A question based on what we spoke about on the Science Shambles about brains and mental health yesterday

https://twitter.com/cosmicshambles/status/1318102209867952129

Why">https://twitter.com/cosmicsha... do we (in the west) see mental and physical health as different things?

I can give a 100% definitive answer, but here are some musings

/1 https://twitter.com/NichilessDey/status/1318093165165973505">https://twitter.com/Nichiless...

https://twitter.com/cosmicshambles/status/1318102209867952129

Why">https://twitter.com/cosmicsha... do we (in the west) see mental and physical health as different things?

I can give a 100% definitive answer, but here are some musings

/1 https://twitter.com/NichilessDey/status/1318093165165973505">https://twitter.com/Nichiless...

It& #39;s worth considering that & #39;illness& #39;, & #39;sickness& #39; and & #39;disease& #39; are already slipperier concepts than most people realise. You& #39;d assume we all know what they mean, but look what happens when you check the definitions. Somewhat circular, no?

/2

/2

Predictably, the medical community has worked hard to pin down some proper meaning to terms like illness, sickness etc. Because when you& #39;re dealing with people& #39;s health and intervening in it, you can& #39;t afford to be & #39;vague& #39; in any way

https://mh.bmj.com/content/26/1/9

/3">https://mh.bmj.com/content/2...

https://mh.bmj.com/content/26/1/9

/3">https://mh.bmj.com/content/2...

Even then, it& #39;s tricky. Someone can have a disease, they can be ill, they can be sick. But they need not be all three. diabetes is technically a metabolic disease, but a readily manageable and familiar one, so we rarely think of diabetics as & #39;ill& #39; or & #39;sick& #39;

/4

/4

And who counts as & #39;ill& #39; or not can change over time. Being HIV+ 40 years ago was the worst possible thing for many, health-wise. But with modern treatments, someone who is HIV+ can expect a completely normal physical life (not including stigma etc.)

https://www.medicinenet.com/hiv_treatment_drugs_prognosis_and_prevention/views.htm

/5">https://www.medicinenet.com/hiv_treat...

https://www.medicinenet.com/hiv_treatment_drugs_prognosis_and_prevention/views.htm

/5">https://www.medicinenet.com/hiv_treat...

Point is, treating mental and physical health as separate things is perhaps a consequence of health and illness being inherently slippery concepts in their own right, of people trying to impose some rigidity onto what& #39;s a tricky-to-pin-down issue

/6

/6

However, the way we teach medicine might have had an impact in how we understand mental and physical ailments

A 1989 study showed that the further medical students progress with their training, the broader their definition of disease becomes

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0277953689900774

/7">https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a...

A 1989 study showed that the further medical students progress with their training, the broader their definition of disease becomes

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/0277953689900774

/7">https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a...

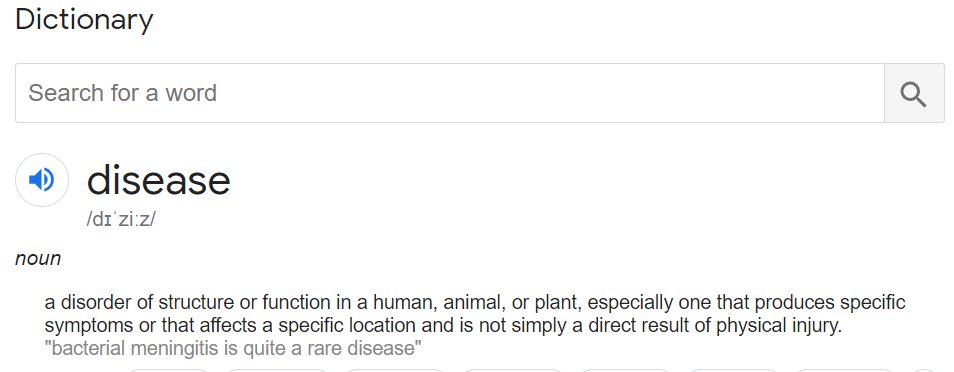

Why& #39;s this important? Well, by most definitions, a disease is something with, typically, a physical basis

"A disorder of structure or function", "Produces specific symptoms", "Specific location", "Not direct result of physical injury"

All suggest tangible, physical origin

/8

"A disorder of structure or function", "Produces specific symptoms", "Specific location", "Not direct result of physical injury"

All suggest tangible, physical origin

/8

But when you deem every illness and ailment to be a disease, it can influence how you deal with them

This has long been cited as an issue with the medical or & #39;disease& #39; model of mental illness; doctors treat mental health patients like they treat physical ailment ones

/9

This has long been cited as an issue with the medical or & #39;disease& #39; model of mental illness; doctors treat mental health patients like they treat physical ailment ones

/9

The fact that doctors/psychiatrists would attempt to tackle mental health problems by addressing the underlying biological issue, while ignoring the psychological/social factors, has been discussed a lot

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137408716_1#:~:text=We%20must%20move%20away%20from,our%20essential%20and%20shared%20humanity.

/10">https://link.springer.com/chapter/1...

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137408716_1#:~:text=We%20must%20move%20away%20from,our%20essential%20and%20shared%20humanity.

/10">https://link.springer.com/chapter/1...

[N.B. Not saying that all doctors/medics still do this now. Far from it. The biospychosocial model has been the default norm in mental healthcare for many years, despite how many known plagiarists claim to have discovered it entirely by themselves]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopsychosocial_model#:~:text=The%20biopsychosocial%20model%20is%20an,disease%20models%20to%20human%20development

/11">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biop...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biopsychosocial_model#:~:text=The%20biopsychosocial%20model%20is%20an,disease%20models%20to%20human%20development

/11">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Biop...

But this means you could argue that the medical field itself adopted and approach where the default idea of illness was physical in nature, something with clear biological origins. And the medical field influences much of our cultural understanding around health, obviously

/12

/12

Unfortunately, as anyone who& #39;s dealt with them will tell you, most mental health problems don& #39;t conform to the same parameters as a more physical ailment

There& #39;s no localised biological cause

Symptoms are far less clearly defined

Treatment options very different

/13

There& #39;s no localised biological cause

Symptoms are far less clearly defined

Treatment options very different

/13

Among other issues, this creates a division between physical disorders, and mental ones. They have different traits, different properties, are dealt with in different ways.

That this would result in classifying/considering them as separate things is likely inevitable

/14

That this would result in classifying/considering them as separate things is likely inevitable

/14

There are also, undeniably, many genuine differences between physical and mental differences

E.g. it& #39;s a lot easier to tell when your body is behaving atypically. If you& #39;re leaking purple slime or your body temp is through the roof, you know that& #39;s wrong, so are unwell

/15

E.g. it& #39;s a lot easier to tell when your body is behaving atypically. If you& #39;re leaking purple slime or your body temp is through the roof, you know that& #39;s wrong, so are unwell

/15

It& #39;s much harder to tell when your mind or psyche is going awry. It doesn& #39;t have a set mass or shape or boundaries or colour, it varies wildly from moment to moment. Clearly determining which of these variations is an & #39;unhealthy& #39; sort is a lot harder to do

/16

/16

There& #39;s also the matter of insight; if you& #39;ve a more physical ailment, your mind is aware of it, because of the pain and discomfort it causes. If it& #39;s a mental ailment, the change is more gradual, less tangible, and affects your mind itself, so objectivity is harder

/17

/17

That physical differences are more accepted and recognised is one potential upshot of all this. It& #39;s also why comparing mental to physical ailments is a helpful tactic when trying to convince people that they& #39;re a legitimate concern

/18

/18

OTOH, there are many ways in which mental and physical ailments do differ considerably, and assuming they& #39;re the same can be honestly harmful, e.g. assuming someone who& #39;s had treatment for a mental health problem is & #39;cured& #39; or & #39;recovered& #39; now

/19

/19

For a thorough understanding of why equating #mentalhealth to physical health problems is potentially harmful, I always point people to @Ladyhaja& #39;s timeless article about this very thing

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jun/30/nothing-like-broken-leg-mental-health-conversation

/20">https://www.theguardian.com/society/2...

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jun/30/nothing-like-broken-leg-mental-health-conversation

/20">https://www.theguardian.com/society/2...

One thing that always bothers me about this mental v physical health division is that it seems to often leads to people assuming you can only have one or the other, that they& #39;re mutually exclusive, for some reason.

This is severely wrong

/21

This is severely wrong

/21

Depression has many physical symptoms, developing a serious physical condition like cancer often leads to depression, and so on.

And then you have neurological disorders, which largely straddle the divide between both camps. And on it goes

/22

And then you have neurological disorders, which largely straddle the divide between both camps. And on it goes

/22

This may be a result of our tendency to consider the brain and body to be distinct entities, like neighbours in a semi-detached house. In actuality, they& #39;re considerably more intertwined. The brain is a bodily organ, after all. The overlap is substantial

/23

/23

As ever, the overall picture is considerably more complex than a basic binary. Sometimes, distinguishing between mental and physical ailments is good and helpful, and other times it& #39;s actively unhelpful

The human form is hypercomplex, but confusing and annoying. Who knew?

/24

The human form is hypercomplex, but confusing and annoying. Who knew?

/24

But then, in our chat yesterday, @helenczerski pointed out that there are some cultures that don& #39;t draw a distinction between physical and mental health, instead considering all health to be the same

Why do we not do that in the Western world?

/25

Why do we not do that in the Western world?

/25

Short answer is, I don& #39;t know. This is clearly a question more for sociologists/anthropologists/historians

But, based on some stuff I& #39;ve gleaned, here& #39;s some speculation on my part, regarding this

/26

But, based on some stuff I& #39;ve gleaned, here& #39;s some speculation on my part, regarding this

/26

Maybe the distinction between mental and physical health is, weirdly, due to The Enlightenment?

https://www.britannica.com/event/Enlightenment-European-history

For">https://www.britannica.com/event/Enl... all the good it did, the emphasis on reason/rationality may have led to a rejection and suspicion of the intangible, i.e. & #39;mental& #39; health problems

/27

https://www.britannica.com/event/Enlightenment-European-history

For">https://www.britannica.com/event/Enl... all the good it did, the emphasis on reason/rationality may have led to a rejection and suspicion of the intangible, i.e. & #39;mental& #39; health problems

/27

This makes some sense when you consider how mental health problems were historically assumed to have religious/spiritual causes, "having visions", "possessed by demons" etc

And see the now-defunct & #39;emotion& #39; Acedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acedia

/28">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aced...

And see the now-defunct & #39;emotion& #39; Acedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acedia

/28">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aced...

While turning against the domination of the church and spiritual concerns in favour embracing logic and reason was, I feel, undoubtedly a good thing, there may have been a & #39;baby with the bathwater& #39; aspect when it comes to mental health problems

/29

/29

A similar thing to this apparently happened in the neuroscience field. Phrenology was widely condemned (rightly), but it led to a hostility to the possibility that different parts of the brain were responsible for different function. But that possibility is 100% right

/30

/30

It& #39;s not a great leap to think something similar could happen with mental health

"Evil spirits that change someone& #39;s thinking and behaviour is nonsense" does not therefore mean "Thinking and behaviour can& #39;t be changed by anything". But it& #39;s no great leap between them

/31

"Evil spirits that change someone& #39;s thinking and behaviour is nonsense" does not therefore mean "Thinking and behaviour can& #39;t be changed by anything". But it& #39;s no great leap between them

/31

Perhaps other cultures, which never went through such a pronounced schism between the spiritual and the tangible, didn& #39;t develop a similar divide between the physical and the mental, and have instead arrived at more & #39;holistic& #39; default assumptions about health?

/32

/32

Not that this is automatically better than our system, of course. As stated, there are pros and cons to treating mental and physical health as separate things

I don& #39;t want to go all & #39;noble savage& #39; here, after all. That& #39;s a whole other issue.

/33

I don& #39;t want to go all & #39;noble savage& #39; here, after all. That& #39;s a whole other issue.

/33

So yeah, that& #39;s my take on the physical v mental health issue

I talk about it a lot more, and in more detail (if you can imagine such a thing) in my book Psycho Logical

Print version out Feb 4th 2021

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Psycho-Logical-Mental-Health-Wrong-Sense/dp/1783352337/ref=sr_1_4?qid=1603052702&refinements=p_27%3ADean+Burnett&s=books&sr=1-4

Audiobook">https://www.amazon.co.uk/Psycho-Lo... out now

https://www.audible.co.uk/pd/Psycho-logical-Audiobook/B07XTN8J38?qid=1568383378&sr=1-3&pf_rd_p=c6e316b8-14da-418d-8f91-b3cad83c5183&pf_rd_r=VB612PT3Q9VQG5FQMA8Z&ref=a_search_c3_lProduct_1_3

/end">https://www.audible.co.uk/pd/Psycho...

I talk about it a lot more, and in more detail (if you can imagine such a thing) in my book Psycho Logical

Print version out Feb 4th 2021

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Psycho-Logical-Mental-Health-Wrong-Sense/dp/1783352337/ref=sr_1_4?qid=1603052702&refinements=p_27%3ADean+Burnett&s=books&sr=1-4

Audiobook">https://www.amazon.co.uk/Psycho-Lo... out now

https://www.audible.co.uk/pd/Psycho-logical-Audiobook/B07XTN8J38?qid=1568383378&sr=1-3&pf_rd_p=c6e316b8-14da-418d-8f91-b3cad83c5183&pf_rd_r=VB612PT3Q9VQG5FQMA8Z&ref=a_search_c3_lProduct_1_3

/end">https://www.audible.co.uk/pd/Psycho...

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter