There are two major Western schools or systems of law: there is the Civil Law system (also known as Roman Law) and the Common Law system (which is English law). What follows is an abbreviated & hopefully clear summary of Roman Law & its impact on the Common Law world.  https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏛️" title="Gebäude im Klassischen Stil" aria-label="Emoji: Gebäude im Klassischen Stil">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🏛️" title="Gebäude im Klassischen Stil" aria-label="Emoji: Gebäude im Klassischen Stil"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⚖️" title="Waage" aria-label="Emoji: Waage">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⚖️" title="Waage" aria-label="Emoji: Waage"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👑" title="Krone" aria-label="Emoji: Krone">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="👑" title="Krone" aria-label="Emoji: Krone"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⚜️" title="Wappen-Lilie" aria-label="Emoji: Wappen-Lilie">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="⚜️" title="Wappen-Lilie" aria-label="Emoji: Wappen-Lilie"> https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🇻🇦" title="Flagge der Vatikanstadt" aria-label="Emoji: Flagge der Vatikanstadt">

https://abs.twimg.com/emoji/v2/... draggable="false" alt="🇻🇦" title="Flagge der Vatikanstadt" aria-label="Emoji: Flagge der Vatikanstadt">

For ease of understanding, and as I am writing in English not Latin, I will describe law using Jus rather “Ius”. I do realise this will upset the purists. Also I am trying to make clear what is a large and complex jurisprudential history.

Put very simply, the Common Law system of law grew up with Britons, then Anglo-Saxons, then Norman, to become English law & this Common Law followed with the English language to the rest of the English speaking world and wherever became or was influenced by the British Empire.

It is true that England was Common Law whereas the Scots had Roman Law & the Irish had Brehon Law but all Celtic domains would be strongly influenced by the English Common Law, such that the British law for the Empire would, for all practical purposes, be the English Common Law.

Simplified, if you speak English every day, then you will generally be living in a Common Law system. This body of law ‘grew up’ from the customary ‘common law’ customs of the English peoples, which grew up over centuries into a body of & #39;common law& #39;. This law was ‘bottom-up’ law.

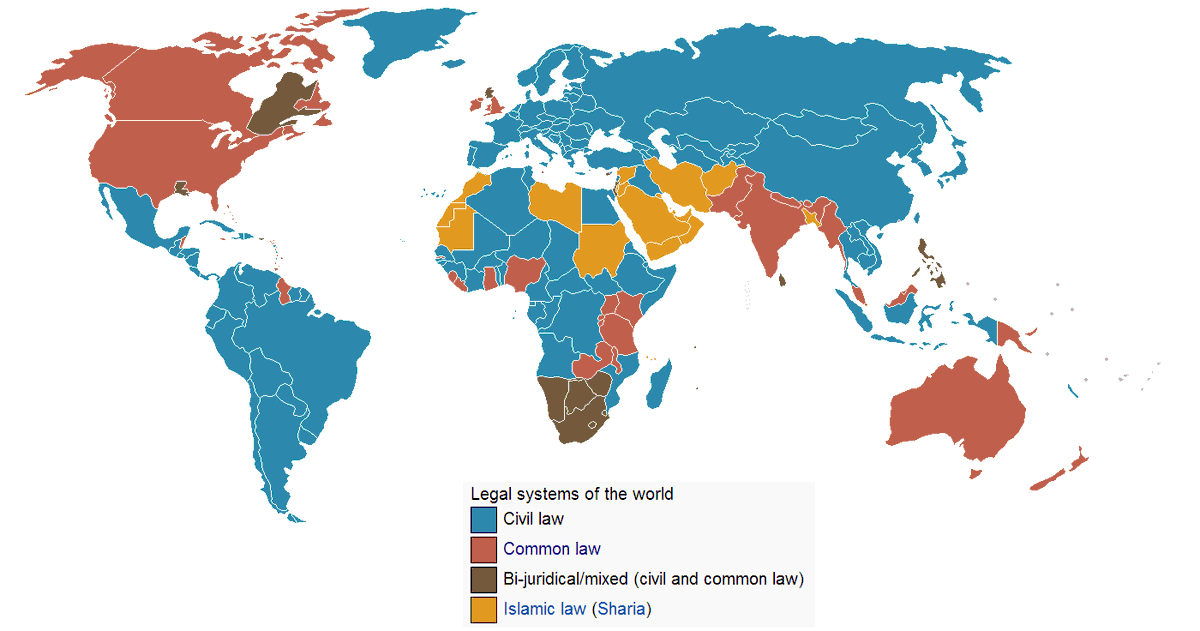

Here is a useful map of the world& #39;s major legal systems FYI.

Roman Law or Civil Law is, instead, more of a system that is ‘top-down’ than is the Common Law system. The law is made or codified into law from & #39;above& #39;. [The growth of Parliaments making general laws as Statutes would alter this in the Common Law world....For another day…]

The Roman concept of Law was, per 2ndC AD jurist Gaius, that Law applied to persons, to things, and to actions. The Romans also believed in different sources of law: Jus Naturale (the natural law), Jus Civile (the law applying to Romans), and the Jus Gentium (the law of nations).

Roman Law was, at first, vague & mainly customary, ie laws derived from pragmatic habit. There were certain cultural norms prevailing throughout Roman society, especially the power of the father over his family & the coercive power of the Roman state over its citizens. #SPQR

Over time, custom was not enough & was abused by the powerful. Roman Law was to be codified into written laws because Plebians demanded to know their exact rights & duties. By 300BC, magistrates had drafted laws that became the Twelve Tables.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelve_Tables">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twel...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twelve_Tables">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Twel...

The Roman Republic’s basic law followed from the Twelve Tables (c450BC) which functioned as a law and a code. The Romans also had “Mos Maiorum”, a set of customary norms for behaviour & conduct that was expected of all Romans by the republican society.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mos_maiorum">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mos_...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mos_maiorum">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mos_...

The Roman law of Aquila was the basic law which concerned remedies for civil wrongs (which are also crimes) such as vandalism, theft etal, and was made in c.290BC - this law would remain good law among the Romans for centuries.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lex_Aquilia">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lex_...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lex_Aquilia">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lex_...

Under the Roman Republic, additional laws were made by assemblies & enforced/adjudicated by Magistrates, particularly the Praetors. Law also grew up from magistrates’ adjudication of these laws and applied in a customary manner.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Praetor ">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prae...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Praetor ">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prae...

As the Roman Republic & then Roman Empire expanded, so, too, did the reach of Roman Law. Roman practice & procedure dominated its world and its law of obligations governed most commercial matters. The power of the Roman State to enforce its Law helped provide needed order

Essential to Roman Law was the idea that law was legitimately authorised and that it was clear, knowable, and binding, on everyone, from Caesar down to the lowliest plebian. It was also law enforced as much by the Roman state’s Magistrate as by the parties or their counsel.

So, for example, in the Bible, Jesus is on trial before Pontius Pilate, as Roman Governor, who questions the (innocent) accused himself as magistrate (John 18:28-40). St Paul as a Roman, appeals to Rome.( Acts 25:9-12). Executive & Judicial power combine in the Roman magistracy.

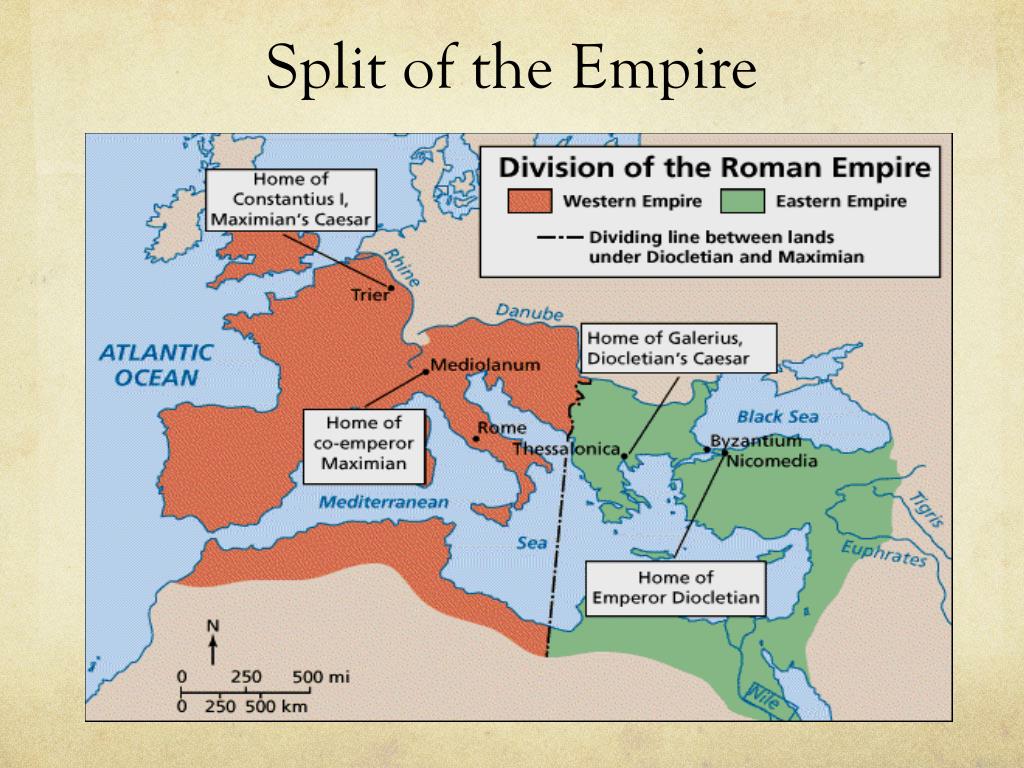

So, the Roman Law or Civil Law system developed from the Roman Republic’s legal system to the Roman Empire, and then came to peak with the greatest Byzantine ruler and lawmaker, the Emperor Justinian (reigned 527-568AD).

The Roman Empire built on much of this Roman republican legal settlement. The later influence of Christianity would develop, further, Roman law, such that by Justinian’s time, the Roman legal world had bases in not just Roman republican norms but Biblical ones as well.

Important here to note that after the Roman Republic came by the 1stC AD the formalised Roman Empire - and that this Roman Empire split into East & West in c330. The Western empire collapsed 476AD. The Eastern Roman/Byzantine Empire kept going to 1453 when Constantinople fell.

Over time, the Roman Law had become increasingly messy and confused, with the Jus Civile nominally governing Romans having expanded well beyond the Twelve Tables to include all manner of legislation, various Emperor’s codes, Magistrates precedents, and eminent jurists’ writings.

In approx 530, Emperor Justinian now presiding over the eastern Byzantine Empire wanted to bring order to Rome’s laws. He and his jurists would over the next decade create the Corpus Juris Civilis or the Body of Civil Law. It would found much of European law up to our times.

The Corpus Juris Civilis or the Body of Civil Law of Justinian& #39;s time contained 3 major parts:

-the Digest of the law& #39;s writings

-the Institutes of the law

-the Justinian Code (the Codex Justiniani)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corpus_Juris_Civilis">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corp...

-the Digest of the law& #39;s writings

-the Institutes of the law

-the Justinian Code (the Codex Justiniani)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corpus_Juris_Civilis">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corp...

The Digest (c533) compiled all Rome’s historic legal texts brought together in one book. In order to prevent errors and contradictions of the Digest, Justinian apparently ordered his jurists to destroy all other Roman law texts that could be found.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digest_(Roman_law)">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dige...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digest_(Roman_law)">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dige...

The Institutes of Justinian were akin to a guide or explainer of Roman law as it applied to people, things & acts, based largely on the work of Gaius, a Roman jurist of the 2ndC BC. However, unlike most textbooks, the Institutes had legal force.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institutes_of_Justinian">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inst...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Institutes_of_Justinian">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inst...

The Justinian Code (c534AD) was the Empire’s codified law on public & private law subjects that bound everyone. The Code was the result of Justinian’s juridical commission compacting all the various imperial constitutions & laws into one comprehensive code

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Justinian">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code_of_Justinian">https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Code...

Roman Law, thus, from its humble beginnings in the centuries BC up to Justinian in the 6thC AD, became this comprehensive legal system. Its influence would be felt throughout Europe & wherever European law went. Roman Law was relied on by Church, Kingdom, Republics, markets etal

Even in England, the Roman or Civil Law would be taught at the growing Oxford University. What made England different however was its Royal Courts & the Inns of Court from which lawyers practised, and whose judges & counsel would develop precedents in the absence of codified law

Among the biggest legacies of Roman Law, even in common law jurisdictions, are the ideas & ideals of codified laws:

- laws are to be made & enacted by legitimate authorities in a form that is clear & cohesive

- laws are to be knowable to all

- laws bind the Ruler and the Ruled

- laws are to be made & enacted by legitimate authorities in a form that is clear & cohesive

- laws are to be knowable to all

- laws bind the Ruler and the Ruled

In practical terms, the Roman ideal of a clear and codified law meant that the law was to be applied as it is exactly expressed, with an emphasis by the Magistrate or Judge on applying that law to the precise facts of the individual case, with less of a role for precedent.

The Common Law world, esp as Britain had and still does not have a completely written constitution, developed, instead, a concept of ‘stare decisis’, of a binding respect for higher courts’ precedent as a source of law, as a way of imposing uniformity on lower courts & law itself

The advent of written Constitutions as the fundamental law for a polity was/is the ultimate Roman Law triumph over the Common Law: the polity& #39;s basic law, binding on all persons within its realm, expressed in clear terms, and which ‘constitutes’ the State & its government.

Under a written Constitution, this fundamental law and its text is the super-precedent that binds everyone, especially courts and judges. Individual cases & appeals are determined by judges who apply the Constitution’s precise text to the facts of each case, ie not stare decisis

The problems faced in the US & the UK, and to a blessedly much lesser extent in Australia, is that of active Common Law judiciaries trying to develop precedent, when the written Constitution as basic law is the only legitimate precedent & indeed the only source of judicial power.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter