When people ask "when did people stop speaking Latin as a native language?" I like to answer: “Well, it was still spoken into the 9th century, though at that point spoken Latin had become pretty different from the written language.”

(Thread...)

(Thread...)

The right question is not "when did people stop speaking the Latin language?"

It& #39;s "when did they start believing that the language they spoke wasn& #39;t Latin?"

And the answer to that is: not until pretty damn late.

It& #39;s "when did they start believing that the language they spoke wasn& #39;t Latin?"

And the answer to that is: not until pretty damn late.

People from Gaul, Italy and Iberia are still described as native speakers of Latin throughout the Early Middle Ages. Latin took a long time to become a conceptually "different language" from Romance.

As late as the 8th century Paul the Deacon mentions Bulgars settled in Italy who "although they spoke Latin, hadn& #39;t lost their own original language" (qui usque hodie ut in his diximus locis habitantes, quamquam et Latine loquantur, linquae tamen propriae usum minime amiserunt.)

There is no question of Bulgars like these learning the Bookish Latin in which Paul is writing. The Latin they spoke was in fact the vernacular of the area they had settled in.

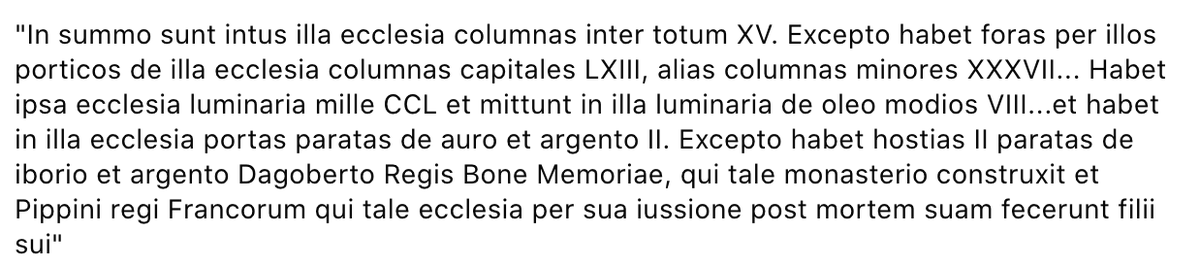

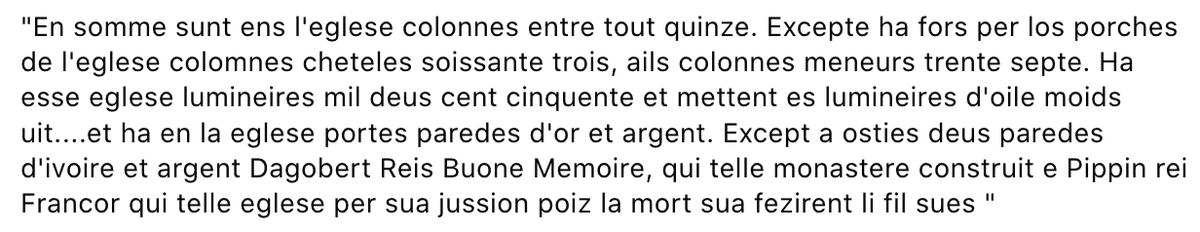

Vernacular utterances when put into writing before the 9th century took on a latinate appearance. There are Latin texts that are pretty clearly straight-up written vernacular. For example, a description dated to 799 of the Basilique de Saint-Denis:

This can be easily read essentially as "Archaic Old French" mostly just by knowing the complicated grapheme-to-phoneme correspondences.

The Latin/Romance conceptual split apparently happened at different rates in different regions — much earlier in Gaul than in Hispania. And it probably took a long time to filter down the social scale from the elite to illiterate peasants

(ideas of separate languageness, to my knowledge, always begin at the top of the social and educational scale.)

But for the most part, the beginning of the process seems to coincide fairly precisely with the decline and eventual break-up of the Carolingian Empire in the late 9th century, and the fragmentation of its successors. I personally don& #39;t think that this is a coincidence.

Here& #39;s a useful way to think about Latin in the early Middle Ages, back when Romance was still seen as a spoken version of it. The dialect continuum of "German" from Alemannic to Hessian to Low Saxon stretches far beyond mutual intelligibility....

But the Germanic spoken across the border in the Netherlands is "Dutch" and not "German" even though it is in many ways a further extension of that same continuum. That border separating them is an arbitrary concept with real linguistic ramifications.

It matters because speakers believe and behave like it does, in language as much as anything. Learning to speak both Low Saxon and Alemannic may require as much work as learning to speak both Italian and Portuguese, but not the belief that these are two different languages.

In fact, one need not believe that Italian and Portuguese are different languages either, for that matter. That we all agree that they are is an arbitrary consensus brought about by non-linguistic cultural and political factors.

Now it is by now a point of wearisome banality that the difference between a dialect and a related language is a matter not of linguistic desiderata but of social and cultural attitudes.

What they speak in my village, what they speak in the village three valleys away, and what they speak all the way on the other end of the island, may be three languages or three versions of one language, depending on how we all agree to think of it.

Here& #39;s the kicker: this principle applies not only horizontally across space, but vertically within the society, to the difference between what I speak to my kids, what I speak at court, what I dictate letters to the Bishop in, and what I pray in.

No matter how syntactically, lexically, morphologically or typologically different two related varieties may be from each other, they may in principle still be perceived, treated and functionally used as no more than two opposite "registers" or "styles" of a single language.

All that is required is a fluid continuum between the two extremes, analogous to a dialect continuum, but existing all within a single speaker.

Existing, that is, as a gradation of stylistic possibilities among which the speaker feels able to move, depending on context, without ever crossing into what they feel to be a different language.

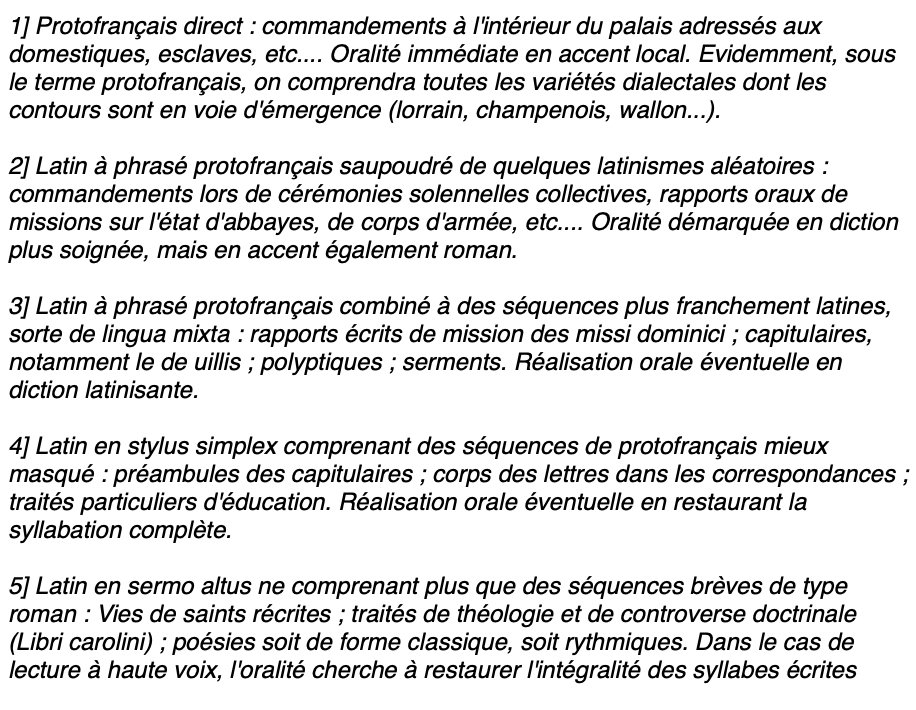

Michel Banniard, in his illuminating discussion of Early Carolingian Latin, describes 5 different levels

Banniard probably doesn& #39;t know it, but the gradation he sets up is reminiscent of the five levels of language set up by El-Said Badawi to describe the sociolinguistic situation in 20th century Egypt.

Banniard& #39;s levels 1-2 correspond mostly to Badawi& #39;s 2-3, and Banniard& #39;s 3-5 correspond to Badawi& #39;s levels 4-5.

The parallels are not exact. Nor would one expect them to be. Badawi& #39;s level 1, the unmediated colloquial speech of illiterates (which is not the same as the speech of literates addressing illiterates, or of illiterates as relayed by literates) is inaccessable to Banniard.

Badawi had the luxury of describing a living contemporary language with speakers who could be observed, including illiterates. With Early Medieval Latin we are confined to whatever texts happened to survive, and it is a bit hard for illiterate people to write.

But the parallels are real and not a coincidence.

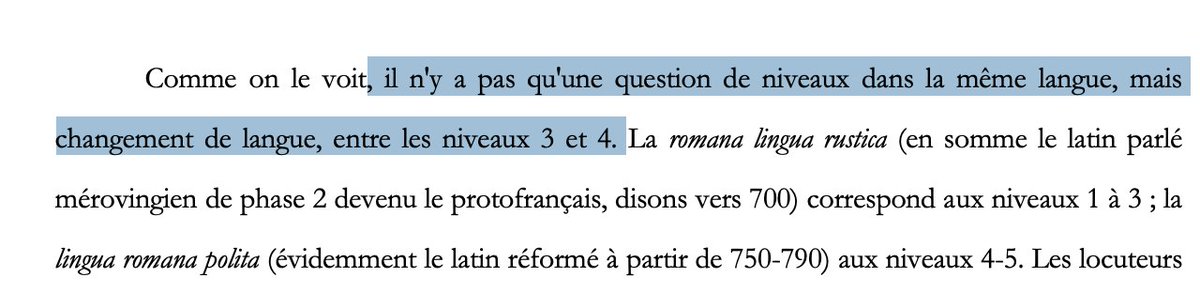

Banniard quite unacceptably follows his insight by saying that this was not actually a matter of levels within a single language, but a change of language between levels 3 and 4.

At the same time, on the same page, he admits that the educated were aware of no such linguistic boundary.

But it was not merely "les plus éduqués" who did not perceive common speech as a language other than Latin. No writer of any education level in the 7th-9th centuries gives any indication that they thought the masses spoke something that was not Latin.

Traditional Latinists, Romanists and medievalists spent aa long time getting very accustomed to thinking of Romance and Early Medieval Latin as different languages.

Just as they are to thinking of the Romance of the 10th-12th centuries as a group of related languages rather than divergent dialects.

Later history has so affected our thinking that it is still often difficult for philologists to conceive of it in terms other than those we have inherited from the nationalistic 19th and 20th centuries.

Even when the seamless sociolinguistic gradations between "Latin" and "Romance" in the Early Middle Ages are acknowledged, modern habits kick in so automatically, it is hard to really see the language for what it was to its own speakers, writers & learners, in its own time.

Read on Twitter

Read on Twitter