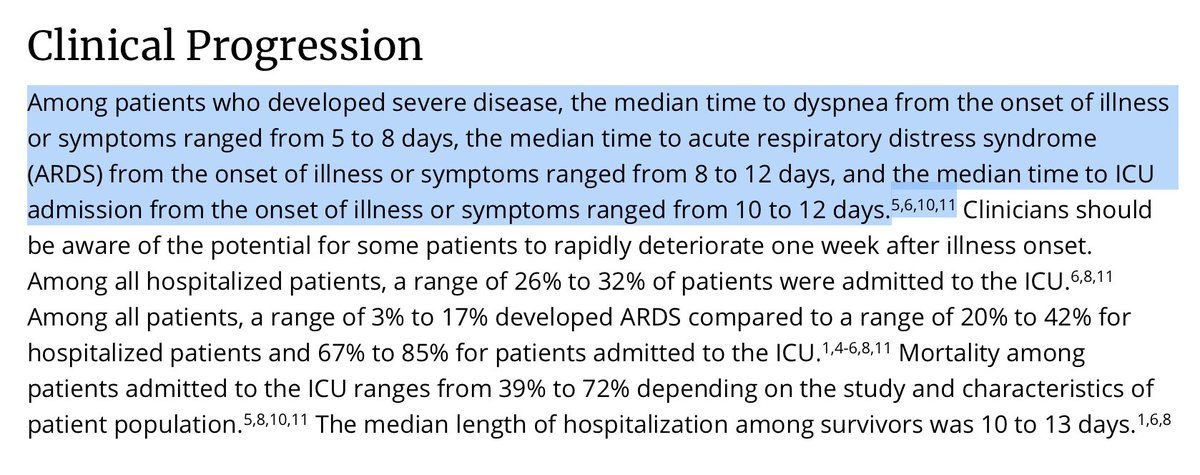

The first thing to note about hospitalization data is that both the numerator and denominator change on a day-to-day basis. Let’s start by looking at the numerator:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Most #COVID19 hospitalizations occur 8 - 12 days after the onset of symptoms

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Most #COVID19 hospitalizations occur 8 - 12 days after the onset of symptoms

src: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html">https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir...

src: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html">https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir...

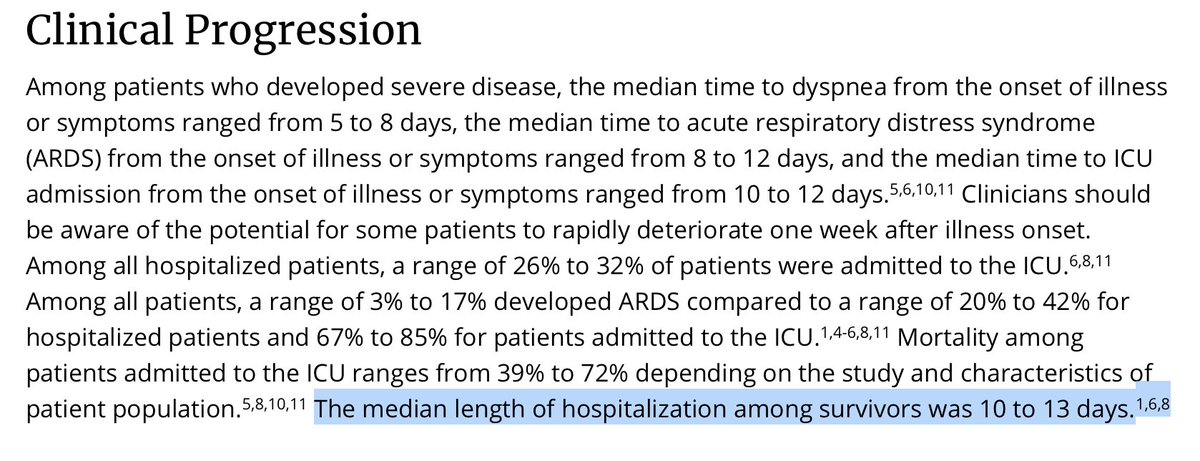

The treatment of COVID-19 has changed over time.

src: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html">https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir...

There are now two treatments that are proven to be helpful in managing #COVID19 in hospitalized patients:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Remdesivir has been shown to reduce the typical (median) amount of time patients spend in the hospital from 15

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Remdesivir has been shown to reduce the typical (median) amount of time patients spend in the hospital from 15  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="➡️" title="Pfeil nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach rechts"> 10 days

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="➡️" title="Pfeil nach rechts" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach rechts"> 10 days

ref: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2007764">https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/...

ref: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2007764">https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/...

ref: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436

ref:

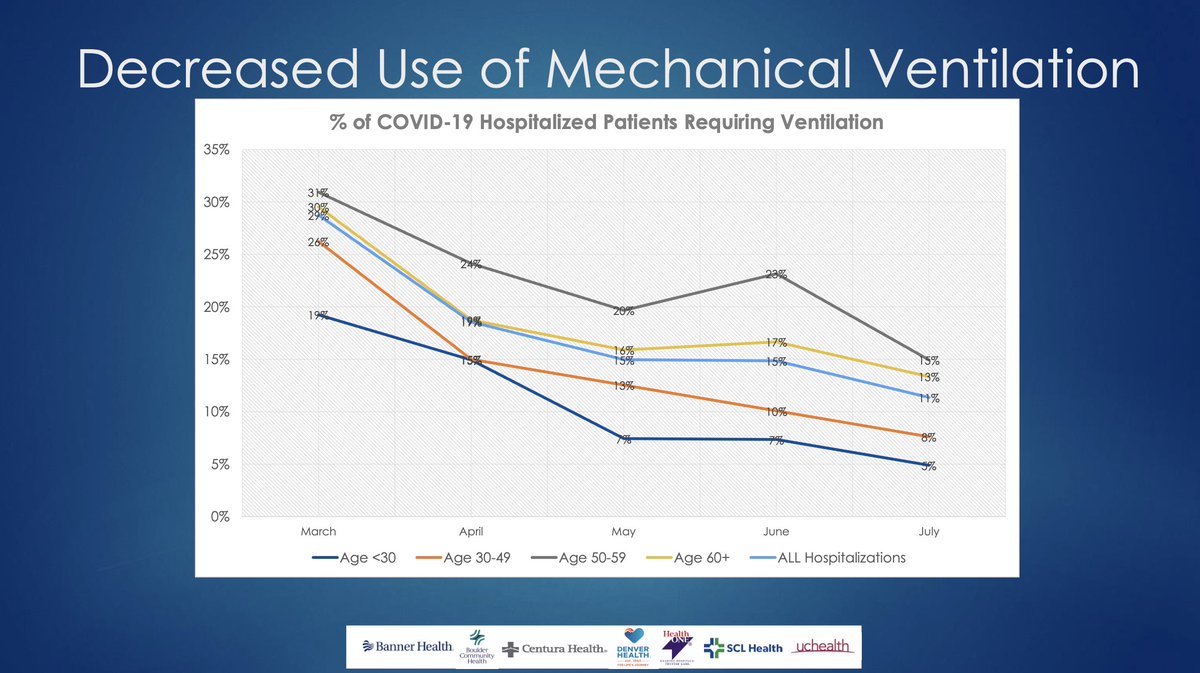

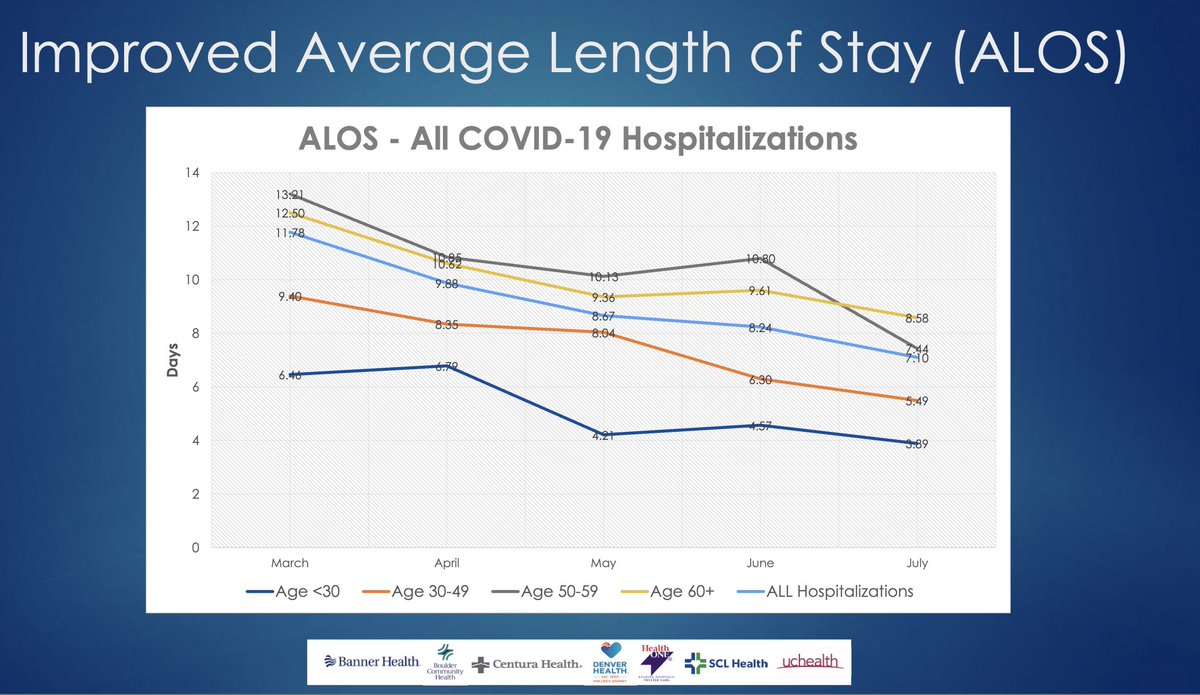

Taken together, we expect #COVID19 hospitalizations to be shorter today, than they were in March through June. And that’s exactly what we’re seeing. In Colorado, for example:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> ventilator use

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> ventilator use

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stay

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stay

H/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/16/new-hospital-data-shows-ventilator-use-fell-over-time-and-coronavirus-patient-stays-grew-shorter/)

src:">https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn

H/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/16/new-hospital-data-shows-ventilator-use-fell-over-time-and-coronavirus-patient-stays-grew-shorter/)

src:">https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn

So, when looking at the number of #COVID19 hospitalizations over time, we must bear in mind that the number of hospitalizations on any given day (numerator) should be lower today, than it was over the summer — *assuming nothing about the disease or the patients has changed.*

I need to step away for a bit, but the upshot so far is:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Shorter #COVID19 hospitalizations translate into fewer people in the hospital for #COVID19 on any given day *so long as community transmission remains the same*

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Shorter #COVID19 hospitalizations translate into fewer people in the hospital for #COVID19 on any given day *so long as community transmission remains the same*

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Scientists have found ways to shorten hospitalizations

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Scientists have found ways to shorten hospitalizations

Shifting gears to the number of hospital beds (the denominator): This value*IS NOT* about bed capacity per se. This value says:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">A physical bed exists

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">A physical bed exists

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">A medical team is available to care for the patient

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">A medical team is available to care for the patient

The number of beds available tells us the number of patients that can be *safely* admitted to the hospital (for any reason)

Similarly the number of ICU beds available tells us the number of patients that can be *safely* admitted to the ICU (for any reason)

Key data is missing..

Similarly the number of ICU beds available tells us the number of patients that can be *safely* admitted to the ICU (for any reason)

Key data is missing..

The # does *not* capture whether:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">the bed is in a unit or ward that can accommodate #COVID19 patients

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">the bed is in a unit or ward that can accommodate #COVID19 patients

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">the *available* staff has the training to safely care for COVID patients

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">the *available* staff has the training to safely care for COVID patients

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">adequate PPE is available

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">adequate PPE is available

These factors https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> *actual* bed available

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> *actual* bed available

CC @meganranney @Cleavon_MD

These factors

CC @meganranney @Cleavon_MD

These factors are most relevant for non-ICU patients, but that’s where “swing” beds come into play— swing beds are one reason why the denominator can change.

There are two definitions of “swing” beds — here we use it to mean regular beds that can be made into “ICU-level” beds.

There are two definitions of “swing” beds — here we use it to mean regular beds that can be made into “ICU-level” beds.

There are also physical beds scattered throughout a hospital that aren’t technically meant to be assigned to a patient that will be staying overnight — like an emergency room.

Taken together, these “extra” beds comprise a hospital’s “surge capacity” — they https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬆️" title="Pfeil nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach oben"> *actual* beds

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬆️" title="Pfeil nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach oben"> *actual* beds

Taken together, these “extra” beds comprise a hospital’s “surge capacity” — they

To recap — there are multiple factors that  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> and

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> and  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬆️" title="Pfeil nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach oben"> *actual* hospital bed capacity. These factors affect every level of care, from the emergency room all the way to the ICU.

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬆️" title="Pfeil nach oben" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach oben"> *actual* hospital bed capacity. These factors affect every level of care, from the emergency room all the way to the ICU.

@TXMedCenter does an exceptional job of breaking down *actual* ICU numbers

see: https://www.tmc.edu/coronavirus-updates/overview-of-tmc-icu-bed-capacity-and-occupancy/">https://www.tmc.edu/coronavir...

@TXMedCenter does an exceptional job of breaking down *actual* ICU numbers

see: https://www.tmc.edu/coronavirus-updates/overview-of-tmc-icu-bed-capacity-and-occupancy/">https://www.tmc.edu/coronavir...

Best I can tell, neither state agencies nor HHS is consistently reporting *actual* #COVID19 bed availability.

When I was still working closely w/ FEMA, they were using @DefinitiveHC’s dataset, but key details are opaque since HHS changed things in July: https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2020-08-03-hhs-updates-covid-19-guidance-and-faqs-hospitals-daily-data-reporting">https://www.aha.org/news/head...

When I was still working closely w/ FEMA, they were using @DefinitiveHC’s dataset, but key details are opaque since HHS changed things in July: https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2020-08-03-hhs-updates-covid-19-guidance-and-faqs-hospitals-daily-data-reporting">https://www.aha.org/news/head...

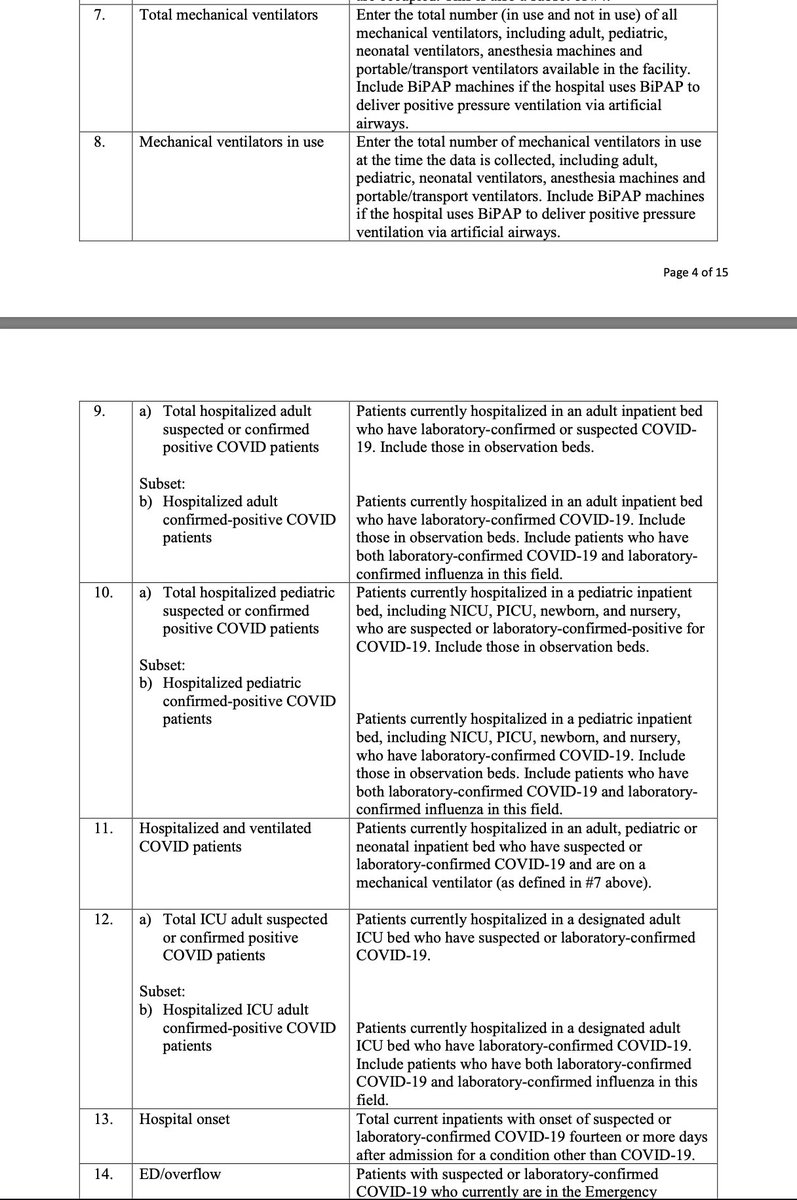

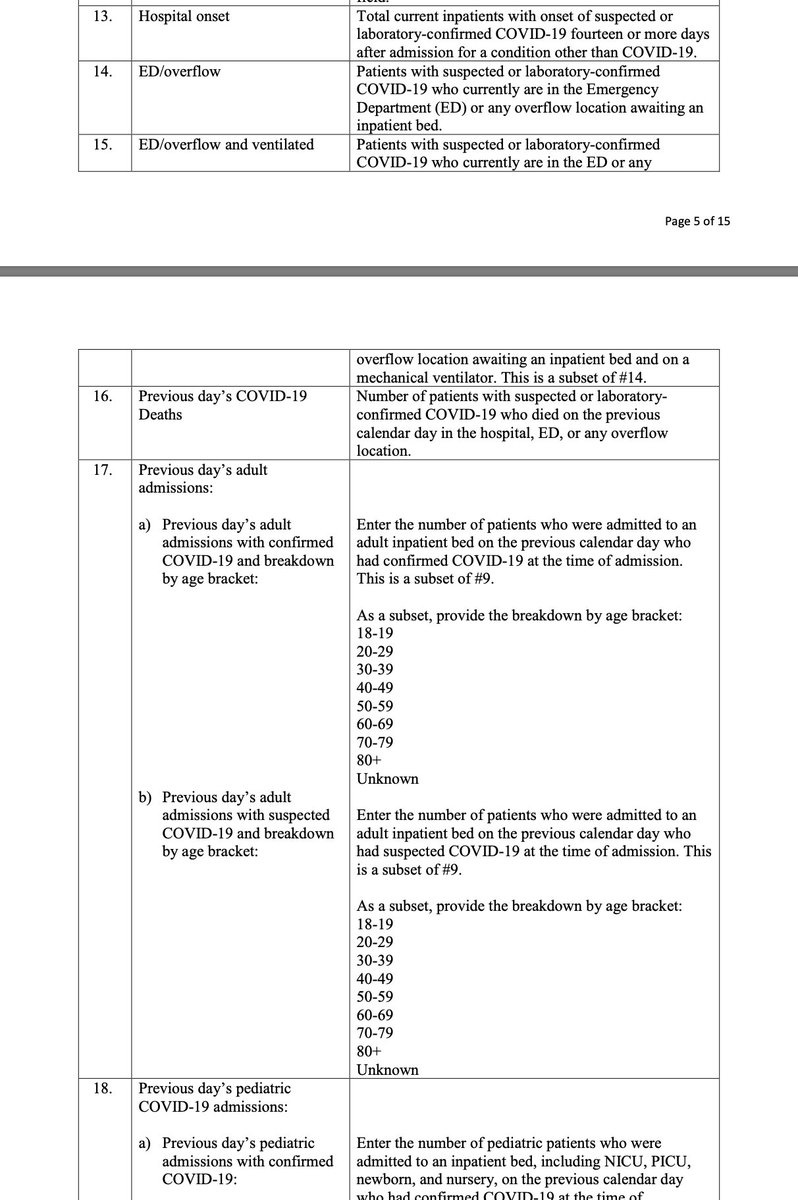

What we *do know* is that hospitals are reporting these key details to HHS via their new system.

We know that based on the guidance document issued by HHS to hospitals: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/covid-19-faqs-hospitals-hospital-laboratory-acute-care-facility-data-reporting.pdf">https://www.hhs.gov/sites/def...

We know that based on the guidance document issued by HHS to hospitals: https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/covid-19-faqs-hospitals-hospital-laboratory-acute-care-facility-data-reporting.pdf">https://www.hhs.gov/sites/def...

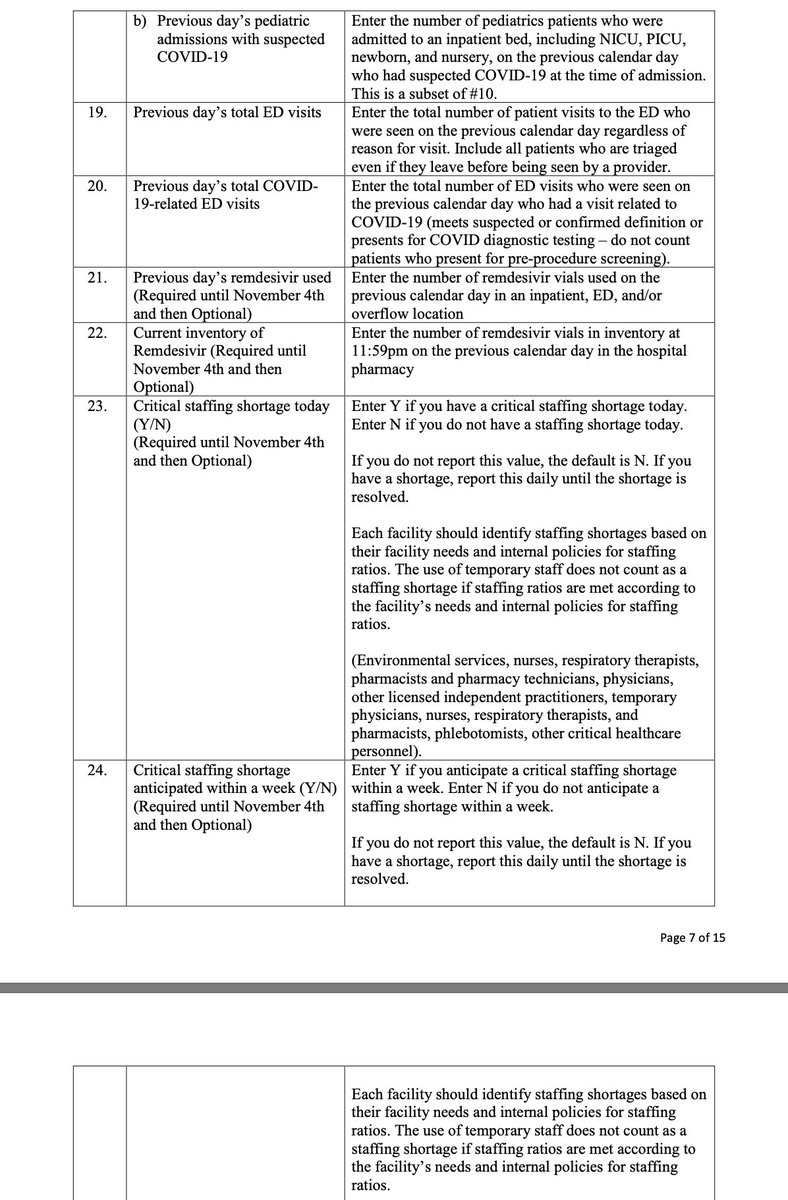

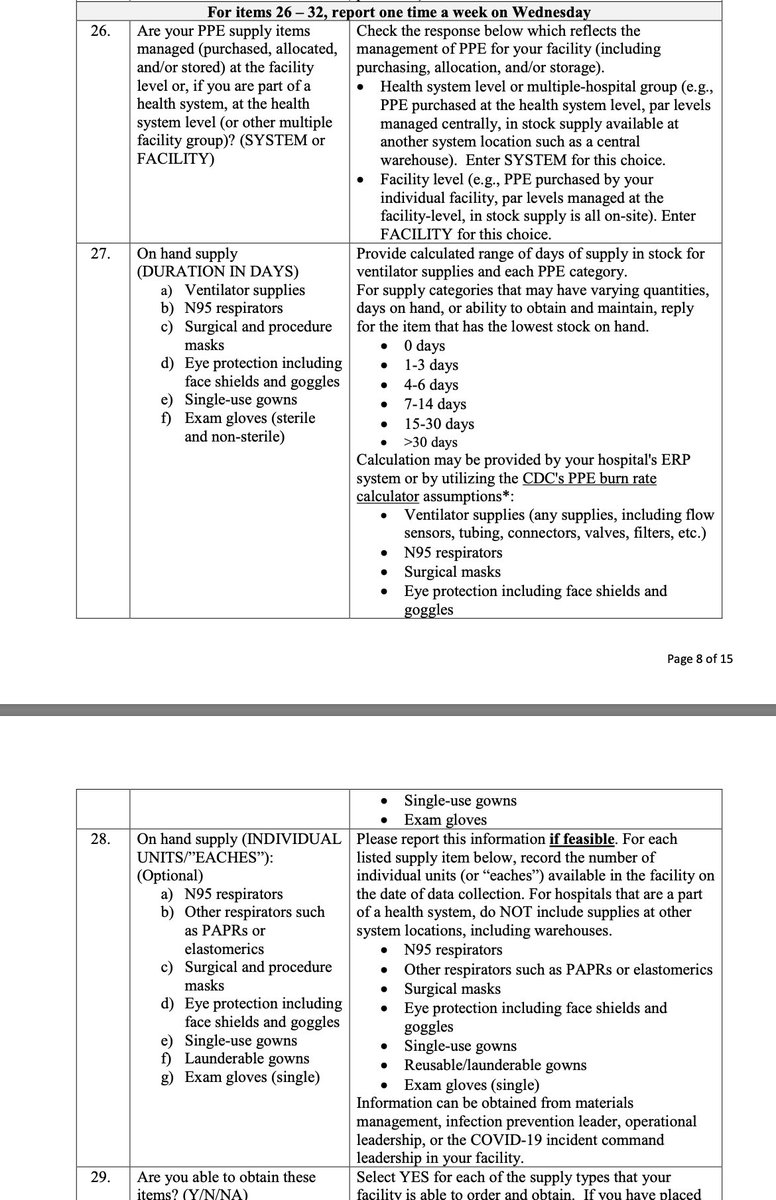

We also know that HHS is collecting information about the availability of PPE on a weekly basis, and the information they collect is remarkably specific — including whether the hospital anticipates a shortage, whether staff reuse PPE, and more.

What we don’t know is what @HHSGov does with that information— and why key details are not made available to the public.

To date, HHS has limited public datasets to an *estimated* hospitalization count at the state level.

https://protect-public.hhs.gov/datasets/state-representative-estimates-for-hospital-utilization">https://protect-public.hhs.gov/datasets/...

To date, HHS has limited public datasets to an *estimated* hospitalization count at the state level.

https://protect-public.hhs.gov/datasets/state-representative-estimates-for-hospital-utilization">https://protect-public.hhs.gov/datasets/...

In summary, drawing conclusions or changing policy based on #COVID19 hospitalization data is fraught with caveats, data gaps, and pitfalls.

We further established that HHS collects the data we need but fails to make that data publicly available…

We further established that HHS collects the data we need but fails to make that data publicly available…

Final thoughts:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">I fail to see why @HHSGov desires to keep the American people in the dark vis à vis real-time hospitalization data (there are easy ways to make the data available without compromising patient privacy)

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">I fail to see why @HHSGov desires to keep the American people in the dark vis à vis real-time hospitalization data (there are easy ways to make the data available without compromising patient privacy)

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">PPE inventories should also be public

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">PPE inventories should also be public

/end

CC @getusppe

/end

CC @getusppe

Examples of why this matters:

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Hospital data transparency sheds light on interdependencies, helps

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Hospital data transparency sheds light on interdependencies, helps  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚩" title="Dreieckige Fahne an einem Pfosten" aria-label="Emoji: Dreieckige Fahne an einem Pfosten"> scarce resources

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🚩" title="Dreieckige Fahne an einem Pfosten" aria-label="Emoji: Dreieckige Fahne an einem Pfosten"> scarce resources

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Right now we’re not getting the full picture, the data can’t tell a complete story

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Right now we’re not getting the full picture, the data can’t tell a complete story

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">By the time we’re aware of a problem, it’s already too late

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">By the time we’re aware of a problem, it’s already too late

H/T @MollyBeck https://twitter.com/wihealthnews/status/1318238701877710848">https://twitter.com/wihealthn...

H/T @MollyBeck https://twitter.com/wihealthnews/status/1318238701877710848">https://twitter.com/wihealthn...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter Most #COVID19 hospitalizations occur 8 - 12 days after the onset of symptomssrc: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." title="The first thing to note about hospitalization data is that both the numerator and denominator change on a day-to-day basis. Let’s start by looking at the numerator:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Most #COVID19 hospitalizations occur 8 - 12 days after the onset of symptomssrc: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

Most #COVID19 hospitalizations occur 8 - 12 days after the onset of symptomssrc: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." title="The first thing to note about hospitalization data is that both the numerator and denominator change on a day-to-day basis. Let’s start by looking at the numerator:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">Most #COVID19 hospitalizations occur 8 - 12 days after the onset of symptomssrc: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

The typical length of stay for hospitalized #COVID19 patients is 10 to 13 days...BUT, this range is based on data from China reported early in the pandemic.The treatment of COVID-19 has changed over time.src: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">The typical length of stay for hospitalized #COVID19 patients is 10 to 13 days...BUT, this range is based on data from China reported early in the pandemic.The treatment of COVID-19 has changed over time.src: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

The typical length of stay for hospitalized #COVID19 patients is 10 to 13 days...BUT, this range is based on data from China reported early in the pandemic.The treatment of COVID-19 has changed over time.src: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." title="https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🔸" title="Kleine orangene Raute" aria-label="Emoji: Kleine orangene Raute">The typical length of stay for hospitalized #COVID19 patients is 10 to 13 days...BUT, this range is based on data from China reported early in the pandemic.The treatment of COVID-19 has changed over time.src: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavir..." class="img-responsive" style="max-width:100%;"/>

ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn" title="Taken together, we expect #COVID19 hospitalizations to be shorter today, than they were in March through June. And that’s exactly what we’re seeing. In Colorado, for example:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn">

ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn" title="Taken together, we expect #COVID19 hospitalizations to be shorter today, than they were in March through June. And that’s exactly what we’re seeing. In Colorado, for example:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn">

ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn" title="Taken together, we expect #COVID19 hospitalizations to be shorter today, than they were in March through June. And that’s exactly what we’re seeing. In Colorado, for example:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn">

ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn" title="Taken together, we expect #COVID19 hospitalizations to be shorter today, than they were in March through June. And that’s exactly what we’re seeing. In Colorado, for example:https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> ventilator usehttps://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⬇️" title="Pfeil nach unten" aria-label="Emoji: Pfeil nach unten"> length of stayH/T @CODaleyNews ( https://www.cpr.org/2020/10/1... @COHospitalAssn">